Amalia Pica. © Amalia Pica. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, London.

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Signals missed or misunderstood, things lost in translation, the way the meaning of an ordinary object or ritual can shift depending on its placement – all these are essential elements in the practice of Amalia Pica. Born in 1978 in Neuquén, in the north of Patagonia, Argentina, Pica moved to Buenos Aires to do a BA at the Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes PP. Then, at 24, she won a coveted two-year residency at the Rijksakademie in Amsterdam. She now lives in London. Moving so often has given her plenty of opportunities to consider how the value or meaning of something changes depending on the language, location or the lens through which it is viewed.

Pica won her place at the prestigious Rijksakademie in Amsterdam, in part thanks to her work Hora Catedra (School Period, 2002), questioning the iconography around the House of Tucumán, where Argentina formally declared independence from Spain in 1816. At that time, she was working as a schoolteacher, required to lead her pupils in elaborate recreations of this monument on Independence Day every year, and she had been struck by the fact that the building is always represented as yellow, even though it is white. Hora Catedra consisted of broadcasting yellow light across the building for 40 minutes, the time of a school period.

Amalia Pica: Keepsake, installation view, Cample Line, 4 October – 14 December 2025. Image courtesy the gallery. Photo: Mike Bolam.

In Amsterdam, she expanded her practice to explore commonalities and conflict in the collective consciousness around everyday symbols and signifiers. Bunting cropped up early – appearing in a performance work she devised for the Venice Biennale in 2011. Together with festoon lights, it also appeared in her solo show at the Chisenhale gallery in 2012. Chairs have also made a few appearances: in fact, I first encountered Pica’s work in 2016, when the South London Gallery invited its local community to take part in her public performance work Asamble, which requires local people to congregate, bringing a chair from their home, to form and then disrupt circles of gathering in public. The work explores the politics of community. And those politics resonate quite differently, across the three places it has been staged: first outside Argentina’s House of Congress in Buenos Aires, and then, in 2015, at New York’s Guggenheim Museum.

Amalia Pica, Asamble, Performance, BP.15, Buenos Aires, AR, 2015. © Amalia Pica. Courtesy of the artist; BP.15, Buenos Aires; and Herald St, London.

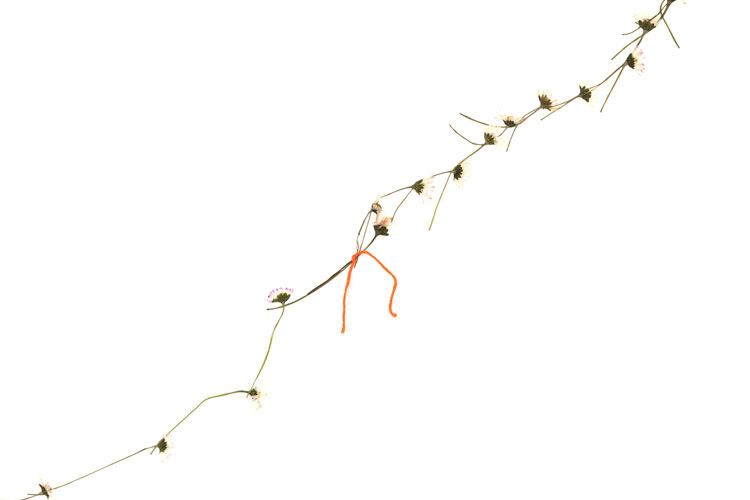

Now, Pica has a solo show of new work, Keepsake, at Cample Line in the Scottish borders. In it she features daisy chains – inspired by her five-year-old son’s discovery of this timeless, summer activity – as well as embroidered works featuring his pre-school mark-making. The show also includes 134 Years of Smoke, a film collaboration with her partner, the Mexican film-maker Rafael Ortega, inspired by a found painting at a car boot sale. Later in the autumn, she is unveiling a public sculpture – a growing strand in her work – in Bergen, Norway. Called Ribbon Dance, it is an interactive sculpture, sited outside a sports stadium, which invites viewers to turn a handle to trigger a dancing ribbon.

Pica has had numerous solo exhibitions, including at: Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, in 2024; Museo Jumex, Mexico City, in 2023; Fondazione Memmo, Rome, in 2022; Brighton CCA in 2022; Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich, in 2020; Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporáneo, Seville, in 2019; The New Art Gallery, Walsall, UK, in 2019; Perth Institute of Contemporary Art, Australia, in 2018; The Power Plant, Toronto, in 2017; NC Arte, Bogotá, in 2017; Kunstverein Freiburg, Germany, in 2016. She is represented by New York’s Tanya Bonakdar Gallery.

Studio International interviewed the artist in her east London studio before the start of her current show, Keepsake.

Veronica Simpson: I’m intrigued by the use of daisy chains in the Cample Line show. Why did this simple summer activity grab your interest?

Amalia Pica: I had never seen a daisy chain being made. I had seen representations or pictures of midsummer and people wearing them but my son was taught by another kid, at a Forest School Camp. And when he showed me how, I realised it’s like a sculptural thing: you make a hole, and put something through it, then put them together and create a chain. This is like another kind of knowledge that’s passed on.

Amalia Pica: Keepsake, installation view, Cample Line, 4 October – 14 December 2025. Image courtesy the gallery. Photo: Mike Bolam.

VS: I had never thought of that – it is a very English tradition. And you are displaying them around the walls.

AP: They are surprisingly strong once they’re dried. We got people [in Thornhill, where Cample Line is based] – some school groups, visitors, elderly groups – to make daisy chains for us. We pressed them. I did all the tests to see how we could display them in the show, and I’m now making flour paste, which I brush on the back of the flowers, and then stick them on the wall, and we join the chains together with orange embroidery thread. It’s basically a daisy chain around the entire space, and these joins are quite visible. The stalks are very graphic. It was a really nice surprise. These ideas don’t come together unless you have this level of participation. When it’s just my work, I’m way more critical. But when it’s something other people made for you and with you, you get to be proud of it in a different way. I think it looks great around the space.

134 Years of Smoke. Film still. Amalia Pica in collaboration with filmmaker Rafael Ortega. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St

VS: Your inspirations here are serendipitous and organic – your son making daisy chains, and your partner finding a painting, which resulted in the video work 134 Years of Smoke, that converses with the painting.

AP: Yes, a painting he found in a car boot sale. The painting is a bunch of British flowers, which look like wildflowers, but they are wrapped in newspaper, almost as if they have been wrapped and opened. The newspaper is [Argentinian daily] La Nación. But the painting shows the date 9 July 1891 on the newspaper, 9 July being the day Argentinian independence [is celebrated]. So, it’s one of these patriotic symbols. The painting itself is dated 1891, and the signature is Andrea G.

Amalia Pica: Keepsake, installation view, Cample Line, 4 October – 14 December 2025. Image courtesy the gallery. Photo: Mike Bolam.

I was interested in who the painter was at the beginning, but there are two more things about the name – it could be a female name if it’s Spanish, but it could be a male name if it’s Italian. There are many Italians in Argentina. I have Italian blood – an ancestor moved there in 1835. So, it’s possible that the painter was Italian. If it’s a female painter, that would be unusual at that time. Then there’s the fact that it is dated July and that makes sense if they are British flowers, but July is not flower season in Argentina.

VS: The intrigue is around where it was painted and by whom?

AP: In the beginning, but I also find the mystery of it beautiful. The painting is in this grand sort of frame, so I decided to have it cleaned, because the painting was quite yellow. But it lost some of its beauty when it was cleaned, which is also interesting. Should we have not cleaned it? But I am very interested in these impulses that come from feeling nostalgic. Is the painter making a painting here (in the UK) to honour a country there? The reason it’s called 134 Years of Smoke is because the yellow was all from nicotine.

VS: I have seen stills from the film, ethereal images of smoke.

AP: My partner is a film-maker, and this is a collaboration with him. I don’t make films. We think of it as a vignette of a work that maybe will become more essayistic in form. The video work includes shots of the restoring process, cleaning. You see closeups of the hands of the restorer, and you see this transformation and the de-yellowing. The video work is basically these two screens, one is vertical and sits lower than the other. The cigarette smoke is below and the film about the conservation is in a horizontal frame above.

VS: This chimes nicely within the context of everyday objects and how we make them meaningful, which is such a strong part of your practice.

AP: Exactly. And I’m so interested in material cultures. In a sense, it’s a more open-ended interest in still life. An object can say so many things. And maybe the intention is less for people to decipher that but just openly relate to it.

.jpg)

Amalia Pica, Keepsake #12, 2024. Cotton and wool on linen, 40 x 30.2 x 3.6 cm. © Amalia Pica. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, London.

VS: Tell me about the embroideries on linen that you have in the show.

AP: They are new, for Cample Line. But it’s a series I started maybe a year and a half ago. Because my work is so varied, there used to be more anxiety on my behalf about how things fit together, but now one of my strategies is to bring something I’m already making to meet that new space. The embroidery is quite large. It’s hand-embroidered. And there are a few smaller studies. They are based on drawings that my son made just before he started to draw “pictures”. With my background as a primary school art teacher, so much of my work was to deconstruct the way kids draw things as they think they should be: the House, the Tree. And probably their houses or trees don’t look like that to them, they’ve just learned this short cut to how to draw something. I was very attached to these pre-representational drawings, because I knew what was coming. But, at the same time, there’s this disparity between the speed of the marker – literally how little time it took him to make (the image) – but also how it moves. And then there’s this stitch, which is a very controlled action. I think they have that tension. When you see them from afar, they look expressive, but as you get closer, they are so detailed and painstaking.

These works were part of a grant from the Henry Moore Foundation so they needed to be sculptural works. I think of the daisy chain as a collective sculpture. But clearly the presence in the space is way more that of a drawing. And then the embroideries: they, again, have this painterly quality. But I think of them as time-based, because of the time it took to make them. It’s quite interesting to then look at the show and think it’s quite a two-dimensional show for the stuff I do. But there is a bronze, a junk modelling sculpture.

.jpg)

Amalia Pica, Keepsake #10, 2024. Cotton and wool on linen, 40 x 30.2 x 3.6 cm. © Amalia Pica. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, London.

I see that my son will pick up daisies and conkers but often, in a London park, his treasure is trash. And there’s all this rubbish around. I guess there’s also something about that sense of sustainability in the work. It’s not necessarily very present for Cample, but there’s obviously a zero carbon footprint for the daisies work. We even used flour paste to put them up. And then this junk modelling is a thing that you usually do with kids and then we transform that into a bronze, but we still recognise its source in the materials. It will sit wrapped in a newspaper, so it’s like the flowers in the painting a little bit. There’s the plinth, the newspaper and the bronze sits on top. There’s something about formal education, informal learning, and it all somehow goes back to the painting.

.jpg)

Amalia Pica, Keepsake #15, 2025. Cotton and wool on linen, 135 x 135 cm. © Amalia Pica. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, London.

VS: Let’s touch on your formal education, your early art practice: you studied in Buenos Aires, and then you worked as a primary school teacher.

AP: I studied sculpture, then teaching and I started teaching art to kids. In Argentina, school is still very nationalistic. [It’s] different from the UK. But it’s different for a country that was established from a certain date with a constitution, not like the UK, which evolved into parliament and monarchy. There’s a myth of origin in Argentina and it’s really perpetuated in school. As a teacher, I was the one that had to do all the sets for the Independence Day play, the reproduction of images, the propaganda. It felt very weird. We had to get them to do the design of the House of Tucumán, where independence was declared, as a backdrop for a play.

Amalia Pica, Hora Catedra (Class Period), 2002. Projected yellow light, Tucuman, Argentina. © Amalia Pica. Courtesy of the artist and Herald St, London.

VS: This inspired the work Hora Catedra (School Period, 2002), which helped you secure a place at the Rijksakademie.

AP: Yes, I was really lucky, I guess. I was 24, and the average age is 30 to 35. So, I was quite young, and that’s how I left Argentina. By the time I finished my residency, I had more things to do in the Netherlands than there, so I stayed on.

VS: Tell me some of your influences and ideas and how that changed through your time in Amsterdam.

AP: My first visual education came from theatre. My grandma was a theatre director, and as a teenager I attended a lot of theatre workshops. We were into [Samuel] Beckett, for example. I thought I might go into set design, going to art school and doing a postgraduate degree. I did sculpture because I thought there would be more of an open investigation of materials, but I was really wrong. It was very academic. By the time I finished art school, I didn’t want to have this very material practice. Then moving to Amsterdam, I had a studio space and I didn’t know what to do with it. I just sat there. The work I was making had to do with how to bridge this difference between how history is taught and how it is represented. But I was also interested in the legacy of conceptual art, the preoccupation with language, and whether art is a form of communication. Is it a language? Is there such a thing as a visual language? I was trying to look for images that operated as words, or something that could be deciphered or understood in an image. But moving to the Netherlands meant that I realised I had been working with images that dealt with Argentinian history, not European history. Suddenly, I became an Argentinian artist, when I moved away.

Moving and taking that opportunity of the Rijksakademie generated a crisis in the work. It was a crisis at that time that was very expected from artists – this sense of site specificity. I decided to make work about that difficulty. I first made a work, for the Rijksakademie open studios, called Oranje. I opened the studio, kept the door ajar at 45 degrees. Then I painted everything in the studio that you could see from the outside orange, that special Dutch colour of orange, the national colour. But when you came in, everything that was not in that line of sight was not painted. Everything else had its own colour and texture.

VS: Then you moved to work with more universally significant objects – such as bunting or chairs?

AP: The bunting was about trying to look at signifiers of shared common space as a happy moment, and how there are these signals that tell us we can be happy with these strangers even though we don’t know them and we don’t love them. And that can be a metaphor for how we share social space. It’s both a search for universality but also embracing misunderstandings or lacking the code. And maybe that’s a better metaphor for what looking at an artwork really is. You bring your own stuff. You don’t just get to read what the artist wants you to know: it’s somewhere in between those two, both searching for universal gestures and also searching for that failure. What becomes important is that we’re still trying to talk to each other, even though we might not share a code.

VS: Tell me about the bunting performance you presented at the Venice Biennale in 2011.

AP: The performance is called Strangers. Two people who never met before are hired to just hold this bunting. On the one hand, they have this sense of decorating the space, like you would for a birthday party, but you’re decorating an art space. I think of it as a sculpture rather than a performance. They’re not moving, but they’re not entirely still. They are connected by this line, but they can’t be close to each other. To me, that work is almost like a sculptural representation of cultural intimacy. What are these signifiers that connect you with other people, that keep you at a distance but bring you together? Cultural intimacy is that kind of social glue that I was looking for.

VS: It is fascinating that you mention that experience with your grandma as a theatre director. I can see how that might influence what you do: theatre provides a visual and narrative framework for examining social dynamics playing out in certain ways, both artificial and spontaneous.

AP: She was the only artistic person in the family and she’s the only person in my family who freaked out when I said I wanted to study art (laughter). She was a fascinating character – on one hand, very liberal and interesting, but she had this conservative streak. She told me: “The only reason I was able to be a theatre director was because I married a doctor.”

VS: Yet here you are, with a really strong, established practice, represented by a major New York gallery. How does one go from there – taking that leap of faith with the Rijksakademie – to here?

AP: I think it took me a really long time to call myself an artist. It’s such a weird thing to call yourself, because for a long time I wasn’t sure I deserved to call myself an artist. But then I thought this is what I do. I just kept doing it.

VS: Were you applying for competitions, residencies?

AP: The thing that was incredibly difficult was that, for many years, I had an Argentinian passport. Now I have a British passport. But when I was in the Netherlands, in order to stay there, I could only be an artist. There was no other way I could make a living. I could only make money as an artist. The Rijksakademie gives you a stipend, so for two years I was sorted. Then I sold some drawings at the Open Studios, which meant I could manage for a few months. Even though I was not eligible for any grants, with no European passport, there is more of a culture of getting artists who are not public space artists to do public works, which I still do and enjoy. That’s a different pot of money. I am commercially represented and I sell some work, but not all my work is possible to sell, so I don’t exclusively make a living from sales. It’s this combination of fees, sometimes I’m teaching, sometimes sales come together.

VS: For commissions, do you still apply or do people come to you now?

AP: People come to me more. I do apply sometimes, but not very often. I often get asked to apply. But I’ll not always get chosen. I’m still exploring what it means to be mid-career. It’s a different kind of difficulty. You’re not like the hot, up-and-coming artist. Obviously, I still sometimes remember my grandmother. Now I have a kid and have to maintain a household. Maybe I should have listened to her (laughs). But I feel incredibly lucky to have got to do this with no other job, for so many years. I came here at 24 and I’m 46 now.

VS: Bureaucratic obstacles have been deployed to great effect in one or two of your works. Can you tell me about the Joy in Paperwork series?

AP: I tried to become British as soon as I had been here for long enough, but the problem was that I was getting a lot of invitations to do residencies and I travelled a lot. The year that I applied for citizenship, I had been away for 235 days in a year, so my application was rejected because I hadn’t spent enough time here. They didn’t understand the travel.

VS: They didn’t know that if you’re away so much as an artist, it’s because you’re doing well!

AP: Yes, exactly. The lawyer said the Home Office doesn’t like people to appeal, so wait a year, then reapply. I was saving to buy a flat. She said try to buy a property and try to stay put. So, I stayed home for a year. My passport stamps had caused the problems, so that’s when I asked people to send me their stamps. [This resulted in Joy in Paperwork, The Archive (2016) shown at the New Art Gallery, Walsall, comprising a gallery filled floor to ceiling with envelopes containing official stamps from all over the world].

Amalia Pica, Bureaucratic Obstacle, Installation view, Museo Jumex, Mexico City, MX, 2023. © Amalia Pica. Courtesy of the artist; Herald St, London; and Museo Jumex, Mexico City. Photo: Ramiro Chaves.

Then I did this other work, called the Bureaucratic Obstacle. This was at the Jumex Museum [in Mexico City in 2023]. I built a very simple labyrinth out of office partition walls – the ones that are covered in fabric and slotted together. The museum guards become the guardians of the labyrinth. At the entrance, you have a guard who gives you a form to fill in. The form is really absurd. It says things like: “Please tick one of these boxes and there are 25 boxes that you could tick. And then the guard could pick on you and make you fill out two or three forms. A queue would form, a line of people wanting to go in. As soon as your form was accepted and you were allowed entry to the labyrinth, they would just shred the form in front of you and it would fall into the labyrinth which was full of shredded paper. And the shredded paper was the dead archive of Jumex, the corporation. But then, inside the labyrinth, people used the shredded paper as confetti and were having paper fights. So, it became festive, joyful.

VS: Despite these obstacles, the work you made in response seems quite affectionate and ironic. Do you feel darker work is needed in darker times?

AP: I think there is something about joy and also beauty, or formal aspects of works, that I’ve always tried to (express). If you put your finger on a hot topic, people are not going to change their minds. I try to get there a little bit before, exploring things that are seemingly harmless but touch on aspects to do with community and conflict resolution.

• Amalia Pica: Keepsake is at Cample Line, Cample, Dumfriesshire, until 14 December 2025.