Gilbert & George, Fates, 2005. 54 digital prints on paper with ink, 167 11/16 x 299 3/16 in (426 x 760 cm). © Gilbert & George. Courtesy White Cube.

Hayward Gallery, London

7 October 2025 – 11 Jan 2026

by JOE LLOYD

Gilbert & George hate music. They once described it as “the enemy”. They even changed their nightly dining spot after they noticed the cables for a speaker that was being set up. Yet their new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, which gathers their major works since the turn of the millennium, is one of the most cacophonous exhibitions in recent memory. There is no sound, but the wildly clashing colours, coruscating patterns and lurid imagery of the venerable duo’s vast compositions seem to blip and blare like machines in a seaside arcade. In shopping malls, architects use multiple light sources to force visitors’ eyes to shift around from window display to window display. Ensconced in Gilbert & George’s hallucinatory funfair, I sometimes wanted to find a white wall to shield my eyes from the visual overload.

Gilbert & George’s Magazine Sculpture, first displayed in a black-and-white, censored version in Studio International, May 1970, Vol 179 No 922, pp 220-221. © Studio International Foundation.

I sense Gilbert & George would want it that way. The pair have been provocateurs since they appeared at the tail end of the 1960s. An early self-portrait was entitled George the Cunt and Gilbert the Shit, the words floating over their toffish outfits. At about the same time, they took to covering their skin in colourful powders, standing on a table and singing the popular 1930s song Underneath the Arches for hours at a time. The very fact that these two men, one from Devon and the other from South Tyrol, Italy, spent every waking hour together, always dressed in the suits of a bank clerk, was in itself a provocation. Some of their early works, such as the charcoal drawing series The General Jungle or Carrying on Sculpting (1971), remain milestone works of contemporary art, fusing expressive draughtsmanship with lightly philosophical texts. Emerging at the high point of dry conceptualism, the whimsy and Romanticism of these works helped show that a different – and more publicly accessible – path was possible.

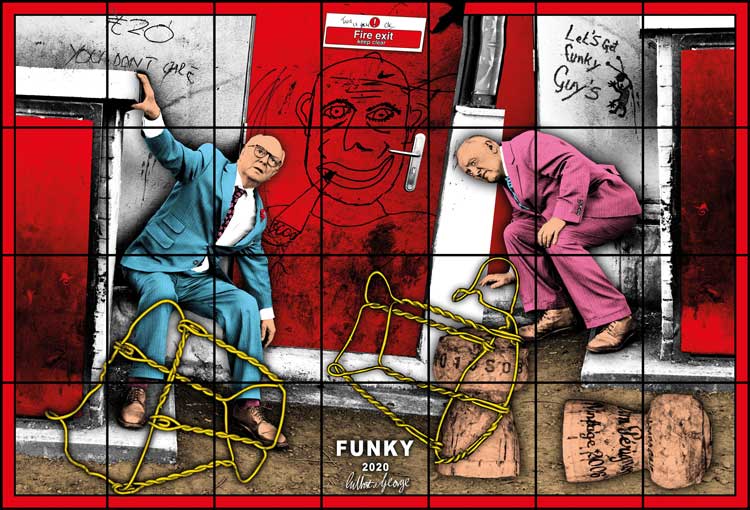

Gilbert & George. Funky, 2020. Mixed media, 118 ⅞ x 174 13/16 in (302 x 444 cm). © Gilbert & George.

Around the same time, they commenced The Pictures, the series that has dominated their output in the decades since. All feature self-portraits of the artists, usually in their suits. Working in their kitchen in Spitalfields, east London, they created a process whereby they would arrange negatives and expose them on to photographic paper, which was then developed. Many such panels are then placed together into a sort of collage, with the black framing of each unit making them resemble vast windows. The initial works were black and white, before they started hand-colouring them, giving them jewel-like colours redolent of backlit stained glass. While the earliest Pictures reveal their origins in photography, with the assemblage of panels clear, they quickly became more complicated. They also became more subversive, and sometimes more vulgar. Take Naked (1994): here, the pair bear their buttocks and genitalia while their detached floating heads stick out their tongues, all arranged around a turd-coloured totem pole of penises.

Installation view, Gilbert & George: 21st Century Pictures. Photo: Mark Blower. Courtesy of the Hayward Gallery.

At the turn of the millennium, a dystopian theme became more prominent. One pivotal work (not in the Hayward show) was MM (2000), an enormous triptych that featured brutalist buildings on the Thames, obscene graffiti, adverts for – largely not English – sex workers, and closeups of London streets named after foreign places. It connects the duo to a brand of reactionary satire with a long history in British writing and cartoons. But there is an ambiguity, even an apathy in the artists’ tableaux of broken Britain. Twenty-Eight Streets (2003), one of the earliest works featured in at the Hayward, depicts the names of streets in the duo’s postcode on a dreary dark background, with the very much living artists depicted as ghosts. The letters G and G appear in blackletter, joined not by an ampersand but by a pubic louse. Is this a wake for a lost London or are Gilbert & George themselves insects crawling over the fallen city?

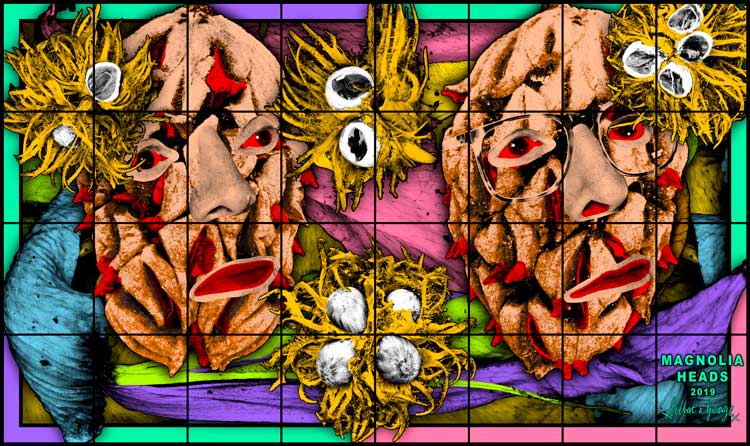

Gilbert & George. Magnolia Heads, 2019. Mixed media, 118 ½ x 198 13/16 in (301 x 505 cm). © Gilbert & George. Courtesy White Cube.

In 2003, the duo started using computer technology, which gave them greater freedom. A selection of works from the religion-mocking, science-fiction evoking Sonofagod Pictures (2005), feature saturated colour and an almost overwhelming pile-up of images that sometimes resemble bytes from an 8-bit computer game. God Save the Beard (2016) sees the two stand over a bed of profile faces like those on coins or in medieval glass windows, an effect that feels genuinely trippy. Computers also allowed them to work at scale. The present exhibition, massive as it is, features only a fragment of the total.

One series, London Pictures (2011), contains 292 separate compositions. These feature tabloid headlines written out in the same format, with a keyword – an enormous example here uses “Murder” – highlighted in red. So, we have “So Solid Star Jailed for Murder”, “Dando Murder Appeal Anguish”, “Hammer Murder Trial – Verdicts”. There is sometimes the hint of developing narratives. A jogger is murdered in one panel, then a suspect is quizzed in another. Although newsprint seems an anachronism in the scrolling age, these works capture something of our times, the relentless barrage of grim news stories that turns real lives into penny dreadfuls, pored over for a moment and then supplanted by the next grim thing.

-Gilbert-and-George.jpg)

Gilbert & George, Heterodoxy, 2005. 125 3/16 x 178 3/8 in. (318 x 453 cm). © Gilbert & George. Courtesy of Gilbert & George and White Cube.

While older works tended to feature the duo as wholes, in the 21st century Gilbert & George have increasingly morphed their own bodies into strange new forms. We see them in the form of insectoid faces, cubist deconstructions, green men, dancing skeletons, bearded pygmies and balaclava-wearing hooligans plastered with the sort of stickers one finds in the gents. The Hayward notes that some of the later works deal with the ageing process, and we see the two men surrounded by bones and lying together eyes closed as if in a coffin, and elsewhere reincarnated into the natural world, as with the tender Bed-Wetting (2019), which has some of their most ravishing imagery in its blown-up fallen leaves. It could almost be a return to their early Romantic tendencies.

-Gilbert-and-George.jpg)

Gilbert & George, Ha-Ha, 2022. Mixed media, 74.8 x 88.98 x 1.5 in (190 x 226 x 3.81 cm). © Gilbert & George. Courtesy the artists and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London.

These are exceptions in an oeuvre that tends towards the embittered. Behave (2014) sees the two as dismayed and disapproving Norman knights looking down over an antifascist shooting a sling and the text from a signpost in the City of London announcing a “Good Behaviour Zone”. The pair might be simply showing what they see on their walks around the East End streets. Their London largely cuts out the good parts, the things that draw people to live there. It is a hellish stew of prison bars, piles of scrap, discarded nitrous oxide canisters, drug baggies and all-pervading graffiti, the sort of images used as pretexts for demolishing housing estates. These subversives appear to be reactionaries. This might be a brave position to take in the art world. But it is one that makes me long for a spot of hope.

-Gilbertand-George.-Courtesy-of-Gilbert-and-George-and-White-Cube(3).jpg)

Gilbert & George, Sex Money Race Religion, 2016. Dimensions variable. © Gilbert & George. Courtesy of Gilbert & George, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris and White Cube.