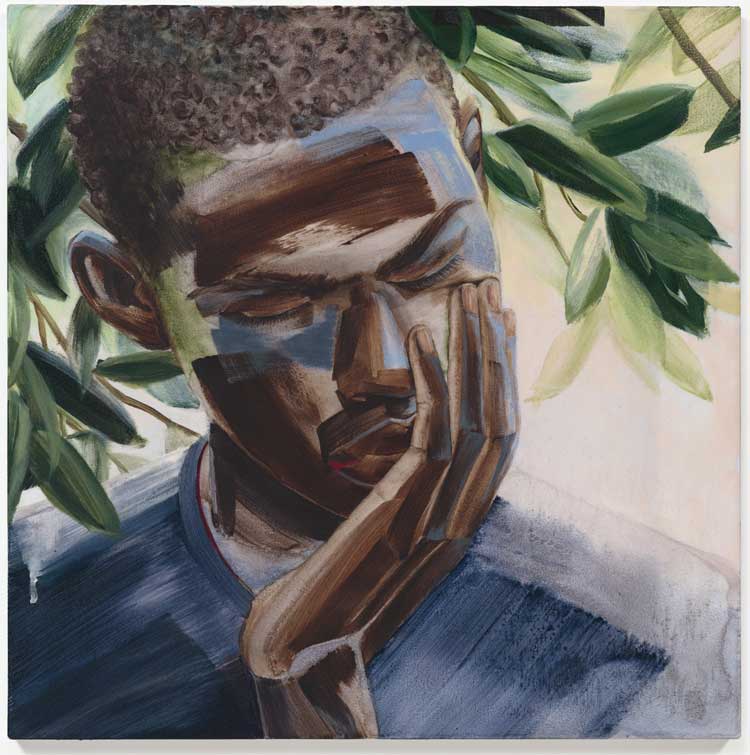

Ali Eyal, And Look Where I Went, 2025. Oil on linen. Courtesy of the artist. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Sarah Golonka.

Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, various venues

5 October 2025 – 1 March 2026

by JILL SPALDING

For reasons not made clear, this edition is a departure. As had been the tradition, it’s not themed. Surprisingly, too, as co-curated by Essence Harden (hailing from Frieze Focus) and Paulina Pobocha (from the Art Institute of Chicago), only 28 artists and collectives were selected, down from 39 in 2023, allowing for a more generous presentation but drastically narrowing a burgeoning field.

Also baffling, unlike past iterations’ pound-the-pavements scouting for leads to underexposed artists, many, such as Pat O’Neill (at 86, the oldest artist here), have a provenance – fallen from headlines but long shown in galleries and museums. Oddly, too, although the youngest presented, Ali Eyal, is 31, and several of the entries involve mixed media, none incorporates artificial intelligence, which was joined to the palette at the Museum of Modern Art in New York three years ago by Refik Anadol’s commanding Unsupervised.

Pat O’Neill, Safer than Springtime, 1964. Fiberglass, aluminum, steel, paint. Courtesy of the artist and Philip Martin Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Patrick Martinez, Hold the Ice, 2020. Neon on plexiglass. Installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Jill Spalding.

Most unexpectedly, in a world that’s exploding, this is a calm exhibition. For the most part, it stays clear of politics. There’s a plastic neon-signage work lettered ICE, referencing the US’s Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, by Patrick Martinez but it’s small and placed too high to enrage. And a revisited commentary on betrayal wrought of lacquered wood and monitors by the storied Japanese American artist Bruce Yonemoto that frames the horror of his family’s wartime internment as revised history. There is one assaultive installation, given its own alcove – a harrowing group of Mike Stoltz’s pounding four channel videos flashed with pulsing optical illusions which, warns the caption, can trigger epilepsy!

Sound verges on deafening in a boisterous performance piece by Michael Donte’s Black House/Radio – animated as on his streaming platform by Black DJs urging visitors to light up the dance floor, and leave the less mobile to lounge on sofas.

Brian Rochefort, Haze, 2025. Ceramic, glaze, glass fragments. 20 × 21 × 22 in. (50.8 × 53.3 × 55.9 cm). Courtesy Sean Kelly Gallery. Photo: Marten Elder.

The most memorable works, nonetheless, are quietly accomplished. Such are Brian Rochefort’s wondrous sculpted pots, incised, painted, glazed and wrested into miniature worlds; O’Neill’s astonishingly contemporary polished sculptures from the 1960s, crafted from industrial materials such as resin and fibreglass and flourished with amusements extending to pickles and fur; Kelly Wall’s eroding amusement-park artefacts wrought from ceramics, metals and wood into stands holding powdered-glass postcards stained into cloudscapes, a wishing well rigged to convert pennies to copper slugs at the turn of a wheel and a grimy fountain clogged with the mugs that have all but emptied it.

Work by Kelly Wall, installation view, Made in L.A. 2025, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Sarah Golonka.

Outstanding, too, Carl Cheng’s conceptual compositions of elements ranging from sand to hi-tech tools given context in bespoke wooden boxes, and his strangely beautiful composite of circuit boards joined to suggest crop fields as viewed from a plane; Widline Cadet’s arresting steel-framed, glazed ceramic pinwheels depicting a fragmented palimpsest of the flora and family photos that marked her Haitian childhood and images of relocation to Southern California which, were they set in motion, would portray a full life; and an ethereal installation, Suggunga (Hello; 2024), by the interdisciplinary Korean American artist Na Mira, built of a suspended strobe-lit slab of holographic glass that comingles analogue and digital images drawn from ancient tales and memories with the happenings at one end of the room reflected back to viewers at the other end.

Greg Breda, Here Am I, 2025. Acrylic on polyester canvas. Courtesy of the artist and Patron, Chicago. Photo: Brica Wilcox.

Painting features strongly at the entry with (Eye on ’84), the collaborative tripartite mural first seen on Freeway 110 that features symbols of harmony in anticipation of the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, by the late Alonzo Davis (he died in January); and with Greg Breda’s stunning portraits that engage Da Vinci’s dictum, “relief is the heart and the soul”, with broad strokes of shaded blacks forming a limb or lighting half a face on a canvas detailed with florals soft as silk.

Most impacting is Eyal’s surreal landscape within landscape, And Look Where I Went (2025), a wall-length oil-on-linen painting that conflates the trauma of vendors stranded amid the singed detritus the artist encountered minutes after the Twin Towers collapsed with his recall of the devastation he had experienced in Iraq – further charged with the angst that Angelenos are experiencing now.

Gabriela Ruiz, Collective Scream, 2025. Acrylic, gouache, pastel, coloured pencil, acrylic pens, epoxy clay, metal hooks, metal pipes, metal hardware, LCD monitors, TV monitor, roll-up gate, LED streetlamp, and surveillance camera on wood panel. Courtesy of the artist. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Sarah Golonka.

Interdisciplinary work abounds; most cleverly by the self-taught Mexican American artist Gabriela Ruiz with Collective Scream (2025), a winking, interactive, wildly coloured, epoxy clay wall sculpture that addresses mass consumerism, queerism and the constant monitoring of Black communities, with TV and LCD monitors, an LED streetlamp, metal hardware and a surveillance camera; most poignantly with Battle of the City on Fire by Pasadena-born Patrick Martinez, whose searing evocation of fires involve a fractured wall composed of cinder-blocks and stucco, and neon latex and house paint on scorched panel; and most elaborately by Freddy Villalobos, whose installation, Waiting for the stone to speak, for I know nothing of adventure (2025), comments on LA’s tempestuous cultural evolution with four sculpted elements involving purple neon pedestals, limestone frescoes and a wrenchingly slow two-hour video that cruises his African-American neighbourhood to communicate the community and discord that led to a native son’s 1964 violent death.

Freddy Villalobos, waiting for the stone to speak, for I know nothing of aventure, 2025. Single-channel video, automotive paint (Cadillac Black Rose and Cadillac Black Diamond), MDF, pigment suspended in slaked lime on burlap, acrylic sheet, neon, subwoofer, chopped and screwed audio, steel, lime plaster projection screen. Courtesy of the artist. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Sarah Golonka.

None marks more strongly than David Alekhuogie’s poetically patched archival inkjet prints that fold an autobiography pieced from found images, or – as in Still Life With Okra, Corn, and Tomato (2020) – a Dutch master painting, into coated jersey cotton.

David Alekhuogie, Still Life With Okra, Corn, and Tomato, 2020. Made in L.A. 2025, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Sarah Golonka.

Alake Shilling, Buggy Bear Crashes Made in L.A., 2025. Co-presented by the Hammer Museum and Art Production Fund in association with Made in L.A. 2025. Installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, October 5, 2025–March 1, 2026. Photo: Sarah Golonka.

If biennials had a mascot, this year’s would be Alake Shilling, for the sheer joy and silliness of her 25ft- (7.6 metre) tall inflatable sculpture, Buggy Bear Crashes Made in L.A. (2025), which commands the Hammer’s Wilshire Boulevard sculpture pedestal, and her bravado try-anything ceramics glued with bits of whatever that she says “come to her in the night – or whenever”. Neither “fine art” nor sprung from whole cloth (think Mike Kelly’s reinterpreted stuffed animals, Jeff Koons’s archetypal Play-Doh, the Campana Brothers’ cuddly stuffed-animal sofas), they nonetheless blow a fresh breeze on the canon. Commenting on the inflatable, a passerby noted: “Very LA.” Right on!

To mine more gold from this season of riches, head over to Gemini for the long-stored-away Rauschenbergs pulled from its warehouses. Fragile and time-consuming to reassemble, the majority have been rarely exhibited. Such, from 1971, are the sectional Cardbirds, painstakingly reproduced on fresh cardboard with screen printing and photographic transfers from boxes found in an alley – labels, creases and all – then pieced into birds poised for flight.

Left: Robert Rauschenberg, Publicon–Station I, 1978. Painted wood cabinet with fabric collage, Plexiglas mirror, polished aluminum, with gold-leafed paddle and electric lights, 59 x 30 x 12 in (149.9 x 76.2 x 30.5 cm) all dimensions in closed position. Right: Publicon–Station IV, 1978. Wood and aluminium with baked epoxy enamel, collaged fabrics, bicycle wheel, plexiglas, fluorescent light bulb, and lacquer, overall (closed): 71.1 × 91.4 × 33 cm (28 × 36 × 13 in); overall (open): 132.08 × 162.56 × 33.02 cm (52 × 64 × 13 in). Courtesy of Gemini G.E.L. and the Artist.

All the lesser-known of the signatures – combines, screen prints, and lithographs – astound. From 1978, Publicon – Station l and Publicon – Station lV, witty framed lacquer-coated silk and cotton portraits of an oar and a wheel, present as contemporary. I was particularly moved by the deceptively elementary works, seemingly crafted to last but a day, such as LinkandHind, both from 1974, delicate abstractions fashioned of handmade stained and screen-printed tissue and paper pulp; and Hard Eight and Little Joe, ethereal 1975 collaborations from Ahmedabad, India, crafted of handmade paper/bamboo/fabric. A collector I spoke to was gobsmacked by Horsefeathers Thirteen-V, a 1972 eight-colour offset lithograph involving screenprint, pochoir, collage and embossing.

Carol Bove, Nights of Cabiria, 2025, installation view. © Carol Bove Studio LLC. Photo: Maris Hutchinson, Courtesy Gagosian.

Not to miss, at the Gagosian gallery, until 1 November, is Carol Bove’s sensational solo show, Nights of Cabiria, an ambitious reconfiguration of the entire gallery to reflect on a Los Angeles rooted in industry building from raw infrastructure to surfboard manufacturing to aerospace. Sculpted elements, tubing and reclaimed scaffolding, worked together with materials involving screen-printed scrims, weathered, painted, mirrored and crushed metals, reference both the rough and the polished, the art object and the environment, to brilliantly skew the boundaries between object and space, materials and concept, Los Angeles and dystopia.

Carol Bove, Nights of Cabiria, 2025, installation view. © Carol Bove Studio LLC. Photo: Maris Hutchinson, Courtesy Gagosian.