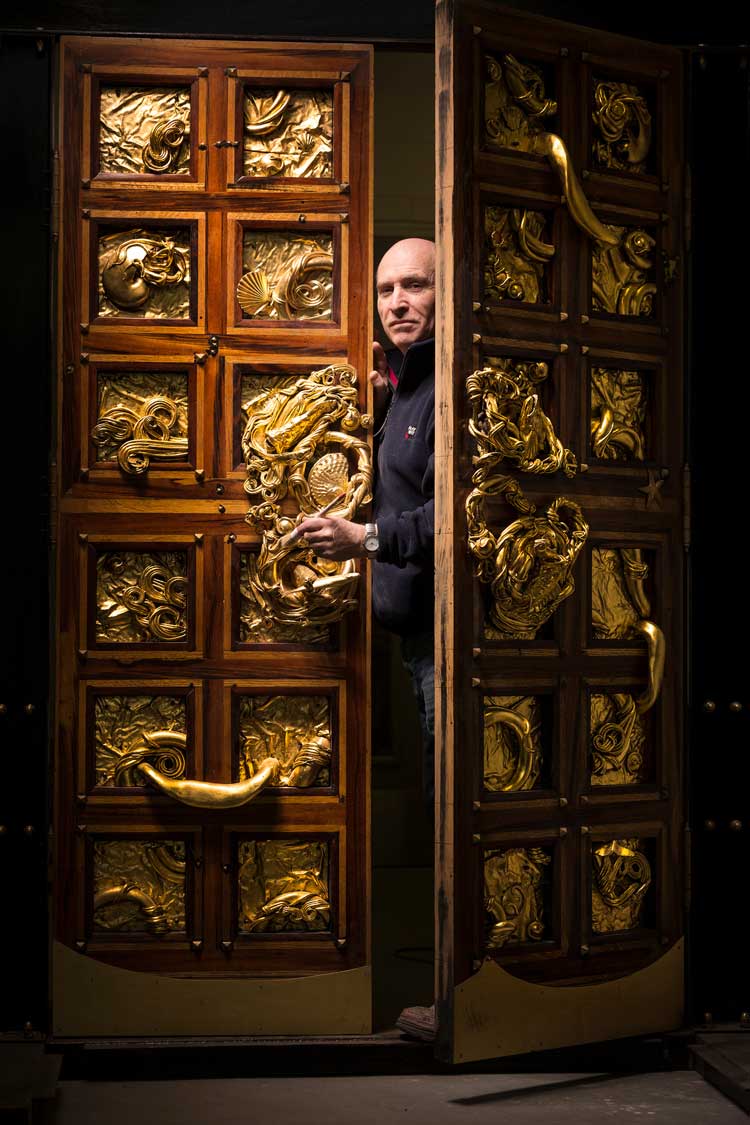

Andrew Kinghorn, Madonna. Bronze, wood, steel 2.5 x 1.7 x 1.2m. Photo: James Glossop.

by JANET McKENZIE

The British sculptor Andrew Kinghorn was born in 1951 in Hong Kong but was educated in the UK at the Dollar Academy in Scotland and then Chelsea School of Art. He found the mood that accompanied the political turmoil of London in the early 1970s depressing: the miners’ strikes of 1972 and 1974, the three-day week, food shortages, four general elections, a state of emergency in Northern Ireland, and bombings on the British mainland by the Provisional IRA. Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Structural Anthropology fuelled Kinghorn’s interest in non-European culture, in visual and cultural terms and, like many British of his generation, Kinghorn migrated, in 1974, to Australia, where he stayed for 18 years. During that time, he travelled extensively within Australia and Asia, with extended periods in Sumatra, Thailand, Burma and India. He travelled overland through Asia to Europe before returning to Australia in 1982. Australia in the 70s was also subject to political turmoil, marked by the dismissal of Gough Whitlam’s Labor government by the governor-general in 1975. In effect, Whitlam’s innovative policies on the arts, education and Aboriginal rights were defeated by conservative forces. Being British in Australia in this climate may not have been hugely popular, yet key creative individuals celebrated their freedom from the gloom of London and contributed massively to Australian society and culture.

Andrew Kinghorn, Wayside Cross for a Warzone, Bronze, steel, 5 x 1.75 x 1.5m. Photo: James Glossop.

A significant number of British artists and curators migrated to Australia in the 70s, and they took with them an appreciation and awareness of the work of the School of London artists (including Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff), and exerted significant influence through teaching positions and curatorial roles. They found the burgeoning Australian art scene particularly exciting. The curators Nick Waterlow and Tony Bond, the sculptors Hilarie Mais and Anne Graham, and the painters John Walker, John Wolseley, John Beard, Andrew Antoniou, Peter Booth (who represented Australia at the Venice Biennale with his neo-expressionist large canvasses), Michael Esson, Graham Fransella and Nicholas Harding all contributed to art education and practice in Australia.

‘I treat my work as my own personal cosmology where each work is an expression of the mental worlds I have inhabited’

The establishment of the Sydney Biennale in 1973 provided manifold opportunities for the navigation of international cultural activity. A revisionist narrative of 20th-century art that challenged New York’s hegemony as the international art capital was asserted with vision and originality. Through the 70s and 80s, the Sydney Biennale became an international showcase for contemporary art that challenged Australian attitudes too. Dialogue through, and prompted by, the visual arts subsequently came to play a key role in addressing issues of national and international significance. Aboriginal art was presented within an international context for the first time.

Andrew Kinghorn, In the Shadow of the New Republic, 1982. Bronze, steel, wood, 2.5 x 4.5 x 4.5 m. Photo courtesy the artist.

For Kinghorn, Australia provided great opportunities, where experimental culture was encouraged, due in large part to the Sculpture Triennials. The Mildura Sculpture Triennial ran from 1961 to 1978, when it evolved into the Australian Sculpture Triennial in Melbourne in 1981, 1984 and 1987. It was an unprecedented initiative that enabled extensive and diverse showcasing of experimental works, earthworks and landscape art, across various venues and institutions. Kinghorn’s audacious installation In the Shadow of the New Republic (1982) shown at the Second Australian Sculptural Biennial in 1984 is a complex work that operates on several levels. Conceived in response to personal distress and disillusionment, the scale and ambitious structure convey the verfremdungseffekt of a Brechtian theatrical piece. Alienation and deep conflict are presented to define a paradoxical, existential stance. The artist cites Francis Bacon and George Orwell as the inspirations for the dystopian piece. Just as Bacon achieves an unexpected affirmation through the choice of formal language – the precision and care applied to the creative act, Kinghorn’s placement of each human or animal figure, the respective crafted materials, achieves a lasting resonance and theatricality. The amplification of a personal experience to a universal message is due in large part to the dialogue he has with art from the past, and a desire to challenge the Eurocentric cultural hegemony. In 1983, the Scottish artist John Bellany, whose expressionistic, audacious paintings challenged the prevailing conceptual or abstract work in Britain, was invited by the Dean, John Walker, to spend a year at the Victorian College of the Arts, in Melbourne. This was a febrile moment for young artists that led to work of great commitment. In 1983 and 1986, Michael Spens, then editor of Studio International, published two special issues dedicated to the buoyant art scene in Australia.

Andrew Kinghorn, Self Portrait whilst Manic. Bronze, 59 x 36 x 36 cm. Photo: Robin Gillanders.

Although Kinghorn does not experiment with theoretical notions such as the deconstruction of the picture plane, in precise terms, In the Shadow of the New Republic employs a range of formal devices such as framing within the picture plane, images within images, thoughts layered within any given context, drawn from personal experience but alluding to universal suffering. It is a theatrical declaration, and an overlooked work of distinction.

Kinghorn worked in the building industry in Australia and then in architectural practices at a time when the relationship between architecture and the visual arts was given a massive injection of funds by the Australian government for The New Parliament House, Canberra (1988) designed by the architect Romaldo Giurgola. Work on the project began in 1981; one of the ramifications was the elevation of art’s importance to public life. This, the first scheme with an arts budget of 0.5% of total building budget, forged a unique partnership of art and architecture and contributed to a growing confidence of artists. Kinghorn’s sculpture training was transferrable to architectural projects and, in turn, working with architectonic space gave him the confidence to work in an uncompromising manner. He was then appointed lecturer at Deakin University.

Andrew Kinghorn, Self Portrait as Dr David Kelly. 170 x 100 x 70 cm. Photo: Robin Gillanders.

Kinghorn’s diverse practice has been characterised by dualism, religious belief systems and ageing. While his choice of traditional materials – bronze, aluminium and stainless steel – might align him with a traditional role of sculptor, he has interrogated cultural meaning with an iconoclastic modus operandi from the early 70s. In the Shadow of the New Republic, created in bronze, carved wood and steel, presents a haunting presence within a stage that is a metaphor for human society. Forty-three years on, Kinghorn mostly makes beautifully crafted small tableau, where cast forms of teacups or rice bowls assert the individual pitched against societal forces, the unbearable state of world politics, personal anxiety in the world of immense threat and horror.

Studio International visited him at the Edinburgh Sculpture Workshop and his house in Portobello, Edinburgh.

Janet McKenzie: How do you think growing up in Hong Kong established your life-long interest in art and culture, religion and spirituality?

Andrew Kinghorn: I was born in Hong Kong in 1951. My family had deep roots in China, having been traders since the 1870s. My father was a colonial civil servant who was responsible for the New Territories and the world I lived in was a very privileged one. We lived in large colonial houses with servants, where lunch picnics and clubs played an important role in our social life.

I have a much more positive view of colonialism than seems to be the received wisdom these days. Hong Kong was a very cosmopolitan and exciting city that was growing at an extraordinary pace. By contrast, China was riven by the huge social dislocations of Mao’s Cultural Revolution, and the former glory of its civilisation was rather diminished. Hong Kong, on the other hand, had retained much of the traditional cultural values and, thanks to the colonial administration, had a “free market” and a laissez-faire attitude to commerce.

It was not just the exquisite shape of a porcelain tea bowl I fell in love with, but the extraordinary energy with which Hong Kong was forging a new world. It was such a contrast to Britain of the 50s and 60s.

Andrew Kinghorn, Muse in a Japanese Garden. Bronze, stainless steel, antique red coral, 22 x 45 x 18 cm. Photo: John McKenzie.

The Chinese culture I first came into contact with was the cuisine. Then it dawned on us just how exquisite Chinese design was. It was not just the extraordinary craftsmanship and ingenuity when making things, but the underlying shape of things. The western things we had were characterised by an absence of sophistication whether they were cars or contemporary fashion. Everything seemed too assertive, and everything screamed NOW! But handling a piece of porcelain or jade induced completely different emotions, feelings like timelessness and peace. This was reinforced by staying at the Buddhist monastery at the top of Lantau Island. I remember being impressed by the simplicity of the monks’ lives.

JMcK: You worked together with John Wolseley, who migrated from England to Australia at about the same time as you. He has devoted his art practice in Australia to the land and to a non-western worldview. What did you learn working together?

AK: I worked with John at Deakin University for two or three years in the late 70s. John arrived at Deakin in a beaten-up Volkswagen, which I seem to remember was also his home for a while. The engine compartment was used to dry out the most exquisite small birds that he found beside roads and had been killed by passing cars. When he arrived, he had just come from the Aboriginal community of Papunya, north of Alice Springs. He was full of enthusiasm for Central Desert iconography.

We worked on a second-year student project, together with James McCaughey of the university’s drama department, that juxtaposed Aboriginal iconographic systems with contemporary Australian advertising iconography. It was fun and the students really loved John’s English upper-crust accent paired with a very easygoing and relaxed personality. John’s research interests were very different from mine as he sees himself as an explorer of landscapes and is deeply involved in wildlife and the health of ecologies. I learned a lot from John, and he was interesting to be around.

Although I travelled a lot through outback Australia visiting Aboriginal sites, I found visiting Aboriginal communities very difficult. One needed a permit, yet it was near impossible to get a reply when applying for one. Visiting outback sites where the Indigenous community had long since died out or had been relocated by government diktat became very depressing. Visiting a site was like going to a funeral and finding that you were apparently the only mourner. It became increasingly clear to me that I needed to investigate societies that had less contact with the west.

Andrew Kinghorn, Exploded Head. Bronze, 58 x 36 x 36 cm. Photo: Robin Gillanders.

JMcK: What prompted your extensive travel in southeast Asia in the 70s and 80s? What impact did it have on you as an artist?

AK: I decided to investigate some of the cultures of Papua New Guinea in 1976. It had just declared independence from Australia. The first tarmac road into the Highlands had been built and my first wife, the gallerist Andrea May Churcher, and I decided to split our time between the tribal areas around Mount Hagen and the communities on the Sepik River in the north of the island. We were like children in a sweetshop, and it changed us both for ever. Unlike the west, where in many senses there has been a homogenisation of cultural values, so many cultures existed side by side with different languages and vastly different belief systems, cultures and iconographic traditions. All were extraordinary. Travelling in Papua New Guinea was difficult and dangerous at that time. We used dugout canoes in the Sepik but, even though Andrea took anti-malarial tablets, she developed a bad case of malaria. However, despite the risks involved, what made this trip so fascinating was watching different societies competing with each other to produce architecture, artefacts and iconography that were distinct and unique. The sheer diversity of human expression was addictive to us, and it started a series of pilgrimages to south-east Asia that lasted many years. Notable trips included time spent living in long houses among the Batak people of Sumatra and a Dayak community on the Mahakam River in Kalimantan. I have seldom been happier and, despite the language barriers, I have seldom learned as much.

Later, we spent a little over a year travelling overland from Australia to the UK – a great rite of passage for Australians in those days. I have derived so much in my life from travelling. First, in the realisation that we are fundamentally all the same under the skin and all of us adjusting ourselves to the landscapes and environments we live in while simultaneously building a mythology and cosmology that places us somewhere within that world. Second, that as a species we are extraordinarily inventive – irrepressibly so.

The experiences I had during those years have had a profound effect on my life as an artist. It is not that I have ever pillaged imagery from other cultures, but I treat my work as my own personal cosmology where each work is an expression of the mental worlds I have inhabited. When I make a sculpture, I want to produce a miniature world that will stand up on its own and that is distinct from the last sculpture and from the one to come. It has led me to work across genres from topics involving politics, work culture, growing old, images of people close to or inspirational to me, for example images of my wife. I have also made images that concern my musings on the Divine.

JMcK: There are numerous architectural elements in your sculptures – the grid structures that allude to the home and to the family, and they can be seen to operate as metaphors for one’s spiritual journey. Can you describe your work with architects and how that work informed your practice?

AK: Although I was very familiar with high-rise buildings from my youth in Hong Kong, the buildings were mostly standard tower blocks influenced by Mies van der Rohe. But it wasn’t until my family came “home” to London that I first saw architecture that was designed to inspire awe in the viewer. Ironically, what I found more interesting were the pockmarks from bombs dropped during the war. More than anything else I am aware that architecture is an illusion of stability, an illusion that can be shattered by natural disaster or warring states. Indeed, in my early life I was made very aware of the fragility of life. After all, I was born six years after the explosion of the first atomic bomb. There was plenty of evidence of war in Hong Kong, from abandoned pillboxes to the skull our gardener discovered while digging a flowerbed that turned out to be result of the beheading of a Chinese “looter” by the Japanese!

Two things that stand out from my youth are visiting Rome and Pompeii: in Pompeii, of course, how sudden catastrophe can envelope a city; and in Rome how one city sits on the ruins of a previous city. That sense of the transitory informs a lot of my thoughts about architecture.

I first visited Rome with my parents when I was 10 and remember being overwhelmed by the scale and sheer theatricality of St Peter’s [Basilica] and the Colosseum. There is an underlying geometry to the buildings, but it is the starting point for the articulation of a space that has layer upon layer of meaning to it.

You have very perceptively recognised how important the use of the grid has been to me. I see the grid as a means of fixing something in place, but as I have grown older, I have become more interested in subverting the geometry of things as well as trying to loosen the notion of permanence of buildings. On a poetic level, I am much more attuned to the romantic poets who often found beauty in decayed and neglected ruins. Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey springs to mind as does Shelley’s Ozymandias.

My own first tentative steps in the architectural world were with the inspirational Australian architect Nonda Katsalidis. We were both approached by the Arts Victoria to be involved in a project entitled Working Together in Architecture. Together with other artists/craftsmen, we worked on the proposed rescue of an early Melbourne church that had been partially demolished by a developer. The idea of involving artists in the design of a building at the early stage of development was revolutionary. The proposals we worked on were very good, but sadly they were never realised. I then worked for a while managing the CAD system of the architectural practice Alexander Metherell in Melbourne.

Experiences like these, together with later experiences in the financial sector gave me the confidence to buy and redesign and refurbish historic buildings in Edinburgh.

Andrew Kinghorn, Anthropomorphs. Bronze, stainless steel, largest of the 15 = 340 x 90 x 45 cm. Photo courtesy the artist.

JMcK: You have also interrogated western mythology, and it forms the basis of many of your works. Can you describe your relationship with western culture, particularly in your series Anthropomorphs (2019-21)?

AK: I started making Anthropomorphs as a way of expressing an admiration for the way in which mankind invents belief systems and then evolves them into something different. Everything is in a state of evolution except the movement seems so slow sometimes that we most often do not notice it. I envisaged making a room full of different manifestations of the sacred. They would be sort of totem poles and I was interested to know whether, when they shared a common space, they would sit together harmoniously or whether they would fight. I resolved to make the objects from stainless steel and bronze.

I started by making an image of the pre-Christian god Baal. Baal was a fertility god depicted as half bull, half man. I concentrated on depicting the head and horns of the god. From there, I depicted female images of divinity by making three images concentrating on notions of feminine beauty. Then I made an image of a cornucopia in the form of a large bronze antique suitcase. Then I worked on an interpretation of the Winged Victory of Samothrace. I tried to capture the sense of flight and momentum. The finished work was aluminium wings bearing aloft a bronze anvil.

I found an old, weathered piece of wood that exemplified the Zen notion of “isness”, and a single bull’s horn that had a pattern of growth where the gradual increase in girth, together with a spiralling shape, followed a mathematical principle much like the Fibonacci sequence.

The work just suggested itself to me and culminated in 15 separate works. I asked friends for a response, but found, rather alarmingly, that very few of the origins of the work were clear to people who looked at them. But the works did trigger affirmative responses, so I have rather taken ambiguity as a positive. The work serves as a Rorschach test where the viewers response tells them most about themselves.

JMcK: The use of a tableau conjures quotidian ritual: meals, toys and the bits and bobs we accumulate; they are also small-scale stages on which life is performed, immortalised in your case with a Baroque theatricality. Can you explain these works?

AK: I started working with tableaux several years ago when I was working on a series of portraits. I thought that realistic heads didn’t really communicate enough about a person since most of us can be defined more accurately by the possessions we collect, the houses we live in and the stuff we aspire to own.

Andrew Kinghorn, Portrait of Alison. Stainless steel, bronze, 150 x 40 x 40 cm. Photo: John McKenzie.

I started making portraits of my parents and then my wife, the poet, Alison Campbell. From there, I extended the idea of objects to trying to define a feeling – for instance, the feeling of abandonment I had when I found myself completely lacking in inspiration. Strangely enough, making a sculpture about that emotion of despair was cathartic and kickstarted a new series of works. These works triggered a shrinking of scale since I realised that the obvious home for the portraits was that of the person depicted and the size of the respective people’s homes determined the scale. Since then, the scale of my work has shrunk further, and I am now happier working towards fitting my work on a mantlepiece or a bookshelf.

Andrew Kinghorn, Portrait of my Father. Bronze, steel, copper, 50 x 80 x 40 cm. Photo: John McKenzie.

JMcK: Madonna (1984- ) is by contrast monumental, using the symbolism of the doorway to link the secular to the spiritual. Can you explain your preoccupations in this significant piece?

AK: I started making Madonna 40 years ago and it is still not finished and has never been shown. Madonna had a very unpropitious start. I discovered that a friend had salvaged an industrial oak vat from a whisky firm that had gone bankrupt. The whisky was at the very lowest end of the market. Luckily, I managed to obtain several 4in x 8in staves. I wanted to transform wood that had once induced despair to something that inspired hope!

Initially, I decided to produce a freestanding doorway that would act as a liminal and transforming space. I had recently returned from Spain and became fascinated by both domestic and religious doorways, so I bought some bronze components that included hinges and studding. A little later, in the Boqueria market on the Ramblas in Barcelona, I came across a fish stall where there was such a density of fish stacked up, it almost felt as if they were a shoal swimming towards you.

Andrew Kinghorn, Madonna. Bronze, wood, steel 2.5 x 1.7 x 1.2m. Photo: James Glossop.

So, I married the geometry and structure of door construction with the chaos of writhing fish. Not just any fish but fish as the symbol for Christ. I have never had an experience of religious conversion, neither am I a “good” Christian since I am far too selfish, and I have always had doubts about doctrine. Most significant is my scepticism about the immaculate conception, but I have no doubt how important Christianity is to the development of European civilisation. Despite this, I resolved to make a Christian sculpture that involved my personal thoughts.

The Madonna stands between one world, the world of the violence and retribution of the Old Testament, and the other world, the enlightenment of the New Testament. Not only did I want the Christian imagery to overwhelm the underlying grid of the door, but I wanted to suggest that we are, each one of us who follow the path, participating in Christ. This sculpture is still “missing” something, but I am not sure what. Perhaps my reluctance to show it has something to do with my own religious uncertainty. Or perhaps I am still not sure of the context I want to show it in. I envisage this sculpture floating on several tons of pea gravel.

JMcK: Your Muse series is a testament to the creative life and those who have inspired you and nurtured your practice. The small sculptures are replete with references to art history, cultural rituals, food, the everyday, to poetry and to love. How did this series evolve?

AK: I started working on Edinburgh Muses: Six Goddesses of the Arts during the first Covid-19 lockdown when I was not able to work in my studio building. The inspiration for the work was a desire to thank people who have made a positive contribution to my life.

For many years, I have visited our National Galleries of Scotland with their wonderful collections. It goes without saying that their staff are extraordinary, but little attention is focused on the volunteers who help the gallery tick, among whom is my wife. I chose to make six sculptures in total, five from the Friends Advisory Committee and one member of staff, a curator and scholar who has been particularly supportive of the friends and their aims. I wanted to make little sculptures that celebrated their qualities, and also, acted as a thank you.

The “thank you” took the form of individual rice bowls which I immortalised in patinated and gilded bronze. These were placed on bronze cloth and then joined with objects which described an aspect of their life.

A little later, I wanted to celebrate my wife, whom I have known and been in love with since we were 14. If ever I have had a muse, it is she and if one rice bowl signifies thanks then immortalising her long-term fascination with Chinese tea bowls denotes the greatest thanks.

Similarly, I celebrated Alison’s beautiful poetry with another larger scale sculpture of selected work, CNC-cut [computer numerical control-cut] into stainless steel and powder coated. Some time ago, I was asked why all my muses were female. I do not really have an answer to that. I am also in debt to many men, but I cannot ever conceive of making something inspired by them. Although I might give a man a sculpture if I like them but if I feel in debt, I generally respond with a gruff: “Thanks!”

Andrew Kinghorn, Shrine. Bronze and stainless steel, 24 x 43 x 22 cm. Photo: John McKenzie.

JMcK: Can you explain how the essence of materials plays a powerful role, in all your work, particularly in Shrines?

AK: I have always been curious about wayside or household shrines. They seem to be a near universal expression in southeast Asia and India and once played a more important part of European life going back to before the Romans. They have always induced quiet reflection in me, and I like the sense of a shrine is a sort of special place that is apart from the hubbub of the everyday.

Andrew Kinghorn, Shrine. Carrara marble and bronze, 65 x 45 x 15 cm. Photo: John McKenzie.

I intended my shrines to be small and modest visual poems which concentrated on the subtle differences between objects and materials. My shrines do not really mean anything. I am not trying to make a point or push an agenda. They are simply a product of gentle musings.

JMcK: How did your Neo-Cubist Family evolve?

AK: Neo-Cubist Family was inspired by my friend Louise Brodie. Louise has three brothers but is the only girl in the family. I wanted to make a sculpture that was a small portrait that celebrated her uniqueness. The quote on the front of the sculpture is derived from Cézanne’s quote: “Everything in nature is formed upon the sphere, the cone and the cylinder.” It has always mystified me that the cubists venerated Cézanne so much, despite the fact that he omitted the cube, from his recipe of shapes.

Andrew Kinghorn, Neo Cubist Family. Bronze, aluminium, stainless steel, gilt brass, 18 x 22 x 12 cm. Photo: Oana Stanciu.

I made a sculpture celebrating the absence of the cube by juxtaposing different metals (brass, bronze, aluminium and stainless steel) with a semi-precious stone of a cubist-like shape. I wished to embrace diversity. I made three of these little sculptures that could apply to different situations. Neo-Cubist Family is a very simple sculpture and the way it was made appeals to me. I am nearly 75 now, and I am much more interested in beautiful objects than I once was. I am no longer interested in conceptual art if it doesn’t culminate in an object that can hold its own independently. And so few do.

I am also less drawn to politics or conflict than I was when younger. I suppose as one gets towards the end of life, the legacy one wants to leave behind is positive and affirmative. If there is one topic that has a fascination for me now, it is the extraordinary persistence of love.