Marguerite Humeau. Photo: Florine Bonaventure.

by EMILY SPICER

Marguerite Humeau (b1986, Cholet, France) deals in the sorts of mysteries that would not trouble most minds. What would a mammoth have sounded like? Or Cleopatra? What if elephants had out-evolved humans? How did culture start, and could it have anything to do with ingesting animals’ brains that contain hallucinogenic substances? Some might call Humeau’s investigations a little madcap, but these investigations are developed with the input of a huge range of experts.

Marguerite Humeau. MIST, exhibition view, Clearing Brussels, 2019. Photo: Eden Krsmanovic. Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York/Brussels.

For her MA graduate project at the Royal College of Art, Humeau attempted to resurrect the calls of three prehistoric creatures. The resultant piece saw the vocal tracts of a mammoth, a species of “walking whale” and a type of gigantic pig remodelled and mounted on tall, spindly stands in keeping with her futuristic, design-based aesthetic. The final pieces were the product of a great deal of educated guesswork, as vocal tracts are formed of soft tissue and rarely show up in fossil records. But, so thorough was her research, that University College London asked if it could use her sound files for a conference on mammoth calls.

Humeau says it is vital that her works aren’t seen as fictions. “All the worlds I am creating are based on real facts; they are based on mysteries that I am trying to understand. I am extracting real things, and then expanding into ‘what if?’ scenarios,” she says. “It comes from prototyping worlds that are invisible or extinct, or parallel to ours. They might exist, but we don’t really know about them.”

Marguerite Humeau. Venus of Frasassi, A 10-year-old female human has ingested a rabbit's brain, exhibition view, Kunstverein in Hamburg Year, 2019. Portland limestone, a cappella voice, 320 mm (L) x 280 mm (W) x 862 mm (H). Photo: Julia Andréone. Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York/Brussels

In 2018, Humeau reconstructed the voice of Cleopatra with the help of linguists and an ancient Egyptian love song from the Ramesside period. The resulting audio formed part of her installation Echoes, exhibited in the Art Now Space at Tate Britain in 2018. Just days before I visit Humeau in her studio, I hear about a project with an eerily (and eerie) Humeau-esque idea in mind. Researchers at Royal Holloway, University of London, the University of York and Leeds Museum are working with an exceptionally well-preserved Egyptian mummy. The remains are that of a priest named Nesyamun, who died more than 3,000 years ago. The inscription on his sarcophagus expressly stated his desire to speak again in the afterlife, so scientists set about making this a possibility by scanning his remains and producing a 3D printout of his larynx. The only sound they can currently produce is a sort of flat bleat, but they are working on forming words and eventually sentences..

Was this just a coincidence, or life imitating art? I put the question to Humeau as we sit in front of a board of her intricate pen drawings depicting a variety of futuristic sea creatures. “It’s funny because a lot of friends sent it to me saying just that. But I was inspired by scientists who were designing talking robots, so it’s not my idea. I think it’s just a coincidence, but it’s funny.”

Humeau is used to seeking out the advice of experts, such as anthropologists, biologists and palaeontologists. But how do scientists respond when she puts forward her proposals? Reactions are mixed, she tells me, but now that she has a catalogue of exhibitions behind her, her motives are easier to demonstrate. “A lot of people are quite open, and some are highly supportive,” she says. “Others are cynical, so it really varies. But now I have a history, a portfolio, people understand what I’m expecting from them, that I’m not a scientist, and I’m not trying to do something impossible in the scientific field.”

Marguerite Humeau. Echo, A matriarch engineered to die, 2016. Exhibition view, Palais de Tokyo, Paris. Polystyrene, white paint, acrylic parts, latex, silicone, nylon, glass artificial heart, water pxumps, water, potassium chloride, powder-coated metal stand, sound, W 120.2 x L 449.6 x H 136.1 cm (including stand) + Glass Heart W 30 x L 60 x H 30 cm. Photo: Spassky Fischer, Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New.

Humeau’s work is not just about trying to reconstruct something of the past, but also concerns excavating the future, as she puts it. For her project FOXP2 (named after the genetic marker responsible for speech), she created futuristic elephantine forms, imagining them as the dominant species on Earth. These four-legged overlords (which have been exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo and Nottingham Contemporary) were placed on carpets dyed with a concoction that Humeau describes as “liquid human”, mixed from the key chemical elements that make up our bodies. The result, surprisingly, was a very pleasant pink colour.

Humeau’s speculative worlds often see humans eradicated or subsumed by another species. These scenarios seem to reflect a largely unspoken bottom line, a creeping, collective angst bound to current affairs and the recent revelation that we, as humans, have now created an environmental epoch that could ultimately lead to our demise. I ask Humeau how far she is influenced by the notion of the Anthropocene, climate change and the possibility of human extinction – that ultimate elephant in the room. “I think we are becoming more and more conscious that we are just a dot on the timeline of the universe,” she says. “We are almost like a blast of air. My work is very much about that.”

Humeau explores these ideas in a typically imaginative way. She posits that mass extinction is making animals aware of their own mortality. It’s difficult to believe that animals don’t mourn, given what we know about our own pets, not to mention the distress displayed by whales, primates and elephants on nature documentaries when one of their number dies. But Humeau argues that animals also display ritualistic behaviour, and this, her research suggests, is on the increase. Could we, she asks, be witnessing a spiritual awakening in the animal kingdom?

Marguerite Humeau. The Dancers III & IV, Two marine mammals invoking higher spirits, 2019. Polystyrene, polyurethane resin, fibreglass, steel skeleton, pollution particles. Photo: Julia Andréone. Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York/Brussels.

For her show High Tide, which was most recently exhibited at the Centre Pompidou, Humeau sculptured a collection of futuristic marine mammals and set about imagining what they might sound like if they could recount complex narratives. With mechanical clicks and whistles, similar to those made by whales and dolphins, Humeau’s creations tell of a great flood – an apocalyptic deluge that sparked the birth of their culture. “These floods”, she explains, “might be the consequence of climate change and rising oceans and the air becoming toxic. Maybe the great flood is actually us. As humans, we are the flood.”

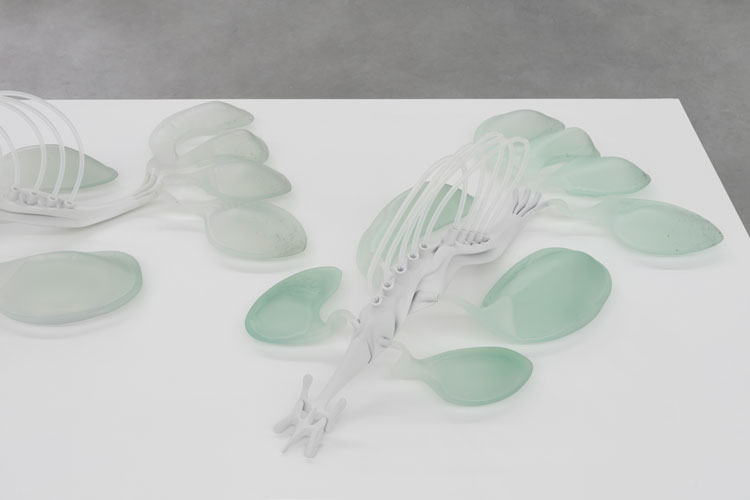

The marine creatures Humeau crafts are beautiful, but while these inventions are pastel-coloured and alluring, they are tinged with foreboding. “There’s always some kind of horrific twist, be it artificial skin, or the fact that some of the models appear to be breathing. I’m doing that intentionally to create a kind of sublime experience, a feeling of being exhilarated and frightened at the same time.”

Marguerite Humeau. The Dancer I, A marine mammal invoking higher spirits, 2019. Polystyrene, polyurethane resin, fibreglass, steel skeleton, pollution particles. Photo: Julia Andréone. Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York/Brussels.

The creatures Humeau made for High Tide looked more like abstract forms than animals we might recognise. They seem to be missing eyes and mouths, even heads. In some cases they were presented simply as a collection of respiratory organs, which Humeau imagines to be slowing mutating into plastic waste. This tale is a tragic one. Just as animals become like us in their thinking, just as they become more aware, their suffering increases.

“People tell me my work uses a language that belongs culturally to our idea of the future,” Humeau says of her strange creations. “But at the same time, they get very primal feelings through the sounds and the forms, which have been used since prehistoric times.” This is certainly the case for her Ecstasies series, which took inspiration from ancient Venus figurines. These are small Palaeolithic statuettes depicting women with large bellies and pendulous breasts, varying from the naturalist to the highly abstract. “I think there are forms that belong almost to our DNA,” she continues. “They’ve been transmitted from generation to generation.”

Ecstasies began when Humeau read an article by an American anthropologist who posits a link between the figurines and animal brains, which, she believes, early Europeans ingested in order to induce trance-like states. Humeau’s research has led her to believe that these states of altered consciousness may have been the root of art, religion and even language. “As soon as you start having those visions, the first thing you want to do is share them with the group. This random event could have triggered all the human wonders that we know.” With this in mind, Humeau modelled her own Venus sculptures, inspired by an amalgam of existing statuettes and images of animal brains. These were exhibited with recordings of “real human voices pushed to their limits”, designed to produce a kind of “trance room”.

Marguerite Humeau. MIST, exhibition view, Clearing Brussels, 2019. Photo: Eden Krsmanovic. Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York/Brussels.

Does Humeau consider how her sculptures will be viewed thousands of years from now? “Not really,” she says, “but I do think about the role of art in the future, and whether I could move towards this. I have been wondering about where it should be shown and experienced and I’m doing more outdoors projects. I think it’s very exciting to think about art that maybe doesn’t look like art, or art that is experienced by people randomly on their way to work. It should be part of our daily lives.”

Humeau also considers what environmentally sustainable art might look like in the future. “I think art was born from a will to become eternal, to leave a permanent trace, to transcend our human condition. Ever since we started to be conscious of our own mortality, I think we’ve been trying to transcend it.” The problem with this, she explains, is that we are making too much stuff. “I think artists are concerned about this, and as a species we have to consider the very idea of what art is about. For example, Tino Sehgal creates performances that are completely ephemeral, using human interactions as artworks. Maybe that is an interesting trajectory and I wonder whether it is the only one. I’m being very honest here. I don’t have all the answers.”

Humeau is keen to make the point that the digital realm is no less problematic when it comes to the environment. “I know that it might feel like we’re moving towards more and more immateriality, with the internet, for example, but for the cloud to happen, you need huge warehouses. And mobile phones are using rare Earth metals that come from mines, which are the toughest places to work in the world and are usually highly polluting as well.”

Marguerite Humeau. High Tide. Black ink pen on layout paper, 91 x 184 cm. Exhibition view, Clearing Brussels Year, 2019. Photo: Eden Krsmanovic. Courtesy the artist, CLEARING New York/Brussels.

Before long, we return to the question of mortality. “I’m obsessed with death,” she admits. “I think all of my work comes back to what life is about and what death is about and how new technologies have changed the relationship we have to it. New ways of being that have emerged. For example, algorithms on the internet are like the living dead. They give the impression that they are thinking, but at the same time they don’t have a soul, they don’t have a body. And Siri is this voice on our phones, and it feels like it’s alive and somehow it is, but not quite.”

In a way, Humeau’s sculptures are formed from a similar principle. These are creatures that you might imagine moving when your back is turned. Many of them have liquids pumped through them, and the accompanying voices, human or otherwise, give the impression of something coming alive and dying at the same time, heightening the sense of horror.

For this reason, Humeau is, arguably, the Dr Frankenstein of speculative art, and, just as this occurs to me, she shows me a slab of what looks like whale blubber, made from resin. “More recently, I’ve been developing these kinds of skins,” she says, “and introducing colour. This type of material is what I used for my show Mist in Brussels, and then High Tide at the Centre Pompidou. The material itself is bringing them to life or making them live on the edge of life and death. And I’m excited by that.”

I ask Humeau what she has lined up for her next project and she shows me a corner of her studio where the wall is peppered with images of cadavers. Some of these photographs are taken from the news; others show ancient remains pulled from the peat bogs of Europe. She has just begun her research, but is already fascinated by tales of ghosts wandering the windswept flats where bog bodies are found. “We’ve completely removed death from our societies. There’s no connection to it any more,” she says. “I think the more we delete it from who we are as humans, the more we become fascinated with past civilisations that had much closer links to it.” And for Humeau, this fascination is proving to be fertile ground.