by JULIET RIX

Tim Clark retired as head of the Japanese collection at the British Museum at the end of last year and is now a research fellow there, focusing on specific projects, particularly Late Hokusai: Thought, Technique, Society. His long service to Japanese art was recognised this April when the Japanese government awarded him the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette (旭日小綬章, Kyokujitsushōju-shō) for his contribution to the understanding of Japanese culture in the UK.

Having developed an interest in Japan as a child, in his early teens he was given a Japanese print by friends of his parents. His interest grew from there and, wanting to be able to read the writing in the prints, Clark studied Japanese at Oxford before starting a PhD at Harvard. He did not complete the PhD but, instead, spent three years studying in Japan, returning to the UK just as the British Museum was establishing new Japanese galleries. He was quickly recruited, and stayed for 32 years.

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). Cats and hibiscus. A standoff between two cats, with hibiscus (fuyō) behind. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Japanese collection he rose to lead comprises 30,000 objects connected with Japan. Clark’s primary interest has long been Japanese prints, drawings and paintings of the Edo period (1600-1868) and the Meiji era (1868-1912), and particularly the work of the artist Hokusai (1760-1849).

The museum already had one of the most comprehensive collections of Hokusai outside Japan before its recent purchase of 103 of the artist’s newly rediscovered drawings brought its holding to more than 1,000 items. Clark is the author or co-author of numerous books and catalogues on Japanese art. He has curated multiple exhibitions, including the museum’s flagship 2017 show, Hokusai: Beyond the Great Wave, which attracted 150,000 visitors and went on to be equally successful in Japan.

To Clark’s astonishment and delight, last year the museum was offered the 103 Hokusai drawings, which are all ink on paper. They were intended to become illustrations for a book entitled The Great Picture Book of Everything, but it was never published. With £150,000 from the bequest of Theresia Gerda Buch, and £120,000 from Art Fund (as well as a £30,000 discount for a public institution), Clark secured the images. The drawings were made in 1829, previously thought to have been a fallow period in the artist’s life after he had a minor stroke and his second wife died, and shortly before he started work on his best-known work, Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (expanded to 46 prints), which includes his most famous image, The Great Wave.

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). India, China, Korea. In six of the group of 103 drawings, the small horizontal page has been divided vertically into three. Within each division are drawn typical inhabitants of lands in East Asia, SE Asia, Central Asia, and beyond. Some figures are mythological. Shown here are representatives of India (right), China (centre) and Korea (left). Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Clark spent lockdown in the company of Hokusai, studying the works and helping to put them into the museum’s newly improved Collection Online, which allows anyone to access the images and to zoom in and pan around them in great detail. Studio spoke to him about the artist and the drawings.

Juliet Rix: I have very much enjoyed exploring these images online. Is this also a useful tool for you?

Tim Clark: We revamped the British Museum website during lockdown to produce this more interactive, zoom-in, system. There are about 4.5m objects in there now, and 1.9m images. I’m really enjoying it and finding it very useful.

These Hokusai drawings were intended for a book, so they were always meant for a mass audience. That never happened, but now, thanks to web technology, we are sending them out even further than Hokusai could have conceived. It’s been the perfect lockdown project for me, teasing out the inscriptions and the meanings of this set of drawings – which is a picture encyclopaedia as well as a picture book. The drawings have characters written on them and sometimes they give different versions of how you might name what is in the picture. The primary enjoyment is, of course, Hokusai’s amazing style, but there is an educational intent there as well, a desire to catalogue the universe.

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). Mei Jianchi avenges himself on his enemies with the sword. A scene from a legend of the ancient Spring and Autumn period of Chinese history. Chi (Mei Jianchi) is the son of husband and wife swordsmiths. His severed head, with a sword made by this father Ganjiang in its mouth, jumps out the cauldron in which it was supposed to be boiled down to become unrecognisable. A related rough sketch by Hokusai is in the ‘Curtis’ album (no. 8) at the Bibliothèque nationale, Paris. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

JR: The Great Picture Book of Everything is a wonderful title.

TC: It is a fantastic title and it’s typical for Hokusai and his increasing ambition as he gets older. He was 70 when he did these drawings and in his last three decades, from 60 to 90, he had a very strong notion of what he wanted to achieve artistically – in this case literally to draw everything. In a sense, he is very modern. He was the most famous Japanese artist of his period and he was aware of getting the Hokusai brand, the Hokusai style, out there. So were his publishers, who put his name into the titles of many of their books. He was part of a system that allowed his vision to be put out into society, using the technology of the wood-block print. Prints were pretty inexpensive. There were as many as 5,000, maybe 8,000 impressions from the original block of the Great Wave and the price of a single sheet print got down to just a bit more than a double helping of noodles in a restaurant. If you were in the right place at the right time – a print shop in Edo (Tokyo) in 1831 – and you went without your dinner, you could have your own Great Wave.

JR: How exactly would the newly acquired drawings have been used in the context of the planned book?

TC: These drawings are what we call block-ready – line perfect and intended to be used by the block-cutter. He would have placed them face down on cherry wood, then cut through the back of the drawing to create the printing blocks. So it was expected these drawings would be destroyed, but the payoff is that you produce an illustrated book that is published in hundreds of thousands of copies. Hokusai was extremely exacting about the quality of the reproductions. He wrote to his publishers insisting they employ the top block cutters and sometimes complained when they cut in ways he didn’t like. He was a perfectionist. The block-cutters can’t bring anything to the print that isn’t in the drawing. They are just trying their damnedest to reproduce all the nuances of his brush line. If his drawing is not exciting as a drawing, there is no way that there’ll be energy in the finished print.

JR: Vibrancy is more likely to be lost in the process than gained?

TC: Exactly. And what we’ve got in this set of drawings is the tremendous energy and invention directly from the man’s brush. And more than 100 of them.

JR: This was quite a find. How did you first come across this set of drawings?

TC: I first saw them about a year ago. The dealer, Israel Goldman (who has worked with the British Museum in the past to get great things into a public collection) had purchased them at an auction in June 2019. I hadn’t heard anything about them until he brought them to show me in October. I was flabbergasted, gobsmacked. Since then, I’ve spent most of my time in happy study of these drawings and seeking opinions about them from other scholars and Hokusai experts around the world. The story just gets more and more interesting.

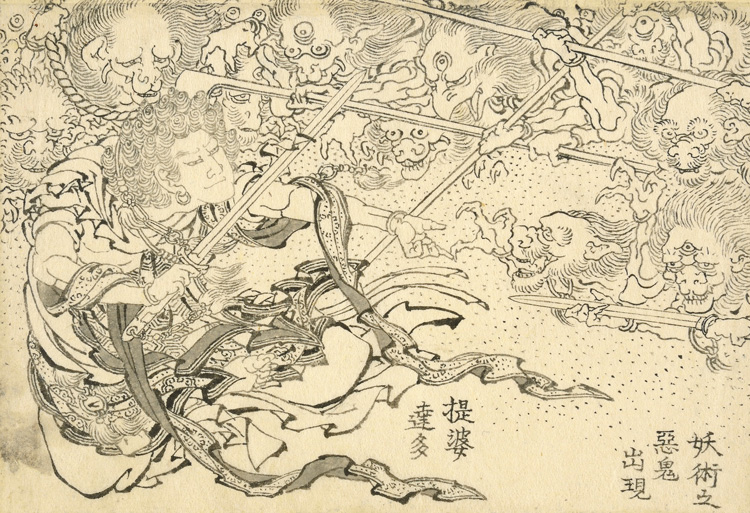

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). Devadatta (Daibadatta), appearance of evil spirits with supernatural arts. Monk Devadatta was by tradition the cousin and brother-in-law of Shakyamuni Buddha. In the Lotus Sutra he was the archetype of an evildoer. Here he holds sway over a variety of grotesque evil spirits. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

JR: What have you discovered?

TC: The title, The Great Picture Book of Everything, is written on page one of the 103, and the way it’s written suggests it is the title of an overarching project of which this is only a part. The second drawing is of two charming figures, an Indian man and a Chinese boy, and it says “India”, “China”. This gives us a clue to one of the main focuses of this particular group of drawings. It is clear that this group has a very close relationship to another group of 178 block-ready drawings in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Very similar in style, and with very similar format, they have some subtitles but there’s no main title or date. So, already, we’re wanting to put these groups together to think what the overall parameters of this grand project may have been and what percentage of the drawings have survived. And now we have a date of 1829, we can also think about where these sit in Hokusai’s life and work.

JR: Where do they sit?

TC: They are key. You can enjoy the drawings without knowing any of this but, for Hokusai, the end of the 1820s is a fairly empty period in his life, full of difficult personal challenges. And it is just a short time before he embarks on the famous Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, the colour wood-block series that includes the Great Wave. These 103 drawings help to fill in an empty part of the biography. Just months after making these drawings, in early January 1830, Hokusai sends a rather desperate letter to his publishers asking for work, saying he’s destitute, has no money, no clothes, barely enough to eat. Although, undoubtedly, he’s laying it on because he wants the work, it is a very serious time for him. I surmise that maybe the great Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji was a project that helped to save his life and career.

JR: Could the failure of the publication of The Great Picture Book of Everything have led to this destitution?

TC: I don’t know. I hope he got an advance. We don’t know why it wasn’t published. Was it too ambitious? Too expensive to produce? Was there a change in taste? It invites comparison with another big book project by Hokusai that was published: the famous Hokusai Manga – 10 books of 30 teeming spreads each, produced between 1814 and 1819, burgeoning with life and all kinds of themes and topics, but not so systematically organised.

The Manga were extraordinarily successful. Maybe The Great Picture Book of Everything was meant to be the same kind of project, but taking it further, stretching beyond the very narrow confines of the world in which Japanese people were living in this period. Foreign travel was prohibited and you were not supposed to leave your town or village without permission. Hokusai is undoubtedly trying to use his extraordinary vision and imagination to open up worlds for captive readers. India and China are the two big themes and he takes us right back to ancient India and the origins of the Buddhist religion. And in the case of China, back to the origins of human civilisation as described in ancient Chinese texts – human beings adopting habitation, agriculture, writing, printing and even the production of alcohol.

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). Yi Di (Giteki) orders the people to use rice juice to brew wine. Yi Di is said to be one of the earliest brewers of rice wine, which he presented to Yu the Great of the Xia dynasty. In this comic scene, men seem to be using the weight of a large rock to squeeze liquor from the rice. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

JR: Like the wonderful drawing of making rice wine?

TC: Yes. It is great isn’t it. The two guys are sitting on a thick pole that seems to be coming out of the rock face, and the way I read it is that they are crushing a bag of, probably, rice grains, and the juice is pouring out at the bottom into this guttering and flowing off to the right, and there’s a rock hanging on the pole for extra weight. Both guys have their ankles wrapped together, pressing down for dear life to stay on the pole. There’s something about the way Hokusai captures these human poses that just brings them to life. This is such an ancient story – ostensibly we are back many centuries BC – and yet Hokusai manages to make it look as if it is happening right in front of you. That is fundamental humanism. People compare it to Rembrandt and I think that is a very good comparison. It has the humanity and everyday accessibility and recognisability of a little sketch by Rembrandt.

JR: Is there any evidence that Hokusai saw anything by Rembrandt?

TC: Sadly, I don’t think so, although Rembrandt drew on Japanese paper and Amsterdam was the centre of Dutch trade with Japan for more than 200 years, from the middle of the 17th century to the middle of the 19th – so through Hokusai’s period. Hokusai did some paintings for the Dutch East India Company, which found their way back to Holland in the 1820s. He may even have had direct contact with the Dutch traders in Edo (Tokyo) who commissioned them, but in writings by popular artists of this period, including Hokusai, we don’t see any transcriptions that look like the names of any artists in Europe.

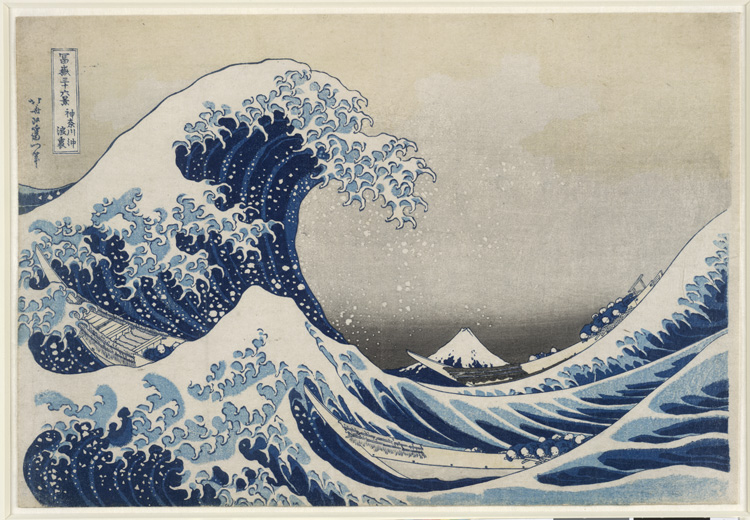

Kanagawa-oki nami-ura 神奈川沖浪裏 (Under the Wave off Kanagawa). Colour woodblock oban print. 'The Great Wave'; fishermen crouching in three skiffs, with towering wave about to crash down on them, Mt Fuji seen low in hollow of wave. Inscribed and signed. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum. 2008,3008.1.JA

There is connection with European art, though, and it’s a really important connection. It’s embedded in the Great Wave print. The deep perspective Hokusai plays with in that image comes right out of European topographical views that were finding their way to Japan. When Hokusai was young, he made some quite slavish copies of European perspective views, but by the time he’s in his 70s, he has absorbed all those lessons and is playing with them in amazing ways. Mt Fuji is the highest mountain in Japan, but he sets up the picture so that the wave seems to be dwarfing it and crashing down on Mt Fuji as well as on the poor fishermen in their boats. The droplets of foam coming off the wave start to look like snow falling on Mt Fuji (which famously had snow all the year round). It’s like a reverse perspective, staring down the wrong end of the telescope. Then there’s the pigment. The Prussian blue printing ink that he uses to great effect in the Great Wave is imported, sometimes from Europe or, by the 1830s, more likely from China. It is an exotic, imported pigment.

It is almost as if, with an ambitious encyclopaedic project like this, Hokusai’s restless creative energy and curiosity is wanting to compensate for the fact that Japan’s government has deliberately closed it to the outside world. It’s not a limitation for Hokusai. He is able to fly through time and space and come up with intensely enjoyable picturisations of these famous episodes of ancient Asian history. The one thing he can’t do is travel abroad. He can’t show contemporary China, so the emphasis is very much on the ancient world.

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). Fumei Chōja and the nine-tailed spirit fox. Fumei Chōja appears as a character in kabuki and bunraku plays which also feature the shape-shifting nine-tailed fox and its adventures in India, China and Japan. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

JR: There are also some fabulous animals?

TC: Yes, and they are often looking at you. They set up the communication between what is happening in the drawing and the person looking at it. This is a feature particularly of Hokusai’s late works. In picture No 4, which I found very exciting as soon as I saw it, all the ducks and the swan have Chinese characters naming them, sometimes several. In the top righthand corner, for instance, the little grebes are named with five different characters that can be used to write “little grebe”.

What really popped out at me in this drawing, though, was the bird in the centre of the bottom row – a mallard duck looking sideways. The drawing is 1829, but in the British Museum collection there is a famous painting by Hokusai done in 1847 (when he is 88), Ducks in Flowing Water, in which the same bird appears – but this time looking at us. There is another mallard in the painting that is silhouetted diving, just like the little grebe in this drawing. We see this again and again in Hokusai. He plays with a subject, then he drops it, but, at some later period in his career, he’ll revive it and start playing with it again. And the later we get in his career, the more satisfying, the more exciting are the versions. The animal drawings are spread between London and Boston and they don’t directly have anything to do with India and China. I think it is pretty clear that the drawings have become shuffled and the 103 in London are in random order.

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). Painting, hanging scroll, 1847. Two mallards paddling in a flowing stream: one diving amongst water-weeds; maple leaves on water surface. Ink and colour on silk. Signed and sealed. With paulownia storage box. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

JR: How do you think that happened?

TC: After the publishing project was abandoned, I think the drawings would have been pasted into a blank of the finished book in small horizontal format. The drawings have since been neatly cut out (they are on very thin paper to make the job of the block cutter easier) and another thin sheet pasted behind each one before it is mounted on card. There’s a beautiful wooden presentation box that neatly holds the whole set. I don’t think many, if any, are missing, but they’ve been converted from working drawings into individual works of art for contemplation. I just hope Hokusai saw some benefit from that – that he was the one who sold it as a presentation set.

JR: When and how did the drawings find their way to Europe?

TC: Almost undoubtedly at the end of the 19th or in the early 20th century, because they have the seal of probably the most famous collector of Japanese art at the time, Henri Vever (1854-1942). He was quite secretive about what he had. He amassed a huge collection of Japanese colour prints, which were disposed of in tranches over the whole of the 20th century, even after he died. The last sighting of the British Museum’s 103 drawings was in 1948 when they were sold in Paris in a sale of works from his collection. That is the last record we have of them.

JR: So how did they reappear?

TC: At auction in Paris, last summer.

JR: Who put them up for sale? Where were they in between?

TC: I have asked many times, but saleroom confidentiality is impenetrable. The auctioneers did say that they had been in a private collection in France. That’s all we know. I should say checks were carried out on databases of lost and stolen art. Thankfully, we have the Henri Vever seal and the connections with the Boston Group. And there’s another connection. In the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, there is the Curtis album of about 130 Hokusai drawings, not finished works, but fragments and sketches, and about half a dozen of these are earlier stage versions of the British Museum drawings. Rather more relate to drawings in Boston.

I would drive myself nuts if I tried to figure out all these connections without some digital help – and assistance from colleagues in other museums – so another really exciting thing we are doing with these drawings is using the new tool the British Museum has been developing, ResearchSpace. I’ve been very lucky to work with the ResearchSpace team on reconnecting these threads. We can interrogate databases and images from several collaborating museums at once, and then share what we find. It is a pioneering system and it is being invented as we are using it.

JR: How important do you think these 103 rediscovered drawings are in the broader artistic context?

TC: I’m so close to this group – I’ve been living with them for nearly a year now – but I think I do have a perspective on the wider field of Hokusai studies and the art world, and I think they are important, and that it is the right time to talk about Hokusai as a world artist. With this particular set of drawings, you can see how his vision is on a world scale, as far as he is able with the restrictions he was living under. This set is a really important piece of the jigsaw – more, a cluster of pieces – and I think we owe it to the man to try to reconstruct the jigsaw as fully as possible. We’ve got subject matter here, too, that is not otherwise much treated in Hokusai’s known corpus, particularly the focus on ancient India and China, and the desire to present these in a way ordinary people can, and will want to, engage with. As in other late works on Chinese poetry and Confucian maxims, Hokusai sometimes draws in lively contemporary style or finds contemporary Japanese equivalents. He is reinventing the classics and making them accessible to a popular audience, and this set of drawings is a relatively early example of that phenomenon.

JR: Hokusai does stand out in Japanese art, doesn’t he?

TC: He stands out for the approachability, the sophistication and the interest of his art and, as importantly, for the fact that he wanted to make this art as widely spread in society as possible. Japanese society was highly stratified in his period and there are many artists who had far higher social status but, to my mind, they don’t do pictures or treat subjects that ordinary people are going to find as interesting. They all have their own ideological slants on the world that, frankly, sometimes just get in the way. Whereas Hokusai consistently – even if the subject is ancient China, which you’d think would be dry as dust – finds a way of taking us there. He absorbs the world and processes it in this extraordinary way and then shares it back with us. There’s a phrase that comes in quite a few of his book titles, including as the subtitle of the Manga: “Received from the gods, and shared with open hands.”

JR: Even today, he is far more popular and more widely known than any other Japanese artist, especially for the Great Wave. What is it about that image do you think that makes it quite so universally appealing?

TC: Well, it grabs you! The wave is converted into what Van Gogh described as the claws of an animal. Van Gogh was, in fact, one of the first to write a sophisticated appreciation of the Great Wave in Europe. It was in an exchange with his brother, Theo. Vincent talks about two things he finds so admirable: the non-naturalistic colour and the power of the draughtsmanship, the way the lines all moves in the same direction. Isn’t that amazing, that one of the first people in Europe to really appreciate this print should be Van Gogh?

Japanese prints were coming to Paris, and then spreading out from Paris, in vast quantities – hundreds of thousands. In 1867 and 1878, there were big international exhibitions in Paris featuring Japanese works, including Hokusai, and by the 1870s the Japonisme movement was well underway and spread to the UK, America and other parts of Europe. Hokusai was, in a sense, at the vanguard of that movement. By 1896, you have the first serious biography of Hokusai in Europe (by Edmond de Goncourt). And he has remained one of the most famous non-European/American artists in the world and I think that status has just grown – and grown exponentially in the internet age. Even people who don’t know Hokusai’s name, know the Great Wave, and that image has become a sort of shorthand for the power of nature. You’ve got the power of nature represented by the wave, man dwarfed in the fishing boats, and you’ve got the sacred represented by Mt Fuji (a deity in the native Shinto religion). All that condensed into a single sheet of paper.

JR: Have you found any precursors for the Thirty-Six Views of Mt Fuji in the 103 drawings?

TC: There is tentacle wave imagery scattered around these drawings, like the Bear in the Mountain Stream, and that goes straight into the Great Wave. In the related Boston set, there are some specific water studies and waves, so it was definitely in his mind.

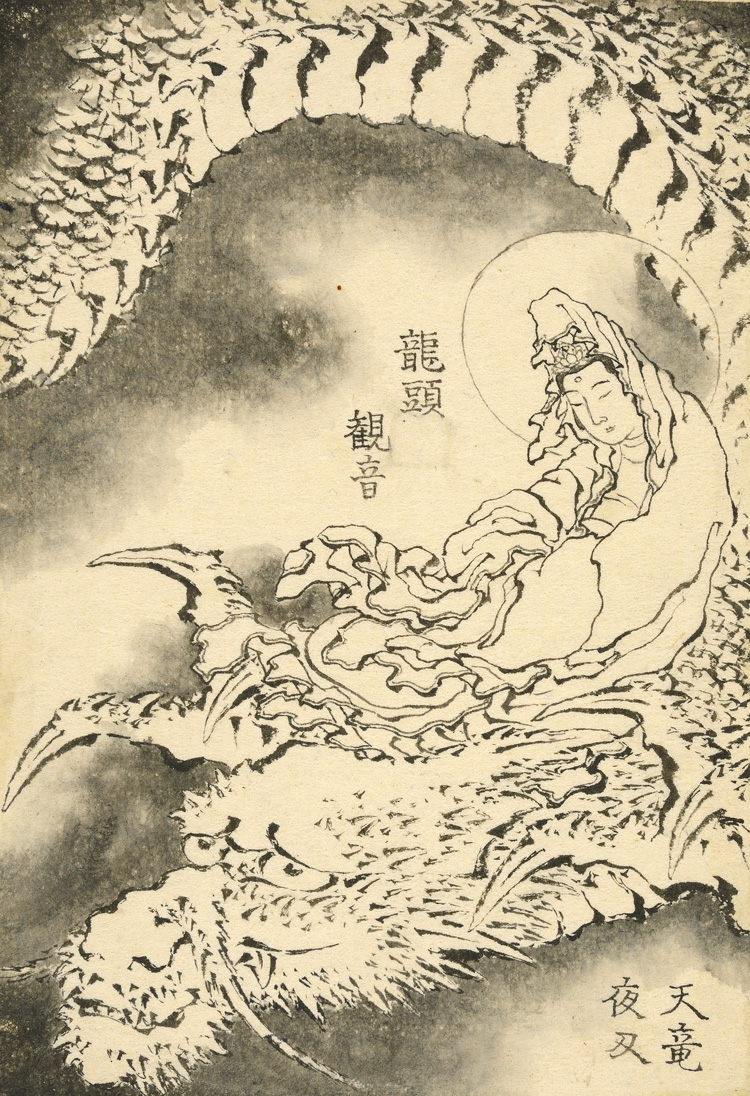

Katsushika Hokusai (葛飾北斎). Dragon head Kannon. In one of thirty-three manifestations of Kannon (Avalokitesvara), the bodhisattva of compassion, the deity appears seated on the head of a dragon. A similar composition by Hokusai is included in the printed album Hokusai shashin gafu published in 1814, although this brush-drawn version is superior. The modulated ink wash of the clouds and the dark scaling on the dragon’s body are particularly skilful. Katsushika Hokusai, 1829. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

JR: Do you have a favourite among the drawings?

TC: No 46. It’s of the Buddhist deity Kannon – the bodhisattva of compassion – riding on the head of a dragon; an incredible coiling ancient dragon amid rain clouds, because dragons generate the rain. For me personally, the dragon is one of the great subjects that Hokusai returns to again and again, and this drawing makes me think of one of his very last paintings that he did aged 90, in 1849, now in the Musée Guimet in Paris. In the drawing, the dragon is not yet looking right out at us, that happens in the painting, but I really enjoy his expression. He’s old and gnarled and has these extraordinary claws, but he’s a very sympathetic dragon. What I delight in most, though, is the contrast between the calmness of the deity and the wind fluttering the robes, and the lines underneath the scales on the coiling body at the top of the drawing. Underneath the spiny top of the dragon’s body, there are what look like articulated plates and the lines between them, I guess representing shadow, drawn quickly and with complete confidence, each have a completely different character.

In these drawings, as in any good Hokusai brush drawing, he never repeats a line, even tiny dots have an individual character. That’s the kind of thing that, as an art historian, I take delight in, as well as the energy that radiates off that sort of brush skill. And this image is the size of a picture postcard.

JR: Hokusai really seems to have been an artist who ripened with age?

TC: The older he gets, the more his personal style becomes highly sophisticated and developed. You look at a drawing and you know it’s a Hokusai figure – the sense of geniality and humour and quirkiness jumps out at you. He combines that with an incredibly deep spiritual side. He was a devout Nichiren Buddhist and he personally derived tremendous support and energy from his Buddhist beliefs, which stress continuity and connectedness in the living world, and even in inanimate objects. Everything has a spirit that is connected to other things. I think that’s a good way of looking at his sense of life. It’s not at all unusual for this period in Japanese culture that people are able to combine profound spirituality with humour and enjoying life. In fact those two things are not seen as in any way opposite and Hokusai absolutely combines them.

• All the drawings will be shown in a free exhibition at the British Museum, 30 September 2021 – 30 January 2022, Room 90. They are already all online here.