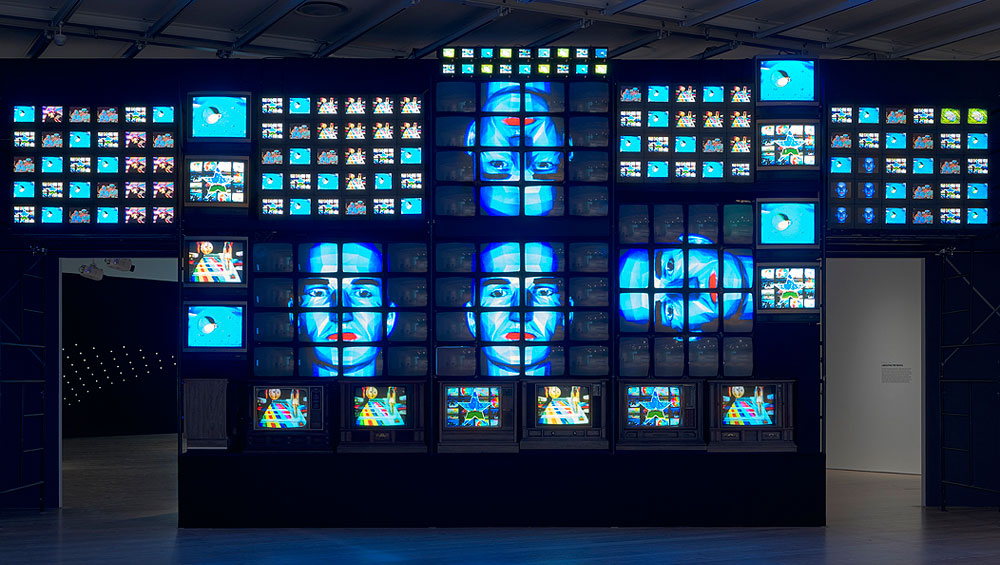

Nam June Paik. Fin de Siècle II, 1989 (partially restored, 2018). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Laila and Thurston Twigg-Smith. © Nam June Paik Estate. Photograph: Ron Amstutz.

The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

28 September 2018 – 14 April 2019

by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

One would expect Programmed: Rules, Codes and Choreographies in Art: 1965-2018 to be a cerebral exhibition tending toward minimalist visuality, but it begins with a bang of sensorial overload. As we enter the museum’s sixth floor, we are confronted by Nam June Paik’s monumental installation Fin de Siècle II, originally made for the Whitney Museum exhibition Image World in 1989. For this work, Paik (1932-2006) arranged more than 200 television sets on top of each other, stacking them up to the ceiling and stretching the work across the floor. The installation overwhelms the senses with flashing screens, dancing and singing figures moving sinuously across them and blaring sounds of 80s pop. The images are on a loop and follow a certain sequence, which becomes apparent only after several minutes of standing in front of the artwork. The momentary impression is that of overflow – auditory and visual – and the necessity of our psychophysiological system to adjust to handling it adequately. Fin de Siècle II is a relatively late work by Paik. It is being shown for the first time in New York since that first outing at the Whitney nearly 30 years ago.

Installation view of Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965-2018 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2018-April 14, 2019). Foreground: Sol LeWitt, Five Towers, 1986. Photograph: Ron Amstutz.

The museum’s conservation department has restored the work and brought old TV monitors back to life following guidelines left by the artist. It is interesting to compare the evolution of Paik’s work, because one of his early experiments with TV, conducted at the dawn of the digital era, is also on display. Called Magnet TV (1965), it is a TV set with a large magnet on top that alters electronic signals coming into the cathode-ray tube, thereby altering the image on the screen. Paik’s early experiments with altering the image on the screen contributed to his fame. They were featured in the historic exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity: the computer and the arts, which took place at the Institute of Contemporary Art in London in 1968.1

Sol LeWitt. Wall Drawing #289, 1976. Wax crayon, graphite pencil, and paint on four walls, dimensions variable. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Gilman Foundation, Inc. 78.1.1-4. © 2018 Sol LeWitt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The stated premise of Programmed is to show “more than 50 years of conceptual, video and computational art drawn largely from the museum’s collection”. We are told that its aim is to bring conceptual and digital art together by “allowing us to examine closely what it means to use rules and code in art’s creation”. The exhibition certainly achieves this, but it also highlights and juxtaposes the opposites in technologically oriented art: the formally rigorous and formally loose domains of “programmed” visuality. On the one hand, we have the sparse, minimal, intellectualistic kind, oriented towards conceptual art practices; on the other, the animated, over-the-top, gaudy imagery characteristic of pop art. Accordingly, the display is divided into two sections: Rules, Instruction, Algorithm, based on conceptual art practices, both human- and program-generated; and Signal, Sequence, Resolution, which foregrounds artists’ experiments with electronic technology that entered the realm of pop culture.

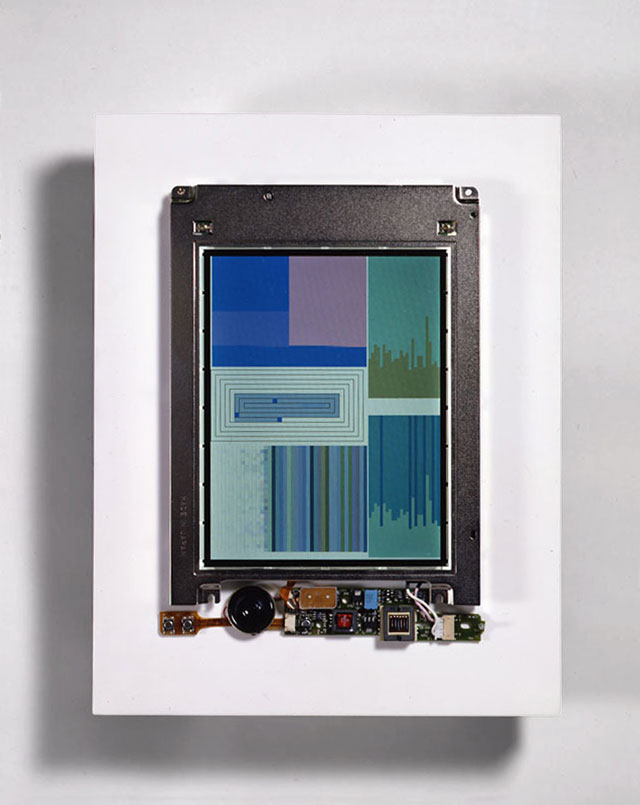

John F. Simon Jr. Color Panel v1.0, 1999. Software, altered Apple Macintosh Powerbook 280c, and acrylic (plastic), 13 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 3 in. (34.3 x 26.7 x 7.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee 99.88a-c. © 1999 John F. Simon Jr.

In the conceptual Rules, Instruction, Algorithm section, we encounter work by Josef Albers (1888-1976), Donald Judd (1928-1994), Sol LeWitt (1928-2007) and Joan Truckenbrod (b1945), as well as younger artists working in a conceptual vein, such as Tauba Auerbach (b1981), Casey Reas (b1972), Mika Tajima (b1975), Rafaël Rozendaal (b1980) and John F Simon Jr (b1963). All of them are grouped under the heading of working with “ideas as form” or rather, metaphorically condensing ideas into form, “employing mathematical principles, creating thought diagrams, or establishing rules for variations of colour”.

Casey Reas. {Software} Structures #003 B, August 2004/2016. Java, Adobe Flash Player. Commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art for its artport website AP.2004.5.

In the older generation, we move from Albers’ painterly elaborations of subtle gradations of colour in his Homages to the Square to Judd’s recently restored sculpture Untitled (1965) and LeWitt’s muralled Wall Drawing #289 (1976). This work by LeWitt is a good illustration of his approach to serial art production. Here, he gives a verbal instruction – 24 lines from the centre, 12 lines from the midpoint of each of the sides, 12 lines from each corner – that functions as a program and can be adapted to any architectural context, because neither the length of lines nor their angles are specified. Apart from works of visual art, it is gratifying to see dance and music integrated into the display of conceptual art. The choreographer and dancer Lucinda Childs (b1940), who collaborated with LeWitt and composer Philip Glass (b1937), is represented by two of her elegant performances: Dance #1-5 and Dance (both from 1979).

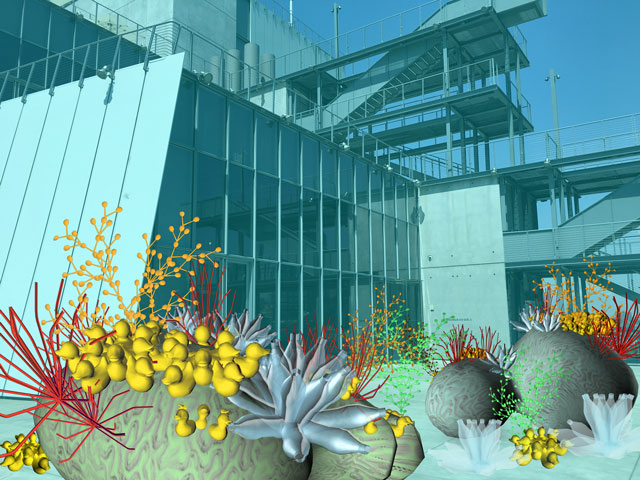

Tamiko Thiel (with /p). Unexpected Growth, 2018. Augmented reality installation, healthy phase. Commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art.

For the younger generation of artists following the Rules, Instruction, Algorithm method, incorporation of ideas into form involves mediation of computerised technology. In her work Binary Uppercase/Lowercase (2005), for example, Auerbach makes visible the abstract nature of computer language – here, she translates one letter of the English alphabet into a binary code, where black squares stand for 1 and white ones for 0. We cannot read the represented letter, but we can trace a complicated play of black-and-white repetitive patterns and notice the differences in representation between the upper- and lower-case codes. Reas is someone who emphasises his connection with the preceding generation, specifically with the work of LeWitt. For his work {Software} Structures #003 A and B (2004 and 2016), executed with JavaScript, Reas begins the process of creating the computerised drawing by describing it in words, like LeWitt. For Reas, it is important to begin the process with an idea formulated in natural language before translating it into a computer code, because he wants to preserve the connection with the audience and also remain present in a more “loose and ambiguous” space created by natural language before moving to its computerised counterpart. Unlike Reas, Ian Cheng (b1984) relegates the control of codification to the computer. In Baby Feat. Ikaria (2013), Cheng employs software that enables an audible conversation between online chatbots. The chatbots are made to “talk” to each other and, because the visuals are linked to the voices, the abstract floating elements on screen, resembling junk or debris, are randomly moving in rhythm with the voices, as if responding to them. Human and computerised intelligence are coalescing in this piece, creating an image of an uncanny abstracted being.

Installation view of Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965-2018 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2018-April 14, 2019). From left to right, top to bottom: Josef Albers, Homage to the Square V, 1967; Josef Albers, Homage to the Square IX, 1967; Josef Albers, Homage to the Square XII, 1967; Josef Albers, Homage to the Square X, 1967; Josef Albers, Variant V, 1966; Josef Albers, Variant VI, 1966; Josef Albers, Variant X, 1966; Josef Albers, Variant IV, 1966; Josef Albers, Variant II, 1966; Josef Albers, Variant VII, 1966; John F. Simon Jr., Color Panel v1.0, 1999. Photograph by Ron Amstutz.

In the section Signal, Sequence, Resolution, linked to the desire-driven pop-art realm, we have an electric signal as a physical form that both reflects and propels the drive and that is sequenced and directed a certain way. Artists working with the pop-imagery of either televised or computerised signals are trying to break down its sequence and redirect its impact. In her work Lorna (1979-1984), Lynn Hershman Leeson (b1941) created an interactive installation in which the viewer is invited to take control of a televised character’s life story. By means of a remote control, we can choose the sequence in which the character, Lorna, who is afraid to leave her apartment, makes her decisions. Depending on the choices we make, there are three possible endings to Lorna’s story – death, escape, or destruction of the TV. A pioneer of narrativised TV installation, Hershman Leeson laid the basis for artistic intervention into mass-produced popular imagery.

Lawrence Weiner. HERE THERE & EVERYWHERE, 1989 (installation view, Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965-2018, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2018-April 14, 2019). Language + the materials referred to, dimensions variable. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Committee 94.136. © Lawrence Weiner/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph: Ron Amstutz.

In a more recent work dealing with the transmission and control of pop-culture images, Cory Arcangel (b1978) alters the code and erases all the elements except one – the clouds – from a cartridge of Super Mario Brothers, the original version of the blockbuster Nintendo video game. The result is Super Mario Clouds (2002), in which we see only the clouds floating against a bright blue background of a sky. For Arcangel, making this kind of work is a game in itself, since it poses the challenge to the viewer to recognise the original source of the image with all of its other elements erased.

Among other works that deal with knowledge of popular culture is America’s Got No Talent (2012 and 2018), by Jonah Brucker-Cohen (b1975) and Katherine Moriwaki (b1975). Here, the artists are commenting on the system of celebrity-making in the US by creating a piece of software that keeps in memory Twitter feeds related to reality-television shows such as American Idol, America’s Got Talent and America’s Best Dance Crew over the course of a few years and then reprocesses them when the work is displayed. The work’s interface is in the shape of the US flag, where the stripes each represent one of popular American reality shows. Thought bubbles spring up every few minutes, transmitting the tweets with the words “no talent” or “America” in them. The work allows us to see that the success of television shows is linked to their social media exposure. Because the tweets are dated, it is possible to trace the popularity of the shows over a period of time.

Installation view of Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965-2018 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2018-April 14, 2019). From left to right: Casey Reas, {Software} Structure #003 A, 2004 and 2016; Casey Reas, {Software} Structure #003 B, 2004 and 2016; Sol LeWitt, 4th Wall: 24 lines from the center, 12 lines from the midpoint of each of the sides, 12 lines from each corner, 1976. Photograph: Ron Amstutz.

In a more serious vein, a politically charged message is conveyed by Mendi + Keith Obadike (both born in 1973), a husband-and-wife performing arts team. In their work The Interaction of Coloreds (2002), they criticise the notion of absence of race discrimination on the internet by making clear that companies and individuals targeting certain groups of customers pay a lot of attention to skin colour. The Obadikes sardonically offered to help these companies by assigning a hex code to people based on their skin colour, determined by looking at photographs featuring different parts of their bodies.

Installation view of Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965-2018 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2018-April 14, 2019). Photograph: Ron Amstutz.

In a less politically charged way, but with the same orientation towards the viewer’s perceptual capabilities and their immediate, gut response is Jim Campbell’s work with LED lights. In his Ambiguous Icon #5 (Running, Falling) from 2000, blinking red LED lights are arranged in a grid to create, and also partially obscure, an image of a running figure. According to Campbell (b1956), in this work, he was trying to imitate a computer screen in low resolution and project a poetic, emotional content to test “what can be portrayed in low resolution and still have meaning”. The title reflects the direction of his investigation. As Campbell says in a recorded explanation of his work: “Ambiguous Icon “is clearly an oxymoron, as icons on a computer screen have no meaning themselves. They’re pointers to other things that have meaning.” Through a series of works, the artist figured out that the screen works as a distraction from the image: “When you’re looking at the digital structure … your brain is actually focusing on these blinking red lights,” thwarting your attempts to see the image that is shielded by them.

Installation view of Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965-2018 (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, September 28, 2018-April 14, 2019). From left to right, top to bottom: Charles Csuri, Sine Curve Man, 1967; Joan Truckenbrod, Curvilinear Perspective, 1979; Joan Truckenbrod, Coded Algorithmic Drawing (#9), 1975; Joan Truckenbrod, Coded Algorithmic Drawing (#45), 1975. Photograph: Ron Amstutz.

Because the exhibition is drawn chiefly from the Whitney collection, it demonstrates the museum’s interest in acquiring state-of-the-art works over an extended period, made by artists whose interests embrace a wide variety of technologies and approaches to the uses of codification. This exhibition provides a chance to examine the history of Whitney’s collecting strategies and witness the diverse ways artists adapt technology to their creative purposes.

Reference

On coverage of Nam June Paik’s contribution to Cybernetic Serendipity, see Norman Bauman, “Five-Year Guaranty,” in Studio International’s special issue Cybernetic Serendipity: The Computer and the Arts, ed. Jasia Reinhardt, pp. 42-43.