Nalini Malani, Studio Bombay. Photo: Johan Pijnappel. © Nalini Malani.

by JULIET RIX

The Indian artist Nalini Malani was born in 1946 in Karachi, then in British India, now in Pakistan, but she and her family were soon forced to move by partition. This experience of conflict, displacement and refuge has marked her life and work, which focuses on the oppressed and voiceless, especially women. Her family moved first to Kolkata, and then, in 1958, settled in Mumbai, which remains the artist’s home where she lives and works for most of the year.

.jpg)

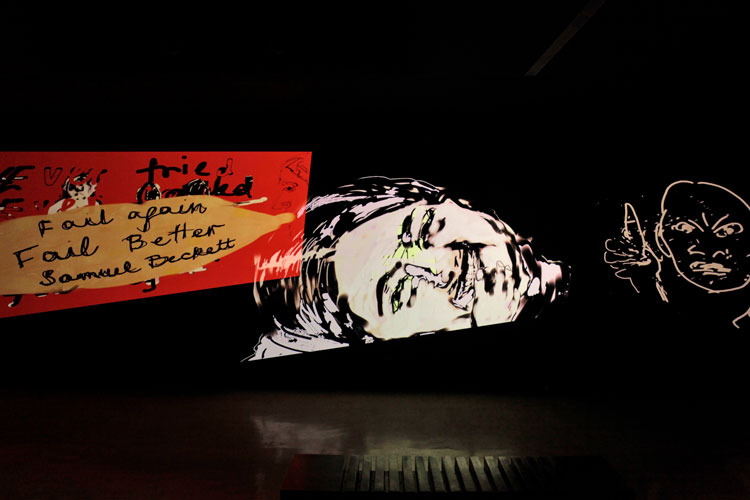

Nalini Malani, You Don’t Hear Me, installation view, Joan Miró museum, Barcelona, 2020. Photo: TanitPlana. © Nalini Malani.

During her study at the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art, Malani had a studio from 1964-68 at the Bhulabhai Memorial Institute, a multidisciplinary centre, where artists, musicians, dancers and theatre actors worked individually and as a community. After graduating in 1969, she became the youngest participant in the Vision Exchange Workshop (VIEW), which offered unusual facilities for India at the time and allowed her to make a series of photograms and 8mm and 16mm films.

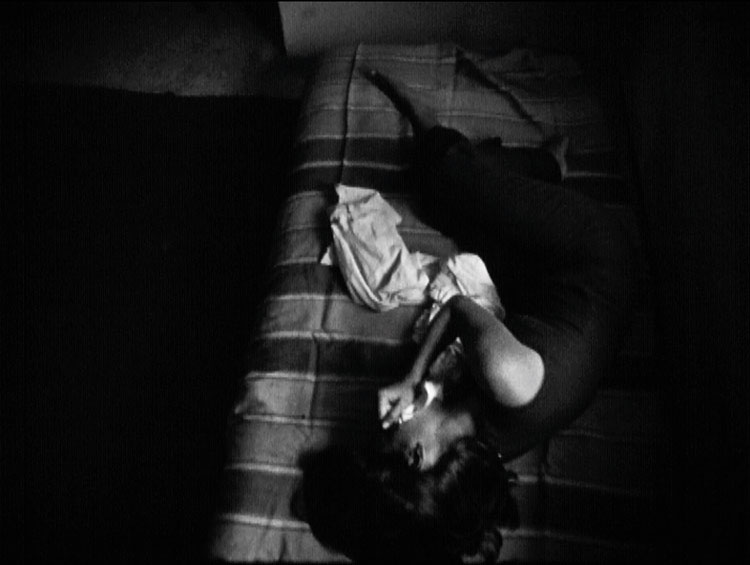

Nalini Malani, Onanism, 1969. Digitised 16mm black and white film, 3:52 min, silent. Collection: MoMA, New York. Photo: Nalini Malani. © Nalini Malani.

Awarded a scholarship by the French government, she lived in Paris from 1970-72, a period not long after the upheavals of 1968 that helped sharpen her political sensibilities. Returning to India, still in its infancy as a state, she moved to the heart of Mumbai’s bustling wholesale market, Lohar Chawl, where her work reflected the lives of middle-class Indian families as well as pavement dwellers.

In 1979, after meeting Nancy Spero, May Stevens and Ana Mendieta at the AIR Gallery in New York (the first all-female artists’ cooperative gallery in the US), Malani decided to organise an exhibition entirely of female artists in India. She was distressed by the lack of interest, and it took until 1986 for it to happen. Through the Looking Glass toured for three years to five non-commercial venues.

Nalini Malani, All We Imagine as Light, 2017. Eleven panel reverse painting on acrylic sheet, 183 x 1100 cm. Installation view: Nalini Malani: The Rebellion of the Dead-Part I, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2017. Collection: Burger Collection, Hong Kong. Photo: Ranabir Das. © Nalini Malani.

Malani has won several awards and served residencies across the globe, including in Singapore, Japan, the US and Italy. She has had 20 solo exhibitions in the last two decades, including a major retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in 2017 and the Castello di Rivoli in 2018.

She has just been awarded the first National Gallery Contemporary Fellowship (supported by the Art Fund). In collaboration with a regional collecting institution – this year the Holburne Museum, Bath – the new fellowship is a two-year research, production and exhibition programme allowing an artist of international renown to work closely with specialists from the two institutions and explore their collections to create new work for a final show.

The next three years will be busy, with solos shows coming up at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, Serralves Museum of Contemporary Art in Porto, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, and back in the UK, the fellowship final exhibition at the Holburne Museum in autumn 2022 and the National Gallery in spring 2023.

Last year, Malani won the 2019 Joan Miró Prize and just managed to get the resulting retrospective hung at the Joan Miró museum in Barcelona before lockdown. The exhibition, You Don’t Hear Me, finally opened last month.

Juliet Rix: Congratulations on the fellowship.

Nalini Malani: Thank you. It came as a big surprise, a wonderful surprise. I’m still processing it.

JR: It isn’t the ideal time for it, mid-pandemic. How will you do it?

NM: I am not able to come to London at the moment (though I will later). I’m 74 and very much in the vulnerable category, and I have two daughters watching over me like hawks, one in the US, one in Bombay [Mumbai]. To be able to start, the curators have sent me two tomes of the National Gallery collection, a massive amount of digital files and links. And I have almost weekly online meetings with the team of the National Gallery and the Holburne museum.

For me, an artwork is made in three steps (to adapt a quote from Walter Benjamin) – a musical stage when it is composed, an architectonic one when it is built and a textile one when it is woven. I am at the moment going through the musical stage when I am collecting things and putting them together. This musical stage could easily take till the end of this year.

A few ideas are popping up in my head. There have been some excellent X-rays made of National Gallery paintings showing earlier pictures underneath the ones that we actually see. They’re fascinating. One portrait of a woman has beneath it a bearded old man. Why was the man annihilated? It could have been practical – the artist had no funds for more art materials – but we can spin lots of interesting narratives.

Nalini Malani, Sita I, 2006. Acrylic and enamel reverse painting on Mylar sheet, 183 x 122 cm. Courtesy and copyright Nalini Malani.

The retelling of stories, from a different angle, and a different often feminist purpose, has been at the core of my art for decades. I work a lot with text and I’m absolutely fascinated with narratives and fictions from different cultures and periods, which I believe belong to all of us.

A major turning point in my relationship to written sources in my work came in 1979 when I met the artist RB Kitaj at one of his exhibitions in New York. There I saw an artwork titled If Not, Not, taken from TS Eliot’s The Wasteland. Kitaj said to me: “Some texts have artworks in them.” Since then, the inclusion of literary or philosophical excerpts has remained a constant in my practice.

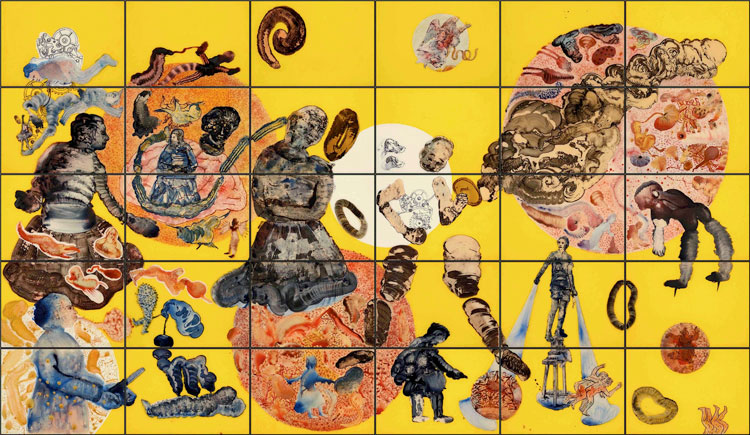

JR: You work with myth quite a lot – Cassandra, Medea, Sita. What draws you to them?

NM: There are similarities in the Greek and Indian myths. People have forgotten, especially in the west, that Alexander’s army came up to Afghanistan and a little beyond. Alexander went back to Persia, but the army stayed behind and we have an Indo-Hellenic school of sculpture that is very much part of our Indian tradition. The Greek myths don’t belong only to the west. Sita and Medea have a lot of commonality, and there is a character called Sahdev in the Mahabharata who is quite like Cassandra. I use myth because the artist’s endeavour is always to connect with the people who come to see one’s work and mythologies are link languages. They have come to us like universal truths, without authors. What I want to do is bring them into the contemporary arena.

Nalini Malani, Cassandra, 2009. Thirty panel reverse painting on acrylic sheet, overall size 228 x 396 cm. Collection: Kiran Nadar Museum of Art, New Delhi. Photo: Anil Rane. © Nalini Malani.

For me, Cassandra is female thought – the instinctive thought that is the domain of the female. Feminine, masculine and abstract ideas exist in all humans and it’s up to us to respect them all and let them come together in a creative, humanistic way. We must not denigrate the feminine. At the moment, masculinity has taken over in a huge, almost pandemic, way, especially in the characters we have in the US and, I’m afraid, in the UK. I was reading recently that certain states in the US are trying to ban abortion. How far backwards are we going? It’s almost as if this is a psychic war. The male idea against the female idea, and for men like Donald Trump, [Turkish president Recep Tayyip] Erdoğan and [Brazilian president Jair] Bolsonaro, the denigration of the feminine has to be complete. They don’t even deserve the word patriarchal. Theirs is malevolent masculinity.

The future is female. There is no other way. We have to work with that idea, otherwise we’re doomed.

The kind of capitalism we’re experiencing has no concern for the Earth or the environment. It’s as if nature is infinite, but it’s not. In Bombay and Delhi, the pollution is awful, but in the last few months of this pandemic, the air has become as pure as in the Swiss Alps. It shows that, with a few months of vacation from the human being, the Earth bounces back. And Bombay’s marshy area, where fewer and fewer flamingos have come over the past years, is now totally full of pink flamingos!

This is Cassandra. It is right in front of us. Cassandra refused Apollo’s sexual advances and he cursed her; she could “see” the future but no one would believe her. Her father locked her up and accepted the Greek’s gift of the wooden horse – and that was the end of Troy. She knew what would happen. We know, too, and we need to act. We must speak up. That’s where art comes in.

JR: Is it the role of art to get people talking about these things?

NM: There are many roles that art plays – this is one of them. Journalists do it, of course, but the way art does it, it comes in an unconscious way where the ideas creep into the viewer by themselves. I believe that it’s a three-bodied relationship between the artist, the art object and the viewer. The three together wake up the art; otherwise it lies dormant. With this three-bodied conversation, much can happen.

-.jpg)

Nalini Malani, In Search of Vanished Blood, 2012. Six channel video/shadow play with five reverse painted Mylar cylinders, sound, 11 minutes. Installation view: Nalini Malani: In Search of Vanished Blood, ICA Boston, 2015. Collection: Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. Photo: Danita Jo. © Nalini Malani.

JR: Where have you been in lockdown?

NM: I am in Amsterdam. My husband is Dutch. We live in Bombay, but we have a small flat and a small studio here. We were in Barcelona setting up my show from 1 to 13 March. By the 13th, the virus was spreading like crazy in Spain and we got the last flight out to Amsterdam. The show couldn’t open. Barcelona locked down. It opened on 18 June with distanced visitors. We did a virtual press conference and walk-through.

We were supposed to fly back to India on 25 March, but India went into lockdown and my daughter in Bombay said: “Don’t you dare come, the quarantine facilities are terrible and you’ll get sick in quarantine.” So, I changed my ticket and they’ve extended my visa in Europe.

I was fully isolated for 100 days after we arrived in Amsterdam, I didn’t leave the flat. Stepping outside a few days ago was like being in a magical world – just amazing. Every flower, every blossom, the Linden trees in bloom – the fragrance was absolutely fantastic. It was devastatingly magical.

JR: Are you working on any art about the virus or relating to it?

NM: For me, it takes time. The thoughts come and go, but to actually find a picturisation takes time. At the moment it’s only in my animations – which I post on Instagram (@nalinimalani). These are my animated notebooks. Whenever something irritates, excites or interests me, I make an animation about it.

At the Whitechapel, I will be showing an Animation Chamber, as the annual commission for its library. I first showed this at the Goethe-Institut in Bombay for its 50th anniversary last year and I will bring 56 animations from there, many inspired by certain books that travel everywhere with me – books by Hannah Arendt, French philosopher Simone Weil, and Indian anthropologist and sociologist Veena Das.

Nalini Malani, Can You Hear Me?, 2019. Animation Chamber, 11 channel installation with 56 single channel stop motion animations, sound. Installation view: Can You Hear Me?, Goethe Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan Mumbai, 2019. Photo: Ranabir Das. © Nalini Malani.

At the Whitechapel, there will be something like 84 animations with the new ones specific to the Whitechapel, inspired by its history and the East End area around it. That’s what I’m working on now, so this is where you might see a hint at what we are facing now worldwide with the pandemic.

The Animation Chamber will be a very immersive environment with projections directly on to the brick walls. It will be like walking into an accordion book. There are quotes – mostly text, but in one case audio of Samuel Beckett’s Endgame – and I composed the music as well. It is like moving graffiti with sound.

The lockdown directly influences the preparation for the Whitechapel Gallery show, which opens in September. We are working on it by Skype and Zoom, with online planning and installing. I have quite some experience with this, as I started working more virtually in around 2011 to cut down on my carbon footprint.

JR: Are you able to do anything to make the Whitechapel work safer to visit from a coronavirus point of view?

NM: Yes. My husband is brilliant at planning space and he’s been working with the two technical people at the Whitechapel. We’ve demarcated positions where people can stand and walk, and there will be no more than 15 people in the room, with six feet between them. The choreography is in place, people just have to follow it.

Nalini Malani, Utopia, 1969-1976. Two channel film installation, digitized 16 mm b/w and 8 mm colour, 4:39 min, silent. Collection: Centre Pompidou, Paris. Photo: Nalini Malani. © Nalini Malani.

JR: How did you start working with moving images and multimedia?

NM: I started early using film. I made five or six films in 1969 when I finished art school. I was fortunate to have access to equipment for lens-based work at VIEW (Vision Exchange Workshop). I made prints and films. There was also a darkroom, but I didn’t own a camera so I made a series of large-format photograms.

I made my first animation film in 1969. It was a time when India was going through a modernist phase and India’s first prime minister, Nehru, commissioned Le Corbusier to design the city of Chandigarh. The first Nehru lecture was given by Buckminster Fuller. I met him and had dinner with him, quite something for a 23-year-old. So, I made myself a model town, like an architect’s maquette, and shot this with coloured filters. I called it Dream Houses because it was based on an idealised township for the labouring class, largely workers from rural India coming in droves into the city to find work. The architect Charles Correa – originally from Goa - designed a township for New Bombay where each cottage had a small piece of land to cultivate so the people could continue to do what they were used to. It was a brilliant idea but, of course, politicians shot it down and avaricious builders came in.

Dream Houses is now showing in Barcelona at the Miró museum – an exhibition of my works from 1969-2018 – along with the sequel I made in 1976. By then, the dream had come to nought so I made a black-and-white film where a young woman looks out at a shanty town, seeing that no more can it be her dream to own a dream house, and parts of the 1969 film are superimposed on her face. I show the two pieces as a film diptych.

JR: How do you decide which medium to use for a given work or subject?

NM: Each subject is larger than one artwork. Like Cassandra; that has been going for two decades. Medea as well. It can’t be contained in one material or one work. So I start small, with a book perhaps, then it may become a painting, a reverse painting on glass (not a very classical medium, more a folk medium – I love it), then it might turn into a video shadow play that is more immersive, more theatrical.

Nalini Malani, Gamepieces, 2003. Four channel video/shadow play, with six reverse painted Lexan cylinders, sound, 7 minutes. Installation view: Scenes from a New Heritage, MoMA, New York, 2015. Collection: MoMA, New York. Photo: Johan Pijnappel. © Nalini Malani

The new format I’m using now is the animations. To make them, I just need my iPad and my fingers. I don’t even use the iPad pencil. I can do it anywhere: I can be sitting in the park and I can still make an animation. That’s very important for me now, during this time of self-isolation, I can still make art in my iPad studio. And I can compose on it as well. By placing them on Instagram, I can still be in contact with my audience, even when the museums are closed.

JR: You organised the first exhibition of female artists in India in 1985. Are you pleased with how many female artists are now working and getting recognition?

NM: Yes, this is wonderful. In this extremely macho decade, more than ever our female voices need to be heard. Within the art scene, this decade has been like a sense of redemption. Many of the older women – such as Phyllida Barlow – who were totally unknown are finally having big exhibitions and getting the recognition due to them. I hope it is not just a fashion, but goes deep into society. This is very important.

JR: Who are your favourite contemporary artists and influences?

NM: There is one artist we all love, who is no more but whose life gave us so much – Louise Bourgeois. We had a plan to collaborate, but it never crystallised as she suddenly passed away soon after we met. I have dear international artist friends I really admire, such as Kiki Smith, Fiona Hall and Kimsooja. And, in India, Arpita Singh and Nilima Sheikh. All doing super work. As for visual artists who influence me, I would also count Hieronymus Bosch, Rembrandt and Goya. Although they passed away a long time ago, I feel that what they have to say through their art is still contemporary and, for me, they are therefore contemporary artists.

.jpg)

Nalini Malani, Remembering Mad Meg, 2007. Four channel video/shadow play, with eight reverse painted Lexan Cylinders, each 122 x 122 cm. Installation view: Paris-New Delhi-Bombay, Centre Pompidou, 2011. Collection: Centre Pompidou, 2011. Photo: Payal Kapadia. © Nalini Malani.

JR: Are you still working with the character of Mad Meg (from Bruegel’s Dulle Griet), whom you have used in past work?

NM: Yes. I carry the image with me on my iPad. It’s an amazing painting. I don’t know what the artist’s intention was, but this woman has a saucepan on her head and all these pans attached to her belt and this army of creatures trying to cleanse the land. I did a whole shadow play around her for my solo show at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, which is in a former military hospital. Walking through the long corridor, I felt one could still “hear” the screaming soldiers with their war-torn traumatic minds. To prepare myself for this work, I travelled to Antwerp to see the original at the Museum Mayer van den Bergh. This painting is so amazing that you want to pull up a chair and spend the next 24 hours in front of it. Something of that captivating spirit I wanted to give in my work Remembering Mad Meg, as a four-channel video/shadow play with eight reverse-painted cylinders. In Breugel’s time, many such women were burnt as witches, but here she is, sort of liberated, striding across the land. I find Mad Meg fascinating and will make more work on her. She’s not going to leave me for a long time.

JR: What does she represent for you?

NM: Breugel has made her a huge figure and everyone else is quite small. There is a feeling of power, but not in a negative way. There is something she is outraged about and I identify with that in certain cases, especially the epidemic of rape we now have in India. And it’s not only rape of grownup woman, but girls as young as three years old.

The worst one was two years ago when an eight-year-old from a nomadic tribe in Kashmir, who took her ponies into the forest to graze, was caught by eight men, shoved inside a temple, fed on drugs for eight days, raped, and finally strangled. But the most obnoxious, atrocious part is that the seventh man called the eighth man on the phone and said she was dying and the eighth man said: “Keep her alive until I arrive.” What can you say to this?

Even an eight-year-old is seen as “other” just because she is Muslim. These things are videoed and put online. And so often the men are not punished. This is where Veena Das comes in. She writes that our nationalism, jingoism, is written on the bodies of women. They are so vulnerable – especially girl children.

I did an homage to that eight-year-old girl, Asifa Bano, last year. This crime cannot be forgotten. When the Goethe-Institut in Bombay invited me to do its anniversary show, it also wanted to do a public event so we chose a very iconic venue at the Gateway of India, the famous Taj hotel, which has a modern, almost 80-metre, tower. It has a slab of concrete with no windows and on that I did a 60-metre-high animation specially for this girl, which attracted thousands and thousands of people. The Taj is the tallest building in the area, so even on the cricket grounds far away you could see it.

Nalini Malani, Can You Hear Me?, 2019. City Specific Video Mapping, 57 single channel stop motion animations, sound animations, sound. Installation view: Can You Hear Me?, TAJ Hotel, February, Mumbai 2020. Photo: Ranabir Das. © Nalini Malani.

JR: How do you feel about the future? Optimistic? Pessimistic?

NM: Neither. You can get to the bottom of the pit and then realise there is light above. Let’s crawl out of that pit and do something about it. Without hope, there’s no life. You have to hope.

We have reached a threshold in this pandemic and when we cross that threshold (when there is a vaccine and treatments and we come out of this), we must not return to the way things were before. That would be a tragedy. This is a lesson.

JR: And where does art go from here?

NM: The funny thing is that for the last three months, artists have been exchanging notes saying everybody is looking at art on social media, while they are sitting at home. Not only visual arts, but music and literature. There are so many podcasts, audio novels and music online – more than ever, people are looking at art. That is what’s keeping them going. Art is like oxygen, like fresh air.

Boredom is the interface of art, and boredom leads to violence. That needs to be examined: how the mind that is capable of such vastness can become so narrow that it gets fed up of itself and goes out on a destructive spree because there’s this need to have some kind of adventure, to fill that void of boredom. Art can do a lot to fill that void and open the imagination.

We need to have more art at school level – not just going to museums to look at art, but making things.

JR: Do you go into schools to work with children?

NM: I used to, in India, and during some residencies including in Japan, and I really enjoyed it. I send my animations out on Instagram so children of all ages everywhere can access them. But now I’m 74 and don’t have so much time on Earth, I feel I want to make a few things before I pass on.

• Nalini Malani: You Don’t Hear Me is at Fundació Joan Miró, Barcelona, until 20 November 2020.