Thao Nguyen Phan: Becoming Alluvium, 2019. Installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, 2020. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

Chisenhale Gallery, London

26 September – December 2020 (Reopening 2 December - 13 December.)

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Thao Nguyen Phan’s newly commissioned, 17-minute film Becoming Alluvium is topped, tailed and interlaced with myths and fairytales attached to the Mekong river. It is, says the artist, “my contemplation on the glory and the tragedy of the Mekong River and the countries that are nurtured by it”. In and around the captivating stories of people’s karmic transformation into flowers or fish, and princesses demanding impossible treasures (jewels made from monsoon dew) that cost the lives of innocents, Phan has woven images of the river in all its moods and incarnations: swollen and vast; its forces harnessed in hydroelectric dams or by fleets of industrial barges; disappearing quietly into thick jungle; being traversed by ferry, or crossed via bridges on foot and motorbike. Its plants and animals emerge in closeup; its shifting vistas depict the many uses and abuses it endures on its journey from Tibet, through China, Burma, Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, until it finally reaches Vietnam, where it joins with what Vietnam calls the East Sea and China calls the South China Sea. Through the complexity and variety of these scenes and the hypnotic pace and rhythm of each sequence, the river’s volatile character is revealed – a living thing, vibrant and troubled, its presence conveyed via heat, motion and shimmering, translucent light.

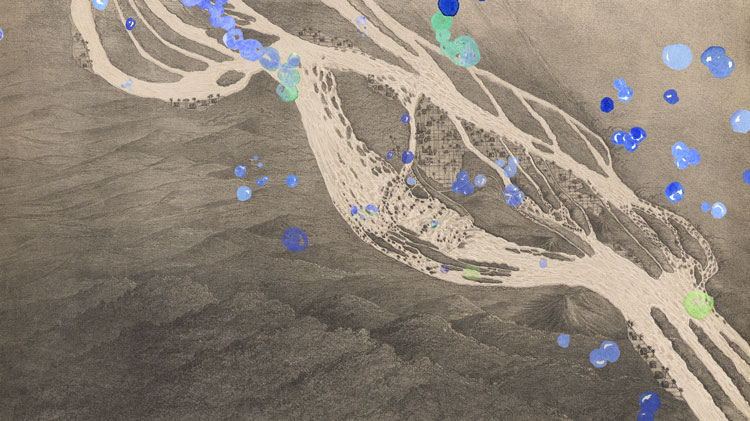

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019. Video still. Single channel video installation, 16:40 mins, loop, colour. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

Its geographic and cultural terrain make it, says Phan, the “river of Buddhism”, but, she says: “Unlike the teachings of compassion and mindfulness that are taught by Buddha, in reality, the land that the Mekong River travels through experiences extreme turbulence and conflict, on a human and a biological scale.”

The corrosive impact of humans on this vast body of water is evoked in more concrete form in a large arrangement of six connecting panels that stands just inside the entrance to the Chisenhale’s gallery space, left of the screen. The Mekong’s meandering route is picked out in delicate, silver and gold lacquer, against a background of dark greys and greens. In a fascinating online talk arranged by the Chisenhale between Phan and Zoe Butt, a Vietnam-based curator, Phan says: “This is a representation of the Mekong, as it flows through Vietnam and before it reaches the ocean. It’s an aerial map.” But the map itself is a fiction, on two counts: partly because, she says, it only resembles the river as it is for half the year, when it is dry. In Monsoon season, water fills up the landscape, transforming much of the land into a wide, alluvial expanse of sand and water. Also, she tells us, this is an official map. It is not even accurate any more because so much damming has gone on over the last decades. This version no longer exists in any season.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Perpetual Brightness, 2019-20. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

This interweaving of fact and fiction is a trademark of Phan’s work, the contradictions and complexities evoked via her chosen mixture of moving image, sculpture and painting. In a text interview with the Chisenhale’s senior curator, Ellen Greig, which accompanies the exhibition, Phan says: “My work is usually research based, often looking at historic archives, but I alter this research to include poetics and fiction. I observe Vietnamese official history as a grand myth, and in many ways, folklore, fiction and oral history can carry more truth than historic account.”

Phan also tells Greig that the presence of her lacquer works is important as part of a post-colonial critique, examining the particular model of art education that still prevails in Vietnam. Established by the French during their colonisation of the region, via the École Supérieure des Beaux Arts de l’Indochine, it combines 20th-century painting and sculpture with traditional Asian arts such as lacquer, a medium Phan majored in during her studies in 2005-8. “In Vietnam, lacquer is considered one of the highest forms of fine art,” she says. But lacquer-work also has resonance in this exhibition’s context thanks to its processes. As Phan tells Butt: “I chose the medium of lacquer … for the relationship to sediment and water. The layers of lacquer can only be revealed by sanding and then rinsing with water.”

Thao Nguyen Phan, Perpetual Brightness, 2019-20. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

On the other side of her lacquered screens are six watercolour paintings on silk, their delicate tones dimmed by the darkness of the gallery lighting, which prioritises the main event – Phan’s film. These watercolours and the lacquer work on the reverse are all part of a work called Perpetual Brightness (2019 and 2020). Along the upper three panels, the paintings depict different but linked scenes:in the upper panels, contemporary young people lark about in rice paddies, then spray chemicals on to the crops; nearby, insects play funeral music by moonlight. The lower three panels depict a young boy comforting an Irrawaddy dolphin – an endangered species that once proliferated in the Mekong - clearly stranded on the shore.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Perpetual Brightness, 2019-20. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

On the wall behind this work is Delta (2020), made in red lacquer with a circular motif in gold leaf, which Phan says references the Chinese lunar calendar – also known as the agricultural calendar. It represents “an ancient timekeeping system that was also popular in Japan, Korea and Vietnam”, Phan tells Greig, and, although these countries have officially switched to the Gregorian calendar, most farmers still use the lunar one, because it offers a better map for agricultural activities.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019. Single channel video installation, 16:40 mins, loop, colour. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

In their online conversation, Butt asked Phan how she chooses between lacquer, paintings and moving image, or what inspires the treatment, for example, of Becoming Alluvium, which uses film for its first two “chapters” and illustrated animation for its third. The choice of when to use what, she says, is intuitive. In researching the third chapter – which tells the aforementioned story of an imperious princess and her quest for jewellery made of dew – she came across archive photography of Vietnamese women who participated in the Vietnam war (an estimated 11,000 women may have played an active role in the Viet Cong). These women were often farmers, she tells Butt, and wore the field workers’ “uniform” of simple cotton shirts and trousers, but they often wore a traditional Vietnamese scarf over their faces to hide their identity. Having seen some of this archive photography, it is clear what has inspired many scenes in this final chapter: the “princess” appears in field workers’ uniform, her head either missing or represented by a floating scarf. The colourings of these illustrations are pearly, sorbet hues of pink, yellow, purple and red, against a black-and-white drawn background.

Thao Nguyen Phan, Becoming Alluvium, 2019. Single channel video installation, 16:40 mins, loop, colour. Produced and commissioned by Han Nefkens Foundation in collaboration with: Joan Miró Foundation, Barcelona; WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels; and Chisenhale Gallery. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Andy Keate.

There is so much to unpack in this offering, it is a shame that coronavirus restrictions limit visitors to 20-minute slots - I would happily have watched the film twice, the better to appreciate the marriage of this compelling imagery and the accompanying words (as we neared publication, Greig was hoping a deal with online independent movie streaming service MUBI might actually make wider viewing of Phan’s films, including this one, possible). Phan was inspired to use others’ texts for chapters one and two. There are quotes from a poem by Rabindranath Tagore, The Gardener (Why did the flower fade?/I pressed it to my heart with anxious love/That is why the flower faded/Why did the stream dry up?/I put a dam across it to have it for my use/That is why the stream dried up). Elsewhere, there are elements of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities and Marguerite Duras’s The Lover, an autobiographical novel about her teenage years in Indo-China and falling in love with an older Chinese-Vietnamese man.

Ultimately, it is no surprise to learn that Phan has been studying, researching and responding to this river in her work for more than a decade. I was struck by this richness of source material; a river with so many myths and narratives attached to it can surely never die.