Rino Claessens, Scraped Earth stools.

17-25 October 2020

Eindhoven, The Netherlands

by VERONICA SIMPSON

It was always going to be a tall order to deliver on a promise to explore the theme of “the new intimacy” in a 2020 design festival, but doubly so when Dutch Design Week – which had been planning a part-virtual, part-real life programme – went entirely online as coronavirus cases in the host city of Eindhoven escalated. Unfortunately, the online press viewing ended up as a showcase for the kind of technical glitches that do anything but foster a sense of intimacy. The scheduled Zoom link failed to materialise. The accompanying YouTube livestreamed talk kicked in 15 minutes late, and without sound for the first five minutes. Then the elaborate choreography required of the presenter, Champ Bouwman, of the Netherlands tourist board, as he danced around his studio with and without a mask to safely usher in each socially distanced interviewee made for a faltering, amateurish experience that did nothing to recommend this new, virtual approach. Which is a shame, because, if any design community could do a decent virtual design week, it would be that of Eindhoven, arguably the Netherlands’ most innovative city and home of northern Europe’s most cutting-edge design college, Design Academy Eindhoven (DAE).

Dutch Design Week is effectively a showcase for DAE’s graduates and alumni. Now in its 15th year, it remains the largest, non-commercial design event in northern Europe. In normal years, 2,500 designers are represented and 350,000 visitors attend events at more than 100 buildings. Part of the allure is Eindhoven itself, one of Europe’s leading 21st-century exemplars of how the right combination of enterprise and creative education can reboot a city built on 20th-century manufacturing. The electronics company Philips, founded in Eindhoven in 1891, was the power behind the city, designing and building everything from light bulbs to sound systems and washing machines. But when its business and geographical locations diversified, the disused factories and streets on its campus were slowly reinvented as studios for artists and makers, start-up spaces and housing. That combination of cheap, available space and the city’s strengths in technology and design have created a natural home for the graduates of DAE, many of whom stick around to make their mark on the world with a typical flair for critical, speculative, multidisciplinary design projects that make us question the how and the why of design, as much as the what and the who; it is often design with a social heart, as well as an environmental perspective.

So what treats lay in store for us in this 2020 virtual iteration of the festival? The designers who were cherry-picked for the press’s first hour-long (albeit technically truncated) presentation were an interesting crew. From Freek van Welsenis of Hable Accessibility, we had a heartening project, a smartphone controller designed for blind or visually impaired people, which he co-designed with his grandfather. A great product, clearly, generated by a demonstrable need – there are apparently 300 million people globally who are visually impaired, for whom smartphones are currently of little value.

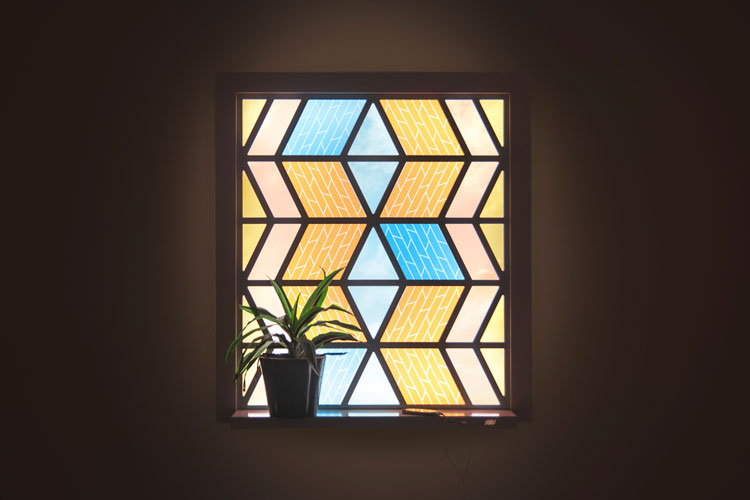

Marjan van Aubel’s tinted window panels.

Next, we had some attractive solar projects from Marjan van Aubel, whose mission is to weave access to this free source of power into every aspect of our lives. To this end, she has designed an attractive, space-age, solar harvesting table, a series of prettily tinted window panels and a lamp that hangs in the window and is powered by the sunshine which it harvests during the day.

Tim Teven’s furniture.

Tim Teven showed us a range of furniture he has made by moulding leftover paper fibres from the recycling industry into furniture. It is a good move to try to harvest a material that most people do not realise usually ends up in landfill - once paper has been recycled six or seven times, it cannot be processed further. But while he had taken great pains to develop a product that looked and felt organic, he admitted most of his larger items are extremely heavy and difficult to move. Which raised the question of whether it is suitable for furniture, or whether turning it into street furniture or security barriers would be preferable?

Laura Luchtman and Ilfa Siebenhaar. Design to Fade; Living Colour x PUMA. Photo: Ingo Foertsch.

The last two showcased designers were Laura Luchtman and Willem Schenk. Luchtman has developed commercial dyes that take their pigmentation from bacteria rather than chemicals, and showed us her first collection of sportswear in collaboration with Puma. Schenk is turning his back on 21st-century design and urbanism to curate a “Landscape Triennial” for the countryside, which will launch in 2022. It is necessary to reframe our love of cities and return to the country in order to move ourselves and the planet back into balance, he proposed, even going as far as to say that, in the future: “Anything that concerns us will be produced by farmers.” This reversion to simplicity and rusticity, for the sake of sustainability, is being supported by Li Edelkoort, chairwoman of the DAE for a decade, until 2008, arguably its most influential years. So is design, as this innovative school has promoted it so far, now dead?

You might think so if you stayed online for the next hour’s tour of the show, a kind of Pecha Kucha-style presentation of a dozen DAE alumni. Much of what they presented was neither new nor logical, such as using miniature drones as studio assistants, bringing designers cups of tea or – more ludicrous still - to weave oversized sections of fabric. The point of good design is surely not to deploy technology in such a way that the process becomes more time-consuming and cumbersome than when carried out by a human. However, this depressing roster of relatively mundane projects perhaps said more about the difficulty of finding a way to realise radical or fabulous ideas that might benefit humanity or society in a market that prioritises monetary value and profit over human wellbeing.

Somewhat disappointed, I turned to what is always said to be a highlight of the show – a look at the DAE graduate work. And so it proved to be.

Anders Juul Jørgensen’s virtual reality experience Garden of Elysium

I was drawn immediately to a project by Anders Juul Jørgensen, a spiritual virtual reality experience called Garden of Elysium. It places the viewer in a zen garden with flowers and running water, and rewards them for their calmness: only when the viewer breaks their meditative state and starts to explore the virtual landscape do the surroundings morph into something altogether more dystopian. If, through tools such as this, we could learn to control our anxious and distracted minds, that would truly be of benefit to humanity.

Adi Ticho’s Unveil.

Adi Ticho’s Unveil also used technology in a socially beneficial way: she proposed that the temporary partitions that are often thrown over balconies in Jerusalem could be used as a screen, which, when viewed through a Chroma key app, would project poems and statements reflecting the reality of a culture that discriminates against women in the name of “modesty”. This, she says, would be “a form of protest that respects belief systems while engaging with the dialogue around the nature of public space”.

Boey (Bo) Wang’s award-nominated project Immeasurable Range introduced four seductive products that help to articulate, but also make beautiful, the things that make us insecure and anxious. My favourite was a rubber ruler that indicates the distance you are from whoever you are addressing, but also “extends as emotional tension rises”. I also liked his 3D reflective set-square, which demonstrates the way our perceptions and attitudes are formed from the very particular place where we are standing – and not necessarily shared by those nearest to us. There is also a flexible spirit level, “suggesting that relative flatness might be curved”.

Anna Dienemann’s Bounding Spaces project.

Anna Dienemann addressed social boundaries with her Bounding Spaces project, which she calls a “playful, fashion-driven answer to the current crisis”. A colourful, skirt-style accessory inspired by pop-up-tent technology, it inflates when the wearer wants to ensure safe social distancing is observed. There are seven models to choose from in flamboyant prints and colours, with contrasting outlines to frame your personal space as you like. When the risk has passed, they are compressed down into a colourful belt.

Critical thinking melded with infographics is a burgeoning field in the visual arts, as demonstrated by the success of the UK’s Turner Prize-shortlisted Forensic Architecture collective. It is that sort of territory that Anna Oberthaler’s project occupies. The Infinite Resource looks at how marine species are being exploited for their rare genetic materials. Currently, a few globally powerful pharmaceutical companies are staking ownership of certain types of marine DNA when, as Oberthaler says, we should all be sharing in that bounty. Her Infinite Resource video installation “reveals the tension between ecological protection and political and economic exploitation”.

It is not all angst and outrage, however. Humour makes an appearance in graduate Arthur Jacquet-Usureau’s project, My Summer-camp Graduation, which offers giant, colourful Scoubidous, which can be knotted into a range of fun and silly objects for interactive, IRL play.

Baptiste Comte’s Mementum.

From the playful to the funereal: Baptiste Comte has created Mementum, a series of classical but quirky funereal vessels made of clay: a place to store the ashes of loved ones that is aesthetically appealing and individual. Using 3D-printing technology, he offers an infinite multitude of variations to evoke the colours, qualities and character of each person they are intended to commemorate. The idea is that these can be used as a decorative memorial either in the home or in public, or sealed in a degradable container for eventual burial.

Benjamin Motoc’s stools.

There is precious little in the way of practical furniture emanating from DAE, as you might expect. But there were some interesting alternatives. Benjamin Motoc has abandoned the uniformity of standard industrial moulds for a production line that generates a unique outcome with each casting. By combining unusual materials such as molten wax with an ice mould, each of the stools pictured in his presentation is different and offers a very distinctive appearance, looking like fossilised growths or fungi.

Clara Roussel’s Touching Memories.

Clara Roussel’s sofa was another leftfield and joyous invention. Her project Touching Memories is inspired by happy recollections of playing on a couch in her grandparents’ house. Roussel’s “Jackie” is a new kind of sofa, interpreting those specific memories through shape, feel and colour. In this way, she invites you to share her memories, or suggests she could tailor bespoke new furniture to evoke your own.

At a time of increasing isolation, it was not surprising that mental health emerged as a strong focus. Bianca Carague created Bump Galaxy, a virtual world and community for mental health. She is promoting the idea of deinstitutionalising healthcare by bringing people – patients and carers – into a virtual space that allows for shared and beneficial experiences. Players visit a variety of “care commons”, including a meditation forest, dunes for reflecting on your dreams and an underwater temple designed “for hypnotic imaginings”. They can also meet health professionals from across the world. In this way, she hopes new practices and knowledge might be created, and archived in open source community care records.

Dae Uk Kim’s project Mutant.

Gender politics also popped up, most notably in south Korean designer Dae Uk Kim’s project Mutant, which was triggered by the feelings of exclusion he experienced as a gay man growing up in South Korea’s heteronormative world. Kim assembled a series of objects that might usually be considered “uninteresting and inferior, mutating them into something more grandiose and superior as a way of encouraging people to consider the implicit boundaries around gender that exist in different cultures and societies around the world”. I have no doubt this would be far more powerful to experience in the flesh, though the image on the graduate website is intriguingly dystopian.

Coltrane McDowell’s Olfactory Bio-politics.

Coltrane McDowell’s Olfactory Bio-politics: Nairobi should also, presumably, be experienced in real life, given that it relies on the sense of smell. He has created a three-video installation featuring case studies from Kenya, exploring different dimensions of how particular smells make us feel, but with particular relevance to problematic spaces and issues in Kenya. For example, one explored the repercussions of the global lockdown on Kenya’s rose economy: Kenya usually supplies around 70% of Europe’s roses, but much of its summer 2020 harvest was dumped due to the cancellation of flights and trade. Another visits informal alcohol brewers in a Nairobi settlement. The videos are designed as part of an immersive experience, along with the accompanying scents and additional elements that form part of McDowell’s studies into smell as a lens for design research.

I expect and hope to see many – or all – of this “class of 2020” at future Dutch Design Weeks. But for these projects to be realised, we have to hope that a different kind of market will emerge, post-pandemic, which favours projects that enrich the human experience and prioritise wellbeing over enriching the corporations or venture capitalists that fund them. We can but dream.