-Centre-Pompidou,-MNAM-CCI_Janeth-Rodriguez-Garcia-(11).jpg)

Installation view, Vera Molnár: Speak to the Eye, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2024. Photo: Janeth Rodriguez-Garcia MNAM-CCI.

Pompidou Centre, Paris, France

28 February – 26 August 2024

by JULIET RIX

Planned to celebrate Vera Molnár’s 100th birthday in January 2024, this exhibition became the first lifelong retrospective of her work and the last show with which she would be personally involved, when she died in December 2023.

It starts a little unpromisingly with a shaky line across a long piece of paper. This earliest work, dating from 1946 is called Collines (Hills). It also looks very like a trace from a mechanical or digital device, a pertinent glimpse of things to come from this pioneer in the use of computers and algorithms as tools for the generation of art.

Vera Molnar. OTTWW, 1981-2010. Installation view, Vera Molnár: Speak to the Eye, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2024. Photo: Juliet Rix.

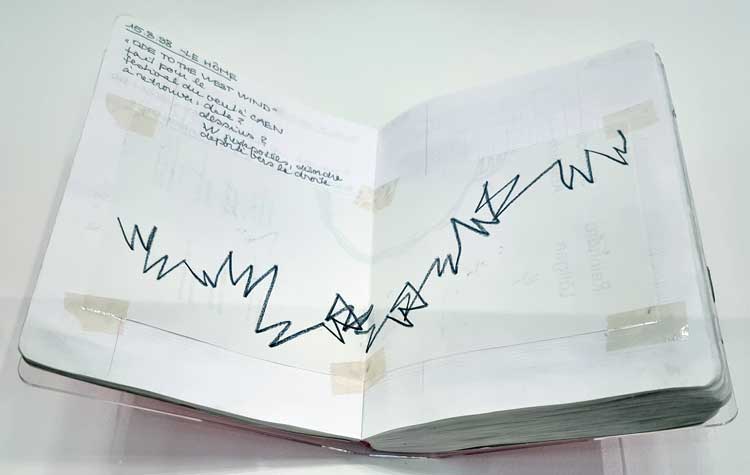

Born in Budapest, Molnár attended the Hungarian University of Fine Arts before moving to Paris in 1947 and making her life in France. The hills of her Transdanubian childhood, however, remained a touchstone throughout her life and hill-like (and trace-like) images play a significant role in this show. One of the most engaging is OTTWW (1981-2010), an abstract oscillation of black cord over dark nails, like a confused Alpine landscape or overlapping soundwave. Begun as a dialogue with the letter W, it was inspired by Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ode to the West Wind (hence the title) and created for a wind festival in Caen, Normandy. Designed via an algorithm invented by the artist, there is something intriguing and playful about this line squiggling its way along a white wall, turning a corner and squiggling off along the next.

Molnár likes to play. Most of her work is process on paper rather than clear conclusions. She plays with geometry and form, adjusting it over and over to see where it takes her. She has no interest in representation. Since her 1946 Trees, in which she reduces the trees to their geometric essence (sometimes containing them within rectangles), she says, barring a few “relapses” up to 1949: “The idea never again occurred to me to represent nature in any form whatsoever … [and] I have the impression that everything I’ve done since stems directly from these few sketches.”

Vera Molnár. Quatre Éléments Distribués au Hasard, 1959. 75 x 75 cm. Collection Pompidou Centre, Paris. © Adagp, Paris, 2024. Photo: Georges Meguerditchian - Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Dist. RMN-GP.

Influenced by Matisse before she left Hungary and then by the Paris avant garde, as well as by the geometry and colour systems of the Dutch De Stijl movement, Molnár explored shape, line and colour. Clearly influenced by Piet Mondrian – witness Quatre Éléments Distribués au Hasard (1959) – she nonetheless makes the ideas her own. She consciously liberated herself from his obsession with primary colours for instance to produce Icône (1964), a gilt line at the centre of a gleaming sunset-orange square, an abstraction of golden religious icons.

Vera Molnár. Icône, 1964. Oil on canvas, 73 x 73 cm. Collection Centre Pompidou, Paris. © Adagp, Paris, 2024. Photo: Bertrand Prévost - Pompidou Centre, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP.

At the end of the 1960s, Molnár began to use algorithms to “generate” work – either manually or with the help of a computer. Computers were then rare and huge, and she paid by the hour to use a university computer in Paris. She had, however, already developed what she called her machine imaginaire (imaginary machine), manually using mathematical formulae to guide the creation of variations on a theme.

Vera Molnár. A la Recherche de Paul Klee (Seeking Paul Klee), 1969-70. Ink on paper, 70 x 70 cm.

Collection Frac Bretagne © Adagp, Paris 2024 Photo: Hervé Beurel.

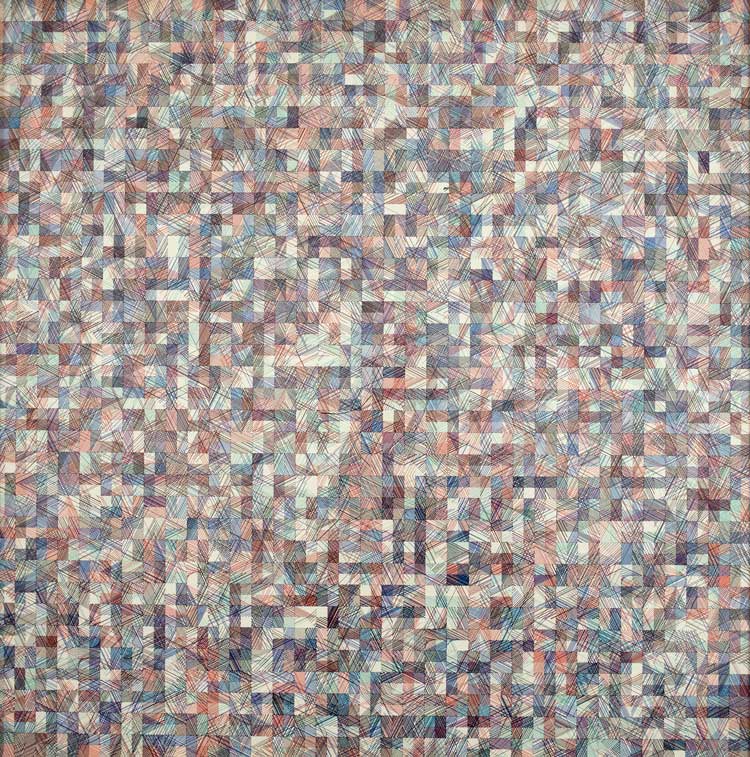

In A la Recherche de Paul Klee (Seeking Paul Klee, 1969-70), her starting point is Klee’s 1927 Variations (Progressive Motif), a chequerboard of squares filled with a variety of vertical, horizontal and diagonal lines, with some background colour. Molnár created variations on this theme – a series of algorithmic drawings introducing different disruptions to her starting point. She is interested in abstraction and organisation of form, but also in what happens when an element of disorder is introduced.

Her work is more intellectual than emotional, though that doesn’t preclude humour and inventiveness. Molnaroglyphs (1977-78) is an enjoyable example. Starting with a page of squares, she joins them, divides them, spaces them, squeezes them, flattens them and shakes them, rejoining them in new ways before shaking them again until they lose all individual integrity, becoming entirely an interplay of lines.

Vera Molnár. Diary page. Installation view, Vera Molnár: Speak to the Eye, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2024. Photo: Juliet Rix.

For the devotee, there is much to delve into in this exhibition with several cases of what the curators call her diaries. More like sketchbooks, these are full of sketches, notes and cutouts, some the first jottings of ideas for the works that we see on the walls.

Vera Molnár. Perspective d’un Trait (Perspective of a Line), 2014-19. Installation view, Vera Molnár: Speak to the Eye, Pompidou Centre, Paris, 2024. Photo: Juliet Rix.

Her later work is less interesting, perhaps because by then it no longer seems original. La Vie en M (Life in M) from 2023, made for this exhibition, is a case in point – a fun bit of graphic art playing on her initial. The show ends, however, with a previously unseen piece of sculpture right outside Molnár’s usual practice. It harks back to the work of an earlier Hungarian artist – whose work she was denied knowing in her native country because he was then deemed degenerative – master of light sculpture László Moholy-Nagy. Molnár’s Perspective d’un Trait (Perspective of a Line), 2014-19, is a three-dimensional presentation of a 2014 drawing. Constructed in stainless steel and anodised aluminium in collaboration with an industrial firm, light plays through its grills in different ways as the viewer moves. She kept her spark of exploratory interest to the last.