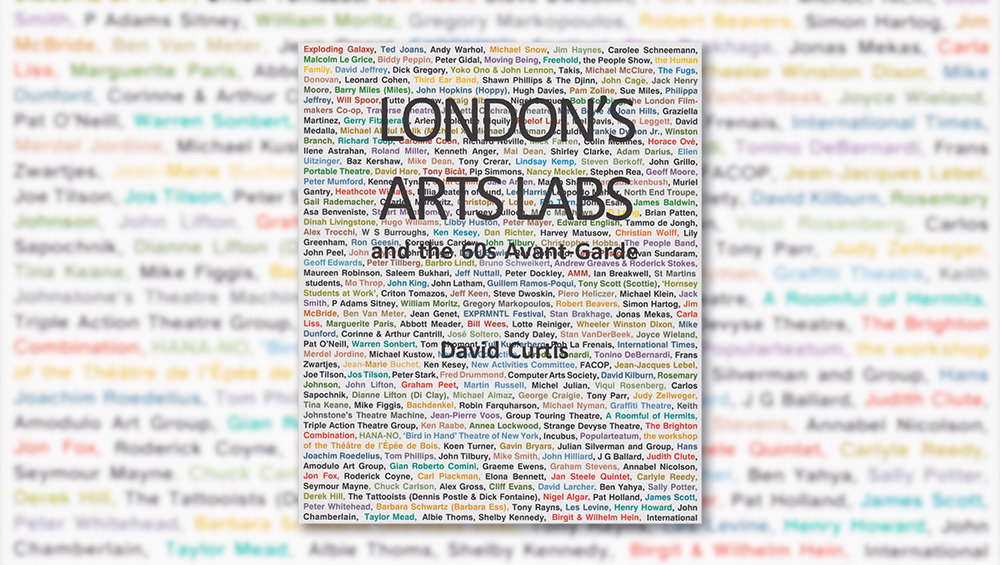

London’s Arts Labs and the 60s Avant-Garde, book cover, designed by David Curtis.

reviewed by CATHERINE MASON

If, like me, you missed the 1960s, but always wished you had been there, you will love this new book about an aspect of London’s alternative, experimental art scene, written by David Curtis, who was there. Curtis calls this “a memoir of sorts” and guides us expertly through the story of the two remarkable Arts Labs set up in London at the end of the decade. Curtis was involved with both labs and is a pioneer of British artists’ film and video, with a long career as a curator, writer and general enabler. Despite being associated with swinging London, the contribution made by the Arts Labs has been under-researched until now, with much material hidden away in archives.

Crammed with details of who did what, where and when, the book, says Curtis, is about “writing forgotten events into the record”. This is a welcome addition to the history of the avant garde and counterculture of the 1960s. In other words, more than just pop art happened during this highly productive decade, which was characterised by a questioning of identities and the general breaking down of social, cultural and artistic boundaries.

At the end of the 60s, London was emerging as a major international hub of underground culture. Don’t you wish you could have seen Biddy Peppin’s Giant Jelly, shown at the Roundhouse in 1967? This was a 34-gallon peppermint and almond-flavoured, purple and green-coloured confection into which a bystander flung himself naked, the jelly having collapsed as it was turned out from its mould on the floor. It instantly turned a private view into a “happening”.

This was a new type of art that did not fit into the traditional genres of painting and sculpture that the largely conservative art world was promulgating at the time. Indeed, most artists featured in the book were looking for an alternative to the commercial art world system of dealers and galleries. For them, the creative, often interdisciplinary collaborative process was more important than finished objects.

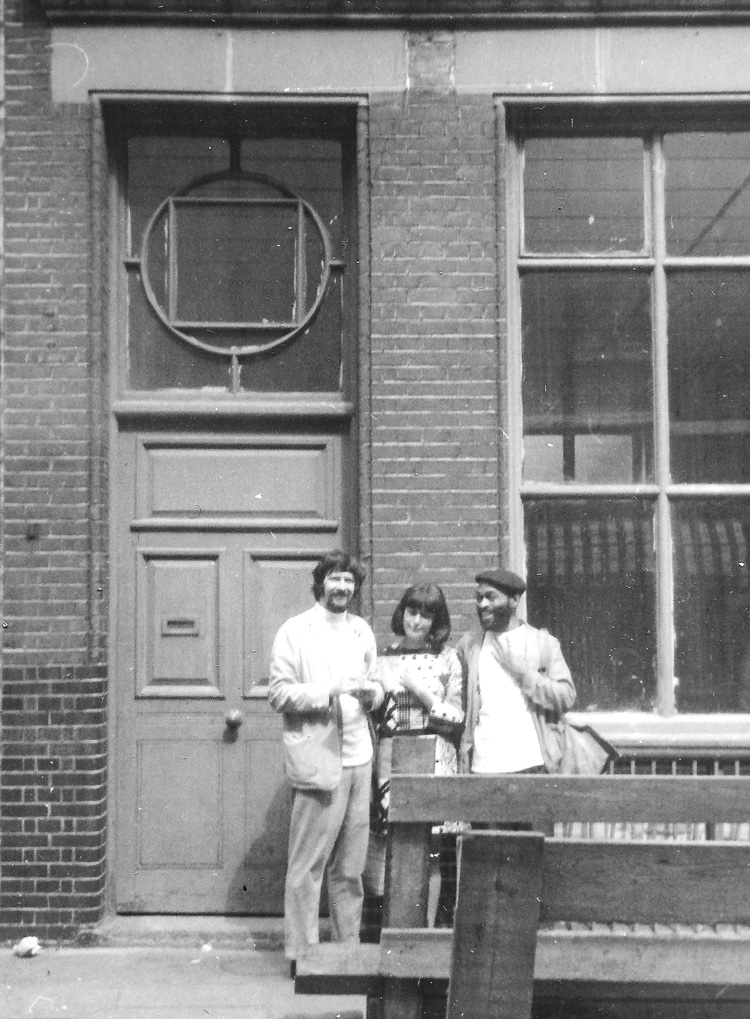

Photograph of Jim Haynes, Ted Jones and friend outside 182 Drury Lane in the Lab’s opening week, 1967. Courtesy Haynes archive, Napier University.

It was an American, Jim Haynes, who founded the first Arts Lab, in 1967, in Drury Lane, Covent Garden. Haynes was co-founder of the subversive journal International Times (IT) and had run a bookshop and the Traverse Theatre Club in Edinburgh before decamping to London. The name Arts Lab, which he came up with, chimed with the optimistic spirit of the times and seemed to have a wide appeal. A promotional leaflet stated: “You can eat a snack, watch a movie, see a play and a dance performance, buy a book, look at (or buy) a picture and argue your head off about the contemporary arts scene all under one roof.”

Haynes had a vision of making a place where humanity could be creative and hang out. He said: “Everyone came to the Lab; it was like a melting pot.” An extraordinary range of people used it, including Christine Keeler, Joe Tilson, Jim Dine, David Medalla and William S Burroughs. It was frequented by poets, writers and artists known and unknown. I particularly enjoyed hearing about the pensioner “Ginger” Wrigley, a local character who had been traumatised by internment in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, but felt at home among the young at the Lab.

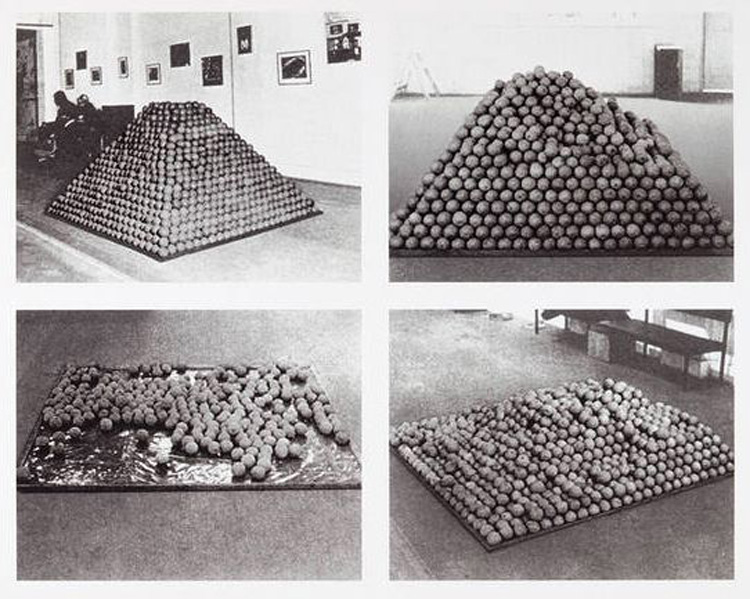

Roelof Louw, Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges), 1967. Arts Laboratory, Covent Garden, 1967. © The Estate of the Artist. Courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London.

Emphasising the laboratory aspect, the eclectic programme was developed and delivered by artists and practitioners using facilities on site – the activity was generating itself. It was unlike anything on view elsewhere in the UK at this time. Peppin and Pam Zoline ran the gallery and sought “exciting experimental work (you may define these terms) in any medium, art and non-art”. One of the first exhibitions was Roelof Louw’s conceptual work Soul City (1967), a “glowing, sweet smelling, six-foot high pyramid of oranges intended to be consumed by spectators”. Curtis tells us it helpfully supplied a lot of hippies with their daily dose of vitamin C. It is now in the Tate collection.

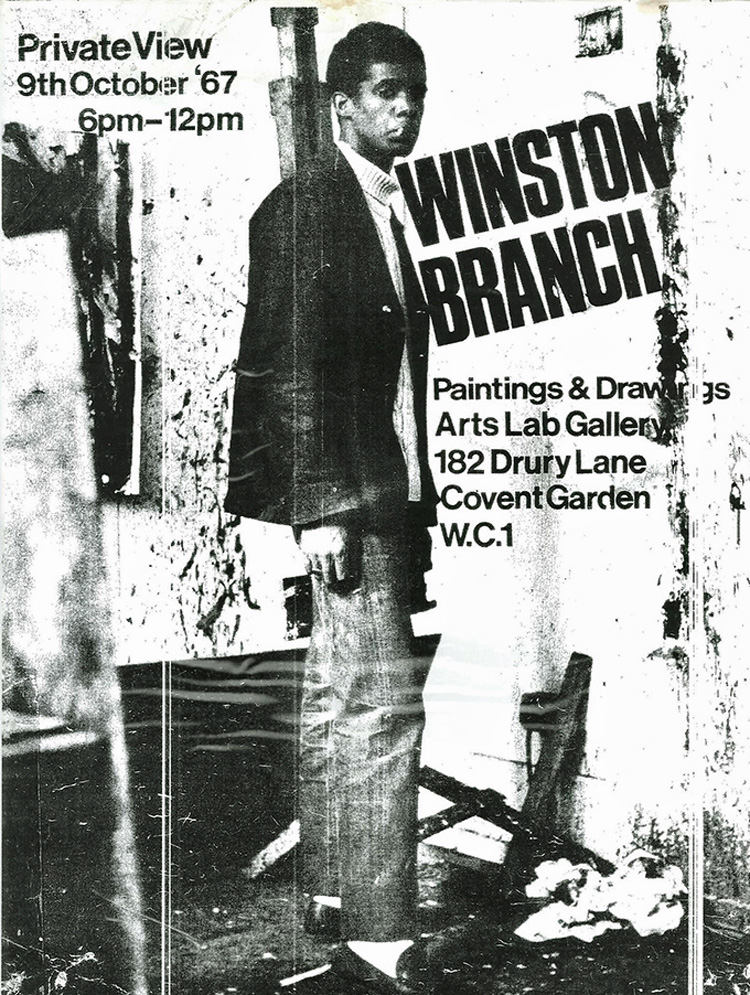

Winston Branch, poster design for exhibition, 1967. Courtesy Winston Branch.

Supportive of ethnic diversity, in its first year, the Lab held a “Black Power Week”, inspired by the London visit of the African American jazz poet Ted Joans. The week included a programme of films and the first show of the Saint Lucian-born British painter Winston Branch (who went to win the Prix de Rome from the British School at Rome in 1971 and now has numerous works in museum collections around the world).

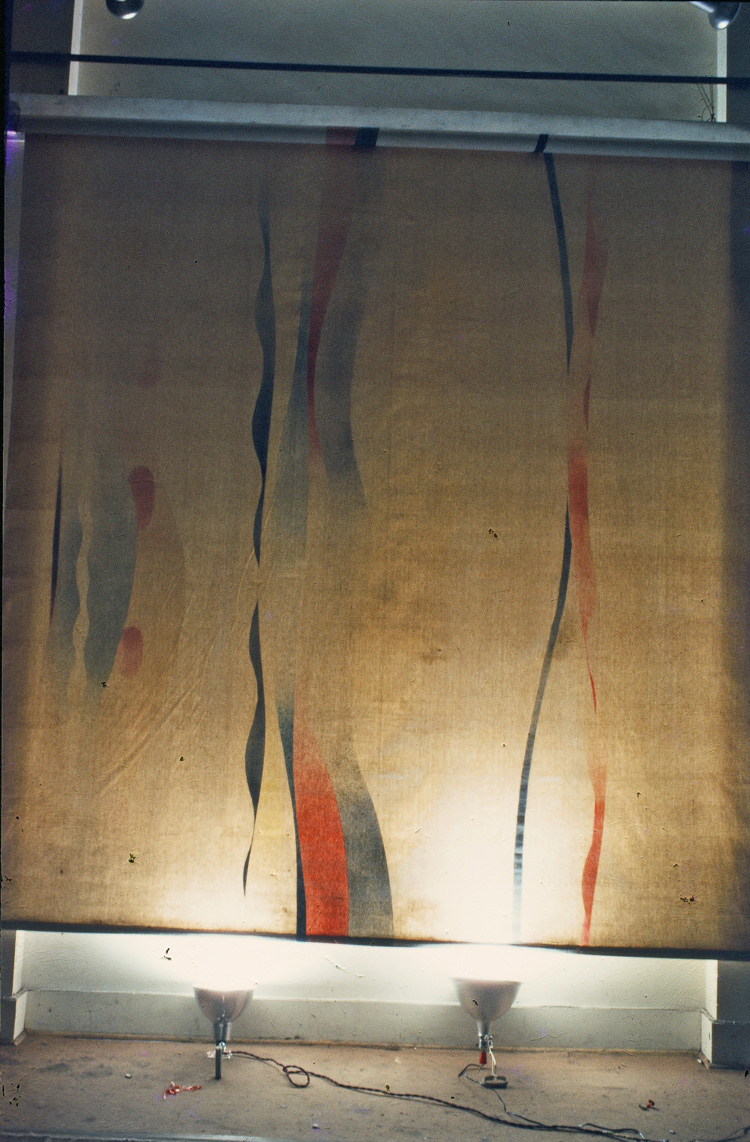

John Latham, Untitled (Roller Painting) 1964. Photo: David Curtis, copyright Estate of John Latham and Lisson Gallery.

Indeed, this book is full of “firsts”, another indicator of how important the 60s was to the development of art: the first UK performance of Erik Satie’s 24-hour piano piece Vexations (c1893), given by Richard Troop, who played the 840 repetitions of the same complex “motif” for 24 hours straight; Steven Berkoff’s first solo appearance as a writer/performer in 1968; and John Latham’s first public showing, in 1968, of Disappearing Images, his motorised roller blind paintings, which were designed to be seen rolled-up, rolled-down and all stages in between. Curtis points out that it is this type of work that appealed particularly to Peppin and Zoline as examples of art questioning the status quo, as well as being unsaleable. Nowadays, Latham’s estate is represented by the Lisson Gallery and his works are, in Curtis’s words, “prized, commoditised museum specimens”.

Lab-worker Dany Broadway with Takis, Signals, 1968. Photo courtesy David Curtis.

Also in 1968, the gallery showed John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s first joint show, Four Thoughts, AKA Build-Around, which consisted of found objects spread across the floor. Another first, the Greek kinetic artist known as Takis showed Signals (1968), inspired by the energy and movement of the flashing lights he saw around the city and in train stations. Signals went on to be an Arts Council touring show from 1970-71, and works from this series are now in the Tate.

.jpg)

Martinez, Boyles Sensual Laboratory, poster 1967, designer unrecorded. Courtesy Andrew Sclanders/BeatBooks.com

Dance performances included a co-creation between the Argentinian danseuse Graziella Martinez and the liquid light environment of artists Mark Boyle and Joan Hills’ Sensual Laboratory – a live light show of glass projection slides by Boyle (by the 80s, he and Hills were exhibiting as Boyle Family). This programme ran for 70 performances and appeared to include at least one featuring a young David Bowie (as dancer/mime), who appears on the poster. Bowie set up his own once-a-week arts lab at the Three Tuns pub in Beckenham.

Curtis himself was busy building up a repertoire of avant garde films, although there were few active film-making artists around in the UK at this point and initially he showed new work from the US and Europe, as well as classics (the Beatles donated a print of The Magical Mystery Tour as a gesture of support.) The film workshop was built up thanks to Malcolm le Grice, who took an unconventional approach to film-making. Castle 1 (1968) uses found documentary footage collected from Wardour Street editing-room waste bins. It is now considered a groundbreaking work of anti-cinema. Le Grice’s show Drama in a Wide Media Environment was probably the first gallery installation in the UK to explore the mixing of live and transmitted video imagery. It included a CCTV unit borrowed from Goldsmiths’ College, which he described as “two weeks of constant performance”. In the basement cinema, there was a soft floor with three shallow steps covered with foam and laid with carpet, which was perfect for lounging. Two matching 16mm projectors allowed continuous projection of feature films, including Andy Warhol’s twin-screen Chelsea Girls. Another taboo-busting film shown at the Lab was Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses (1964-68).

-photoshopped.jpg)

Chelsea Girls poster designed and silkscreened by Biddy Peppin, 1968. Copyright Biddy Peppin, Tate Archive, photo courtesy David Curtis.

A packed programme of events meant there could be three performances a night in the theatre, with one often starting after midnight. The London listings magazine Time Out, which so many Londoners relied on before the internet, started largely as a means of publicising the Arts Lab programme.

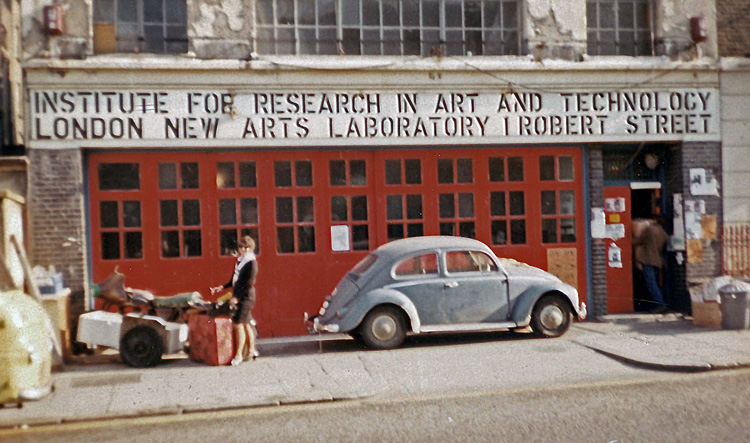

The Robert Street’s Lab red doors. Photo courtesy Pamela Zoline

By late 1968, deepening financial crises at the Lab and tensions among staff combined with policy issues led some, including Curtis, to feel that its artistic credibility was being comprised and, in late 1969, the Lab closed. Before this Curtis, Peppin, Zoline and others broke away to form their own New Arts Lab, and were joined by the artists John and Dianne Lifton, among others. In the spring of 1969, they moved into an empty factory in Robert Street, on a peppercorn rent from Camden council. An additional name, the Institute of Research in Art and Technology (IRAT), was devised, according to Curtis, to reflect the interest in exploring and widening public access to new methods and practices, including computers, video and a cybernetic theatre that would “attempt to bring about a close integration between live performance and technological equipment”. The groundbreaking exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity, which introduced many in the UK to the possibilities for computers and the arts, had taken place the previous year, and the Computer Arts Society held its inaugural show, Event One, in March 1969.

Le Grice ran the London Film Makers Co-op workshop and, by this time, Curtis had “the world’s largest catalogue of underground film”, according to a local press report. As well as rehearsal and gallery space, there were workshops for video (Britain’s first), for metal, plastic and printing, and the first freely accessible computer workshop for artists. Set up and run by John Lifton, this facility had a teletype connected to a remote mainframe computer by telephone. Used by many members of the Computer Arts Society, it allowed artists to write their own code.

.jpg)

Ian Breakwell in white overalls begins wrapping the sculptures with paper covered in the words UNSCULPT, at the New Arts Lab, 1970. Photo courtesy Mike Leggett.

Two shows in particular were indicative of the Lab’s attempt to free British sculpture from the mantel of Anthony Caro and the previous generation of establishment artists. John Hilliard and Ian Breakwell held a joint show of sculptures that were wrapped and then demolished by sledgehammer, the remains disposed of in a skip outside. This action was videoed and played back to the audience while a new sculpture made of scaffold poles was erected and painted with fluorescent paint in the dark so that the forms gradually emerged. In April 1970, JG Ballard had his first exhibition of sculpture, Crashed Cars, consisting of three wrecked cars, which proved a prelude to his 1973 novel Crash.

Avant garde art was supplemented with necessary “guaranteed earners”, such as Warhol’s Lonesome Cowboys film, which had its UK premier at the Lab (advertised on posters with the strapline, “May be a bit too much for many people, but that’s their problem”). The cinema proved to be the Lab’s primary source of income. Like the first Lab, there were problems with funding and very few staff were paid.

The Arts Council prioritised shows of well-known established artists, rather than new, experimental art forms that were not easily categorised and with results that were hard to quantify. It believed in a top-down approach into which arts labs couldn’t easily fit. Due to this, both Labs were short-lived. In 1970, this type of art activity could be controversial. The Daily Mail newspaper, for example, ran the headline: “They are giving away your money to spoon-feed hippy art.”

Ironically, the government funders eventually did take note, recommending that premises-based, artist-run laboratory type places were, indeed, worthy of support. Sadly, by the time the Arts Council geared up to such a concept, it was too late to help the Robert Street Lab and it closed with debts at the end of March 1971. But the legacy of both Labs remains as a model for other arts labs across Europe. By 1969, there were a dozen more labs scattered across Britain, each different, each independent.

Could an experiment such as the Arts Labs happen today? It is difficult to imagine in these times of a more corporate driven art world and career-minded artists. But the dominant presence that film, video and multimedia now plays within contemporary artistic practice owes much to the platform it received at the Arts Labs. This “experiment in co-operative organisation” reminds us just what was possible, even with very limited funds, thanks to a belief in the power of positive collaboration, a generosity of spirit and not a little hard work. Surely traits that are useful today.

• London’s Art Labs and the 60s Avant-Garde, by David Curtis, is published by John Libbey, price £25.99.