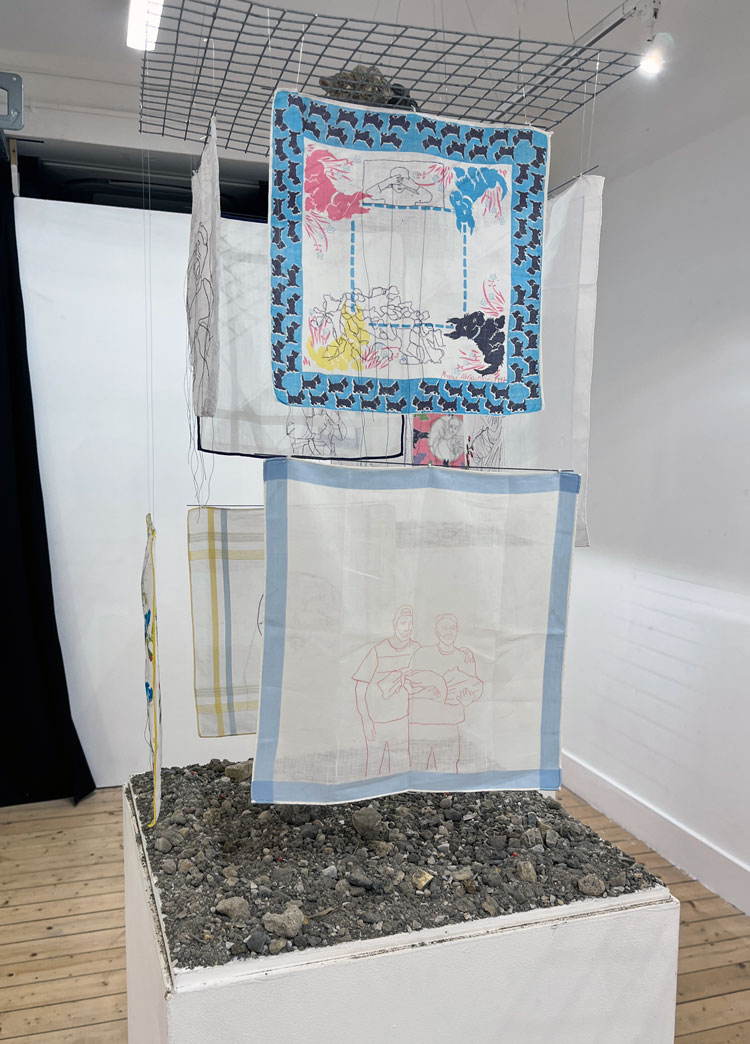

Beverley Carruthers, Hailstones, Bars and Meshes, 2025. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: © Jo Underhill.

Broadway Gallery, Letchworth Garden City

4 September – 18 October 2025

by ANNA McNAY

At its core, this is an exhibition about belonging and identity. It seeks literally and metaphorically to unravel the threads of familial narratives and to draw out the tales from archives and photo albums. It uses storytelling to draw the audience in, making us an implicit part of the narrative, calling up our own memories.

Four Cambridge-based artists – Beverley Carruthers, Bettina Furnée, Olga Jürgenson and Idit Elia Nathan – who have long been friends and critics of one another’s work, have come together, in what seems the most natural of fits, to create Leaving Were the Ones Who Could Not Stay, an exhibition that, in turn, seems to have the most natural of fits with Broadway Gallery, Letchworth, despite having premiered (in a smaller format) at Wysing Arts Centre last month.

Entering the gallery, we find ourselves amid the barrels and life-sized photographs of Scottish herring girls, Carruthers’ contribution to the multimedia exhibition. The herring girls were itinerant workers, who travelled from the tip of Scotland down the east coast of the UK every year, from May to December, following the herring boats, and then gutting and packing the fish ready for market. Carruthers’ grandmother was a herring girl until her 80th birthday in 1974. When they weren’t gutting fish, the women would be knitting the fishermen’s traditional jumpers, known as ganseys. And, according to where you came from, you would have a distinct gansey pattern, serving as a geographical signature.

Beverley Carruthers, Hailstones, Bars and Meshes, 2025. Inkjet and screen print with musical score, 80 x 200 cm.

The title of the installation, Hailstones, Bars and Meshes (2025), is borrowed from one of these patterns. The hailstones reference the harsh conditions the women had to put up with, and the meshes are the nets and the knitted patterns – the threads of their lives and stories. Carruthers has further used the bars and meshes of the gansey patterns to overlay the archival photographs of the women, like some secret morse code. She has also created a sound piece (Barrel Songs, 2025), emanating from the barrels, out across the whole gallery space (albeit listened to more clearly through headphones hanging from the barrels), comprising a song, O Whalsay Lasses, specially composed by Rowena Whitehead, and extracts from oral history interviews with the herring girls, which she has cut up and collaged to the “musical score” of a gansey pattern.

Idit Elia Nathan, Trigger Warning, 2023-25. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: Anna McNay.

Entering further into the space, we come upon Trigger Warning (2023-25), one of several works by Nathan. Set atop white plinths are carefully constructed hanging works, each comprising eight embroidered handkerchiefs, suspended from grids, above rubble, in which variously empty reels, thimbles, needle-threaders and so on are “mislaid”, echoing the chance items left behind by people running for their lives. The embroidery on the handkerchiefs primarily depicts imagery from the Gaza genocide, but this is interspersed with embroidered copies of works of art by artists such as Picasso, Käthe Kollwitz, Goya and Paul Nash, who have also produced imagery of war. Fluttering gently in the breeze, these delicate and intimate works on the one hand belie the tragedy they represent, and on the other hand they resound with the grief and sadness of loss and despair.

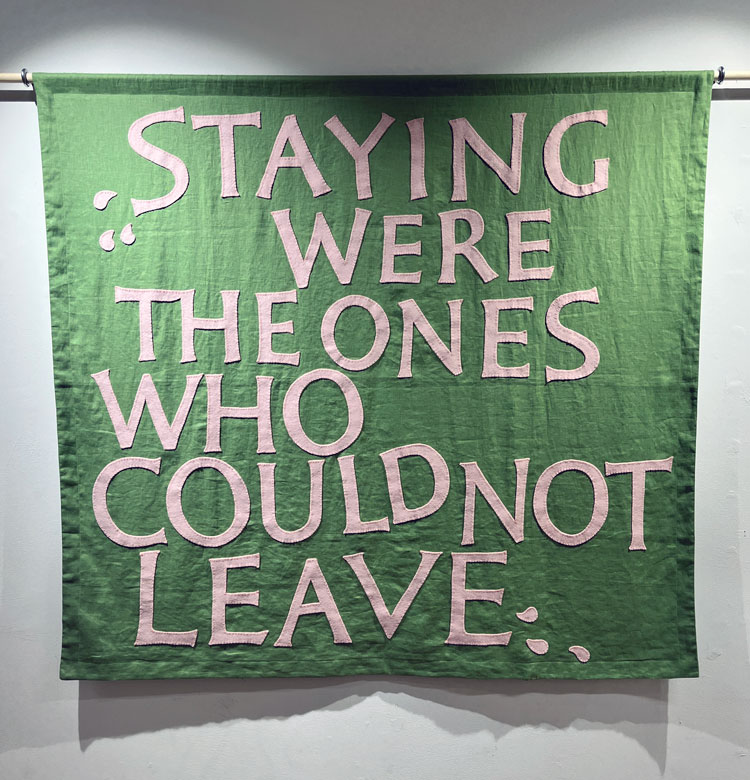

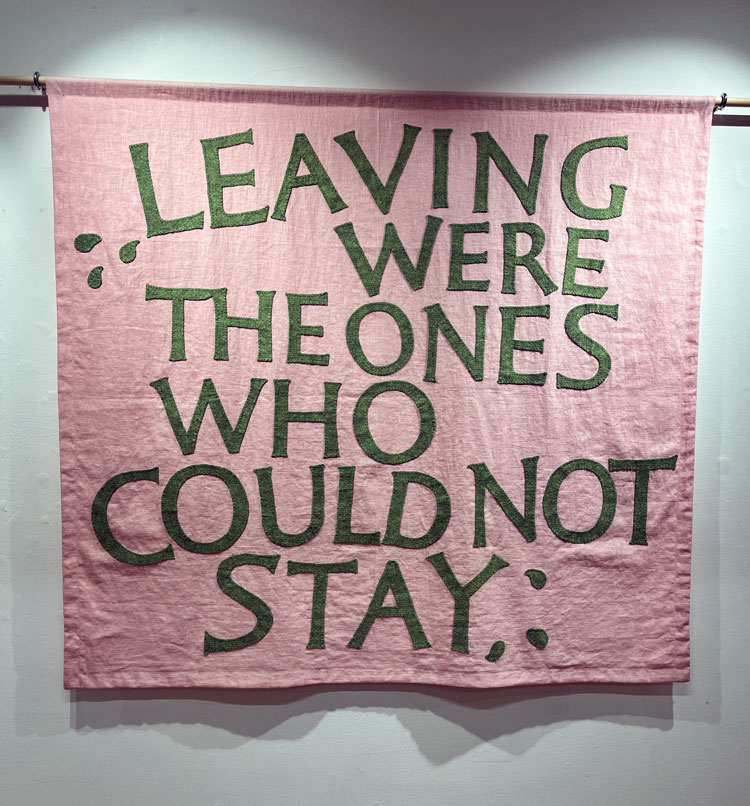

Bettina Furnée, Staying, Leaving, 2021. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: Anna McNay.

Bettina Furnée, Staying, Leaving, 2021. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: Anna McNay.

Staying, Leaving (2021) are two large appliquéd banners by Furnée reading “Leaving were the ones who could not stay” (the title of the exhibition) and its counterpart “Staying were the ones who could not leave”. The latter, the original quote, has been borrowed from Alexis Paul Gumbs’ M Archive, described on the wall text as “a non-linear feminist metaphysical text imagining post-apocalyptic existence” (I wouldn’t be able to put that in my own words if I tried!).

Bettina Furnée, Out of Our Earth, 2025. Three-channel video, 37 min. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: © Jo Underhill.

Furnée’s main contribution to the exhibition, a 37-minute, three-channel video and sound installation, Out of Our Earth (2025), picks up on the post-apocalyptic (although scarily it might not necessarily be so) concept of space travel and leaving Earth to visit – or stay – in outer space. In a post-screening event at Wysing, the author Ali Smith (a friend of the artists, who has also contributed a short story to Nathan’s Phone Home, 2020-ongoing) described it as: “A post-Covid mourning for the existentialism everybody felt across the planet, when we knew we were isolated, and we knew we were mortal, and we were being forced to understand it for the first time.” In response to the question: “Why would you want to go to space?”, she suggested it was “an excuse for us to completely destroy this world,” and, her partner, the artist and film-maker Sarah Wood, added, that it was proof of the extant colonial mindset. Jürgenson looked at it a little more philosophically, suggesting the film was an analogy for the afterlife. Certainly, the idea of belonging fed into the work, since Furnée recalled her arrival in the UK from the Netherlands, many years ago, and wondered whether the sense of not belonging she had felt in her home country might wane somewhat now that she was in a country where she officially didn’t belong. Having spent years living in Germany, this is a feeling I more than understand. Unfortunately, however, I don’t think “doing a geographic” has ever been the solution to existential unease.

Olga Jürgenson, Permission to Return Granted, 2025. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: © Jo Underhill.

Dealing overtly with nationality and nationalism, Jürgenson’s Permission to Return Granted (2025) explores the impact of forced collectivisation, Stalin’s terror and the second world war on the migrant Estonian community, including the artist’s family, in the Ulyanovsk area of Soviet Russia between 1929 and 1953. Motivated by Putin’s war of aggression against Ukraine, she began searching her family archives looking for how past generations had survived, in an attempt to find out how we can be expected to survive in the face of such atrocities today. What unravelled was an unexpected family tale, of a baby (Jürgenson) born in Siberia, who was moved to Estonia (still part of Soviet Russia at the time) at three months old, by a father who didn’t realise he was moving his family back to just where his ancestors had lived before migrating to Russia 100 years ago. This is a story of unknowns and of absences, and one which Jürgenson has collaged together, decking out the walls (wooden struts) of a house-like structure (migrant farmers lived in self-built cabins, which they needed to be able to disassemble and reassemble when forced to move on), with faces of fear, videos of a stream, and documents together with old cut-out archival photographs, showing the importance placed on the collective and the insignificance of individual lives.

Olga Jürgenson, Must Be Exiled to the Taiga, 2025 (detail). Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: Anna McNay.

A collaged wallpaper of newspaper cuttings, Must Be Exiled to the Taiga (2025), references a Russian folk ditty – stanzas of which are also in the collage, in both Russian and English – which Jürgenson’s great-uncle once recited in the company of his fellow villagers, earning himself 10 years in the gulag. The ditty criticises the forced collectivisation imposed on farming families. For example, one stanza reads:

We reap the rye and wheat by hand, / Then ship it off to feed the land. / Back home, the man has naught to eat – / He dines on weeds instead of meat.

Alongside this, a photograph of Stalin has been defaced and labelled “ghoul”.

Outside the house structure, Jürgenson also has the textile collages, Mobilised by Decree (2025), which include photographs of her grandfather, alongside photographs of his wife and children, which he might have liked to have had with him when he was sent to the Baltic coast to fight during the second world war. There are also photos representing experiences he did not want to talk about later: of Soviet prisoners of war captured by the Nazis, even though he escaped the concentration camps twice. The threads hanging loose from the cloths mirror those in Trigger Warning, relating two very different but sadly very similar stories of being forced to leave your home behind, face a nightmare, and not know how and when it will end, just that nothing will ever be the same again.

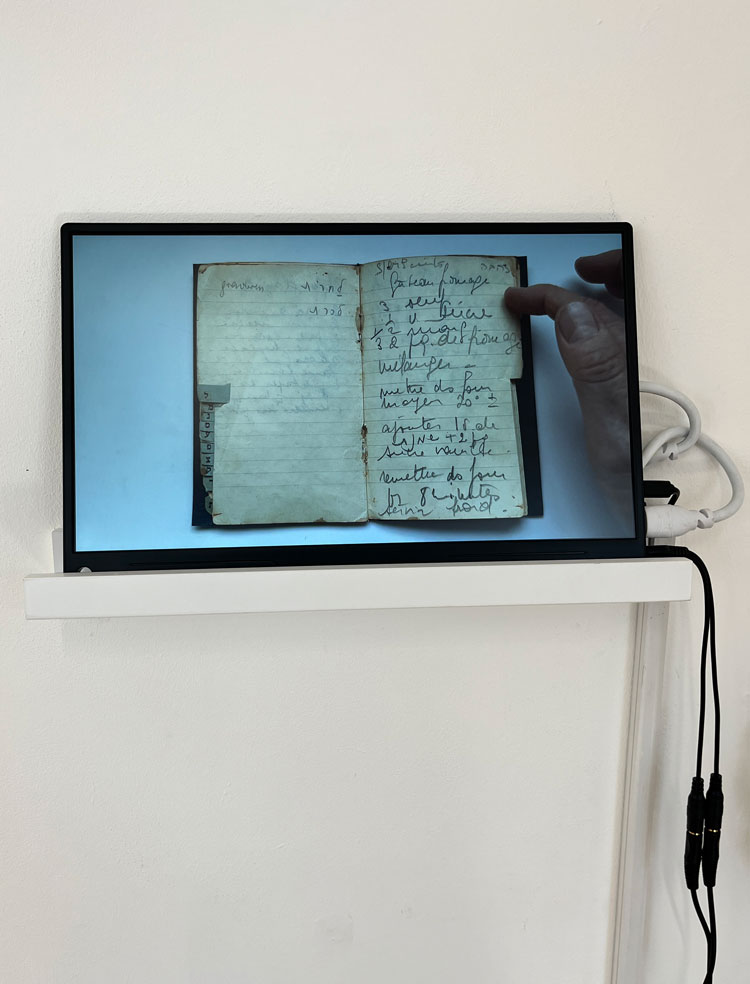

Idit Elia Nathan, Eva Learns Hebrew, 2025. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: Anna McNay.

Nathan has a further two works in the exhibition: Eva Learns Hebrew (2025) and Phone Home. The first is a short film showing a notebook originally belonging to Nathan’s grandmother, when she had to flee Germany, and was forced to learn a new language in Jerusalem. Thirty years later, Nathan’s mother used the same notebook when she left Belgium for the UK. In the film, Nathan and her mother read out some of the Hebrew vocabulary items interspersed among the French recipes. This confusion of four languages speaks volumes in terms of identity and belonging. The sound pieces in Phone Home are more abstract. Beneath a mobile of phone cards, there is a seat by an old-fashioned phone. Depending on the number that you dial, you get a different short story, read by its author. These range from Nathan’s own (first-ever short story) to those of six contributors (leaving a further three digits for more contributions!). In Wood’s tale, which is pervaded by homesickness, she speaks of nationalism and flags – truly relevant at this moment – and, again, of language as a barrier but also an identifier. Another option speaks of closeness and distance between neighbours, as well as the mother-daughter relationship, which, having just lost my mum, resonates with me.

Idit Elia Nathan, Phone Home, 2025. Installation view, Leaving Were The Ones Who Could Not Stay, Broadway Gallery, September 2025. Photo: © Jo Underhill.

All in all, this exhibition feels expansive but unified, pessimistic but full of hope. Where one thread breaks, another begins, and the result is a collaged picture of life and lives, of individuals, of families, of nations, and of humankind.