Georg Baselitz: The retrospective, installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 20 October 2021 – 7 March 2022. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

Centre Pompidou, Paris

20 October 2021 – 7 March 2022

by ANA BEATRIZ DUARTE

“I was born into a destroyed order,” reads the very first line at the entrance to the show Baselitz, a Retrospective, at the Centre Pompidou, in Paris. So said by the German artist in an interview in 1995. Baselitz, who is 84 this month, and whose real name is Hans-Georg Kern, has been painting for more than 60 years. The retrospective in Paris is the first to cover all the periods of his prolific career.

The curators, Bernard Blistène and Pamela Sticht, in collaboration with the artist, bring different levels of analysis to Baselitz’s output. Although the work is displayed in chronological order, the exhibition is grouped into thematic clusters, pinpointed by special corners filled with engravings and drawings, as well as paperclips, his art manifestos and other writings.

Georg Baselitz: The retrospective, installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 20 October 2021 – 7 March 2022. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

There are 11 sections, including Discovering the avant-gardes, Fallen heroes, Zeitgeist, The space of memories, From the Russian Pictures to Remix and What remains. Some sections, such as Fractured images and Reversing the image, emphasise the techniques for which Baselitz has become recognised, but it soon becomes clear that they are not restricted to the timeframe they are related to within the exhibition. The same is true in two other sections that highlight the artist’s research at the border of abstraction, another major characteristic in most of his work.

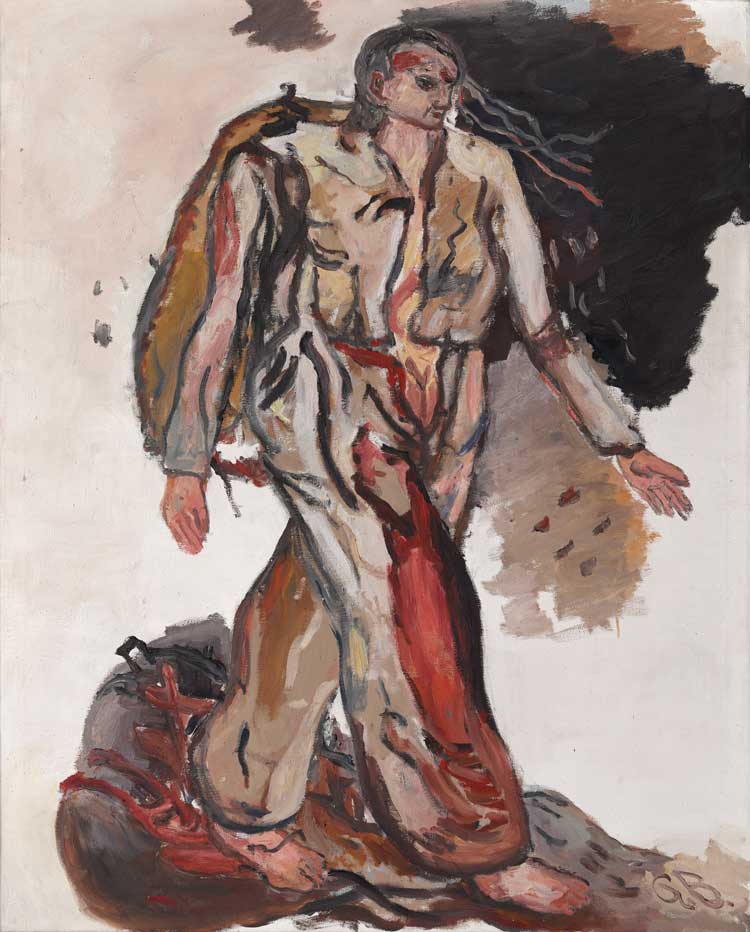

B.j.M.C. – Bonjour Monsieur Courbet, 1965. Oil on canvas

162 x 130 cm. Collection Thaddaeus Ropac. © Georg Baselitz 2021. Photo: Ulrich Ghezzi. Courtesy Collection Thaddaeus Ropac London, Paris, Salzburg, Seoul.

The choice to follow from early to later works may hardly be noticed, as there is a clear continuity through the artist’s career. The destruction he mentions, for example, was there from the beginning. Even in terms of style, from the first to the last painting, he stays faithful to deformation and brutal strokes. To them, Baselitz adds his gradual discoveries of art history and literature, from Edvard Munch, to whom the exhibition dedicates a special room with devilish figures, to Gustave Courbet, Joseph Beuys and Marcel Duchamp, to name just a few.

The very first painting, G Antonin from 1962, is dedicated to the French writer Antonin Artaud, known for his approach to mental illness as well as to suffering: a distorted human figure in pink over a dark background with rough brush strokes. The same colour palette will remain for the next few paintings, displaying his early work. None of them is small, but they are not yet as large as those that will later become one of Baselitz’s trademarks.

,-1963-64.jpg)

Georg Baselitz. Oberon (1st Orthodox Salon 64 – E. Neizvestny), 1963-64. Oil on canvas, 250 × 200 cm. Städel Museum, Francfort-sur-le-Main. Acquired in 2010 thanks to a donation from Dorette Hildebrand-Staab. © Georg Baselitz 2021. Photo © Städel Museum – ARTOTHEK.

The next room displays two remarkable works. The first, Oberon (1963), is a disturbing self-portrait in which not one but four alien-like, spectral faces seem to observe us. The other is a violent sequence of smaller sketch-like paintings inspired by works by Géricault, Rembrandt and Soutine, each of which displays a fragment of wounded, mutilated feet resembling pieces of flesh. Still in the same room, The Naked Man (1962), depicting a man with a long, erect penis, hangs next to The Hook, a strange, non-anthropomorphic form that may be a penis. Following their first exhibition, in 1963, Baselitz faced a lengthy trial for allegedly infringing moral boundaries after the Berlin authorities confiscated The Naked Man and another painting, The Big Night Down the Drain. Many other scandals would follow.

Georg Baselitz. The Naked Man, 1962 (left) and The Hook, installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

By this time, Baselitz was living in West Berlin, after having left his hometown, Deutschbaselitz, whose name he took, and having been expelled from the Academy of Art in East Berlin for a lack of “socio-cultural maturity” when his work drew on that of Picasso. At this point, he had spent most of his lifetime under authoritarian regimes, the Nazis and the German Democratic Republic.

Georg Baselitz. Die große Nacht im Eimer (The Big Night Down the Drain), 1962-63. Oil on canvas, 250 x 180 cm. Museum Ludwig, Cologne. Gift from the Ludwig Collection, 1976. © Georg Baselitz 2021. hoto Jochen Littkemann, Berlin.

In 1965, he spent a six-month residency in Florence, where he became interested in the 16th-century mannerist artists, who opposed the strictly academic and symmetric forms of the Renaissance. The result was Heroes, a set of works depicting ragged, wandering soldiers, contrasting with the social realism iconography of his childhood memories. Two other paintings in the same room demand visitors’ attention: Fixed Idea (1965), a hallucinogenic mix of human and plant, and The Poet, in which a Christ-like figure with (again) a disproportionately sized phallus lies on a red web.

-1966.jpg)

Georg Baselitz. Der Dichter (The Poet), 1965. Oil on canvas, 162 x 130 cm. Private collection, Hamburg. © Georg Baselitz 2021. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin.

The following set of works introduces new techniques: fragmented figures of peasants. Colour and scale are different here: blue and green, for example, were hardly seen before. Also, non-human forms, such as dogs, birds and trees, appear for the first time at the exhibition.

It is at this point that we come to the first “upside down” character, The Man by The Tree (1969). “The hierarchy of sky above and ground down below is in any case only a pact that we have admittedly got used to but that one absolutely doesn’t have to believe in,” said Baselitz, referring to what would become his most notorious trademark. But, before it becomes dominant, Baselitz undergoes a period where black, white and some red in freer strokes build almost abstract paintings, experiments that would show results in his later work.

Georg Baselitz. Die Mädchen von Olmo II (The Girls of Olmo II), 1981. Oil on canvas, 250 × 249 cm. Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris. © Georg Baselitz 2021. Photo © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI B. Prévost. Dist. RMN-GP.

By the turn of the next corridor, when the exhibition starts to head back towards the exit, the visitor will likely have the feeling of experiencing its climax. A set of larger, more coloured works now prevails. In the first room, the world is hot, in vivid yellow and orange, and its inhabitants are now all upside down, as, for example, in The Girls of Olmo II (1981). Here, too, is Baselitz’s first sculpture, Model for a Sculpture (1979-80), inspired by African art and originally created for the West German pavilion at the 1980 Venice Biennale, with rough grooves and painting. In the next room, another provocatively reproduces the gesture of the Nazi salute.

Georg Baselitz. Modell für eine Skulptur (Model for a Sculpture), 1979-80. Linden wood and tempera, 178 x 147 x 244 cm. Museum Ludwig, Cologne. Loan from the Peter und Irene Ludwig Stiftung, 1985 © Georg Baselitz 2021. Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln, Walz, Sabrina, 2001, rba_c015132.

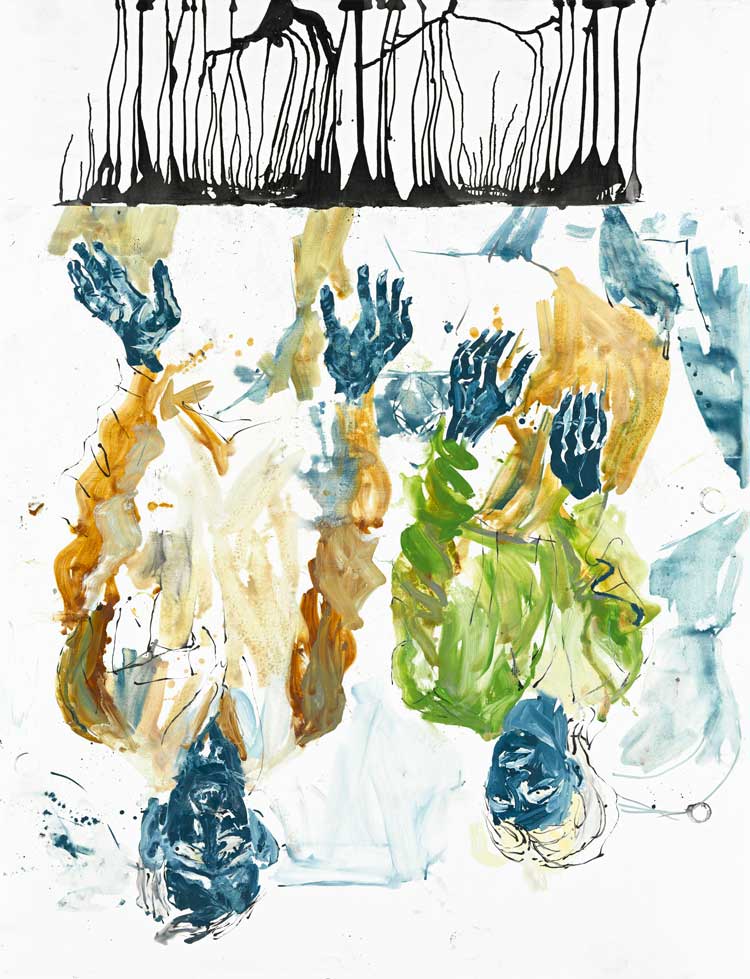

Next, a series of paintings originally shown at the Zeitgeist (Spirit of the Time) exhibition in 1982 brings hanging or floating bodies on canvases where yellow and red create fields of colour within dark, sombre pictures.

Memories from both the first world war and the authoritarian regime under the Soviet Union were frequent motifs in Baselitz’s work, as in the sculptures Women of Dresden (1990), again in yellow, and the later Russian Paintings, including a polemic use of the swastika in Paul’s Dog (2008).

By this time, the canvases have become much larger, so much so that they are created from the ground. And abstraction became increasingly dominant from the 1990s on. Grids, blobs, entangled lines and drops (a reference to pointillism, a forbidden technique during the Soviet regime, which Baselitz had also used in the 1960s Heroes series) are mixed up with increasingly dehumanised bodies.

Georg Baselitz. In der Tasse gelesen, das heitere Gelb (Read in the Cup, the Cheerful Yellow), 2010. Oil on canvas, 270 x 207 cm. Private collection, Hong Kong. © Georg Baselitz 2021. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin.

Figuration reappears during the 2000s, when the artist revisits, reinterprets and transforms some of his earlier works. An example is Modern Painter (Remix) (2007), which recreates the original from 1966. Even here, the figures float in large empty spaces, either painted in white or sometimes in crude canvas. With the same mindset, Read in the Cup, the Cheerful Yellow (2010) “updates” Bedroom (1975), a double portrait of the then younger couple Baselitz and his wife, Elke. Colder and diluted colours are chosen for this later work, replacing the pink skin tone of his earlier pieces.

The piece prepares the visitor for the final room of the show. In much less figurative works, Baselitz reflects on ageing. Figures are here remains of figures. Spectral forms and disappearing silhouettes over dark-coloured backgrounds covered with extra layers of ink are all that remains of the bodies always centrally present at the painter’s work. Gold is a new tone in his palette. The almost lyrical Springtime at the Black Mountain Lake (2020) is striking for being the first and only work to use collage (nylon tights over oil) as technique.

Georg Baselitz. Hibernation, 2014, installation view, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 20 October 2021 – 7 March 2022. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

Central to this last room, Hibernation (2014) is a huge horizontal bronze cast created from a matrix of wood that looks like a gigantic bundle of charcoal sticks bound by hoops carved out of the same material. The sculpture evokes another one, the nine-metre tall Zero Dom (2015), which is currently in front of the Institut de France, facing the Seine, where it will remain for the duration of Baselitz’s exhibition at the Centre Pompidou.

Zero Dom (Zero Dome), 2015. Patinated bronze, 301.5 x 163 x 151 cm. Private collection. © Georg Baselitz 2021. Photo: Jochen Littkemann, Berlin.