Vincent van Gogh, Olive Trees, 1889 (detail). National Galleries of Scotland.

Tate Britain, London

27 March – 11 August 2019

by NICOLA HOMER

“Yellow flowers – brimming with sun in a pot” was how the great short-story writer Katherine Mansfield remembered Van Gogh. In a letter in 1921, she talked about the freedom that she discovered in his paintings. This illustrates the enthusiastic reception of his work in avant-garde art circles of the early 20th century. A key moment arrived in 1910, with the staging of the exhibition Manet and the Post-Impressionists, organised in London by the English art scholar Roger Fry.

Christopher Wood, Yellow Chrysanthemums, 1925. Oil paint on canvas, 61 x 51 cm. Mr Benny Higgins & Mrs Sharon Higgins.

The selection of works took its cue from the German critic Julius Meier-Graefe’s Modern Art (1908). Fry coined the term “post-impressionism”, seen in a belief in colour as an emotional signifier of meaning. The exhibition was a turning point in British culture, for its power to shock the public, as it showed the modern styles of Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh together for the first time in Britain. In response, Virginia Woolf, a friend of Mansfield who, like Fry, was part of the Bloomsbury set, wrote, “on or about December 1910, human character changed”.

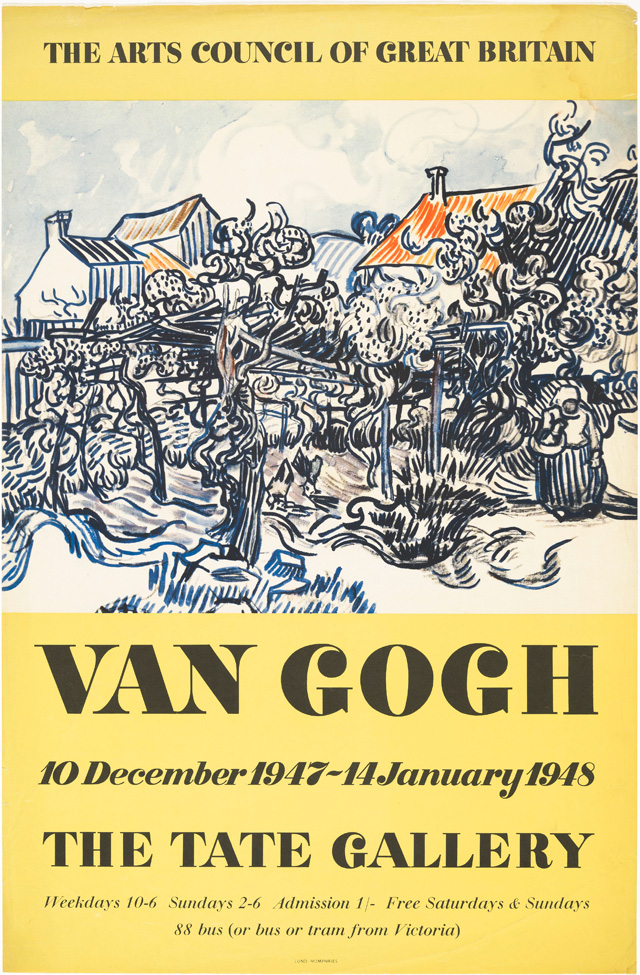

Vincent van Gogh exhibition poster, Tate Gallery, 1947. © Tate, 2018

This is the first Van Gogh exhibition to be held at the Tate since 1947. The postwar show travelled to Birmingham and Glasgow, where “Van Gogh’s dazzling colours cheered the war-torn cities”, according to a wall text in the final gallery. At the heart of the exhibition, you can explore the influence of Van Gogh on young British artists and see a representation of his artworks in Manet and the Post-Impressionists. A portrait by Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell, depicting Fry, signposts the inspiration that British painters drew from the decorative colour of Van Gogh.

Jacob Epstein, Sunflowers, 1933. Watercolour and gouache, 55.9 x 43.2 cm. Private collection. © The estate of Sir Jacob Epstein.

One gallery looks at how the Camden Town painter Harold Gilman and colourist Matthew Smith applied vibrant hues to their own versions of his subjects. Another is a curatorial paean of British artists’ responses to Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, including floral paintings by Jacob Epstein, Christopher Wood and Samuel Peploe.

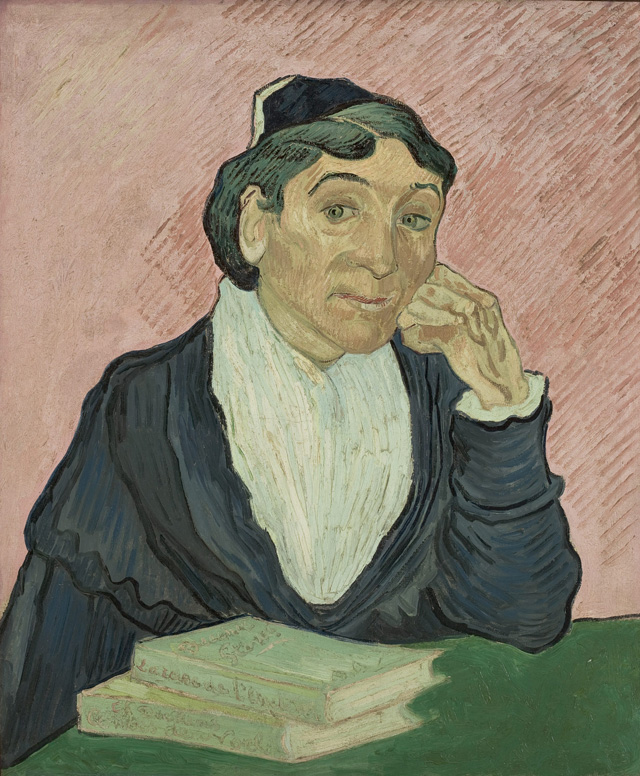

Vincent van Gogh, L’Arlésienne, 1890. Oil paint on canvas, 65 x 54 cm. Collection MASP (São Paulo Museum of Art)

Photo credit: João Musa.

At the beginning, you will find a delicately coloured portrait of Van Gogh’s absent friend, who ran a train station cafe, in The Arlésienne (1890): the woman has a pensive look as she sits at a table with a talisman of books: Charles Dickens’s Christmas Stories and Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Almost tangibly, this painting suggests that Van Gogh was remarkable in being a post-impressionist, whose ideas were cultivated by 19th-century English literature. While he had read Dickens’s stories before he moved to London, in May 1873, to work at the Covent Garden office of Goupil & Cie, which had a flourishing business in art reproduction, for the next three years he absorbed much more British culture. Van Gogh visited the British Museum, Dulwich Picture Gallery, the National Gallery and the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition.

Vincent van Gogh, The Prison Courtyard, 1890. Oil paint on canvas, 80 x 64 cm. © The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

On show are paintings by three English artists, who appear on a list of more than 50 artists whom Van Gogh particularly liked, in a letter written in January 1874: George Henry Boughton, John Everett Millais and Richard Parkes Bonington. When he became a lay preacher, after being an art dealer and a teacher, he based his first sermon on Boughton’s God Speed! Pilgrims Setting Out for Canterbury (1874). Van Gogh admired the bleakly beautiful landscape Chill October by Millais in his letters. He owned the lithograph A Road by Jules Laurens, after Bonington’s A Distant View of St-Omer (c1824), and kept the print until the end of his life. In a letter to his brother Theo, he said A Road reminded him of a landscape in George Eliot’s Adam Bede, which he read in 1875. With a horizon dotted with people and a great expanse of sky, A Distant View of St-Omer appears next to his Bleachery at Scheveningen (1882). A wall text reads: “Van Gogh was moved by the suggestion of a human story in Bonington’s road through a landscape.”

In the insightful catalogue, the lead curator, Carol Jacobi, writes: “Most importantly, British culture informed Van Gogh’s thoughtful and egalitarian appreciation of the drama of the everyday explored in Dickens and Eliot, Pre-Raphaelite and social realist artists that departed from picturesque representations of the poor to present us with modern working men and women in both urban and rural settings.”

Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night, 1888. Oil paint on canvas, 72.5 x 92 cm. Paris, Musée d'Orsay. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski.

What is fascinating about this exhibition is that it reveals the influence of social realist artists on Van Gogh. He was particularly drawn to the illustrated newspaper The Graphic, for its hard-hitting visual journalism – Hubert von Herkomer’s Heads of the People (1875) was a touchstone for his dignified portraits that anticipate The Arlésienne. Van Gogh admired Gustave Doré’s prints of London scenes and collected Luke Fildes’s Houseless and Hungry (1869), an image of a night shelter, on display in the exhibition. This led to a commission for illustrations of The Mystery of Edwin Drood by Dickens, such as The Empty Chair (1870), inspired by the novelist’s empty chair, which presents a clear analogy with a vignette of a chair portrait of Gauguin by Van Gogh (1888). Yet while an interesting narrative unfolds in relation to how he was sustained by the social conscience of Victorian artists, a viewing of his great works suggests that he was a truly European painter.

Vincent van Gogh, Shoes, 1886. Oil paint on canvas, 38.1 x 45.3 cm. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation).

William Nicholson. Miss Jekyll’s Gardening Boots, 1920. Oil paint on wood, 32.4 x 40 cm Tate © Desmond Banks.

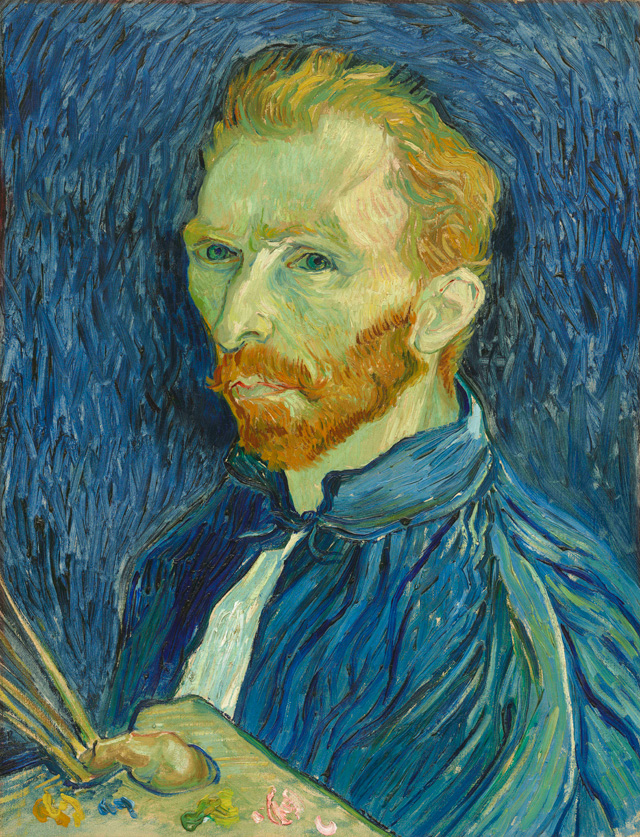

Full of resonance for philosophers is the Shoes, from a pivotal time in his career in Paris in 1886 – when Van Gogh became an impressionist in search of an alternative to naturalism – before he settled in Arles in France in 1888, when he created his crepuscular vision of Starry Night and his monumental Trunk of an Old Yew Tree, which are stand-out pieces of this exhibition. The expression of the artist’s face, set against a backdrop with the colour of the deep blue sea, is worth catching in his Self-Portrait (1889), created in a hospital in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

Vincent van Gogh, Self-Portrait, 1889. Oil paint on canvas, 57.2 x 43.8 cm. National Gallery of Art, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. John Hay Whitney.

The haunting image is a short walk away from the final gallery. There you will find a brilliant tribute in paintings from Francis Bacon’s series, Study for Portrait of Van Gogh (1957), inspired by the Dutch artist’s self-portrait on a road through the same landscape: The Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888). This is a memorable end to an excellent exhibition, which conveys the inspiration and solace that modern artists in Britain discovered in the work of this remarkable post-impressionist.

-Estate-of-Francis-Bacon.jpg)

Francis Bacon, Study for Portrait of Van Gogh IV, 1957. Oil paint on canvas, 152.4 x 116.8 cm. Tate © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. DACS, London.