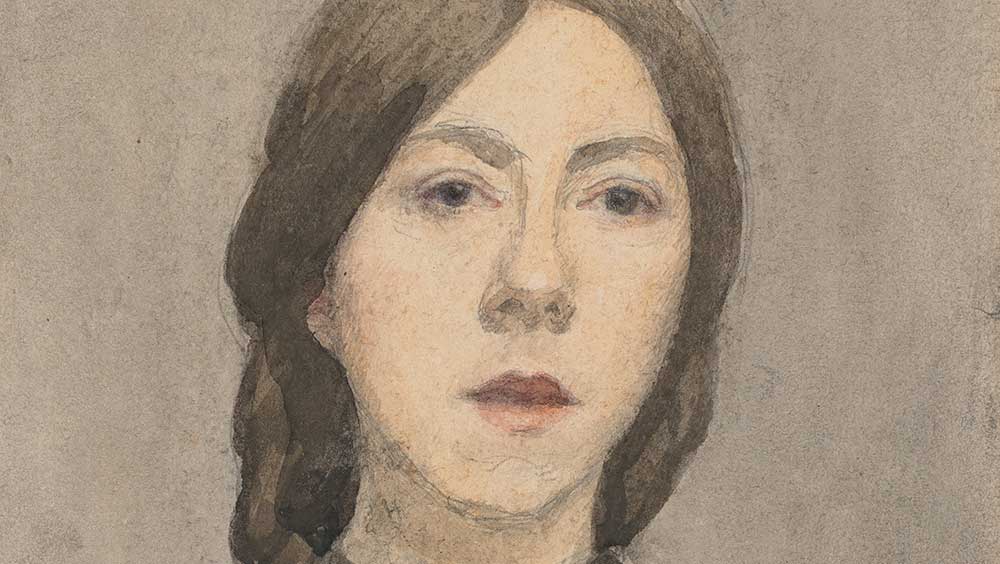

Gwen John. Self-Portrait with a letter, c1907-9 (detail). Pencil and watercolour. Musée Rodin.

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester

13 May – 8 October 2023

by DAVID TRIGG

Those who associated with Gwen John (1876-1939) in the London and Paris art scenes of the early 20th century would have laughed at the suggestion that she was a shy recluse. Yet this is the story that has been told about the British artist for decades. The myth of John sitting alone in a Parisian attic and having nothing to do with the world outside is a simple, even seductive explanation of her quiet interiors and reserved portraits. In Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris, curator Alicia Foster, whose new biography of the same name accompanies the exhibition at Pallant House, tells a different story, one of a driven, well-connected artist who, from the moment she left her home in Tenby, Wales, worked hard to embed herself at the heart of international modernism.

In 1895, John joined her younger brother, Augustus, in London at the Slade, which at the time was Britain’s only co-educational art school. The exhibition opens with a room of early works by John and her fellow students and teachers, including Elinor Monsell, Ida Nettleship (who later married Augustus John) and James McNeill Whistler. John’s student watercolour, Portrait Group (c1897-98), which depicts some of her circle relaxing in a Fitzrovia parlour, although lacking technical merit, already shows an interest in depicting figures in domestic interiors. Fast forward five years and she is now a competent draughtswoman living in Toulouse; a couple of striking red chalk portraits of her travelling companion, Dorelia McNeill, are not only technically adroit but elegantly convey her friend’s enigmatic persona.

Gwen John, Dorelia in a Black Dress, c1903-4. Oil on canvas. Tate: Presented by the Trustees of the Duveen Paintings Fund 1949.

The quiet interiority with which John imbued the women in her portraits is seen in Dorelia in a Black Dress (c1903-04), which owes a clear debt to Whistler, under whom she studied in Paris. The painting hangs alongside another portrait of Dorelia by Augustus John, who became her lover and lifelong partner. In Gwen’s portrait, she appears dignified and contemplative, whereas Augustus paints her as a sexualised fantasy: a rosy-cheeked maiden with an alluring gaze.

John moved to Paris in 1904, placing herself at the centre of the international art world. With no intention of moving back to London, it was here, she said, that she intended to “flourish”. Intent on living independently, even if this meant making material sacrifices, she became a life model to support herself. Through modelling, she met Auguste Rodin, with whom she had a long and tempestuous affair. Several sinuous drawings by the great French sculptor are included here, but next to John’s sensitive portrayals of the female form, they seem clumsy.

Gwen John, La Chambre Sur la Cour (The Courtyard Room), c1907-8. Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon

Collection.

It was in Paris that John took the first of her own rooms at 7 Rue Saint-Placide, a significant step that coincided with her pursual of the domestic interior as a central subject. The small painting La Chambre sur la Cour (The Courtyard Room, 1907-08) depicts a seated woman in a long black dress engrossed in her sewing, while a cat on a wicker chair enjoys the warm sun streaming through the tall Parisian window and lace curtains. Its softly daubed surface strikes a contrast with the meditative Vilhelm Hammershøi interior hanging next to it. Indeed, the warm and balanced composition makes the Danish painter’s interior look decidedly sterile and, nearby, Édouard Vuillard’s scrappy. John’s interiors speak to the independent existence she craved. These domestic spaces are not populated by wives or mothers (she never married or had children), but modern women ostensibly in control of their own lives and destiny.

Édouard Vuillard, Model seated in a chair, combing her hair, c1903. Oil on paper on board, Pallant House Gallery.

Through Rodin, John learned about the work of Paul Cézanne, which she greatly admired. His innovative new painting technique was partially developed in portraits of his young son, one of which is displayed in Chichester. Although John never produced anything quite as radical, Cézanne’s vocabulary of simplified forms and flat colour was clearly influential in the development of her style.

The village of Meudon on the outskirts of Paris would become home to John from 1911, although she kept her room in central Paris, which she continued to use as a studio. This new life was only possible thanks to the support of her patron, the American collector John Quinn, whose enthusiasm for her work ensured that it was included in the 1913 Armory Show in New York. The following year, Europe was at war and Paris was being bombarded. Yet John, as stubborn and resolute as ever, refused to leave and continued working in the city.

Gwen John, The Seated Woman (The Convalescent), c1910-20. Oil on canvas. Ferens Art Gallery: Hull Museums.

The war inspired her celebrated series of 10 paintings known collectively as The Convalescent (late 1910s – mid-20s), three of which are exhibited here. In each light and delicate scene, a lone woman sits still and pensive, reading a book or letter; they are poignant images of recovery with which everyone in Paris could relate to in the aftermath of war.

In the same year that John exhibited in New York, she converted to Catholicism. Signs of her interest in faith are detected in works such as A Lady Reading (1909-11), which recalls Renaissance annunciation scenes, but it was only after she swam the Tiber that religion became a central theme. As John’s beliefs became more conservative, her painting style grew more progressive. A whole wall of nun portraits from the 20s show John moving further away from her academic training towards a looser, patchier style inspired by Maurice Denis, who advocated for a modern approach to religious art. But unlike her more radical contemporaries, these still and dignified portraits eschew bold, bright palettes in favour of soft, chalky, muted colours with little contrast.

Gwen John, A Corner of the Artist’s Room in Paris, c1907-9. Oil on canvas. Sheffield Museums Trust.

According to John’s friend, the American poet Jeanne Robert Foster, the artist’s name was known to everyone in post-impressionist Paris and her work was the toast of the salons. Instead of withdrawing from the world, her engagement with the artistic developments of her day, coupled with her progressive view of womanhood, marked her out as a truly modern figure. While the figures she painted look isolated and reclusive, the evidence at Pallant House and in the pages of Foster’s rigorously researched biography suggests that John was anything but.

• Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris by Alicia Foster is published by Thames & Hudson, price £30.