Paul Cezanne, The Sea at L’Estaque, 1878-79 (detail). Oil on canvas, 72.8 x 92.8 cm. France, Paris, musée national Picasso-Paris, donation Picasso, 1978. Collection personnelle Pablo Picasso. © RMN - Grand Palais - Mathieu Rabeau.

Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence

28 June – 12 October 2025

by JULIET RIX

“If you are born here, that’s it, nowhere else can ever quite compare,” said Paul Cezanne (1839-1906) of his home town, Aix-en-Provence. He was born, brought up and died here and, although he spent time in Paris and other parts of France, he kept returning to Aix throughout his life and particularly to Jas de Bouffan. This 18th-century country house and working estate was owned by the Cezanne family for 40 years from 1859, when Paul was 20, until 1899 – and alongside this exhibition, it has just (re)opened to the public.

It was at Jas de Bouffant that Cezanne did some of his first independent art – not only within its walls, but also on them – and from 1882 had a purpose-built studio. Here, he developed his landscapes – repeatedly painting the house and its grounds – and still lives, made portraits of friends and family and used the farm labourers as models, including for now-famous paintings such as The Card Players. From here he painted his first views of Mont Sainte-Victoire and set out for his earliest painting trips to the nearby Bibémus quarries with their striking geometric, red-yellow rocks. Examples of all these feature in this exhibition.

Paul Cezanne, Maison et ferme du Jas de Bouffan, 1885-87. Oil on canvas, 60.8 x 73.8 cm. National Gallery Prague. © National Gallery Prague 2025.

Jas de Bouffan was central to Cezanne’s emotional and artistic life, and the house itself – 20 minutes’ walk from the exhibition – has just been restored. In fact, it was this restoration and the opening to visitors of new areas – including Cezanne’s remarkably modern-seeming top-floor studio – that prompted the show. The house and exhibition offer different angles on the same story.

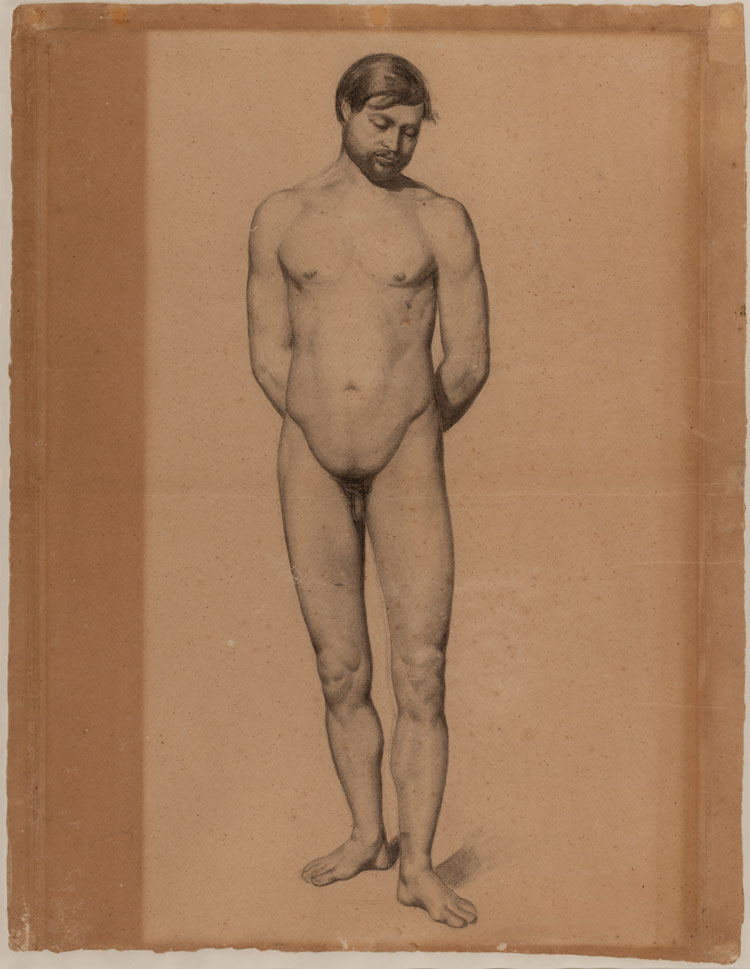

The exhibition is in an historic Cezanne setting, too, occupying the very rooms in which the young Cezanne first learned to draw and paint. What is now the Musée Granet was in his day Aix Museum and Free Drawing School, and Cezanne sketched classical casts and copied paintings here. The first room of the exhibition includes an early contemplative sketch of a male nude (Male, Academy, 1862) and a largely faithful copy of the Muse’s Kiss (1857) by Félix-Nicolas Frillié.

Paul Cezanne, Male, Academy, 1862. Graphite on paper, 61.5 x 47.8 cm. Aix-en-Provence, musée Granet, fonds de l’École de dessin, 1862. © Claude Almodovar / musée Granet, Ville d'Aix-en-Provence.

In the first room also is a little aside: documentary evidence that Cezanne’s name is indeed Cezanne and not, as so often spelt in art history, Cézanne. His father’s birth certificate is here with his name spelt Suzanne, along with a legal correction of this clerical error confirming his name as – accent-free – Cezanne.

The next room is a key part of the show – a reconstruction of the Jas de Bouffan Grand Salon as it was in about 1870. Cezanne’s father, a hat-maker turned wealthy banker acquired the status-enhancing estate from an indebted client in 1859. Despite Cezanne senior’s ardent desire for his son to follow him into a money-making profession (he tried to force him into law and banking), he nonetheless gave him the Grand Salon in which to paint, and between 1860 and 1870 Cezanne created a series of images on the walls that take him from student imitator to recognisably Cezanne.

The 20th-century owners of the house had the paintings removed and put on to canvases, then sold them off, spreading them far and wide. This exhibition brings almost three-quarters of them back together, placing the canvases on to dark red walls (the colour evidenced by research at the house and believed to have been chosen by Cezanne) alongside photographic reproductions of the missing murals. It’s an intriguing display.

Paul Cezanne, The Four Seasons. Left to right: Le Spring, circa 1860; L’Été, circa 1860; L’Automne, circa 1860, L’Hiver, circa 1860. Oil painting on plaster wall, laid down and mounted on canvas. Petit Palais, musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, Don des héritiers d’Ambroise Vollard, 1950. © Grand Palais Rmn / Agence Bulloz.

The earliest of the surviving pictures are The Four Seasons (c1860, Paris Musee des Beaux-Arts). Female personifications, with Spring looking almost pre-Raphaelite, they are signed “Ingres”. Why Cezanne did this nobody knows, though many have speculated, often suggesting it was a nod – ironic or otherwise – to his father’s taste in art. A few years later and in marked stylistic contrast, a portrait of Cezanne Sr was added (The Painter’s Father, Louis-Auguste Cezanne, c1865), like a central image on an altarpiece.

Paul Cezanne, Les Grands Arbres au Jas de Bouffan, c1883. Oil on canvas, 65 x 81 cm. The Courtauld (Samuel Courtauld Trust), legacy Samuel Courtauld, 1948. © The Courtauld.

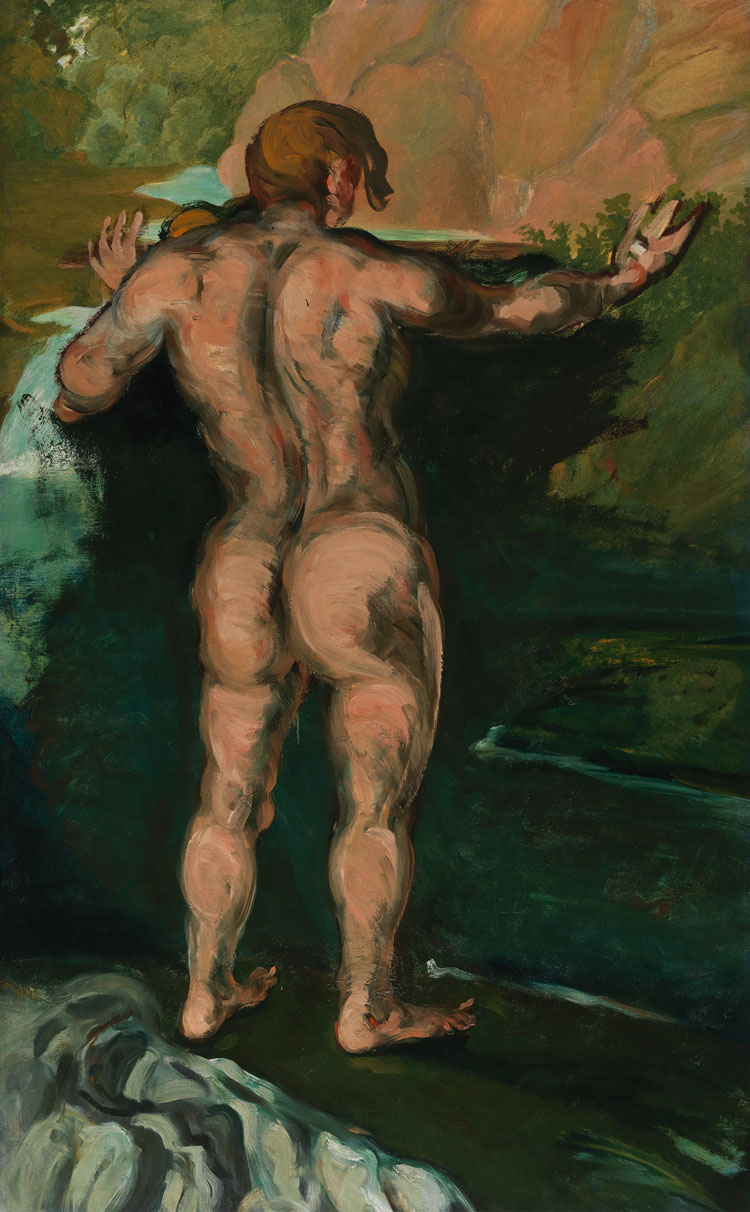

Here, too, are landscapes inspired by Claude Lorrain and Jacob van Ruisdael, a game of hide-and-seek after Lancret (1862-64) as well a couple of religious subjects, a portrait of Cezanne’s friend, fellow Aix artist Achille Emperaire (1867-8), and a study of heads (Contrasts, 1870). In 1867-69, Cezanne added a figure to his 1862-64 landscape Waterfall. Bather and Rocks is recognisably by Cezanne – a male nude with a typically solid body marked out with black lines and palette-knife-applied paint, characteristic of the artist’s so-called “couillarde” or “ballsy,” period.

Paul Cezanne, Bather and Rocks c1867-69. Oil painting on plaster wall, laid down and mounted on canvas, 167.6 x 105.4 cm. Chrysler Museum of Art; Don de Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. © Chrysler Museum of Art.

The show then moves on to individual paintings. There are a number of interesting portraits, particularly of the Jas de Bouffan inner circle. An early double-sided canvas depicts Cezanne’s mother, to whom he was very close, on one side and his sister Marie on the other (1866-67, Saint Louis Art Museum), each with a headscarf but the tone is different. The picture of Marie is an early example of Cezanne marrying the person and the background through colour and brushstrokes.

Paul Cezanne, The Artist’s Father Reading L’Événement, 1866. Oil on canvas, 198.5 x 119.3 cm. Washington, D.C., National Gallery of Art, Collection de M. et Mme Paul Mellon. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Cezanne’s father reappears in The Artist’s Father Reading L’Événement (1866, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC). The father-son relationship was difficult. The father disapproved of his son’s art, which did not earn him a living, but nonetheless supported him financially for most of his life, enabling him to paint. This picture is a portrait and a sort of personal manifesto or statement by the young artist. Behind the sitter hangs one of Cezanne’s own still lives – the original of which rather wonderfully hangs alongside the portrait in the exhibition – and the choice of newspaper is by no means random. Émile Zola had recently written in L’Événement in support of Les Refusés, the artists, including Cezanne, whose work had been rejected by the Paris Salon. It is therefore ironic – or poetic – that following (and indeed preceding) years of such rejection, the only Cezanne painting ever accepted at the Salon, in 1882, was this painting.

Paul Cezanne, Nature morte au plat de cerises et aux pêches, 1885-87. Oil on canvas, 50.17 x 60.96 cm. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Don d’Adele R. Levy Fund, Inc., et M. et Mme Armand S.Deutsch. © 2024 Museum Associates / LACMA. Licenciée par Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / image LACMA.

Zola was not just any art critic either. He was a childhood friend of Cezanne’s whom his father would certainly have known. The lifelong connection between the artist and the writer began when Cezanne rescued the newly arrived Zola with his Parisian accent and unfamiliar ways from school bullies. Zola thanked him with a basket of apples, which some say helped lead to Cezanne’s fondness for painting the fruit (see for example, Still Life with Apples, c1895-98, Museum of Modern Art, New York) and his famous statement: “With an apple, I shall astonish Paris.” This is, though, far more likely to have been due to the fact Cezanne painted slowly and apples degrade far less quickly than other fruit.

Paul Cezanne. Portrait of Émile Zola, c1862-4. Oil on canvas. Musee Granet, Aix-en-Provence, France. Photo: Juliet Rix.

There is an intimate little portrait of Zola in this show (1862-64), one of the very few Cezanne works that belongs to Musée Granet. Zola wrote to his friend shortly before this portrait saying: “The other day I had a dream. I had written a beautiful, sublime book that you had illustrated with beautiful sublime engravings. Our two names in gold letters shone together on the first leaf and in this fellowship of brilliance, inseparable for all posterity. It is just a dream, unfortunately.”

It was Zola who persuaded Cezanne to go to Paris – where he gained so much artistically from mixing with the likes of Pissarro, Monet, Renoir and Sisley – and also Zola who observed how Cezanne was drawn back to Aix: “As soon as he got here he talked about returning.”

In Paris in 1869, Cezanne met Hortense Fiquet, a bookbinder who was working as a model at the Académie Suisse where he was studying (having been rejected repeatedly by the École des Beaux-Arts). Hortense became his life partner, mother of his only child Paul, and eventually his wife. It was a complex on-off relationship that Cezanne kept secret from his father for 16 years, fearful he would cut off his allowance. Hortense was, nonetheless, one of very few women Cezanne painted – and he painted her about 30 times. Although she was not a frequent visitor to Jas de Bouffan (even after her relationship with Cezanne was revealed), a couple of early 1880s portraits are included here along with some intimate pencil studies.

Hortense was evidently not an easy person – and neither was Cezanne, obsessed with his painting, socially awkward and frequently depressed, including by his lack of success, which came only very late in his life. There must have been something that worked between them, though, as even when they lived in different cities, he continued to paint her. He seems to have found the intimacy of a sitting with women outside his family too challenging.

Paul Cezanne, The Bathers, 1899–1904. Oil on canvas, 51.3 x 61.7 cm. The Art Institute of Chicago, Amy McCormick Memorial Collection.

© Art Institute of Chicago, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / image The Art Institute of Chicago.

Cezanne did, of course, later produce the Bathers, full of naked women, and there are several earlier sketches of bathers (male and female) in this show, but he apparently struggled with the female nudes. Art critic and friend Joachim Gasquet wrote that he had seen a “magnificent, nearly completed” painting of naked female bathers at the top of the stairs at Jas de Bouffan. “It stayed there three months,” Gasquet said, “and then Cezanne turned it to the wall, and then it disappeared. He didn’t want to talk about it.” Even in the completed Bathers, the women are more artistic shapes than individuals and were apparently modelled using a female artist’s manikin that Cezanne had specially made, rather than from life.

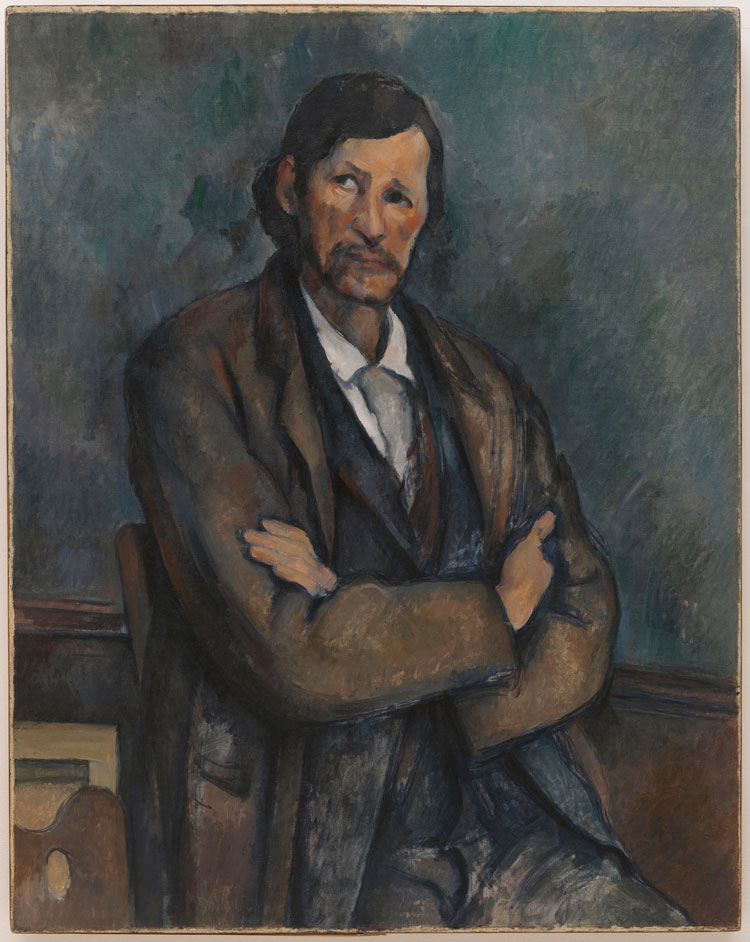

Paul Cezanne, Man with crossed arms, c1899. Oil on canvas, 92 x 72.7 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. © The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art Resource, NY, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn.

Cezanne found Aix “society” difficult, too, and the feeling was mutual; most of Aix disliked or disapproved of his work. He was more at home with the Jas de Bouffan servants and labourers – who were not in a position to be judgmental. They feature in a number of his paintings, almost certainly including Woman with a Coffee Pot (c1895, Musée D’Orsay) – the wallpaper seen here has recently been found at Jas de Bouffan – and Man with Crossed Arms (c1899, Guggenheim, New York). This pair seem to confirm Cezanne’s difficulty connecting with women. It is hard as a viewer to feel a link to the woman dominated by her bright blue dress, whereas the man with crossed arms has character and immediately engages as he looks up at something just beyond the frame.

Paul Cezanne. Woman with a Coffee Pot, c1895. Oil on canvas. Musée D’Orsay. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Local farmhands modelled, too, for The Card Players (1893-5, Musee D’Orsay). The version shown here is the last of Cezanne’s five depictions of the subject, by now intensely pared down to the two players. Cezanne probably took inspiration for the subject from a c1648 painting of the same name by Mathieu Le Nain, which was on view at the Musée Granet in his youth.

Paul Cezanne, The Card Players, 1893-96. Oil on canvas, 47 x 56.5 cm. Musée d’Orsay, legacy Isaac de Camondo, 1911. © GrandPalaisRmn (musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Objects do not require “sittings”, exhortations to stay still or social engagement, and can be employed at any time according to the light. This was perhaps part of the attraction of still lives for an ill-at-ease artist who took a long time to paint. In the studio built for him by his father at the top of Jas de Bouffan, with its huge window cut into the house’s historic wall, Cezanne developed his work with still lives. The Kitchen Table (1888-90, Musée D’Orsay) was almost certainly painted here and is a good example of Cezanne’s very deliberate playing with angle, perspective and point of view as well as colour. Everything is off-kilter yet somehow not unbalanced – just one of many examples of the kind of Cezanne work that inspired the cubists.

Paul Cezanne. The Kitchen Table, 1888-90. Oil on canvas. Musée D’Orsay. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Still Life with Plaster Cupid (1894-5, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm) features one of Cezanne’s most famous props (besides apples) – the white putto now believed to have been made by François Duquesnoy (1597-1643), son of the sculptor of Brussels’ Manneken-Pis. The original can be seen, along with various other of the artist’s props (and the female manikin), in Cezanne’s just restored and reopened Les Lauves studio on the edge of Aix. Clearly modelled on the studio at Jas de Bouffan but larger and more state-of-the-art, Cezanne designed his last workspace himself and had it built in 1901-02 following his mother’s death and the forced sale (due to his brother-in-law’s debts) of the family home.

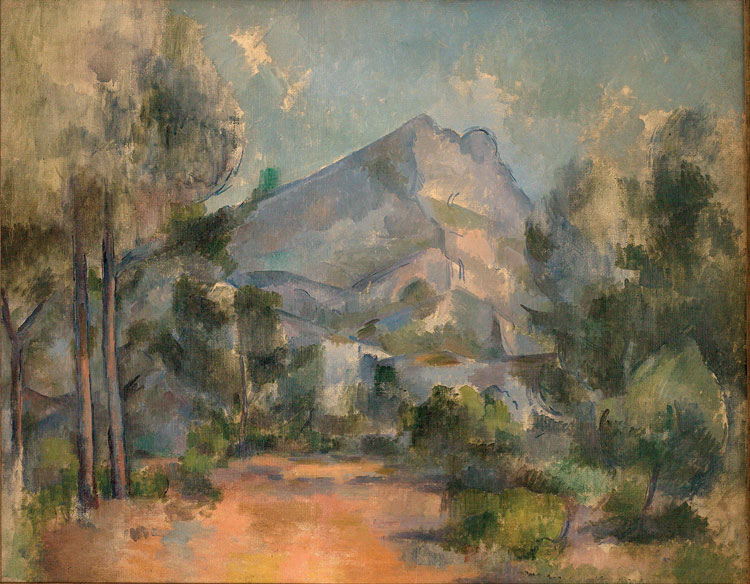

Paul Cezanne, La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, 1897. Oil on canvas, 73 x 91.5 cm. Kunstmuseum Bern, Legacy Cornelius Gurlitt, 2014. Photo @ kunstmuseumbern.ch.

It was on outings from Les Lauves that Cezanne continued to paint the Bibémus quarries (which can be visited on prebooked tours) – represented in this exhibition by the striking and particularly cubist c1895 Essen Museum painting. And from here, too, he painted and repainted Aix’s Mont Sainte-Victoire. His interest in the mountain, though, began while he was still at Jas de Bouffan and this show includes a richly lit 1897 version. This painting was recovered in 2014 from the infamous Gurlitt collection first amassed by Hildebrand Gurlitt amid Nazi demonisation of “degenerate” art and quietly and questionably retained by his son until his death. This work had belonged to the Cezanne family in 1940, and an agreement was reached for the Bern Museum to hold the work but to ensure that it was regularly exhibited in Aix.

Picasso famously bought Chateau Vauvenargues on the north slope of the Mont Sainte-Victoire in 1958. Already the owner of several Cezanne paintings, he credited the older artist as a primary influence (and never painted the mountain himself). Monet described Cezanne as the “greatest of us all” and Matisse called him the “father of us all”. But all this came after Cezanne’s death.

In the artist’s lifetime, the curator of the Aix Museum, now Musée Granet, said: “While I live, no Cezanne will ever enter this museum.” He is presumably turning in his grave as visitors flock to “his” museum to see this intriguing, varied exhibition of 135 Cezannes, bringing Cezanne once again firmly back to his home town of Aix.

• Jas de Bouffan and Les Lauves studio are open until 2 November 2025 and then from spring 2026. Booking is required.