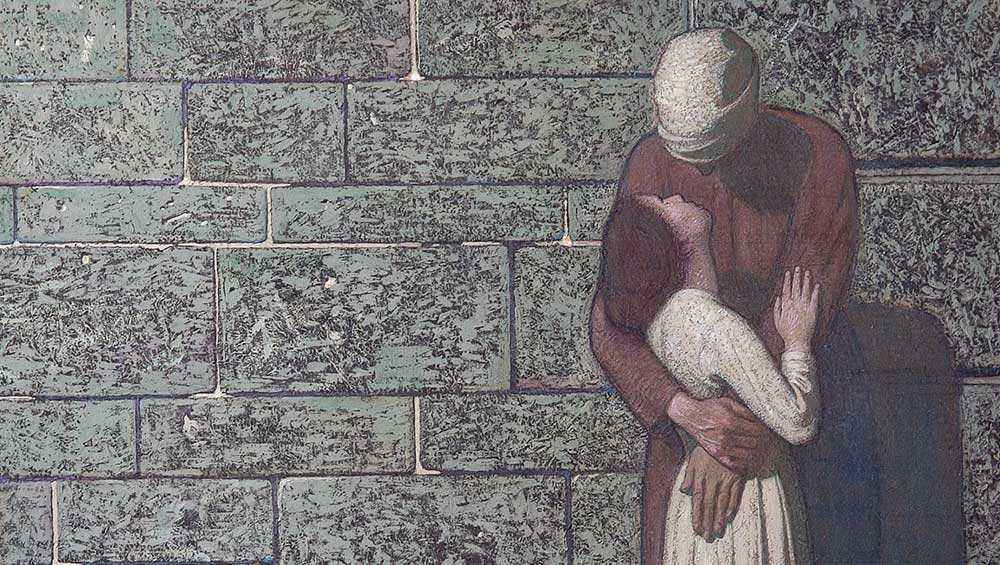

Frederick Cayley Robinson, The Farewell, 1907 (detail). Tempera on board. Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, Warwick District Council.

Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village, Compton, Surrey

18 October 2022 – 26 February 2023

by ANNA McNAY

This small gem of an exhibition, adapted for Watts Gallery – Artists’ Village from one held earlier this year at Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, from where a good number of the works have been lent, is the third in a series of exhibitions showcasing artists from different stages of pre-Raphaelitism – early, mid and now modern. Indeed, many of the artists falling under this rubric are often simply considered modernists, or part of the wider European symbolist movement, but the pre-Raphaelite aspects of their work are apparent, not least their frequent focus on dreams and stories, as the exhibition title suggests. This focus on dreams, as well as connections with GF Watts, is what distinguishes this iteration of the exhibition from its predecessor.

During the 50 years this exhibition considers, from 1880 to 1930, Britain underwent many changes, brought about by industrialisation, increasing social mobility and war. Many artists working at the time were drawn to modern life while simultaneously looking back to the past in an attempt to understand their changing world. The dreamy beauty and apparent simplicity of the works of the pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were, perhaps unsurprisingly, enticing. The original pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was established in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. This original group separated after a few years, but a second wave of artists, including Edward Burne-Jones and Simeon Solomon, followed in their footsteps, further exploring the ideas of colour harmonies and art for art’s sake. By the 1880s, however, it was this third wave of “modern pre-Raphaelites” who picked up the mantle.

Walter Crane, Love's Altar, 1870. Oil on canvas. William Morris Gallery, London Borough of Waltham Forest.

It was in 1900, near the midpoint of the period under consideration, when Sigmund Freud burst on to the stage with his groundbreaking theory of psychoanalysis and the publication of The Interpretation of Dreams, which had a resounding impact across Europe. One of the paintings included here by Watts is a portrait of his “symbolist muse”, Violet Lindsay (c1879), so dubbed because there is a departure from his early, much more typically pre-Raphaelite, style, in which symbols were used to allegorically explain the virtues of a character (hope, love, despair …), moving instead to focus on the psychology and emotions of his contemplative sitter. Freud’s thesis similarly explored the idea of the unconscious and the ways in which dreams might offer a gateway to subconscious feelings and memories. Alongside Watts, Frederick Cayley Robinson, in particular, who features large in this exhibition (with a lot of his works being held in the Leamington Spa collection), created dream-like worlds in his illustrations, paintings and set designs. These works were often uncanny or unsettling, with familiar objects appearing out of context.

Frederick Cayley Robinson, The Night Watch, 1903. Mixed media on gessoed board. Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, Warwick District Council.

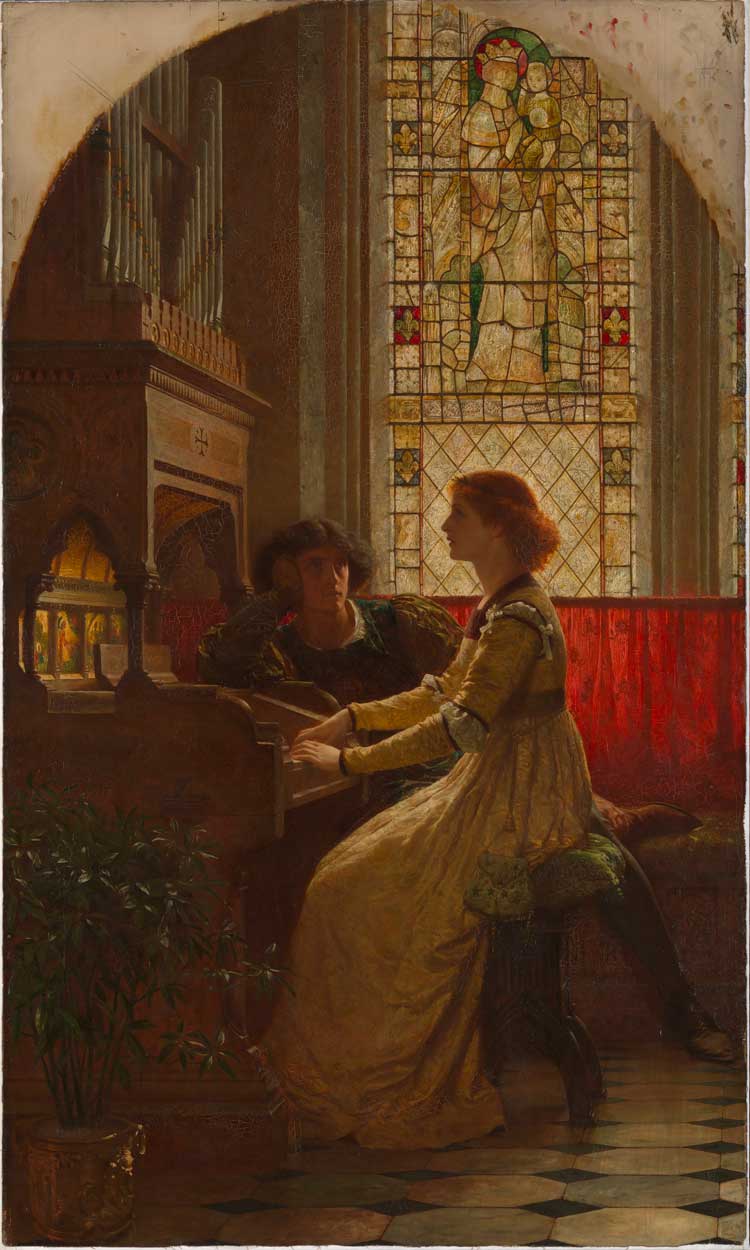

There is the stuff of nightmares, too. Sinister undertones are clear in The Foundling (1896), for example, where the young girl, sitting on the floor in front of the fireplace, nearly ready to go to bed, on closer inspection has a bandaged foot (with blood seeping through) and has listlessly dropped her cup and spoon. The ginger cat, bristling away from her, looks frightened, and the somewhat terrifying firedogs cast an ominous V-shaped shadow. The Close of Day (undated), also by Cayley Robinson, is similarly complex, and certainly has its share of uneasy undercurrents, albeit less inauspicious than in The Foundling. The critic Martin Wood wrote in this journal in 1910: “The significance of the picture seems not to lie in the scene, but in the feeling that the fates themselves are concealed – that something is portending.”1 This idea of something unspoken is emphasised by the music box on the table playing one of Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words. The detail here is minute. There are also images within images – both the religious triptych at the back of the composition and, less overtly, the highly polished chest of drawers at the front left, in which the back of one of the girls is reflected.2 The orange light of sunset falls in a band across the white muslin dress of the same girl in an exquisite fashion. Similarly beautiful fine detail and rendition of light can be enjoyed in Frank Dicksee’s Harmony (1877), hanging nearby, in which the stained-glass window allows tinted sunbeams to fall on the white fabric of the seated girl’s dress.

Frank Dicksee, Harmony, 1877. Oil on canvas. Tate.

A more overt and awake sense of danger is apparent in Frank Cadogan Cowper’s St Agnes in Prison Receiving from Heaven the ‘Shining White Garment’ (1905), where the girl cowers, naked but for her long red locks, in the corner of a straw-bedded cell. While St Agnes might, here, be given a typically pre-Raphaelite appearance, the context of her martyrdom places this portrayal of a woman – along with Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Joan of Arc (1864) (from before the period of this exhibition but included nevertheless) –beyond the idealised Victorian constructs.

Eleanor Fortescue-Bricksdale, The Guardian Angel, 1910. Oil on canvas. (Monmouth Museum), Image Courtesy of MonLife Heritage.

Another popular way to depict women – and angels – especially in the wake of the first world war, was in a protective role. An example of this is found in Eleanor Fortescue-Brickdale’s (albeit pre-war) The Guardian Angel (1910), where the angel protectively cups his hands around a biplane. The painting was made in memory of Charles Rolls, a pioneering aviator and motorist, and one half of the Rolls Royce Company, who was killed when the tail broke off his Wright Flyer aeroplane during an aeronautical display. The picture is quite marvellous in its modern content (a plane!) and yet still very Victorian in style, as well as in its inclusion of elements and motifs – the aura of light around the plane and the flock of blue birds – to be discussed more later in relation to their inclusion in other works in this exhibition (by Evelyn De Morgan and Cayley Robinson respectively). If anything, this painting, hanging in the opening gallery space, might be viewed as embodying many of the main characteristics of a “modern pre-Raphaelite” work. Another of these is the use of primarily blue tones – something, again, usually associated with symbolist paintings (think, especially, of works by the Belgian painter Paul Delvaux).

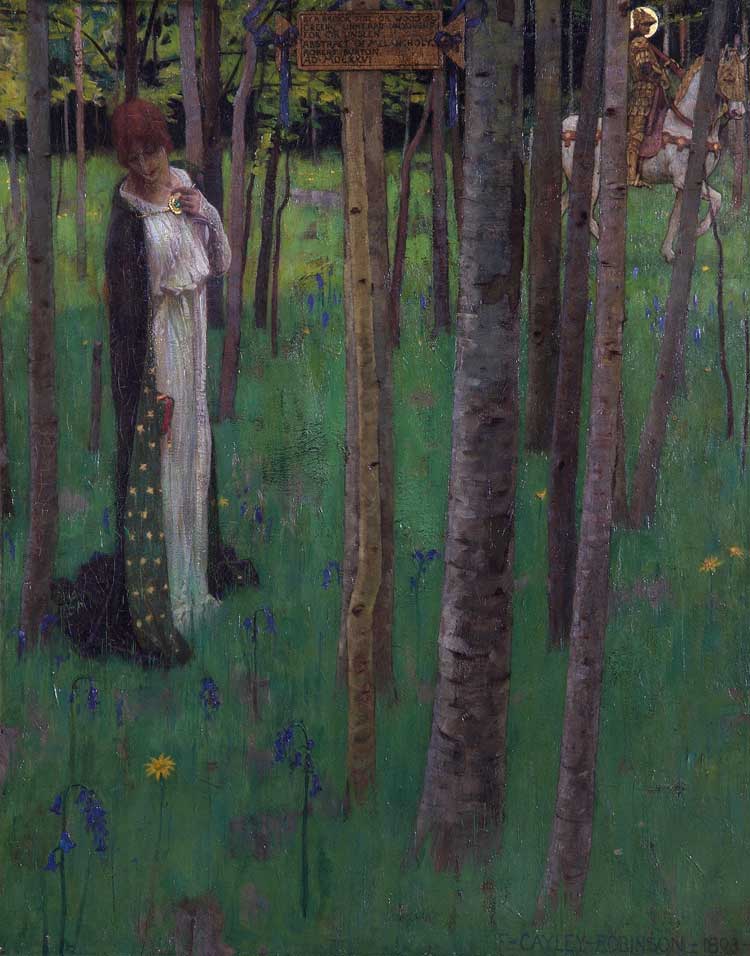

Frederick Cayley Robinson, In a Wood So Green, 1893. Oil on canvas. Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, Warwick District Council.

The works on the facing wall as you enter the main gallery space are arranged such that there is a cascade of green to blue hues, from Rossetti’s The Damsel of Sanct Grael (1857) (another earlier work by Rossetti, included, one assumes, for comparison), with her green robe and blue undergarment, through the bluebell-studded grass of Cayley Robinson’s In a Wood So Green (1893), to the evening light through the green glass window in Marianne Stokes’ Candlemas Day (c1901). In a Wood So Green makes me think back to Lizzie Siddal’s works full of Arthurian legend (as does The Farewell, 1907, also by Cayley Robinson), while simultaneously looking forward to the scenes of the north German Teufelsmoor, with its upright birches, by Paula Modersohn-Becker and Otto Modersohn, and, indeed, the Austrian forests of beech, birch and fir by Gustav Klimt, painted in the early 1900s, and often spoken of in relation to symbolism, with the trees seen as a spiritual and transcendent motif. In terms of looking back, Cayley Robinson’s painting corresponds with Walter Crane’s description of how Burne-Jones created “a magic world of romance and pictured poetry, peopled with ghosts of ‘ladies dead and lovely knights’, - a twilight world of dark mysterious woodlands, haunted streams, meads of deep green starred with burning flowers, veiled in a dim and mystic light.”3 In terms of looking forward, or at near-contemporaries, however, it is probably more interesting to note the vast differences between this modern pre-Raphaelite style and some of its contemporaries. One striking example would be to compare Robert Anning Bell’s highly traditional The Listeners (1906), in which a crowd of women appear awestruck, potentially as if receiving a message from on high, but also described as exploring the concept of synaesthesia, with the expressionist and abstract works of Wassily Kandinsky (from around 1910), himself a synaesthete. There could scarcely be a more divergent comparison.

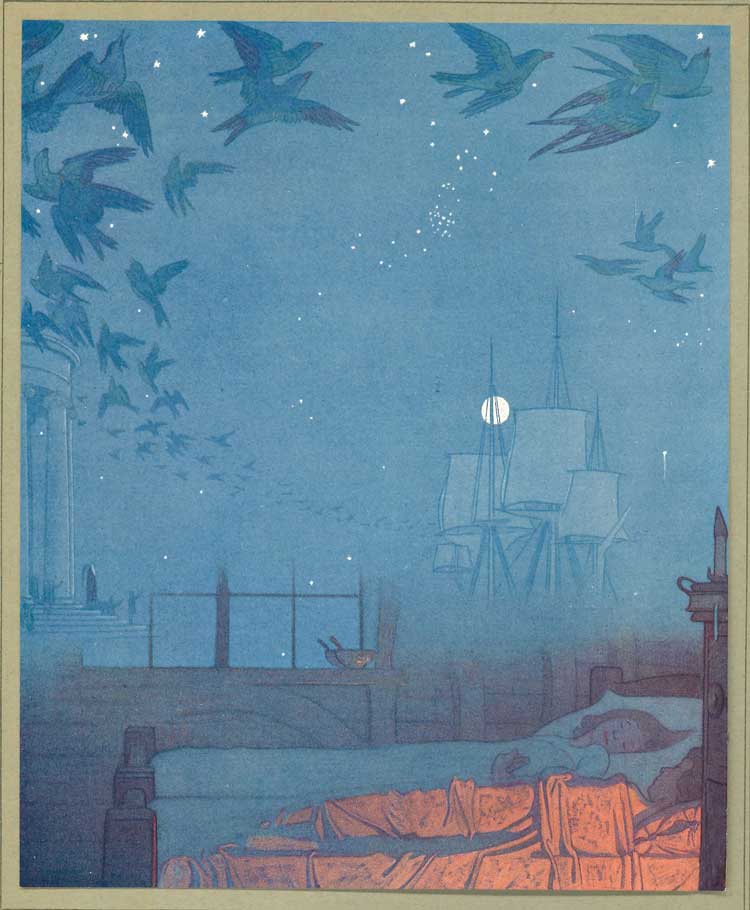

Frederick Cayley Robinson, The Blue Bird, 1911. Print on paper. Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum (Warwick District Council).

As we arrive at blue, we once again meet Cayley Robinson, who, having created set and costume designs for the first staging in England of the Belgian playwright Maurice Maeterlinck’s symbolist play The Blue Bird (1909), made watercolour illustrations, which were reproduced in an illustrated book edition. Once again, the subject matter is oneiric – two children asleep in bed, with a ship sailing (towards them or away? It is unclear) through a star-studded, moonlit sky, with a flock of birds circling overhead (here is my reference back to the birds in Fortescue-Brickdale’s painting). In Maeterlinck’s play, the children undertake a dream-journey in search of the elusive blue bird, which symbolises happiness. In a letter to Cayley Robinson, Maeterlinck wrote: “You have interpreted the story from within, instead of translating it from without,”4 which loops neatly back to Freud.

Evelyn De Morgan, Evening Star Over the Sea, probably 1910-14. Oil on canvas. De Morgan Collection, Courtesy of De Morgan Foundation.

One of my all-time favourite paintings in the exhibition is De Morgan’s Evening Star Over the Sea (c1910-14), which is more spiritual then oneiric (and, as an interesting aside, the artist had been bequeathed the visionary crystal of her psychic healer and clairvoyant mother-in-law). The body of a woman floats in a blue sky, above blue water, wearing a diaphanous blue dress, and radiating an effulgent circle of purple and orange light (my second reference back to Fortescue-Brickdale’s work), said to represent the aura emanating from the human soul. Perhaps this suggests that the subject, through death, has become a shining star? As such, it is not so much a work about dusk and the end of a life as it is about rebirth and dawn. The late 19th century had seen a growing interest in spiritualism and the occult, with the advent of theosophy, and this inspired the modern pre-Raphaelites to explore the mystical and the unexplained in their work. Spiritual or supernatural subjects allowed artists to consider their place in an ever-expanding and abstruse world, especially faced with the mass deaths of the first world war. De Morgan was unusually successful during her lifetime, enabling her to financially support her husband’s ceramic practice – something quite anachronistic. It is funny how certain works make such an impact. Until I relooked at the installation shots for this exhibition, I had misremembered this painting as being much larger. (Interestingly, this is the study for a larger painting that was never completed.) It makes me think of The Sun (1909) by Edvard Munch, an artist who also comes to mind when looking at the amorphous, shadowy figures in pieces such as William Shackleton’s Wings of Silence (undated). In fact, one could be forgiven for misattributing several works in the exhibition to the Norwegian symbolist.

Another all-time favourite of mine, included here, is Solomon’s Sleepers and One That Waketh (1870-71), with its three androgynous heads embracing against a star-studded midnight-blue sky. Like so many of the works in this exhibition, this one has no definite subject, concerning itself more with the idea beyond, spiritual potential, dreams, and the state(s) between sleeping and waking. Watts’ statement – “I paint ideas, not things” – would be apt here, as for many of the works in this exhibition.

Thomas Cooper Gotch, Alleluia, exhibited 1896. Oil on canvas. Tate.

When one thinks of the pre-Raphaelites, the image of a woman is very much a full-red-lipped muse, with flowing auburn hair, as depicted by the men of the Brotherhood, and epitomising Victorian ideals of beauty. As we have already seen, however, there were women making a success of it as artists during the modern pre-Raphaelite era (which, of course, spans the emergence of the modern woman and the suffrage movement), and many of these were interested in finding new ways of painting women. Artists including Margaret Gere, Christiana Herringham and Stokes, for example, played a significant role in shaping modern devotional images of women, as well as exploring other religions in their work. They also promoted an interest in Renaissance and medieval art through their revival of egg tempera painting. The pre-Raphaelites, although imitating this medium, had never used it. Stokes’ Candlemas Day is a good example and is really very different in perspective from Thomas Cooper Gotch’s Alleluia (exhibited 1896), also on display. Whereas Gotch’s work is ornate and celebratory, Stokes’ painting focuses on a silent sanctity and religious introspection, with the suggestion that the gridded green glass behind her might represent a Catholic confessional screen (it is, however, also echoic of the window in The Close of Day, although the colour there might well come from the curtain rather than the glass). The 13 young pre-Raphaelite faces gazing piously from the gilt, medieval-style composition of Alleluia – only one girl dares meet the viewer’s eyes – do so from beneath an array of incredibly modern bobbed and fringed haircuts, however, showing that even some of the modern pre-Raphaelite men portrayed “modern women”.

I confess I was shocked by how few of the exhibited artists’ names I knew, and I came away feeling educated and enchanted in equal measure. The curation is tight and telling, and I am sensible of having slotted a few more pieces into my mental jigsaw of artists and art movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. I know the pre-Raphaelites are a bit like Marmite (you either love them or hate them), but don’t write this off as just more saccharine sycophancy – while providing the schmaltz that those who love it love, the exhibition has scope way beyond into the spiritual, the subconscious, the social and the symbolist. In our own times, these artists have been overlooked or seen as old fashioned when compared with contemporaneous movements that sought to radically break ties with art of the past. Under the umbrella of “modern pre-Raphaelitism”, however, they are brought together in an effort to re-establish their role in modern art by exploring how looking back allowed them to move forwards into the uncharted modern world.

References

1. Some Recent Work of Mr Cayley Robinson by T Martin Wood, in The Studio, 49, 1910, page 204. Cited in: Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries: British Art 1880-1930, exhibition catalogue, Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, 2022, page 72.

2. The National Gallery, London, hosted an interesting exhibition considering the common use of reflections as a Pre-Raphaelite device: Reflections: Van Eyck and the Pre-Raphaelites (2 October 2017 – 2 April 2018).

3. An Artist’s Reminiscences by Walter Crane, published by Methuen & Co, 1907. Cited in: Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries: British Art 1880-1930, exhibition catalogue, Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, 2022, page 7.

4. Frederick Cayley Robinson: Mystical Modern by Sarah Victoria Turner, in: Modern Pre-Raphaelite Visionaries: British Art 1880-1930, exhibition catalogue, Leamington Spa Art Gallery & Museum, 2022, page 69.