Agata Słowak: Time Is Love, installation view, Fortnight Institute, New York, 2023. Photo: Jason Mandella. Courtesy of the artist, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, and Fortnight Institute, New York.

Fortnight Institute, New York

24 May – 24 June 2023

by HATTY NESTOR

Polish artist Agata Słowak’s exhibition Time Is Love, at the Fortnight Institute in New York, undoes and reimagines the body through gender, mythology and fantasy, where figures are vehicles of desire and empowerment. Women are usually the central focus in Słowak’s paintings, and they are often depicted as unleashing physical acts of subversion and domination. Across painting, textiles, and sculptures, her uncanny depictions of the body sit between the real and imagined, and at the heart of the work is a confrontation with exclusion and subordination. Słowak’s canvas becomes the playground for a circus of feelings and a space for dark desires – from madness to sexuality and magic. Through enduring questions of mortality and the body, Time Is Love prompts us to ask how desire has been represented throughout a predominantly patriarchal historical canon of painting.

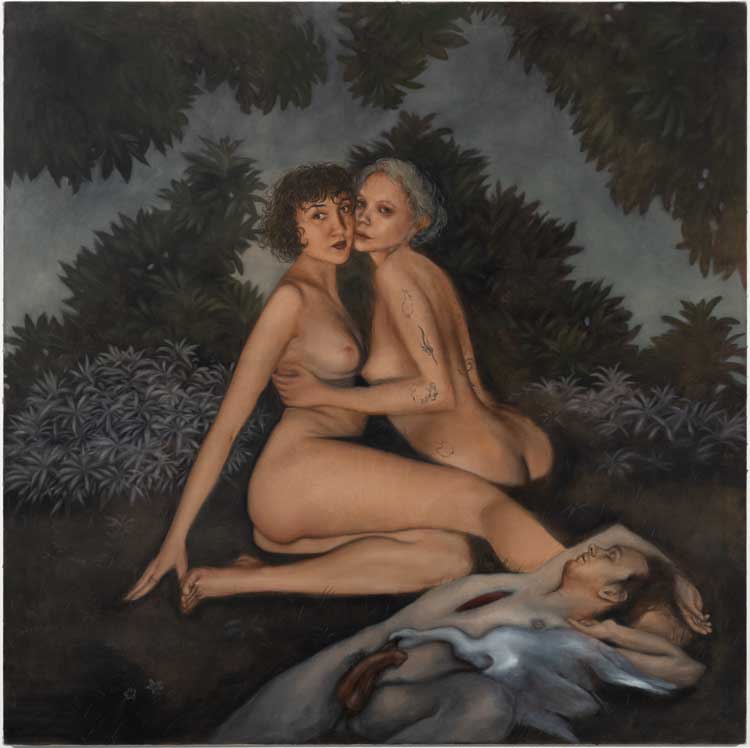

Agata Słowak, Łabędzi Śpiew (Swansong), 2022. Oil on canvas, 55 1/8 x 55 1/8 in (140 x 140 cm). Courtesy of the artist, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, and Fortnight Institute, New York.

Słowak was born in 1994 and has been painting throughout the last decade. Time Is Love is subtle and tantalising – there is an element of surrealism and dadaism in her works, a feeling that her paintings speak to a history of strangeness and absurdity of the body. She also often features as the main protagonist of her paintings – there is an uncanny resemblance to her appearance. Nine of her paintings are mounted on the white gallery walls, the gaze of each figure filling the space with presence and unease. The back wall features Swansong (2022), a large-scale oil on canvas painting of two naked female figures embracing in a woodland setting, while, beside them, a dead man lies unclothed with a slit in his chest, a swan laying near his penis. The ambivalence in this scene sets the tone for Time Is Love, placing the viewer in a world of desire and destruction, love and pleasure.

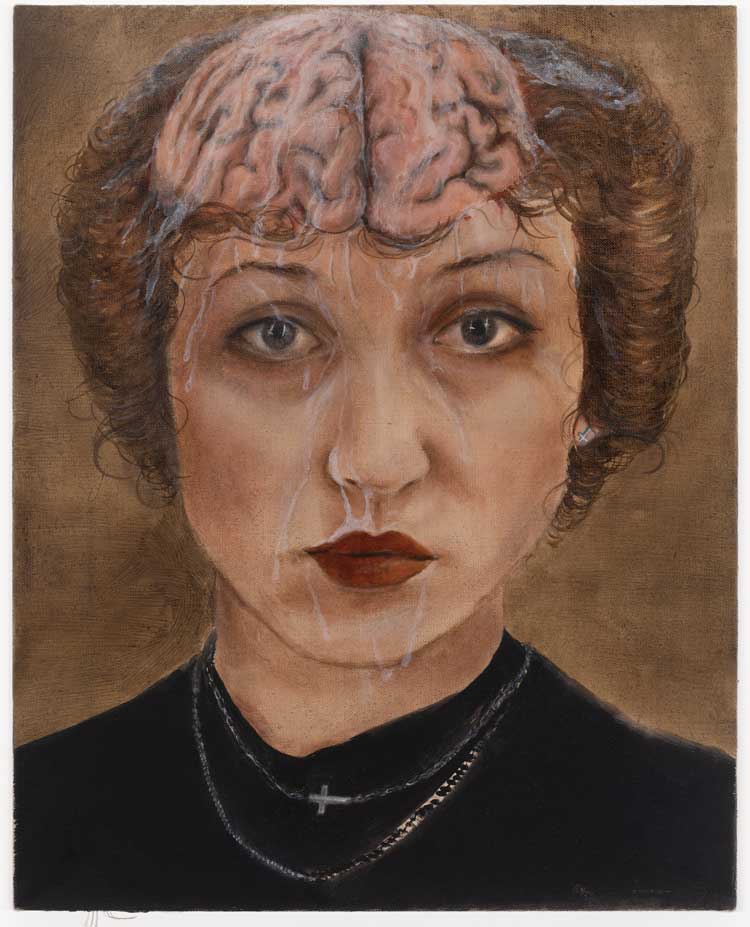

Agata Słowak, Sperma zalała mózg (Sperm Flooded the Brain), 2023. Oil on canvas, 19 3/4 x 15 3/4 in (50 x 40 cm). Courtesy of the artist, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, and Fortnight Institute, New York.

Swans, frequently associated with transformation and purity, appear often in Słowak’s work. Similarly, other iconographies in her work – the phallus, the splitting of the body and the exposure of a woman’s mind – speak to tropes of oppression within mythology, sexuality and psychology. (Freud, for instance, attributed the domination of the phallus to that of masculine powers; he also would argue that, symbolically, nobody can possess it.) There is also an undoing of psychological space in Słowak’s other paintings. In Sperm Flooded Brain (2023), the artist depicts herself without hair, her brain exposed to the air and covered in sperm. The exploration of sexuality here is communicated through this stark image – the mixing of male ejaculation with a woman’s mind. It is easy to draw conclusions about what the works mean, but it is the ambivalence of their narrative that makes the paintings uncanny and mesmerising.

Agata Słowak: Time Is Love, installation view, Fortnight Institute, New York, 2023. Photo: Jason Mandella. Courtesy of the artist, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, and Fortnight Institute, New York.

The expressions of Słowak’s figures tend to be stern yet playful, where binaries and opposites are always found within the paintings. Her palette is subtle and subdued, often sitting between pale pinks, murky greens and dark greys. However, on occasion, a monster or object is cast in electric red. On the left-hand wall, several paintings feature closeups of bodies with phallic objects and monsters. For instance, Penis Constellation (Kitty’s Paw), 2023, shows the thighs and stomach of a man, his erect phallus with a hook through it like a piece of fish bait being pulled upwards, and small fish with hooks through them swimming in the same direction, up the body. A cat’s paw appears to be dabbing at a fish on the figure’s hip, and the hand of a woman wearing nail varnish rests on the opposite hip. The word “kitty” in the title also could be perceived as the name of a pet. Caught in a strange poetic realm of animal-human relations, there is a sense that the hierarchy between us and them is equalised.

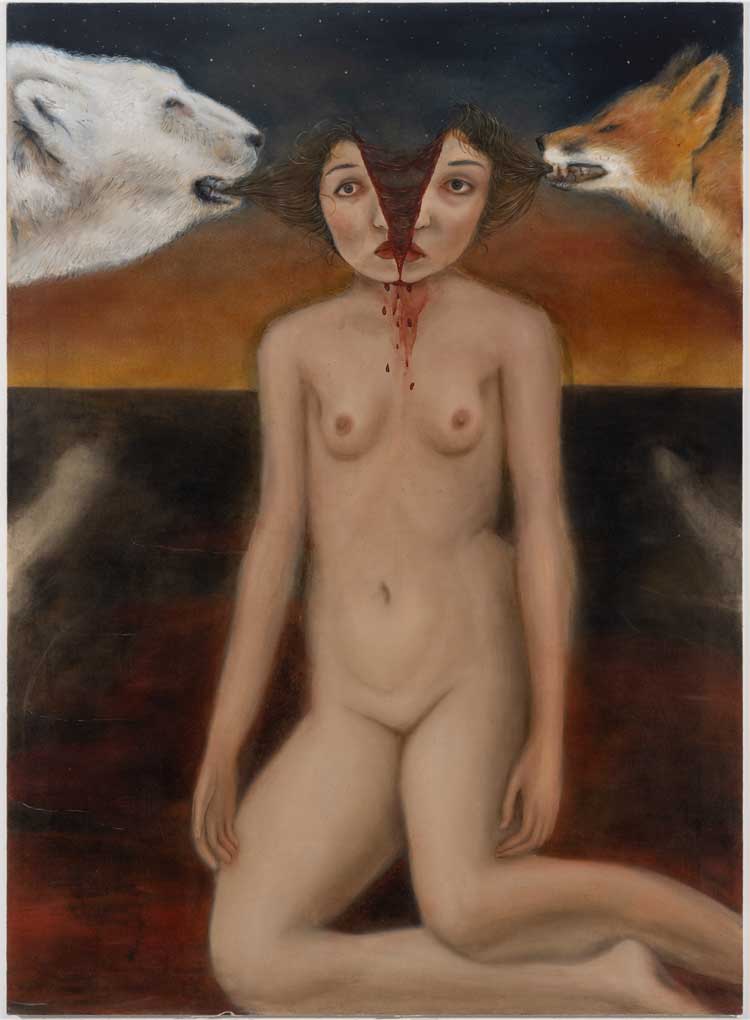

Agata Słowak, Sytuacja z niedźwiadkiem polarnym i liskiem (Situation With Polar Bear and Fox), 2023. Oil on canvas, 43 1/4 x 31 1/2 in (110 x 80 cm). Courtesy of the artist, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, and Fortnight Institute, New York.

The scenes depicted in Situation With Polar Bear and Fox (2023), however, splits identity in two. Again, Słowak depicts herself: her head is sliced in half as she poses full-frontal to the viewer, a fox and a polar bear on either side of her head, as if they are pulling her apart with their teeth. The setting is nondescript and, in Słowak’s ambiguous world, the human-animal relations are placed in a surreal, albeit dangerous realm where animals can deconstruct us, unravel us and reveal our innate vulnerabilities. If the “splitting” of the psyche allows for different emotions and responses, then Słowak’s splitting of herself shows the effect of animals on the human mind.

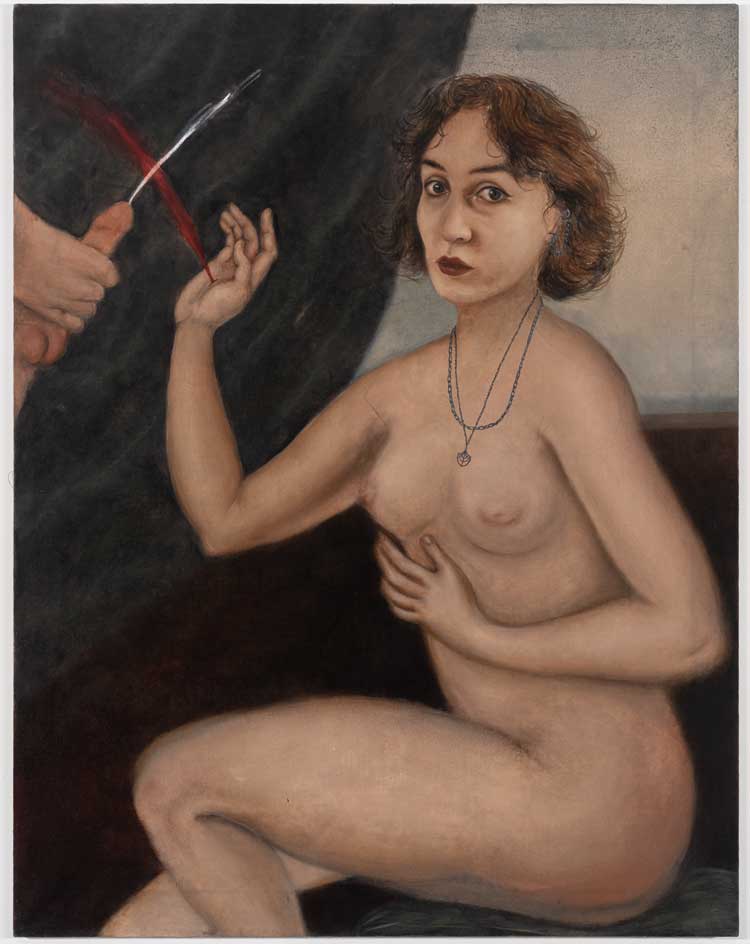

There are hints of stylistic qualities in Słowak’s painting Self-portrait with Sperm and Blood Crossing (2023) reminiscent of the woman in Édouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1862-63), or Amedeo Modigliani’s discerning female portraits from the early 20th century. The brushstrokes have a similar aesthetic sensibility, particularly when Słowak is portraying the natural world. Yet often in these works, the female nude takes centre stage, emulating radiance and self-empowerment to comment on wider socio-political and racial tensions. However, Słowak’s paintings also question magical realism: are these real-life women, or imaginary? Are the monsters who sit among them from nightmares or mythology?

Agata Słowak, Autoportret z krzyżowaniem spermy i krwi (Self-portrait with Sperm and Blood Crossing), 2023. Oil on canvas, 35 3/8 x 27 1/2 in (90 x 70 cm). Courtesy of the artist, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, and Fortnight Institute, New York.

Her titles hold the clues, and in turn, signify something else: by repetitively referencing sperm and blood, reproduction and sex are woven through all the paintings, making the muted sense of desire in these older master’s paintings feel more controlled and of the present. Słowak brings these stylistic qualities into the present. In this way, there are similar moments of reference to the modern day, such as the Nike trainers in Bad Fetus (2023), which restate the historic tonalities of Słowak’s paintings in contemporary society. In this visceral and alarming painting, the woman’s hand draws out a dark red creature (the foetus) – a stark and declarative reminder of the experience of abortion. At a time when women’s rights are increasingly under threat, this painting bravely symbolises what has not always been readily available to women and remains inaccessible in many parts of the world.

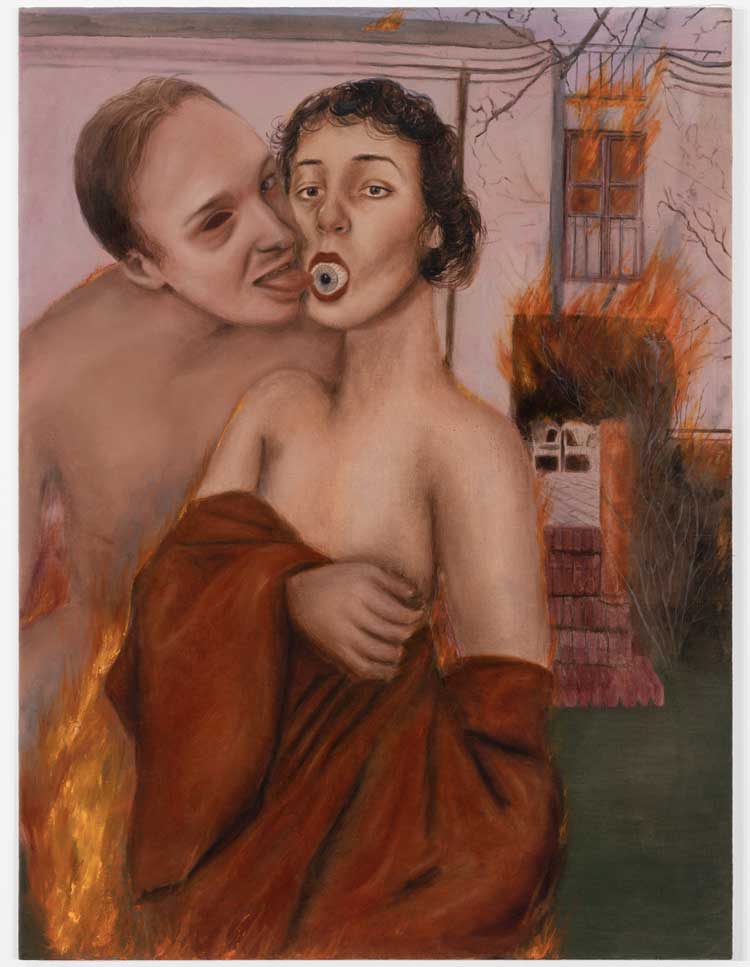

Agata Słowak, Byclo Ci Zimno w Moim Cieniu (You Were Cold in My Shadow), 2023. Oil on canvas, 31 1/2 x 23 5/8 in (80 x 60 cm). Courtesy of the artist, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw, and Fortnight Institute, New York.

What unifies Słowak’s work is her ability to touch on enduring questions of gender, the monstrous and desire, encapsulating the strange and uncanny experience of intimacy and embodiment across generations. In her figures, we enter an affective space of feeling and abjection – at times joyful, but often surreal. But in gazing into the figures’ eyes, a sense of relatability still comes forth. Finally, viewing You Were Cold in My Shadow (2023), at the end of the exhibition, the power relations of men and women are articulated in an uncomfortable scene. A woman with an eye in her mouth looks perplexed as a man embraces her from the side – his face almost clown-like, uncanny. The two of them are caught in a contradiction of intimacy and distance, neither seeming at ease or fully present with the other.

Słowak’s work never lets up in its ability to touch on the visceral and complex experiences of existence. Bodies break, fold, interact and stand alone – nuanced in their ability to exist alongside one another. By dissolving the male gaze on the female body, these paintings astutely respond to questions of gender, identity and sexuality. Słowak reimagines our subconscious desires and generalisations and how we view women in painting today. It is the facility to illustrate these tensions that shows Słowak at her best. Never compromising, unflinchingly strange, these paintings reimagine not just who women are, but how they are perceived.