Judy Chicago: Revelations, 2024. Installation view, Serpentine North. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine.

Serpentine North Gallery, London

23 May – 1 September 2024

by VERONICA SIMPSON

Judy Cohen (b1939, Chicago) changed her surname to the city of her birth as a way of rejecting patriarchal branding, but think how differently it would have turned out had she been born in Des Moines. In the end, the cultural kudos of the windy city seems entirely fitting for her iconic status. And, boy, is her flag flying high right now.

She has just had a huge solo show at the New Museum in New York and now she has her biggest solo UK show at the prestigious Serpentine Galleries in Hyde Park, London. Not bad for a woman in her 80s whose work, until the last decade, was frequently sneered at by the art world elite (albeit loved by her community) for being too overtly feminist and unapologetic in its foregrounding of female bodies, body parts, issues and art media (specifically textiles). Judging by how many of the aforementioned body parts are displayed on the walls of the Serpentine gallery, the vulva is clearly now viable, and collectors and institutions are all over Chicago, from the looks of the moneyed hordes milling around the gallery at the preview.

Which isn’t to say that she doesn’t deserve to be in the spotlight. She absolutely does. Throughout her six-decade career she has been a pioneer in foregrounding women’s perspectives, celebrating the rituals, achievements and challenges of women in a still overwhelmingly male-dominated world.

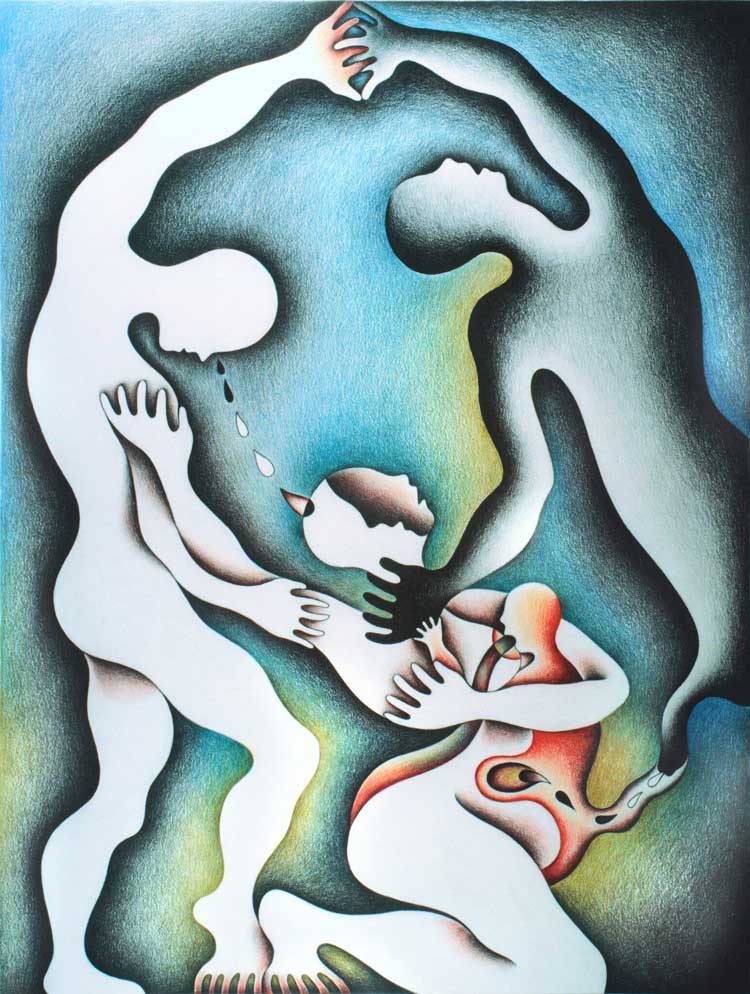

Judy Chicago. Wrestling with the Shadow for Her Life from Shadow Drawings, 1982. Prismacolor on rag paper, 29 x 23 in (73.66 x 58.42 cm). © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, NY Courtesy of the artist.

The work here, from the 1970s to today, reveals the distinctive visual language that has underpinned her activist adventures as well as her relentlessly inventive and curious spirit, refusing to be pinned down to any particular medium. In a recent interview in the Guardian newspaper, she reported a delicious quote from Anselm Kiefer after he had been given a private tour of her New York show: “He said: ‘Judy did what she wanted in her career. Not like me. I did the same thing over and over again.’ I thought to myself: well, that’s why you made gazillions. But I also thought it was true. I had five decades of uninterrupted art-making.”

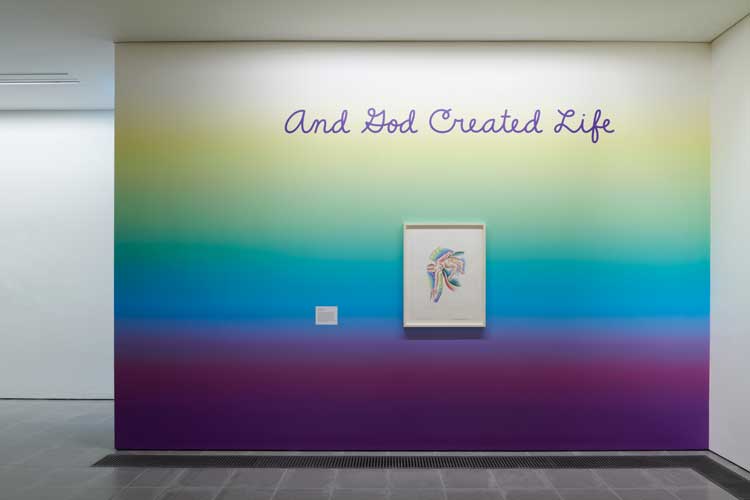

Tirelessly, Chicago has found her own way to manifest her vision for feminist art. As she so succinctly puts it in a work at the show’s entrance, as well as in her book Revelations (a manuscript developed in the 1970s but only now published by Thames & Hudson, alongside a luxury version by the Serpentine): “What is feminist art? It is art that reaches out and affirms women and validates our experience and makes us feel good about ourselves.”

Film footage and photos of Atmospheres. Installation view, Judy Chicago: Revelations, 2024, Serpentine North. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine.

Multidisciplinary, supremely experimental, unbothered by art world indifference, she created her own spaces for art, whether in women’s craft networks and community workshops or out in nature - her smoke drawings (Atmospheres) are especially inspired, wafting colourful clouds across the landscape, often accompanied by performance; these are represented in several photographs and films here. Lacking an official audience freed her, in a way, to collaborate and support women’s communities, encouraging their self-expression and imaginations, visualising what a world that recognises the validity of women’s contributions might look like. And, also, how a world free of toxic gender stereotypes might liberate all genders. Having studied at the Art Institute of Chicago and then the University of California, Los Angeles, in 1970, she founded the first feminist art programme at California State University, Fresno. It was hugely influential and many of the mature female US artists being celebrated in this post-#MeToo, women-friendly cultural landscape came through this programme.

But none of this would matter if the work – or much of it - wasn’t good. And mostly the work here is really strong, demonstrating her commitment to drawing, her deep research into the social and cultural systems and myths that either enable or denigrate women (but also restrict men), explorations of the connections between colour and emotion and, most of all, her consistent, indomitable spirit.

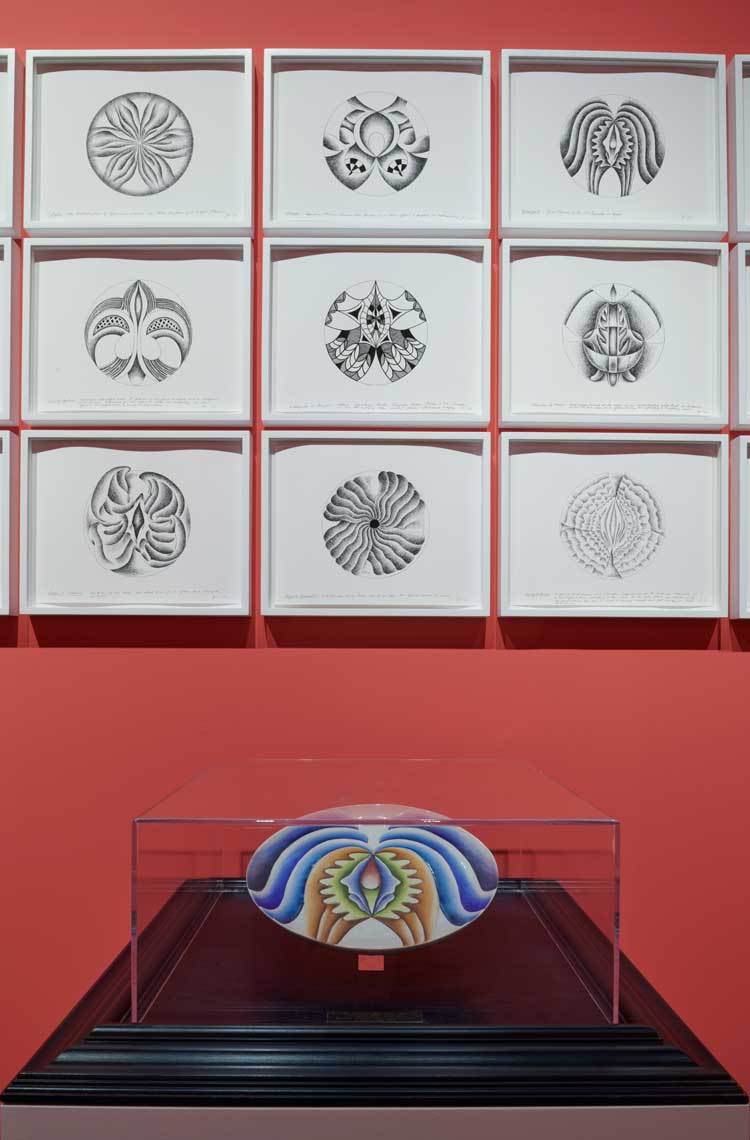

Judy Chicago: Revelations, 2024. Installation view, Serpentine North. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine.

Although there is an enormous and compelling wall-work on our left as we enter the gallery, we are encouraged to turn right and start at the chronological beginning. There are some questionable prismatic explorations here, but we are soon into her vividly evoked, graphic depictions of female/floral anatomy. Each area is colour-coded and themed along one of the chapters in her Revelations manuscript. These colour experiments are grouped, along with her vibrant, vulvic graphics, under the heading: Revelations of the Goddess.

Myths, Legends and Silhouettes. Installation view, Judy Chicago: Revelations, 2024, Serpentine North. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine.

Immediately beyond here is a room themed Myths, Legends and Silhouettes, dedicated to her seminal work The Dinner Party (1974-79). Here, she paid tribute to pioneering contemporary and historical female figures, as well as mythical women of the past with 39 individual named place settings: at each was a dedicated painted porcelain plate, featuring that trademark bold female/floral imagery. These were laid out in a triangular dining arrangement, with embroidered runners, a chalice, napkins and cutlery, and an accompanying floor work bearing the names of 999 additional women inscribed in gold. The work itself, sadly, isn’t here. It remains on show at the Brooklyn Museum where it is said to attract 100,000 visitors a year. But there are drawings showing the workings for individual place settings and there are some fascinating films, illustrating the impact of the work on her peers and her fans, and the impact on those who clearly weren’t her fans (a video of a congressional hearing at the time, shows a delicious amount of male outrage).

Judy Chicago, Smoke Bodies from Women and Smoke, 1971-1972. Remastered in 2016. Original total running time: 25:31. Edited to 14:45 by Salon 94, NY 2017. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo courtesy of Through the Flower Archives, Courtesy of the artist.

In the room beyond (The Yearning), we have Chicago’s investigations into pyrotechnics and the aforementioned, site-specific Atmosphere performances, of 1968 to 1974. Her “drawings in smoke” were intended as a “gesture of liberation”, releasing colour from the rigid confines of the page or canvas (at the show, you can download a free app to generate your own smoke drawings). If seen as a response to the emerging male-dominated land art movement, where gestures or structures were imposed on to the landscape, these are the opposite: ephemeral, exuberant and leaving no trace. The photographs and filmed footage are captivating, as Chicago and her colleagues, Faith Wilding and Nancy Youdelman, dance around the California desert, their bodies painted in vibrant pigments, often acting out timeless rituals while clouds of red or green smoke billow around them. Wilding and Youdelman were also participants in Chicago’s Womanhouse project (1972), in which a group of 21 teachers, artists and students occupied an abandoned Hollywood mansion as a celebration of female art-making.

The Calling of the Apostles and Disciples. Installation view, Judy Chicago: Revelations, 2024, Serpentine North. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine.

The boundary between art and propaganda is a fertile but problematic one when it comes to Chicago, which is made clear in the rear right-hand side of the gallery, themed The Calling of the Apostles and Disciples. When does a profound humanist message lurch over that boundary into simplistic or reductive caricature? While her artistry combined with righteous anger helps her to create explosive works revealing the links between violence against women and the overwhelmingly macho imagery of popular culture, with its relentless objectification of the female form, her depictions of men can seem more like grotesques. For example, in her series PowerPlay (1982-87), she overtly displays male anatomy in oppressive stances, such as Pissing on Nature (1982) a Prismacolor drawing of a man peeing into a sickly looking ocean. While this one, and a few others, have an iconic weight and clarity, others are somewhat puerile, more like schoolyard scribbles, of men grimacing, picking their noses and poking out their tongues. Far more profound are her Shadow Drawings (1980s) showing the tenderness, complexity, anguish and interdependency of male and female roles.

Visions of the Apocalypse, Installation view, Judy Chicago: Revelations, 2024, Serpentine North. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine.

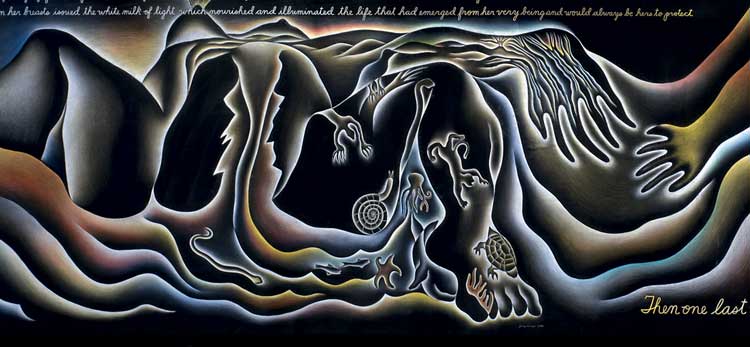

In the rear of the gallery, at the left-hand side, a section themed Visions of the Apocalypse gives us The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2012-2018). This is a powerful series of drawings depicting plants and animals in crisis that fascinate, with their intense, dark colourings, luminous outlines and handwritten messages. Equally powerful is a section of drawings and tapestries showing women giving birth, an act that should surely, as Chicago declares, be celebrated and venerated for its crucial role in human existence, rather than hidden away as messy and unseemly, or diminished to a mere mechanical act by its medicalisation.

Judy Chicago. In the Beginning from Birth Project (detail), 1982. Prismacolor on paper, 65 x 389 in (165.1 x 988.06 cm). © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Photo © Donald Woodman/ARS, NY Courtesy of the artist.

I am less impressed by a section that celebrates the house of Dior’s co-opting of Chicago’s flamboyant strain of feminism. There have been two collaborations with Dior, one entailed the staging of an entire couture show The Female Divine (2020) in her trademark colour purple, using decorative motifs taken from her Eleanor of Aquitane runner from The Dinner Party. There has also been a handbag range – several Lady Dior bags using Chicago imagery. There is nothing new about art being used by big business as a form of virtue signalling, but is it admirable? I would suggest a high-ticket, Chicago-designed handbag is surely the antithesis of female empowerment, however many powerful women’s names are embroidered across its glossy surface. But Dior is also one of the sponsors of this show, so I guess that is a hard conversation to have in a landscape of dwindling cultural funding.

Left hand wall shows monumental quilt What If Women Ruled The World, 2022. Installation view, Judy Chicago: Revelations, 2024, Serpentine North. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Jo Underhill. Courtesy Judy Chicago and Serpentine.

Collaboration is something Chicago has always championed, and aside from the Dior shenanigans, there is a heartwarming, albeit visually overwhelming interlude with a digitally enabled quilt of responses to a project What If Women Ruled the World? (2022), which Chicago ran with Nadya Tolokonnikova, the founding member of the feminist group Pussy Riot.

Just beyond this quilt, and the last piece in the show, is another zeitgeisty specimen: And God Created Life (2023), which shows a kind of hermaphrodite God, with both sex parts, reinventing the prevailing mythologies.

Judy Chicago: Revelations, Serpentine North Gallery 2024.

As I exit through the gift shop, I overhear a sales assistant explaining to a slightly stunned punter that each of the Judy Chicago limited-edition, Serpentine-published Revelations manuscripts is £5,000. He also told the punter that when the limited-edition range sells out, the prints are still available, but the price starts going up. (At time of writing, there were only three left). Goodness! There’s a format for maximising profits. Don’t get me wrong: I am glad Chicago is having her moment in the spotlight, and getting the credit and recompense she deserves. But the noise and fanfare and popularity around her art and her message might be saying a lot less about how far the world has progressed (gender-based violence and oppression are far from solved), and more about how quickly the machinery around her has managed to monetise that message while it has maximum traction. Which rather implies that this moment, too, will pass …