Emilio Prini: …E Prini, installation view, MACRO, Museo of Contemporary Art of Rome, 27 October 2023 – 31 March 2024. Photo: Melania Dalle Grave, DSL Studio.

Macro, Rome

27 October 2023 – 31 March 2024

by JOE LLOYD

One hot summer day in 1989, Emilio Prini (1943-2016) entered Studio Ghiglione in Genoa carried in a sedan chair. Photographs show the artist largely hidden from view behind a curtain. In those that do capture his bearded face and torso, he seems to be giving the finger to his captor. Prini was in the chair because he had vowed never to set foot on Genovese soil again. To ensure he met his vow even if he had to leave the chair, he had arranged for the gallery floor to be covered in cellophane. Interlocutors asked him questions, to which he responded by pointing to various inscriptions on the wall and floor. After the event, he was carried to a ferry that sailed out into the sea.

Photographic documentation of the intervention carried out for the exhibition Op losse schroeven: Situaties en Cryptostructuren, Amsterdam, 1969. Courtesy Archivio Emilio Prini.

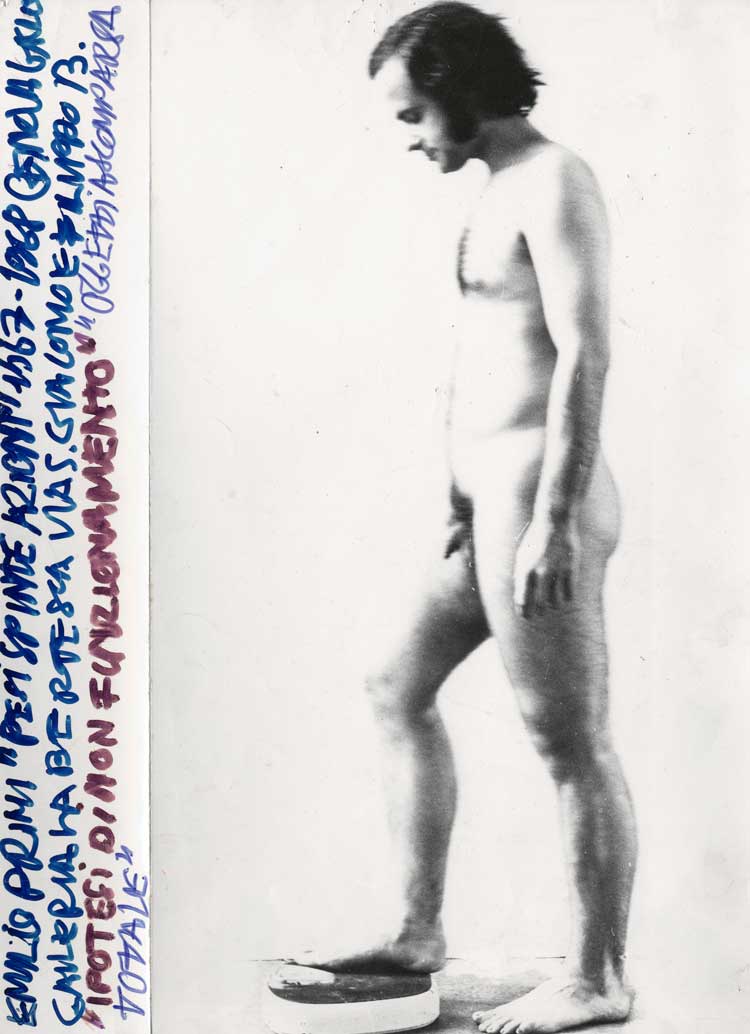

I am not sure if Prini kept his vow, but it would not surprise me if he did. He turned his whole life into a strange sort of performance. The most mundane scenes could be repurposed for art. One 1968 photograph depicts him naked, one foot on a weighing scale. Prini was a prominent figure in the arte povera movement, which revolutionised Italian art. But his work stands slightly apart from that of many of his better-known compatriots. Regal Turin was the movement’s capital. Prini’s practice instead fermented in Genoa, a salty port city of winding medieval alleys hemmed in by hills. And while his contemporaries created works with a startling visual clarity, Prini’s oeuvre is a maze of traces and fragments that the audience have to activate for themselves.

Project of the poster created by the artist for the exhibition Pesi spurteazioni, Galleria La Bertesca, 1967-1968. Courtesy Archivio Emilio Prini.

Macro’s Prini retrospective is elephantine, with 243 separate works, some of which contain multiple elements. But not all of them are stand-alone opuses. Many of Prini’s artworks are small and text based. He once declared: “I create nothing, if possible.” And you might mistake them for ephemera related to other works rather than artworks in themselves. Other arte povera artists gradually evolved to create giant half-dome structures, forests of tree branches and live horses. The “povera” aspect of their work became conceptual rather than actual. Prini’s work remained more low-key. It is often made of the very poorest materials: MDF, rugs and wires. One piece, Perimetro Misura a Studio Stanza (1967), is a roll of tape that Prini used to measure a room. Most of all, there is paper.

Emilio Prini, Consumption Items, 1969. Courtesy Archivio Emilio Prini.

Between sculptures, films, text-based works and photo series, we have contracts, letters, pages from catalogues. It can be a little bewildering. One exhibit includes “part of a comedy strip for four actors” printed on Studio International-headed paper, with a traced outline of Michelangelo Pistoletto’s cover for the October 1966 issue adjacent to it. Another, an untitled work from 1970, features a curt thank-you letter in which Prini is thanked for lending money for an armchair, which is also presented upside down above. The same year, he had 100 photocopies of an authentication document printed for a work exploring the value of art. More approachable are his early 70s typewriter drawings, where numbers, letters and symbols are turned into rudimentary shapes and images.

Emilio Prini, Untitled, 1970. Courtesy Archivio Emilio Prini.

Once Prini seized on an idea, he kept returning to it, morphing it across form and medium. In the late 60s, for instance, he began surveying architectural details in Genoa and Rome. His photographs capture unloved corners, staircases and walls. Prini often depicts himself, shot from behind, a flaneur in his element. In 1995, almost three decades later, Prini revisited some of these works. He created three-dimensional sculptures that re-embodied the architectural forms he had previously flattened into photography.

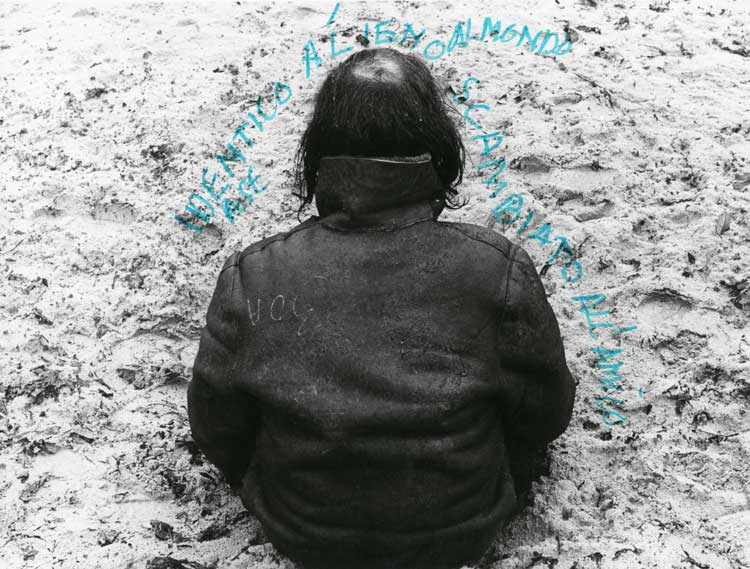

Prini is a difficult artist to exhibit. Many performance artists create works that can be replicated by actors. This might not always be satisfying, but at least we can experience a visual simulacrum. Prini’s happenings are harder to recreate. They often relied on conversation and interchanges between artists. When invited to exhibit at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1969, he refused to show inside, instead pitching a set of tents in a nearby sandpit. Visitors were invited to use candle wax to compose sentences explaining their dependence on others. Prini summarised the process into a bullet-point list on a piece of paper. The event may have been electric, but we are left with a snatched glimpse.

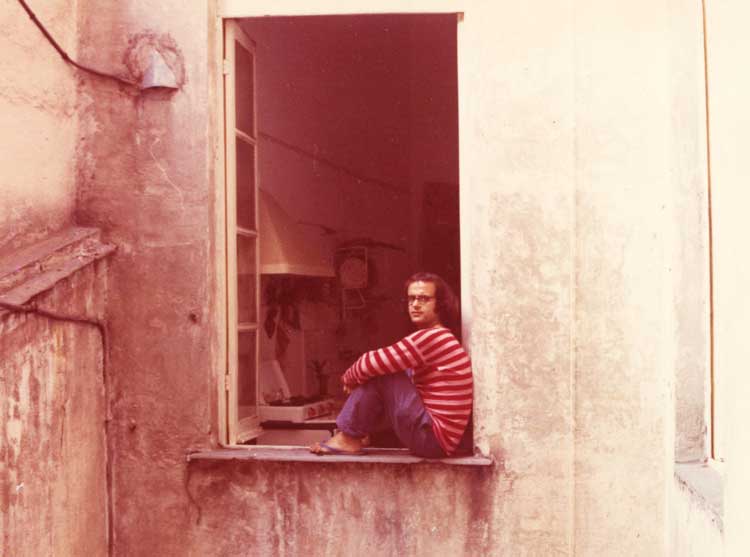

Photograph of the artist dressed as a clown at the window of his studio, Genoa, 1968. Courtesy Archivio Emilio Prini.

What we do have can be fascinating. He made numerous self-portraits with an element of whimsy. The prosaically named Photographic Sequence of the Artist Sitting at the Window of His Studio (1968) comprises 40 colour photographs in which Prini does as the title suggests. He does so in a proto Where’s Wally? outfit of red-and-white striped shirt, plus a fake nose, turning himself into a strange sort of clown. We see him pose in the same position – feet on windowsill, back against the wall, not quite perilously dangling over the edge of a courtyard – from 40 different angles. Prini homes in on the difficulty of creating an objective image of a person or place, while exploring the way a body can merge into an environment. Later, he would augment the costume with a black cape with an “Alieno” (alien) on the front and a red heart on the back. Was he puncturing the seriousness of its contemporaries? Or expressing a feeling of estrangement from them?

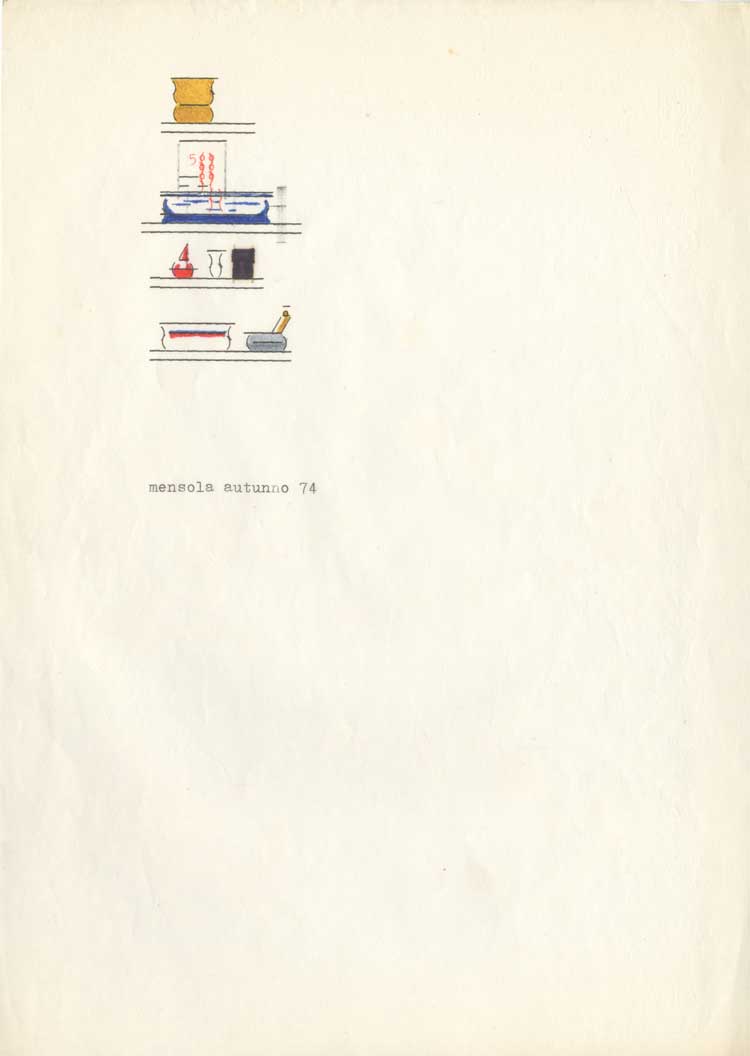

Emilio Prini, Untitled, 1974. Courtesy Archivio Emilio Prini.

A unifying thread of Prini’s practice is a devotion to testing things to their limits: 40 photographs, 1,000 photocopies, 18,915 prints. Among his most fascinating works are those where he used electronic devices to the point of exhaustion. He brought a camera to the end of its life. Later, he would photograph it, turning the camera itself into an object of observation, and then print thousands of reproductions of the image. His contribution to the exhibition Arte Povera 2011 at the Castello di Rivoli was to display the exhibition catalogue opened at the pages concerning himself; visitors were invited to read it until it was worn out. Making and interacting with art gradually leads to its destruction. Prini flips a finger to the art world’s obsessions with authenticity and preservation. This refusal to confirm might well be his signal achievement.