Georg Baselitz: A Life in Print, installation view, Kode. Photo: Thor Brødreskift. © Georg Baselitz.

Kode, Bergen, Norway

4 October 2025 – 22 February 2026

by JOE LLOYD

Georg Baselitz is not shy about his position in the pantheon. The day before the present exhibition at Kode opened, he told theTimes: “There isn’t a better artist than myself.” By the evidence of this capacious survey of his work in print, he may be right. In the catalogue, the curator, Cornelius Tittel – who is also editor-in-chief at Blau International and creative director at Die Welt – recounts an unsolicited phone call with Baselitz after his 2021 Centre Pompidou retrospective. They both regretted that the exhibition was not even bigger. “And it’s also a shame”, said the artist, “that museums are no longer interested in prints.”

A Life in Print aims to be a corrective. It is the most comprehensive survey of Baselitz’s printmaking to date, with 244 prints executed between 1964 and 2024. This labyrinthine exhibition features wall after wall hung with prints of sundry sizes, all presented in identical wooden frames. The same motifs emerge again and again: majestic deer and fearsome eagles, dark German forests and lacerating portraits. All will be familiar to those who know Baselitz’s painting. But the variety is such that Baselitz frequently manages to surprise.

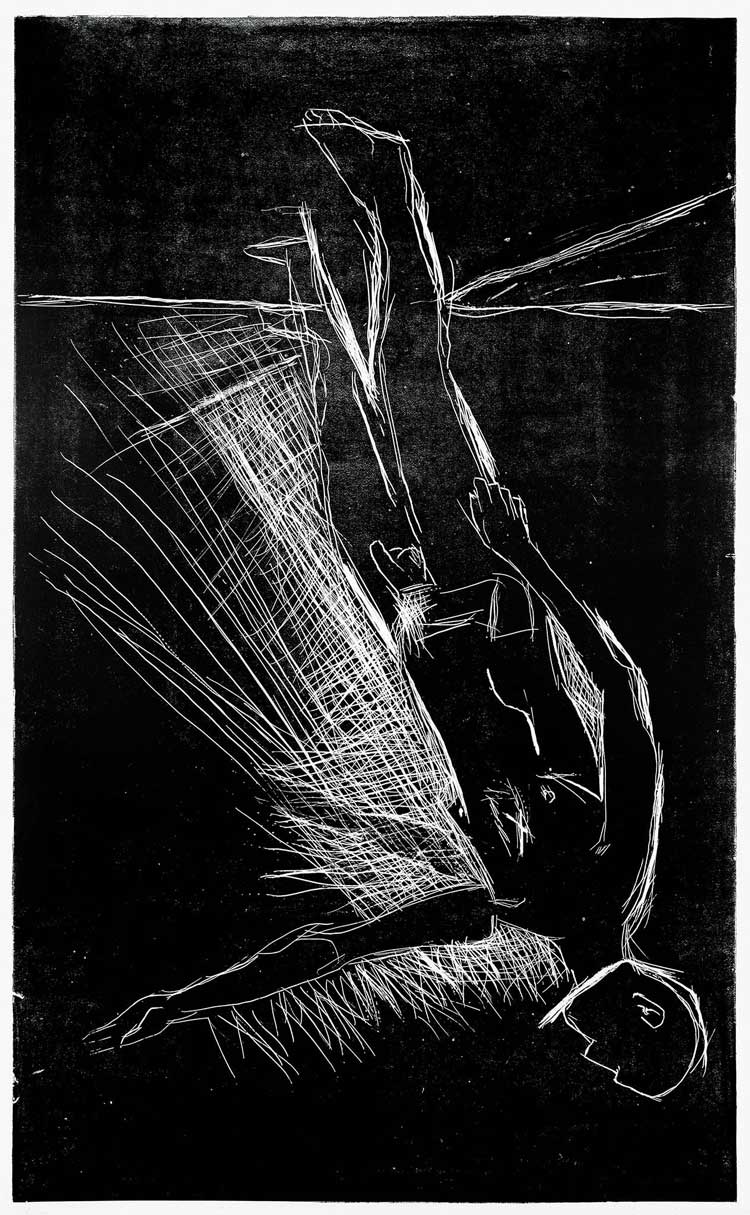

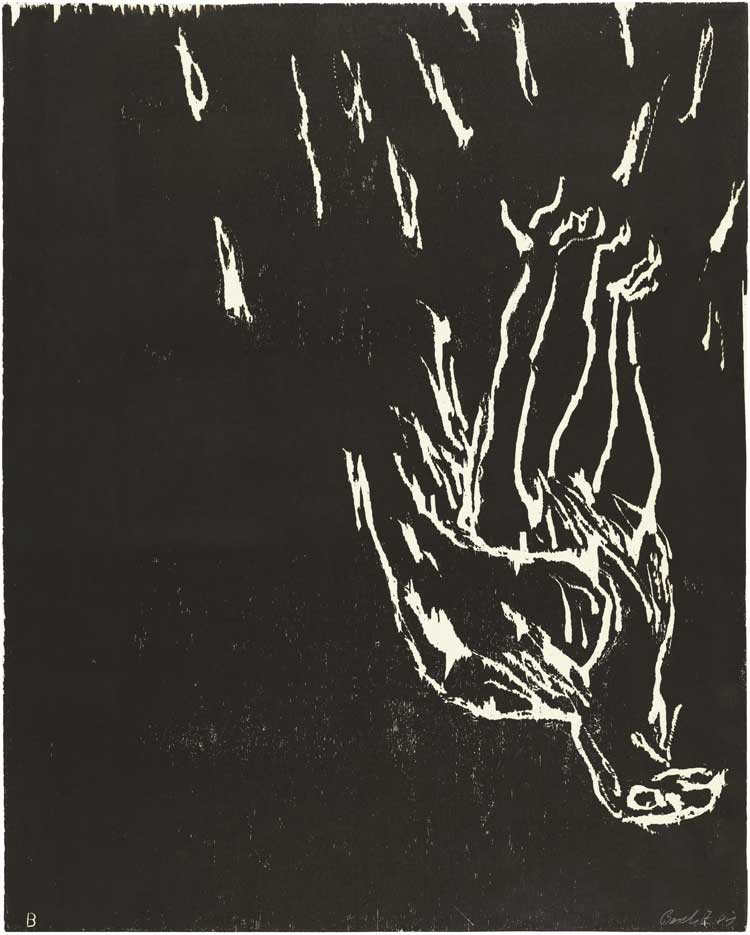

Georg Baselitz, Akt mit drei Armen (Nude with Three Arms), 1977. Linocut. © Georg Baselitz. Photo: Museum Würth / Ivan Baschang.

Born a year before the outbreak of the second world war, Baselitz responded to his childhood experience of destruction by creating works that harked back to German art before National Socialism. His early works featured grotesque figures formed from spatters and sputters of paint, gesturing both to the grotesquery of prewar German expressionism and the painterly melange of American abstract painting. He was viewed as an enfant terrible from the off, expelled from art school in East Berlin for “sociopolitical immaturity”, then accused of “obscenity” after his first solo exhibition in the west in 1963.

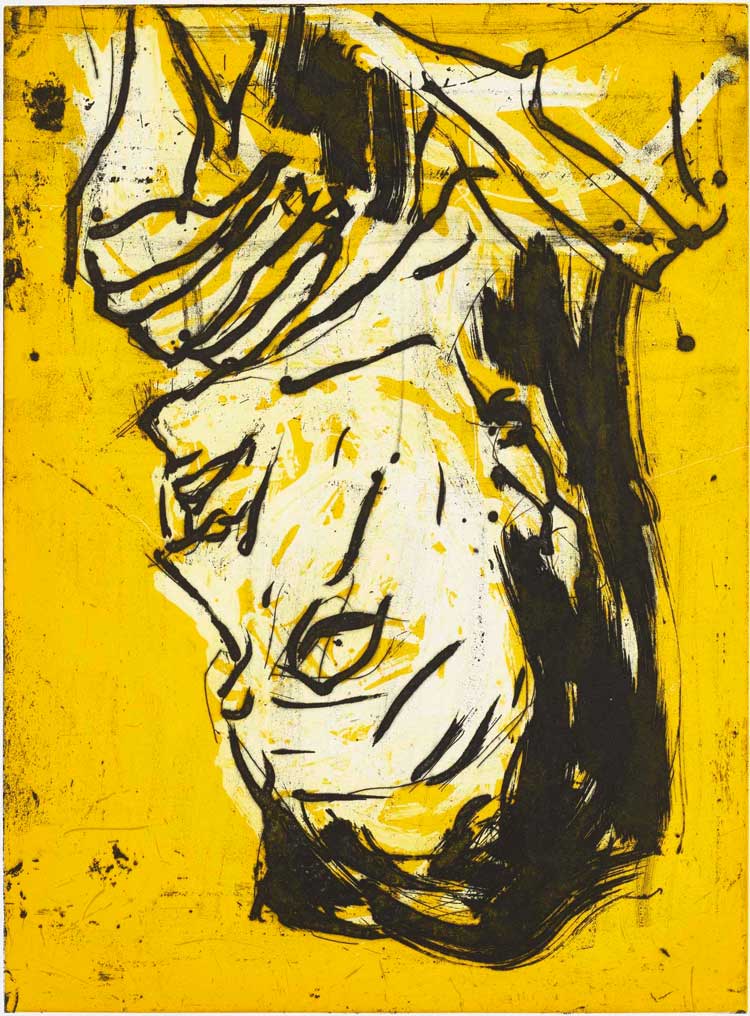

Georg Baselitz, Elke IV, 2017. Linocut. © Georg Baselitz / Photo: P. Cummings / Courtesy Alan Cristea Gallery.

The next spring he was invited to the etching workshop at Schloss Wolfsburg, where his earnest engagement with printmaking began. The following year he spent six months at Villa Romana in Florence, where he became besotted with mannerism – the tail end of the Italian Renaissance, often dismissed for its artifice and distorted figures – and, in particular, the etchings of Parmigianino. While contemporaries such as Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke experimented with screen printing, Baselitz adopted the print techniques of the old masters: drypoint etchings, aquatint, woodcuts and linocuts. In the decades since, Baselitz has used these mediums to revisit the subject matter of his painted work, including his infamous upside-down works.

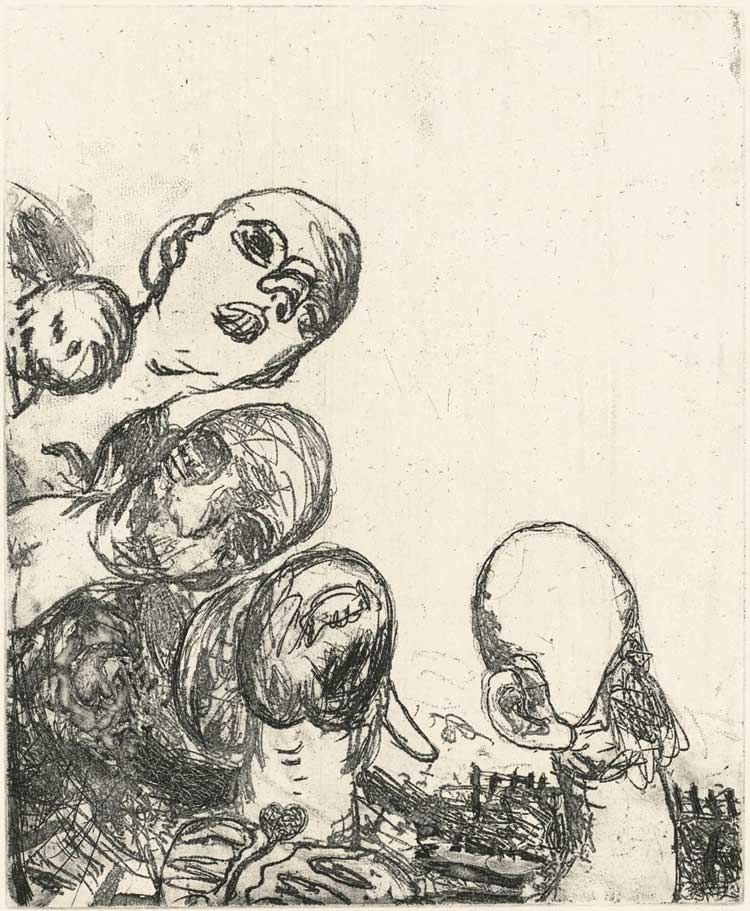

Georg Baselitz, Oberon, 1964. Etching. © Georg Baselitz. Photo: Jochen Littkemann.

The earliest works at Kode are a set of 1964 soft ground etchings of OberonandIdol (both 1963-64), paintings of salmon-hued, near-alien figures with elongated necks, peering out at the beholder with a grimace. One etching catches these ghoulish beings from a different angle, so that, rather than leering at us from above, they crowd around the bottom-left corner, clustered together, jostling for space. Only one of the faces is fully defined – the next two are crisscrossed with obscuring lines, while the final is a blank space with an oversized ear attached. They are both more sinister and more pathetic than their painted forebears.

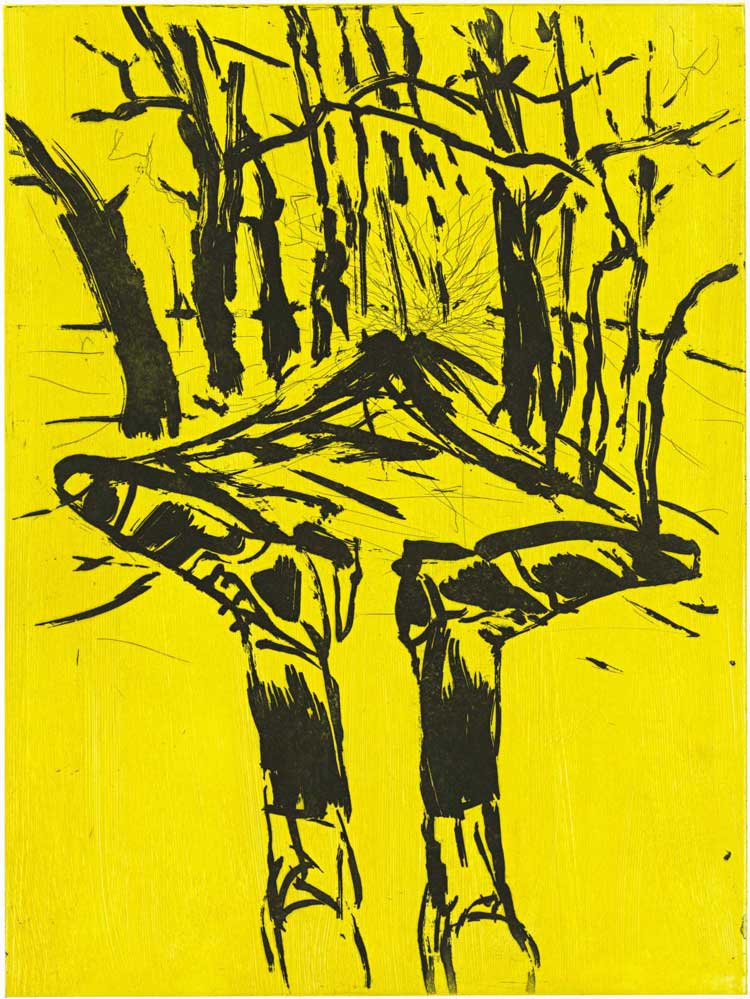

Georg Baselitz, Waldweg, 2004. © Georg Baselitz. Photo: Jochen Littkemann.

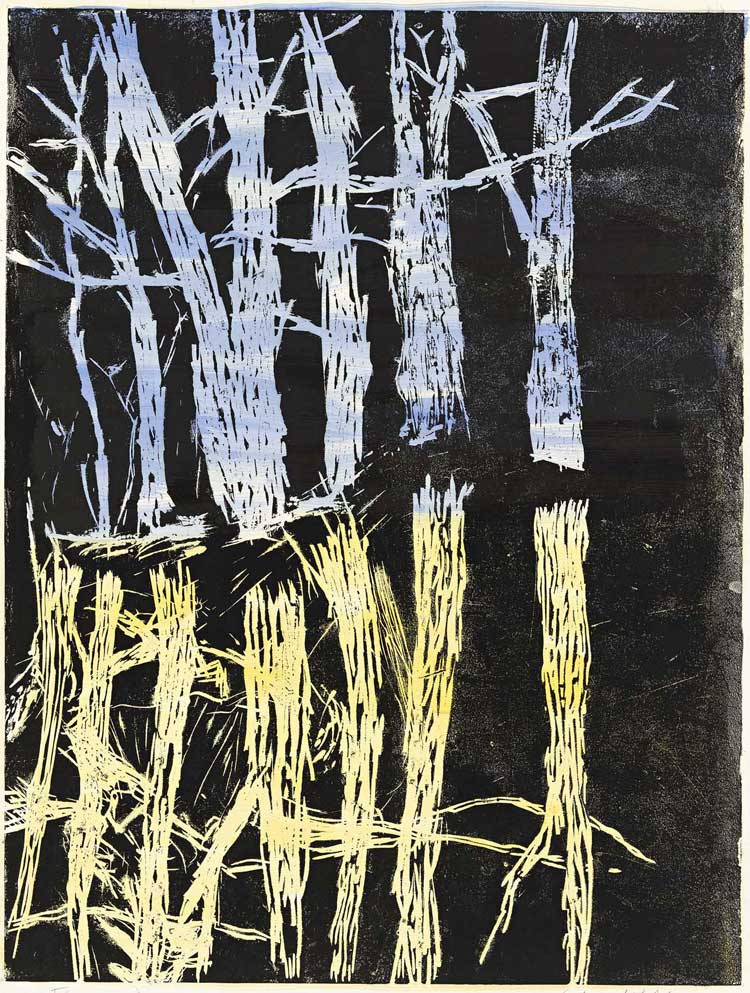

Baselitz’s 1960s etchings hew the closest to precedent. The Shepherd (Der Hirte) (1965) – adapted from one of his Hero paintings (1965-66), which portray bent, broken, worn down archetypes in blasted landscapes – has the contortions and staginess of a Jacopo Pontormo painting. In these earlier, largely black-on-paper works, Baselitz shows a rare proficiency for translating the effects of his heavily impasto, large-scale paintings into a flatter medium. An Untitled 1965 etching shows a figure resembling the shepherd holding a plough, his other hand seemingly bound to a shed-like building. The scene has a full illusion of depth. It also achieves a sense of tactility, a trait that continues throughout his print oeuvre. Green VIII, a woodcut from a 1990 series, even has a texture like tree bark.

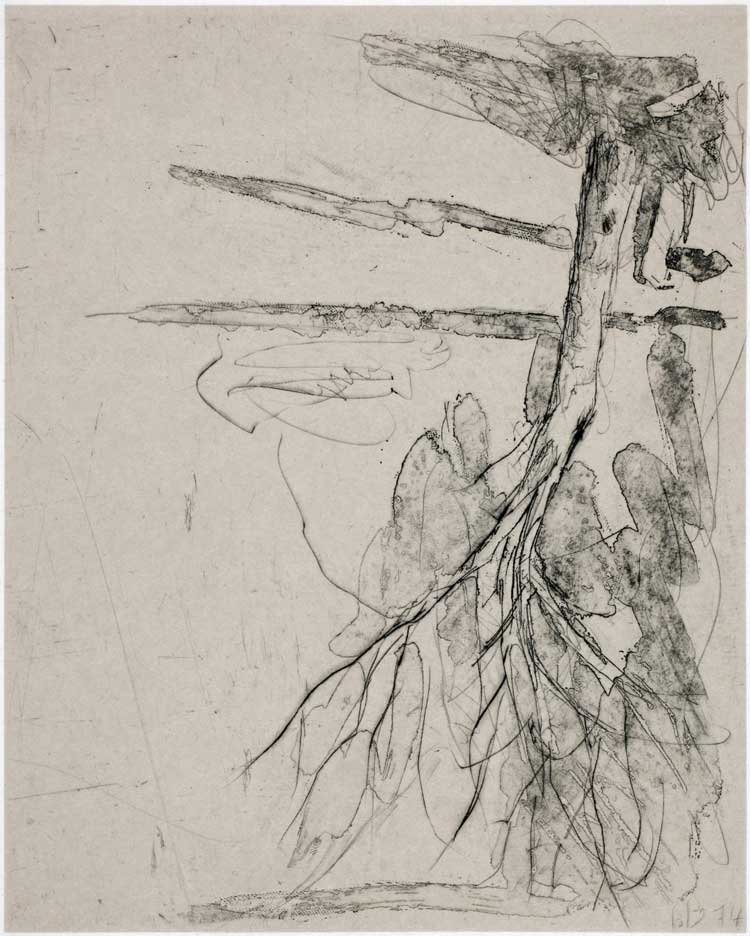

Georg Baselitz, Untitled, 1974. Etching, drypoint and aquatint. © Georg Baselitz. Photo: Siegfried Wameser.

Like the old master prints that inspired them, the early works mostly depicted characters in landscapes, with a conventional perspective. This began to change in the early 1970s. Works from the portfolio Trees (1974) start to isolate their subject matter from a wider whole. A series of eagles from the same year depicts the bird flying in an ambitious plane. At the same time, Baselitz began experimenting with colour, sometimes layering up several on a single print. Two 1992 etchings feature faces on black backgrounds dappled with red, blue and blue splotches, a process that required four plates. As with Edvard Munch before him, many of Baselitz’s prints feature white images surrounded by fields of printed matter. This gives them a strangely primal quality, as if scratched into a tree by a neanderthal. An enormous 1982 linocut features an upside-down head formed from scraggly lines; using lines alone, Baselitz makes each wrinkle visible.

Georg Baselitz, Adler (Eagle) 2 XI, 1981. © Georg Baselitz. Photo: Farbanalyse.

Through the exhibition there is an interesting push and pull between what Baselitz chooses to reveal and conceal. Faces are simultaneously well defined and covered in a field of black spots. A 1979 woodcut called Small Eagle sees the bird surrounded by a maelstrom of ambiguous marks, including what might be the outlines of booted feet and numerical characters. The mode in which he chooses to represent his recurrent motifs constantly shifts. One large 1985 linocut depicts a deer with almost Chagall-esque whimsy, a fluffy mascot floating upside down in a field of blue bubbles. Yet in a series from 2021 the head of stag gains an uneasy anthropomorphism. One particular work from the series captures the stag merely in narrow red lines. It is only almost there, and yet its face seems to call for empathy.

There is much Sturm und Drang in these works: cows cut in two, stark forests, shivering nudes. But as the years roll on, Baselitz becomes increasingly playful. He names works after the expected motifs they do not contain: No Eagle, No Deer, No Horse (all 2022). A trio of enormous crimson linocuts from 2002 feature judiciously placed white dots that cover the organs of procreation. There is also tenderness. One highlight is a 1992 etching and quiet series that depicts sleeping dogs. Rather than upside-down, these are seen at 90-degree turns, so that the dogs gain a human-like vitality.

Georg Baselitz, Silence, 2005-6.

Linocut. © Georg Baselitz. Photo: Jochen Littkemann.

The later works on show, like his recent paintings, show a stripping back – in more senses than one. A series from 2014, Without Pants in Avignon, combines etching and aquatint. It shows Baselitz’s own naked white body, crossed with wiggling black lines, floating in an amber field. While the painted series they are based on featured expressive bursts of colour, here there is a starkness that makes the artist’s own frailty all the more apparent. Tittel writes: “His prints have come to resemble boiled-down manifestations of the painterly inventions which have come before.” A Life in Print shows a great artist in his most concentrated form.