Sara Shamma in her London studio, 2023. Photo: Juliet Rix.

by JULIET RIX

The figurative-abstract colourist paintings of Sara Shamma present the surface and the interior of her subjects simultaneously. Though formally trained from the age of 14, she works intuitively and very much on her own terms.

Born in Damascus in 1975 to a Syrian father and Lebanese mother, Shamma’s talent was recognised early and nurtured by her parents. She attended an art academy part-time while still at high school, before studying painting at Damascus University. The course did not impress her, but it gave her time to develop her style and technique, and the opportunity for a large graduation show in 1998 that helped make her name in Syria.

Shamma has long been interested in psychology, and in death – which she sees as giving meaning to life – and her themes have included motherhood, children’s perspectives, modern slavery and war. She often uses herself as a model and has done occasional portraits of other named individuals. She combines figurative with abstract approaches and elements of her work might be seen as having something in common with Francis Bacon or Lucian Freud but without the edge of cruelty and despair, and with more beauty and hope.

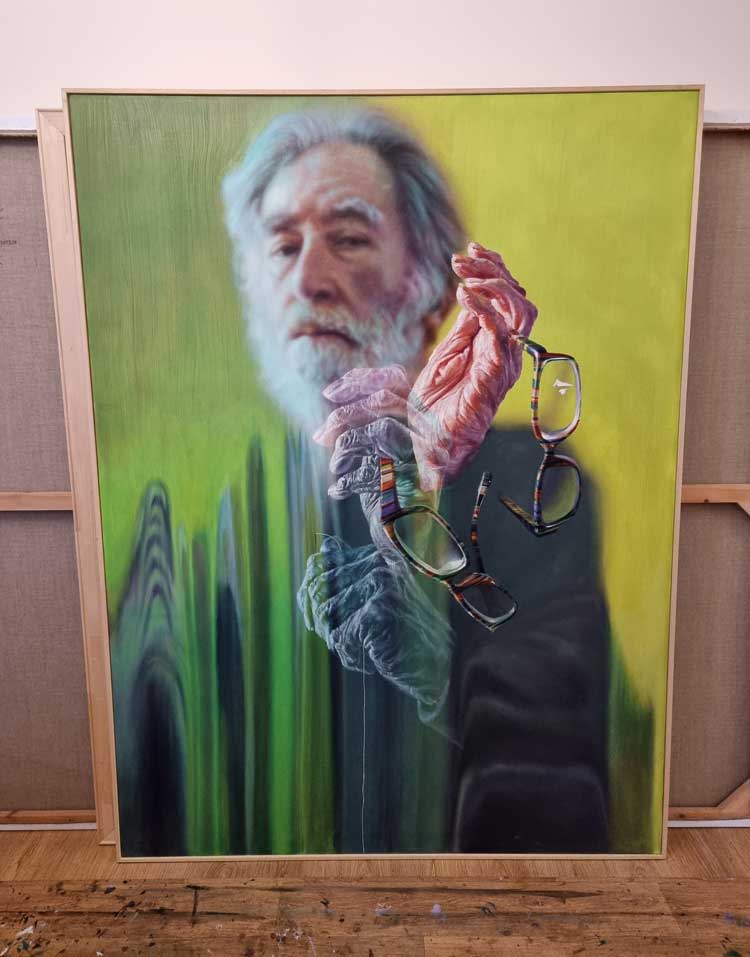

Sara Shamma in her studio with Self Portrait, 2019. Photo: Juliet Rix.

In 2004, Shamma won fourth prize in the London National Portrait Gallery’s BP Portrait Awards and went on to work and exhibit regularly in London. In 2016, after two years based in her mother’s home town in northern Lebanon to escape the war in Syria, Shamma was granted a UK “exceptional talent” visa and moved with her husband and two young children to south-east London. This is where she lives and works today, though she visits Damascus regularly and keeps a studio there.

Just after the NPG Award, Jennifer Scott, now director of the Dulwich Picture Gallery, was giving a public talk about the winning works. She had just been singing the praises of Shamma’s entry, when, as Scott describes it: “I had an almost out of body experience.” Shamma walked through the door. Scott recognised her immediately because Shamma’s winning painting was a realistic self-portrait. Thirteen years later, with Dulwich now Shamma’s local gallery, they met again, and the result was the current exhibition there, Bold Spirits.

Studio International caught up with Shamma at her London home-studio where her often larger-than-life portraits and figures cover the walls.

Juliet Rix: Your work is a beguiling mix of figurative and abstract. What is your painting process?

Sara Shamma: My work is not classically figurative; I use figures but also abstraction and a touch of surrealism. I don’t do preparatory sketches. When I paint, I am in a state a bit like meditation (though I don’t meditate). I do it in an instinctive way. I put my mind aside, I put on music I love and just work and see what the result is. I may start from something – my face, a mirror (I work a lot with reflections), a hand. I am interested in bodies (including dancers’ bodies), but I do not work direct from live models. I take photographs and then work from imagination.

If anyone comes into the studio, that’s OK. I am not one of those artists who can only work in isolation. I can isolate myself in any circumstances – I love this gift that I have. I can talk on the phone too – even have a serious conversation like with a friend who has left her boyfriend – and keep painting. Friends understand that I do this. Sometimes, the person I am speaking to or someone in the studio adds something – unconsciously – to the painting.

Sara Shamma. Portrait of artist Tom Phillips, 2019. Photo: Juliet Rix.

JR: That is a remarkable kind of concentration.

SS: I have always been able to do that. As a child I could stare for an hour at the clouds. I still do. When I travel, disconnected from time and place, I can spend the whole journey looking at clouds and come to ideas and conclusions. I think without words, without language.

When I was very young, I used to go to bed and close my eyes and before sleeping I would feel I was flying or diving and I used to enjoy this and play with it. As we grow up, most children lose this, along with the innate ability to concentrate intently on the tiniest thing. I still have this, and I do not want to lose it. When I reach this state of mind, I can create. That’s how I can make something new – at least to me; how I can surprise myself.

I used to do it without understanding what I was doing. As I got older, I learned to control and channel it. I read about psychology, states of relaxation, Sufism (not in a religious way, I am not religious at all) – about ways of reaching this state of mind. I’ve concluded that you can’t really teach it. You can get some way with practice, but in the end you either have it or you don’t.

Sara Shamma. Woman in Smoke, 2014. Photo: Juliet Rix.

JR: It is interesting that you raise psychology and working almost unconsciously. The abstract elements in your otherwise figurative, relatively realistic, work seem to take the viewer beneath the surface of the image.

SS: I love the contrast of hyperrealism with the abstract parts. And the difference between the layers of paint – transparent and thick. It keeps the eye entertained. Looking at something that is all one thickness, all the same, the eye gets bored. And transparent colour makes your eye go deeper, while the thick colour comes closer to you. It reflects light more, jumping out into your eyes.

JR: And it isn’t just the eye that is drawn in, the abstract elements seem to take you inwards psychologically too?

SS: Yes. Whenever you paint a portrait or figure, anything you do on top of it takes you inside psychologically. Eye contact also creates psychological interest. And when you see only part of a figure, the viewer’s imagination starts to work.

JR: You say you have retained a child-like ability to focus and ignore the physical. You have also put children into your work quite a lot.

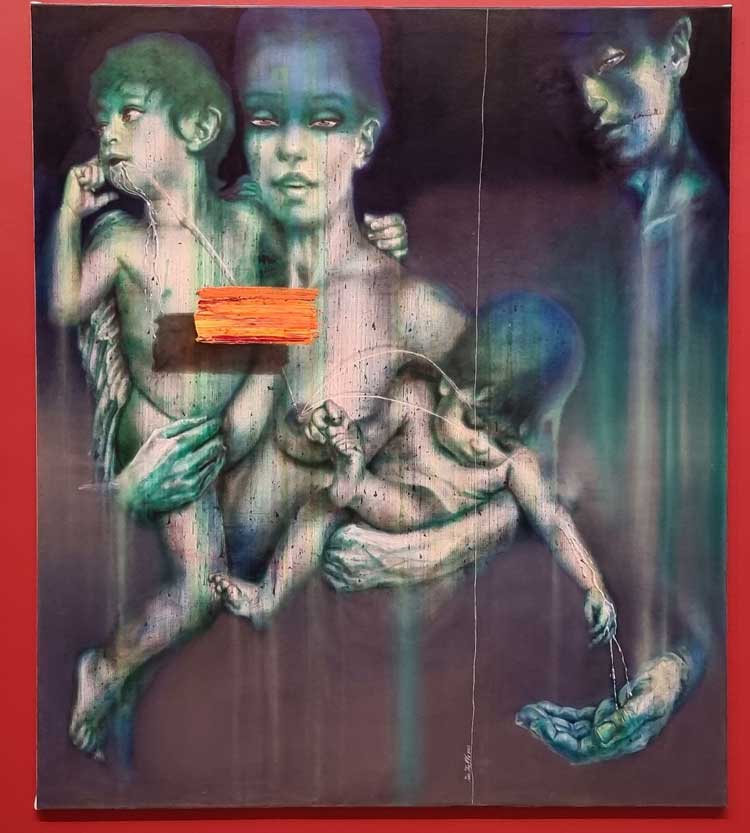

SS: I love children. They are very inspiring. I did an exhibition in 2008 about motherhood and milk before I was even pregnant, before I’d even met my husband. I used friends’ babies and their mothers feeding them. It’s the making of life.

In 2010, I got pregnant, and becoming a mother made me understood a lot about creation. Motherhood makes everything bigger. Love is bigger, anxiety is bigger, anger is bigger (in defence of your children), strength is bigger. Some people say children suck you dry. I feel totally the opposite. It is easy to get old and lazy and lose interest. Children renew you.

Sara Shamma: Bold Spirits, installation view, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 9 September 2023 - 25 February 2024. Photo courtesy Dulwich Picture Gallery.

JR: Within your art, do children represent that ultimate creation, creation of life, or are they there for their ways of seeing the world, their imagination?

SS: All those things. I look into their eyes and see everything – even hatred and criminality, as well as purity and innocence, and such curiosity. They have everything in their eyes in a very bold way.

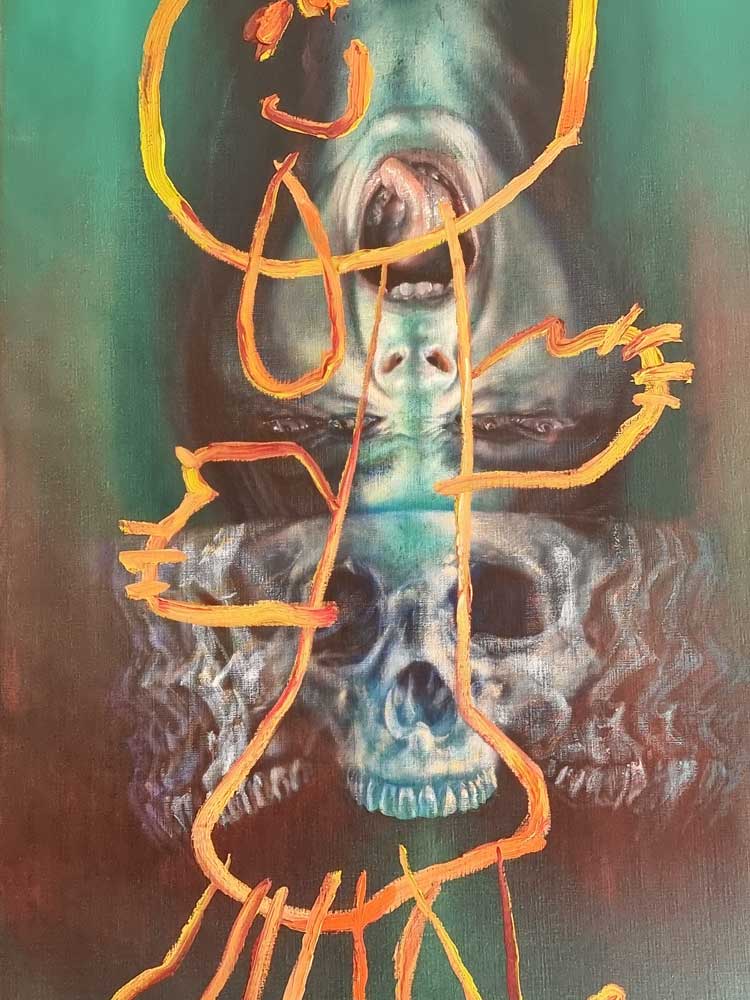

I did a whole project with children’s drawings. It started with a portrait of my son I did in Lebanon in 2014-15. Half his face was not completed, and I suddenly decided to ask him to draw something on the other half. He was about four years old. A couple of years later, I started collecting children’s drawings and copying them on top of my paintings.

.jpg)

Sara Shamma, Untitled, 2023. Oil on canvas, 150 x 115 cm. Copyright and courtesy the artist.

JR: There is a very striking double child portrait in the Dulwich show – your response to Rembrandt’s Girl at a Window (1645).

SS: I love that Rembrandt painting. It is very simple, and it can contain any subject you think about. She could be a maid, a lover, anything. My painting is of my children – from a photo of them on a train some years ago. They are by a window. I love to work with reflection, layers, and transparency, and I’ve worked a lot in the past with figures behind glass. But the children are not looking out of the window. They are focused on a void and talking together. I love this moment. They are totally taken, in that beautiful way children have, by something very small – an idea, a voice …

JR: Is Rembrandt an artist you particularly admire or who particularly influenced you?

SS: I was interested in Rembrandt from when I was very young because we had a poster, a print, of one of his paintings on the wall at home. It is a painting of people in a pub – I can’t remember the name and I’ve never looked it up, but I still have it in my studio in Damascus. We also had a print of Salvador Dalí’s The Last Supper. These two prints were part of my childhood. I remember sitting and gazing into them for hours and hours. That’s what I do – until I start to hallucinate. I loved Rembrandt for the light and the thickness of his brush strokes. And surrealism because of my interest in the unconscious mind.

As I grew up, I stopped loving particular artists. What inspired me most was music and people’s faces and hands and the clouds and the sky and the smell of nature, much more than the history of art.

Sara Shamma. Untitled, 2023. Inspired by Anthony van Dyck's Venetia, Lady Digby, on her Deathbed. Photo: Juliet Rix.

JR: What about contemporary art?

SS: I admire the work of Glenn Brown – his strong technique and figuration and lots of imagination.

I rarely relate to abstract art: some is very interesting, but not a lot. Most I find a little boring. The same is true for installations and performance art. And video art – most is not video and not art. There’s a lot of rubbish in the art world. And a lot of artists who lack confidence. You have to have confidence to create art; you have to believe you are something that has never happened before!

I go to exhibitions – contemporary and historic. That is my homework; it is not for love. But music is for love, and it is now my main inspiration.

JR: What kind of music?

SS: Sufi music from Pakistan, and blues. I sometimes feel there is a connection between them. They are both improvised and can put you in a trance, make you high – the state of mind in which I can create.

JR: Was there music or art in your family?

SS: My father was a civil engineer in love with music – especially hard rock and blues – and he played the drums. My mother studied child psychology and was a social activist with an interest in literature. They noticed that I loved to paint, and they facilitated it for me. I knew when I was 14 that this would be my career. I went to an institute for fine art meant for students aged 18 and over, three times a week after school, for two-and-a-half years before studying painting at Damascus University. For my graduation project, I did big paintings and a big exhibition. I got permission to use the faculty basement. My friends and I cleared it and painted it, and I hung about 35 paintings there.

Sara Shamma: Bold Spirits, installation view, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 9 September 2023 - 25 February 2024. Photo courtesy Dulwich Picture Gallery.

JR: Did that lead to interest beyond the university?

SS: It gained interest from the art world, and my mother also opened a small art gallery when I was in my third year (of four), so I was very lucky. In my early 20s, I gained a big name in Damascus. Without the family support, I think it would have taken me about four years longer to succeed.

And I learned at a young age about the art business. I’m still like a child in this but compared to my artist friends, I know a bit more.

JR: What happened when the war came in Syria?

SS: Nothing major happened in Damascus, but we could hear the bombing and every now and then there would come a missile. In 2014, we moved to my mother’s home town in northern Lebanon, then in 2016 to London.

We started to feel the war in about 2012. Our situation was much better than most. I can’t say it was difficult for me: I have not lost anyone, nor any body part, and our home was not destroyed on top of my head. But the whole world was fighting in Syria. Of course, it affected me.

Sara Shamma. Untitled, 2018. Photo: Juliet Rix.

JR: Did it also affect your work?

SS: Of course. In 2015, I did an exhibition in London, World Civil War Portraits. I made the work because I had a need to express these things. When I look back at the catalogue now, these pictures are very graphic. They show parts of the body – I went to the butcher’s; I watched halal slaughter. I don’t have any taboo with blood – blood is life – or with death. As a student I used to go to the morgue to study anatomy, pretending to be a medical student. Looking back at these paintings, they are very strong, but I needed to do this work.

JR: How did the move to London come about?

SS: Since coming fourth in the National Portrait Gallery BP Portrait Awards, I’d been visiting London once or twice a year to work, exhibit and see art. Friends encouraged me to apply for an “exceptional talent” visa, and the then president of the Royal Academy, Christopher Le Brun, the then director of the Art Fund, Stephen Deuchar, and a curator at the NPG endorsed my application.

I still go back to Damascus with the family every two to three months. We have two different lives. It is tiring but inspiring. I switch between the very different places quite instinctively. I started a painting in Damascus in August, and when I went again in December, I immediately switched back to work on this painting even though I’d been working in London on a completely different project. It’s like driving. In London, I drive on the left side of the road and follow the rules. In Damascus, driving has very different morals. If I drove there as I do here, I’d cause an accident. I automatically switch. I do the same artistically.

Sara Shamma: Bold Spirits, installation view, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, 9 September 2023 - 25 February 2024. Photo courtesy Dulwich Picture Gallery.

JR: Tell me about the Dulwich show. Having not been so interested in old masters for some years, how has it been working on paintings inspired by the old masters you have chosen from the Dulwich collection?

SS: I’ve loved it. I love the gallery and since we moved to London, it is my local. I had not looked much at old masters for a long time, but as a student I studied them – from books, in the library, not in real life. I didn’t travel much at that age. In my first year at university, I used to copy a lot of old masters to learn their techniques. I was not convinced by what I was being taught on my course, so I taught myself by copying. And I used to sell them.

I copied many, many works by many different artists – even Renoir, whose work I hated. I still do. He’s not my cup of tea. But I wanted to try his technique. I copied a Georges de La Tour, Le Tricheur (The Cheat), from a book, but using his techniques – the transparent colours with thicker paint on top. And when, aged 19 or 20, I finally went to the Louvre and saw the original, I was impressed by my ability!

Sara Shamma. Untitled, 2023. Inspired by Peter Paul Rubens' Venus, Mars and Cupid, c1630-35. Photo: Juliet Rix.

JR: The Dulwich paintings you chose to respond to are all of – or include at their hearts – women and children: Rembrandt’s Girl at the Window, as well as Peter Paul Rubens’ Venus, Mars and Cupid (where you have picked up your breast milk theme), Anthony Van Dyck’s Venetia, Lady Digby, on Her Deathbed (which led to a striking image of death), and Francesco Guarino’s Saint Agatha. And you have made a huge painting inspired by Peter Lely’s Nymphs by a Fountain. Which did you most enjoy doing?

SS: The big one (after Lely). I enjoy working on a large scale. And for this one, unusually, I did some preparation. I found the Lely nymphs very inspiring, so I wanted to keep them as they were but distort them. Then I decided to flip it and reflect it left to right. Then I added figures.

To see my paintings next to all these great artists was very impressive for me.

JR: What next?

SS: I have an exhibition in Damascus next year, and one in Beirut (if the situation allows). I am working on a series inspired by dancers for Beirut, about movement of the body. I used to paint the whirling dervishes. For this new project, I went to the Ballet Rambert and took many photos at their rehearsals. So far, I have five or six paintings that I am happy with.

• Sara Shamma: Bold Spirits is at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, until 25 February 2024