Maurice Burns in his studio. Photo © the artist.

by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

A small, but refreshingly lively exhibition of paintings by Maurice Burns, an 83-year old artist from Santa Fe, New Mexico, reminds us that painting can be an enjoyable and relaxing occupation, as much as one can enjoy oneself and relax while working out an intense personal experience. Burns, who was born in 1937 in Talladega, Alabama, into a family with mixed Scottish, Irish, Indian, Jewish and black origins, has seen it all: growing up in a segregated community; persevering in getting to study at Purdue University as one of very few students of colour accepted there at the time; serving in the army; entering the workforce with an engineering degree … Throughout these life stages of making practical decisions about earning his living, Burns maintained a strong interest in drawing and making art, which he pursued from an early age. Then, in his early 30s, he decided to switch careers and become a professional artist.

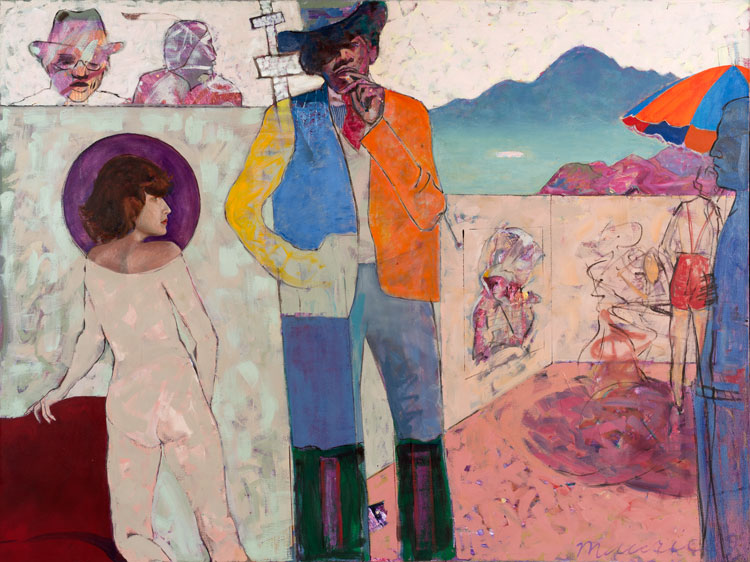

Maurice Burns. Notes to Myself, 1989-93. Oil on canvas, 56 x 68 x 1 1/2 in. Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

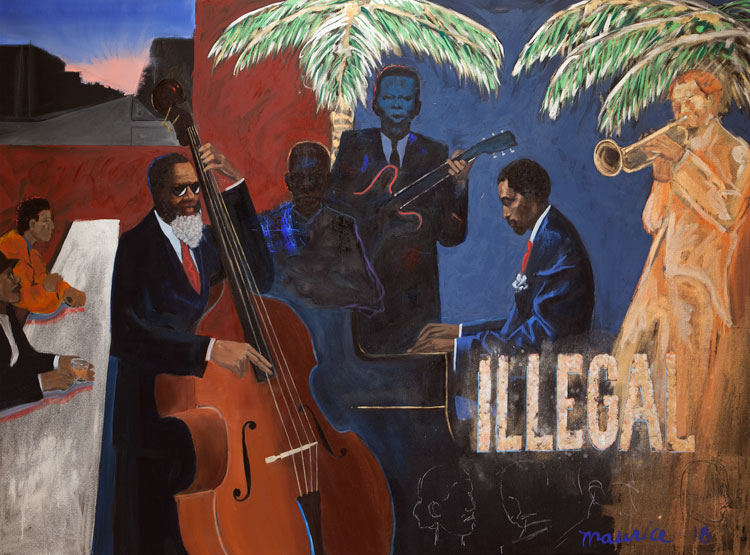

Burns’ paintings are vivid and sincere, alive with a kind of energy that only painting can bring to its surface. His composition is usually complex, collage-like, with overlapping layers of narratives and meanings. Notes to Myself (1989-1993), for instance, features two couples in the foreground of the painting: two women – one black, one white – talk in a friendly manner while a dressed-up pair embrace under a palm tree. The two couples seem to have little to do with each other, brought together by a composition with a red background, reminiscent of Matisse’s Red Room in its all-over quality, opening up on to a scene with a lonely man standing at a bar. We see a portrait of a man with Indian headgear on a wall, an opening into a darker space on the side with a hanging image of a sun-drenched city. Like a scene from a dream, this painting brings to mind associations with spaces inside ourselves that may be open or closed, shared with other people or kept to ourselves. Whereas Burns’ earlier works appear to deal more with his personal experiences, his latest series is dedicated to black musicians: Thelonious Monk (1917-1982), Junior Wells (1934-1998), Miles Davis (1926-1991), Jimmy Yancey (1894-1951) and Birdman (b1969). True to Burns’ style, these paintings often have overlapping, collage-like compositional layers with a clearer theme associated with the name of a particular musician. In Birdman Plays the Blues (2019), for instance, the main protagonist is in the foreground, playing saxophone, with his band and the piano player to the left. Birdman’s saxophone throws a greenish shadow on his bright-white shirt, which contrasts sharply with a dark purple background and the dark blue suit of a piano player next to him. The overall effect is that of spontaneity, expressive use of colour, and a desire to capture a moment saturated by live sound and the emotion it evokes. Studio International spoke to Burns on the occasion of his first solo show in New York, at Gerald Peters Gallery.

Maurice Burns. Birdman Plays the Blues, 2019. Oil on canvas, 56 x 76 x 1 1/2 in. Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

Natasha Kurchanova: Thank you for speaking to Studio International, Mr Burns, and congratulations on your first show in New York. It looks beautiful. I could not find much information about you, except a book by Elton Fax, Black Artists of the New Generation, which was published in 1977. Among the things I learned was that you were born into a family of mixed heritage in Alabama. In your life, you made some courageous and principled decisions, which determined its course in many ways. One of these decisions was to change from a successful career in the burgeoning computer industry in the early 1960s to the uncertain path of an artist. Could you say a little more about how you decided to become an artist?

Maurice Burns: I made art since I was a kid. Back then, I did not think seriously about following through with it. My first trade was as a bricklayer; I learned it from my father. I was also good at math, so my first job was working as a telephone installer at Illinois Bell Telephone Company in Cary, Indiana. Then I went to computer school to learn programming and finally got a job designing systems at Chicago City College, which were implemented by my boss. It was then that I said to myself that I could do what I wanted, as my income was settled and I did not have to worry about money. So, I started drawing – I took an art class with Hilda Rubin at Carl Sandburg Village in Chicago. At that point, I had never drawn from a model before. The person conducting the art class noticed my skill in drawing so he encouraged me. But then, I received a promotion at my job, where I was designing systems: they wanted me to take over the whole department. It was the dawn of the computer age and everybody was switching over to computers. They wanted to promote me to the head of the computer department so that they could keep track of all their departments. I had studied advanced maths and could do the job. However, I had to go to college again to get a degree to be eligible for this position. I was in the service during the war, and by that time, I already had about three years of credits with the GI Bill, but not enough to get a degree. So, I wanted to get the full run out of the GI Bill. [Officially the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the GI Bill was created to help second world war veterans.]

Maurice Burns. Blues for Linda, 1989-93. Oil on canvas, 56 1/4 x 76 x 1 1/2 in. Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

I talked to people at IBM about a good way to learn computers, and was told that knowing music was one of them. This idea caught my attention, as I always associated music with art and creative process in general. This gave me the impulse to think about going to an art school to get my degree in art, and then come back and fill that position. I applied to different art schools and was accepted at almost all of them, which was a surprise, because I was around 30 then, and it was my last chance to get a degree.

When I was working in the computer industry, I was making a lot of money. Switching to an art career was a big decision. I was married; my wife was also working with computers. She did not like the idea of me studying art. She thought it was crazy. We had a falling out about it among other things. I came home from work one day, and found my apartment empty, because she had got a moving company to come and move everything out. I thought: “Well, at least I do not have to worry about moving out anything, and I do not have anything holding me in Chicago, now that she is gone.”

Maurice Burns. Galisteo Fantasy (diptych), 1989-93. Oil on canvas, 56 x 119 1/4 in overall. Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

I decided to follow through with my idea of becoming an artist. I went to Rhode Island School of Design because it was one of the top schools in the country. The first summer I was there, I also went to Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, where I met some very famous artists at the time – Brice Marden and Jacob Lawrence, among others. I was very much encouraged by the staff there to pursue my artistic career. After my last year at RISD, I was accepted at MacDowell Colony through a friend of mine who recommended me. I painted there for three months. After graduating from RISD, I applied to Yale University for graduate school. I was interviewed by Al Held, who taught at the art department at Yale at the time. He asked why I wanted to study at Yale. I told him I was not sure that I did, and that I wanted to hear from them what they had to offer. He said, as a graduate of Yale, I would have a better chance of getting a job teaching. He also said my work was good enough for me to go to New York and try to make it there as an artist. I thought that was not such a bad idea. I decided not to go to Yale, because at the time, it did not give scholarships to first-year graduate students, and they did not allow me to have my own studio off campus. Then – it was in 1972 – I had a great studio in Rhode Island, and I decided to go back there. Unfortunately, in a couple of months, a fire demolished that studio. At that time, I still had a couple of years left on my GI Bill, and Skowhegan notified me of an opportunity to study at the Royal College of Art in London. I could not pass up something like this, since I had already said no to Yale. I accepted the offer. It was arranged by Sir Robin Darwin (1910-1974), who was in charge of the Royal College at the time. I went there for a three-month stay. They liked me, and I stayed for the three-year programme. After two years, my GI Bill was running out, and I was not able to stay for another year. The staff reviewed my work and graduated me anyway.

When I was still in London, I received a job offer to teach in Santa Fe at the Institute of American Indian Arts, a major school of Indian art. So, I never thought of going back to working with computers, because I had this job waiting for me. When I returned from London, I went back to MacDowell Colony for three months, and then came to New Mexico to start my new job. Apart from this job opportunity, I was drawn to the Southwest because I was looking for a place where I could work on my art without much stress and distraction, the way it was at MacDowell Colony. There, I did not have to worry about taking care of my daily necessities, which allowed me to be much more efficient in making art. When I arrived in Santa Fe, I helped to establish a programme at the Institute of American Indian Arts in conjunction with RISD, that allowed Indian students to get college credits for their work after a two-year course of study. I also got a job teaching at the College of Santa Fe, now known as the Santa Fe University of Art and Design. I taught there between 1977 and 1981. When I first got to Santa Fe, I showed at the New Mexico Biennial at the New Mexico Museum of Fine Art. I submitted work to this biennial, and it was accepted. People noticed it; it received a lot of attention. It was an encouraging beginning in a new place, so I just stayed with it; I never went back to computers.

Maurice Burns. Illegal, 2018. Oil on canvas, 56 x 76 x 1 1/2 in. Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

I found the Southwest more relaxing than New York or Chicago. The population of the entire state is a little more than 2 million; there is a lot of wide-open space. The land is beautiful; the people are fascinating. There are three cultures coexisting here: Hispanics are a majority. This state used to belong to Mexico, so a lot of Mexican people live here. Also, there are nine pueblos [Native American communities] and maybe three Indian reservations, so there is a strong presence of Indian culture. And then, there are white people, but they are in a minority. It’s the first place I have lived in the United States where whites are not a majority. This place is so diverse that there is no dominant culture imposing its will on everybody else. It’s a place that respects diversity, and it is more accepting of cultural difference. Here, you are either Hispanic and Indian, or an Anglo. It’s the first place in the United States where I was thought of as an Anglo rather than black. As you may know from Elton Fax’s book, my heritage is mixed. On my father’s side, my grandfather was Scotch-Irish and my grandmother was a Choctaw Indian. On my mother’s side, my grandmother was part Jewish and my grandfather black.

When I came, it was still pretty wild. I had to work on horse ranches to make some extra money. In the 80s and 90s, I worked as a set painter in movies for 17 years on and off. At that time, I was learning to play the guitar and worked on my art between movie gigs. Working in movies could become a full-time job, as it was paid very well, but I quit as it was distracting me from painting. Then everything started falling in place. I found my new home a conducive place to work. I had the opportunity to take care of a ranch where I could use a barn for a studio. I was not making a lot of money, but I got a lot of attention – shows and opportunities to continue painting. In 1992, I received a Pollock-Krasner grant.

Maurice Burns. Jimmy Yancey (quadriptych), 2013. Oil on canvas, 30 x 30 x 1 1/2 in (each). Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

In terms of personal life, I married for a second time. My wife’s parents gave us money to buy a house. Instead, I bought land and built a house with my own hands. While I was building it, I was living in a camper trailer. I was using a partially built house on an adjacent property as a studio. It had a dirt floor and adobe walls. It had nice light from a skylight. My wife was pregnant then, but we did not know that she was expecting twins. After one baby came out, the afterbirth turned out to be another girl. I delivered the twins myself, because the doctor could not get there in time, since we were living out in the country where I was building the house. We already had a toddler girl by the time the twins were born, and shortly after that my wife left for close to a year to pursue her interests. So, I ended up with three girls on my hands, just when I was getting opportunities to show my art. I was invited to show my paintings in Alabama, but I did not have enough money even to ship the work out there, so I had to give up this opportunity.

NK: Your path from working with computers to becoming an artist sounds fascinating and full of adventure. I would like to ask you about your artwork. The exhibition at Gerald Peters Gallery includes very recent paintings, from the last few years, and then there are works from the 80s and 90s. The most recent paintings have to do with music and black musicians. Before that, you seem to be interested in taking up subjects that address what’s going on with you personally, with the world in which you live.

MB: Yes, recently I have been painting subjects related to music, and before that it was going more in the direction of free association, motivated by my experience. I hang out in cowboy bars and Indian bars. Some paintings were based on free association that came up rather randomly. For example, the work called Harlem in the exhibition could also be called New York. It is an assemblage, and it is composed out of pieces I put together by free association. The way I made it expresses how I approach painting as well. Sometimes, one incident, one thought, or one image can trigger a painting. And then, in association with that particular image, others would emerge, and I would put it in there without any preconceived theme. There were exceptions to that method – for instance, Galisteo Fantasy. That derived from experiences that I had here in New Mexico.

Maurice Burns. Monk's Mood (diptych), 2013-14. Oil on canvas, 60 x 96 in (overall). Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

In my work, I was influenced by RB Kitaj when I was studying at the Royal College of Arts in London. We became good friends, and he was very encouraging. When I moved back to the United States, we continued to write to each other. He once wrote to me: “There is nothing more important for an artist than a period of impunity.” This mindset supported my inclination to move to New Mexico. In 1994, he had a major retrospective touring the Tate Gallery, LA County Museum of Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I wrote to him then, because we had not seen each other in many years. In my letter, I said: “We should meet, because you never know, we could die any minute and never see each other again.” Little did I know that after his exhibition opened at the Tate, his wife, Sandra Fisher, died. Sandy was also a good friend; I knew her from our London days. For Kitaj, drawing was very important; he always emphasised it. The Royal College of Art provided me with a model, and Sandy would frequently join me in my drawing sessions with a model. What happened was that Kitaj’s exhibition at the Tate was heavily criticised; it received the worst reviews. Sandy became so distraught by these bad reviews that she had brain aneurysm and died. I knew nothing about it when I wrote to him that we could die any minute, while she died around the time Kitaj received my letter. He answered me; we decided to meet in Los Angeles, during the run of his show there. When I arrived, I came to his talk and a question-and-answer session with David Hockney. I walked into a theatre that was full. I could not find a seat, so I was standing on the side, looking for Sandy. Then, before the talk, the announcer said that it was very difficult for Mr Kitaj to be there, because his wife had just died. When he said this, tears started running down my face. Somebody gave me a seat. After the question-and-answer session was over, Kitaj came up to me, and we hugged. He asked: “When did you find out that Sandy had just died?” I said: “Just now; just before you went up on stage.” And we were standing there, hugging each other and crying in the aisle. That’s the end of the story with Kitaj.

Maurice Burns. Moonlight on the Plains (A Little Romance), 1993-95. Oil on canvas, 75 7/8 x 55 7/8 in. Image courtesy the artist and Gerald Peters Contemporary.

NK: Are there any other artists who influenced you apart from Kitaj?

MB: There is a painter in Scottsdale, Arizona, named James G Davis. He had an effect on me. He showed mostly in Germany. He is another figurative painter who works in a contemporary way; he is not a traditional painter. Romare Bearden also influenced me, because he painted black people. I painted my life, in which I met Indian people, black people, white people. I grew up in a mixed society after I left my family. From the time I started working with computers, my environment was no longer all-black; I began socialising more with white people.

NK: How do you work? Do you begin with a drawing, with preparatory sketches?

MB: I do a lot of drawing, a lot of sketching. Drawing is mark-making for me, like it was for Basquiat. It does not define a figure. I paint mostly with oil on canvas, and sometimes I use acrylic as underpaint. Some of my paintings derive from drawings. I also collected a lot of pictures. I have boxes filled with graph books of images I cut out and kept. These images attracted me for one reason or another. I do not know myself why I choose an image. Shifting through them, sometimes an image gets my attention. Also, recently I went to Cuba and took pictures of the people dancing. My latest painting was of the guy in the yellow shirt dancing on the streets of Havana. I took a lot of photographs, but for my paintings I do not copy a photograph. I usually just use one figure from it or a detail. I take details from many photographs and then I put them together and create my own environment. I compose an image using collage aesthetic, where things can be out of scale, big or little, where I can mix things up. I compose in a very formal way, observing the laws of ratios and proportions. I studied old masters and the ways they composed their paintings in a very organised and predetermined manner. I started using some of those systems myself, and I still do. Even though I employ all these compositional devices, they do not determine my creative process. Figures in my paintings are not frozen in their environment, they are free-floating, they form part of the composition. I love listening to music when I paint. My favourite musicians are Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane. I would like to paint in the same way as Thelonious Monk composed music. It is interesting that music and painting use the same words to describe the work: composition, scale, harmonies, rhythm, intensity. I started associating music with my painting, so there is a musical undertone to them, a certain flow. I think musically when I compose my painting and in the choice of colours I use. I think of colours in painting as of volume in music – it can be loud, quiet, subtle, jarring. I do not charge my painting with any particular meaning; I bring various images and elements together and let people who look at my painting bring their own meaning to it. No matter what you paint, people are going to bring their own meaning to it. This is an interesting thing about painting – there are always surprises and discoveries that await you in the process of making a work.

NK: Thank you very much for sharing your thoughts and ideas about your life and work.

• Maurice Burns is at Gerald Peters Gallery, New York, until 13 March 2020.