Katya Kvasova.

by ANNA McNAY

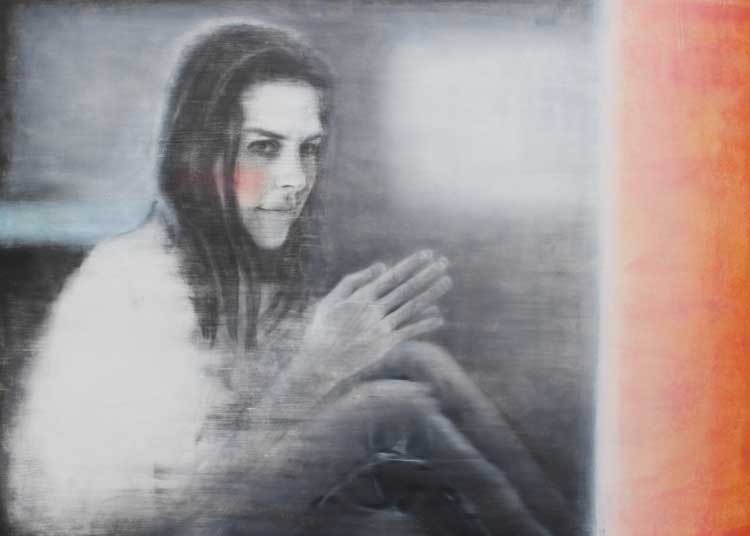

Katya Kvasova (b1980, Riga, Latvia) makes portraits of women. They are not necessarily portraits of the individual sitters, but rather capture their emotions – emotions that Kvasova must, herself, be able to relate to while creating the work – and a sense of the female experience, with its power and its vulnerability, as a whole. Most recently, and for the works on display in Hands are for Touching at the Saddleworth Gallery and Museum, her first UK solo institutional exhibition, she has been focusing on body language and, specifically, hands, for all that they can carry and convey.

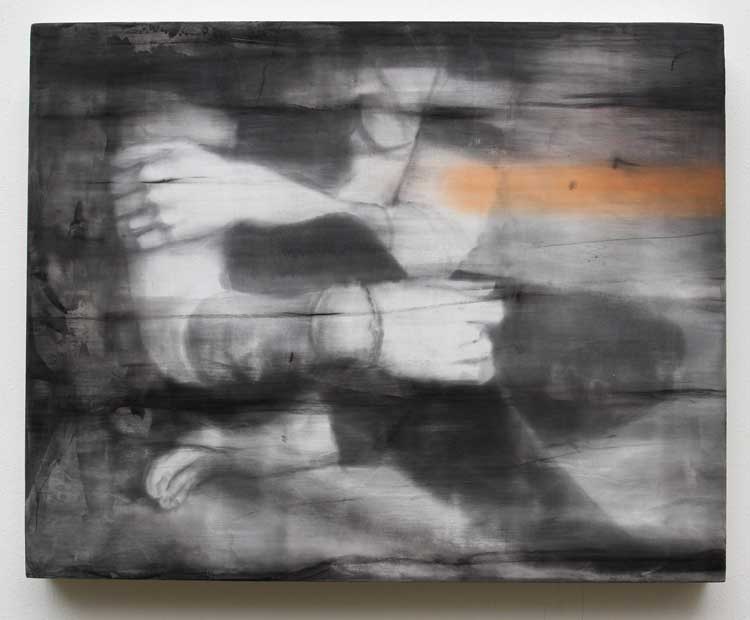

Katya Kvasova. Bloodlines N2, 2016. Mixed media on paper, 47 x 60 cm. © the artist.

Kvasova’s personal history feeds into her work, too, with one series in particular, Bloodline, drawing from old photographs of her mother, who died when Kvasova was just 12. This interest in capturing the aesthetic of photography, and of letting “the light eat the image”, is key to her style, which comprises a layering of graphite powder and translucent colour, to trap images and create a hazy sense of mystery.

In this Zoom interview for Studio International, Kvasova talks about her process, her background and her current passion (and necessity) for curating.

Anna McNay: Your practice concentrates on the female experience, largely comprising portraits of women, often focusing on their hands and body language. Can you expand a little on this? What is it particularly about hands that attracts you?

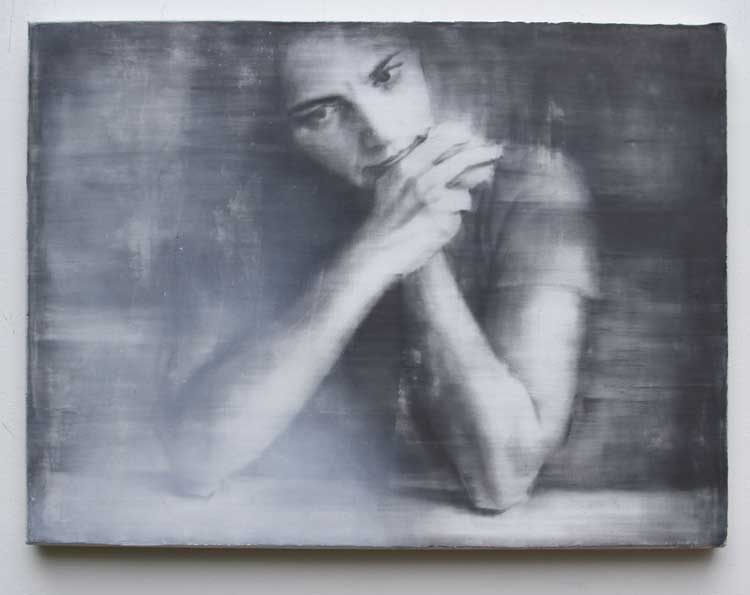

Katya Kvasova: My interest in hands and body language started fairly recently. I have one friend in particular who holds her hands in a special way, and, whenever I see them, I know it’s her. If someone were just to show me her hands, I would recognise her. I started noticing other people doing similar things, and so I began thinking about how we can see emotion in someone’s hands and body language. I was also looking at artists’ hands, because we’re makers, and everything we do is in our hands. Also mothers. What I remember of my mum is mostly her hands. She was always doing things for us: cooking, knitting, sewing, mending our socks, stroking us … That’s why I shifted my focus somewhat on to hands, rather than solely the face. The face is also interesting, of course, we can’t dismiss it. And I’m not saying I’m going to focus on hands for the rest of my career, but it’s amazing how much there is in them.

Katya Kvasova. Bloodlines N9, 2018. Mixed media on paper, 39 x 57 cm. © the artist.

AMc: When you say you are looking at the female experience, is it more of a generic female experience, as you have just described, with motherhood and things that women typically do, or is it the experience of each individual sitter?

KK: It’s both. Some sitters I know more closely than others. Sometimes I can link the visual with the character I know, and sometimes it’s more mysterious. There is one mother at my children’s school who I barely know, but everything about her look and her hands is just so mysterious, and it attracts me, but I don’t know why. When I look at the way she is, I can only imagine what her life is like, and all the experiences she might have had up to this point. They are all there. We can read them partially through images.

AMc: You have just touched on what I wanted to ask next, namely what is it that attracts you to a specific sitter? How do you select them, and is it important to you to get to know them a bit first? From what you have just said, obviously not always.

KK: No, not always, you’re right. At the moment, I’m running out of images to work from, and I’m asking myself what to do next. Where do I find more? Sometimes, it’s just a coincidence. I see someone, and I ask them. When my kids were in primary school, I was among a lot of mums outside the gates, and I knew more people there. But now they’re in secondary school, it’s a bit more tricky. I don’t know where it’s going to lead me next, but life brings interesting people to me. I have never known where my next sitter was going to come from.

Katya Kvasova. Holding, 2021. Mixed media on board, 24 x 30 cm. © the artist.

AMc: You say you’re running out of images. Does this mean you don’t have a sitter sit for you while you draw and paint them? Do you use photographs?

KK: Yes. It would be too emotionally taxing. I have tried it, but it didn’t suit me, because I’m a very anxious person. I realised I can’t work in anyone else’s presence. Even as a teenage girl in art school, as soon as the teacher came up behind me to look at my work, I would stop and wait until he had gone. Also, imagine sitting for two hours. A person’s thoughts wander, and their emotions change, and obviously their position changes. It would feel superficial to try to draw from this. I like to catch a moment. With photographs, you can take many, and, in some of them, there will be certain angles that just work.

AMc: In a way, your photographs are your preliminary sketches, then?

KK: You could say that. But I usually ask the person to not be present with their mind. For me, it’s important to portray their privacy. It’s not a dialogue, or, rather, it’s an internal dialogue. When I ask someone to sit for me, I ask them to imagine they are by themselves as much as possible, or to remember how they usually sit, when they are by themselves, or what do they do with their arms. Some people are more relaxed, they can do it better; others just can’t. I have friends I look at when we see each other at dinners or whatever, and I see the beauty in them, and I see the potential, but when they’re in front of the camera, it’s just gone. It’s not there, because they’re too uptight. Not everybody can do it, unfortunately.

Katya Kvasova. Irishka, 2021. Graphite and gesso on canvas, 30 x 40 cm. © the artist.

AMc: Do you try directing them and telling them what they normally do?

KK: Yes, but it never works. If they can’t relax and switch off their mind, it never works.

AMc: You refer to your works as portraits. Do you consider them to be portraits of the individual?

KK: That’s a really hard question, as is deciding whether they are paintings or drawings. They’re portraits of emotion rather than of a certain person, but it’s important for me to get a visual likeness at the same time. So, I don’t know.

AMc: When you’re making them, do you identify with the emotion you are portraying, or is it not that specific?

KK: You mean, can I feel the way they feel?

AMc: Yes.

KK: Yes, I think so. I think that’s why, when I go through my images (photographs), I choose the ones I can identify with. I’m a private person. I love being by myself. Most of the day I’m by myself. People say that whatever someone paints or draws is always a self-portrait. That’s true. That’s why I don’t do male portraits, because, for me, that’s foreign territory. I can do it formally, but emotionally I won’t be there, and so it’s not as interesting for me. Maybe at some point I will be curious, but, at the moment, I think my work carries more emotion if I can identify myself with it.

Katya Kvasova. Coral Side, 2021. Mixed media on canvas, 50 x 70 cm. © the artist.

AMc: What about your husband? Would you consider using him as a subject?

KK: Yes, I have done, and yes, I got the emotion because I know him so well.

AMc: Do you have a specific studio practice or routine?

KK: In terms of the hours I work, it’s when my kids are at school and before dinnertime. It’s very handy that my studio is in my house, but I have started to dream about having a larger space outside the house where I could go and not be distracted by all the housework. Ideally, I would love to work on a larger scale. I used to work on a larger scale, but then I had to reduce it. It’s easier to take smaller-scale work to different places, and even to sell it, but, ideally, I would like a larger studio and to work on a larger scale with more emotion.

AMc: Can you say a bit about your artistic training?

KK: I started early. At the age of 10 or 11, I knew I wanted to be an artist. I started art school as a young teenager in Riga – an after-school art school. I would finish my regular studies, take a bus to the art school and spend about four hours a day there. It gave me a very strong background. By the time I had to decide where I wanted to study next, I knew I wanted to leave Latvia. I was thinking of trying to do interior design, and I applied to the academy in St Petersburg. My teachers said I would most likely not succeed, because the art schools are very different in Latvia and Russia. They said they could train me and almost guarantee that I would get into the Latvian Academy of Arts, but that Russia had completely different rules and a completely different concept of art. The schools there look at your portfolio before letting you sit their entrance exams, and when I went to show them mine, they looked at my paintings and said that they were grisailles. In Latvia, they appreciated the subtleties in colour, but, in Russia, they wanted everything to be bright and screaming. It was such a shock for me.

I didn’t get into the academy. I went there and studied with tutors before the exams in order to succeed, but didn’t, as there wasn’t enough time to relearn everything. Instead, I went to Rostov-on-Don, in the south of Russia, and I was accepted into the architectural academy there, but I realised that wasn’t for me, either. I left after a year. But it taught me that you sometimes just have to do what you think is right. I allowed myself to be re-inspired by Latvian painters, and I decided I just wanted to paint. I was lucky enough to have my husband, who supported me throughout.

Katya Kvasova. About Time, 2020. Mixed media on paper, 53 x 74 cm. © the artist.

My studies at this time were basically watercolour and pencil. I still use both these mediums. I love their translucency. I never worked in oil then. I found some canvases and experimented a lot. Nobody really showed me how to use them properly. That is why my style was quite unusual back then. During those first three years, there were a lot of tears and a lot of self-doubt. My subject matter was mostly abstract. But there was always layering. There was always a lot of space, and there was always a quietness, which you could feel when looking at the work. I never did anything that screamed.

My friends said I should show my work to a gallery, so I found the best gallery in town, showed the gallerist my work, and she offered me a solo show. It was amazing. There were television reporters at the private view. I wasn’t ready for all that. They haunted me for months with so many questions, and I couldn’t paint for all that time. I didn’t like it. I got a lot of commissions, though, because some of the works I had shown were portraits. I had done some portraits of my little sister, so, for about a year, I kept getting commissions for children’s portraits. I earned some money, and they were in my style, with an abstract background, so it wasn’t all bad.

Then some American friends took my work out there, connecting me with an art dealer, with whom I worked for a few years, and I had another solo show in Ohio. It happened without my being there, though.

At some point, we moved to Moscow for three years, and then we came to the UK in 2007. I had a three-month-old baby, and so I couldn’t really paint as much as I wanted to until he started nursery. I was working on a series called Dolls in Dresses, which was very playful, exploring abstraction and my fascination with fashion, fabrics and over-layering of patterns. It started when I visited a museum in Moscow, where they have very old icons – so old that some of them have lost their colour and are chipped. I was touched and inspired by the simplicity of their composition – a central dark figure on a white background. It’s so present, so still and so calm, and something about it really struck me. It holds everything because it’s so strong.

sm.jpg)

Katya Kvasova. Small Hands 4, 2021. Graphite on board, 18 x 24 cm. © the artist.

At the time, I was listening to a lot of music by Björk, and one of her videos was about the crazy house where people were going mad. There was this ragdoll, with a very simple face, and so I combined the old Russian icons, a ragdoll, and my fascination with fashion. I was playing with huge dresses, layering them, and not really caring, because I wasn’t ready to do anything serious with a baby in my arms. I would just go and add another layer, let it dry, and then do another. I didn’t want to have to think hard about composition, because that drains you.

AMc: You have mentioned layering a number of times, as well as the distinction between drawing and painting. Can you say a little more about your process? The way you prepare the canvas and create the layers is quite specific now.

KK: I try to merge these two mediums, drawing and painting. Drawing, for most people, probably means using a line. But I use a sponge pastel knife, which I dip into graphite powder. You can do all kinds of things with it.

Katya Kvasova. What Are Your Dreams, 2020. Mixed media on paper, 47 x 60 cm. © the artist.

AMc: It’s a form of shading, in a way.

KK: Yes, it’s very soft shading. That way, you avoid lines, and you avoid the texture that you get when drawing with pencil. I always prime my canvases as smoothly as I can, so they resemble paper, but I also need to keep the absorbency at the right level. It’s not linear drawing, but it’s not vibrantly coloured painting either. It’s in between. I have tried using oils the way I use graphite – using a very thin residue of achromatic colour which I can then rub off or scrape away. It happened by accident, really, the layering. I made a drawing on canvas and covered it. Then I realised that I could take that layer of paint off, and my drawing would still be there, sealed behind the primer. I discovered that if you apply translucent layers of acrylic or watercolour on top, you can still see the drawing. You can even do another drawing on top, or add another colour, or cover it with white gesso. You can play around with the layers. Oils are exciting, but they make me anxious, because the primer absorbs some of the pigments, and then you can’t go back to white. If you use white oil, it seals it even more, and then it’s ruined. I could never repaint something with oils. I could only throw it away and start something new. I like the absorbency of the gesso, and how some pigments, when you only apply a residue, allow the white to shine. It gives you air and, again, this haze and mystery. I never do heavy applications. I’m thinking of moving even more into air. Imagine the light eating the image, like in an overexposed photograph. The light eats part of the image, and you are left guessing. That’s where I’m headed. When a work is almost finished, I apply acrylic glazing, and then I can play with oils on top. So, I can have everything; I can have my cake and eat it!

AMc: Talking about photography, can you say a little about your Bloodline series, which was inspired by old family photos?

KK: Yes, that’s a very specific body of work and a whole different conversation. They were all made on paper using graphite, and they mimic the quality of old black-and-white photos. I like the distortions. I like the aesthetic. When everything is pristine and glamorous, it feels fake, superficial.

Katya Kvasova. Bloodlines N8, 2018. Mixed media on paper, 57 x 46 cm. © the artist.

AMc: Bloodline is a very personal series. How much of your personal life do you put into your work? It is different from series to series, I guess.

KK: Yes. This one was all about my mum. She died young, and I didn’t have the chance to get to know her as much as I would have liked to. I was only 12 when she died. She had a life I didn’t know anything about, and that was really interesting for me. When I was looking at the photographs, it was as if I were looking at the same but also a different person. I was just so hungry, looking at her. I was looking and looking and looking, and then, when I was drawing, rather than feeling I was creating an image, it was more as if I were uncovering the image, as if this face were appearing as I was scraping off the layers. It was a very interesting experience – precious and very personal. I don’t know how people will react when I show the work, but I think that any strong feeling has relevance for others. If the feeling is there, then people can relate, right?

AMc: Yes, definitely. You are doing a lot of curating alongside making your own work right now. In fact, Between the Bars, a group show considering the significance of spaces and voids between objects, runs at Terrace Gallery, London, until 6 February. How did you get into this, and is it something you find complements your own work, or is it too time-consuming and draining? Do you want to keep doing it?

KK: I started doing it out of necessity. I never dreamed of being a curator, but, as I learned, we, as artists, need to initiate. When I came here, I didn’t know anyone, and I was outside the art scene. I didn’t see any other way in, because people usually get their connections through studying together or having their studios together, and I felt totally isolated, being here with my kids in my house, not even in London. I felt that curating would be my chance to meet artists. If I see an artist, whose work I like, I can’t just email them and say: “Let’s be friends.” But, if I have an idea for a project that they might benefit from, they are more likely to say yes to meeting or to invite me to their studio. As I say, it’s a necessity for me. I want to exhibit, and I don’t see any other way as yet. In the future, hopefully I will have invitations for other exhibitions, but, right now, it’s all up to me. I see a lot of benefits, apart from meeting new artists, though. I get to choose who I want to meet and who I want to exhibit. They also recommend other artists and spaces, and I learn to think differently about various subjects. There are a huge number of benefits, but it does require time. For me, the most difficult part is writing the proposal text. The other difficult part is finding the right space. I guess, if I were in London and mingling more in galleries, with other artists, I would know more spaces. I’m doing as many exhibitions as I can manage – about one a year. It’s enough, but it would be good to do more.

• Hands are for Touching is at the Saddleworth Museum and Gallery, West Yorkshire, from 22 January to 20 February 2022.

• Between the Bars is at Terrace Gallery, London, to 6 February 2022.