Paul Benney, The Tenant, 2012. © Private Collection, London; Tony Oursler, Fantasmino, 2017, Collection of Tony Oursler. Photo: Julian Salinas.

Kunstmuseum Basel

20 September 2025 – 8 March 2026

by JOE LLOYD

Basel is haunted by ghosts – and not just by the shades of fallen gallerists haunting the Messe exhibition centre. There is the Spalenbeast, an exorcist corrupted with spectral energy who crawls on all fours, causes his victims to sprout buboes and sometimes turns into a pig. There is the headless David Joris, an Anabaptist heretic who died peacefully under an assumed name, then after death was dug up, tried and executed for his heresy. As late as 1929, the city was panicked by a knocking poltergeist that repeatedly immobilised a 10-year-old boy.

It is fitting then that the Kunstmuseum Basel has devoted a substantial exhibition to spectres, spirits and things that go bump in the night. Though the museum’s own ghosts seem to disagree: a few nights before the opening, To Repel Ghosts (2007) – a neon light work by Vittorio Santoro intended to ward off malicious revenants – puttered out and exploded (it was quickly restored). Curated by senior curator Eva Reifert with the advice from the British ghost historian Susan Owens and the German spirit photography expert Andreas Fischer, the exhibition surveys about 200 years of art about ghosts, ghost-related ephemera and art that uses ghosts as a device to explore sundry topics.

Susan MacWilliam, Where are the dead? 2013. Photo: Max Ehrengruber.

Ghosts have been with us for at least as long as the idea of an afterlife. Ancient Mesopotamians believed in gidims, echoes of the deceased that could escape the underworld and haunt their descendants. In the Hebrew Bible, the Witch of Endor summoned the spirit of the prophet Samuel to advise King Saul. Ghosts were not prominent in western visual culture, however, until the gothic vogue of the late 18th century and the Romantic movement that followed. Mythological and literary examples of ghosts became popular subjects for history painters – the oldest work on display here, by the American history painter Benjamin West, shows Saul and the Witch of Endor (1777) encountering a white-robed vestige.

It was around this time, too, that ghosts acquired their transparency and pallor, influenced by the phantasmagoria: a form of horror show that used magic lanterns to project spirits and demons. Suddenly, the supernatural could be conjured into the visual realm. The theatrical technique now known as “Pepper’s ghost”, where an illusory image of an object is projected on to the stage, became a popular fairground attraction. Ghosts became at once spirits of the deceased, objects of terror and sideshow amusements. This last has its descendants in the likes of Casper the Friendly Ghostor the young adult novels The Sad Ghost Club, where ghosts exist for our entertainment.

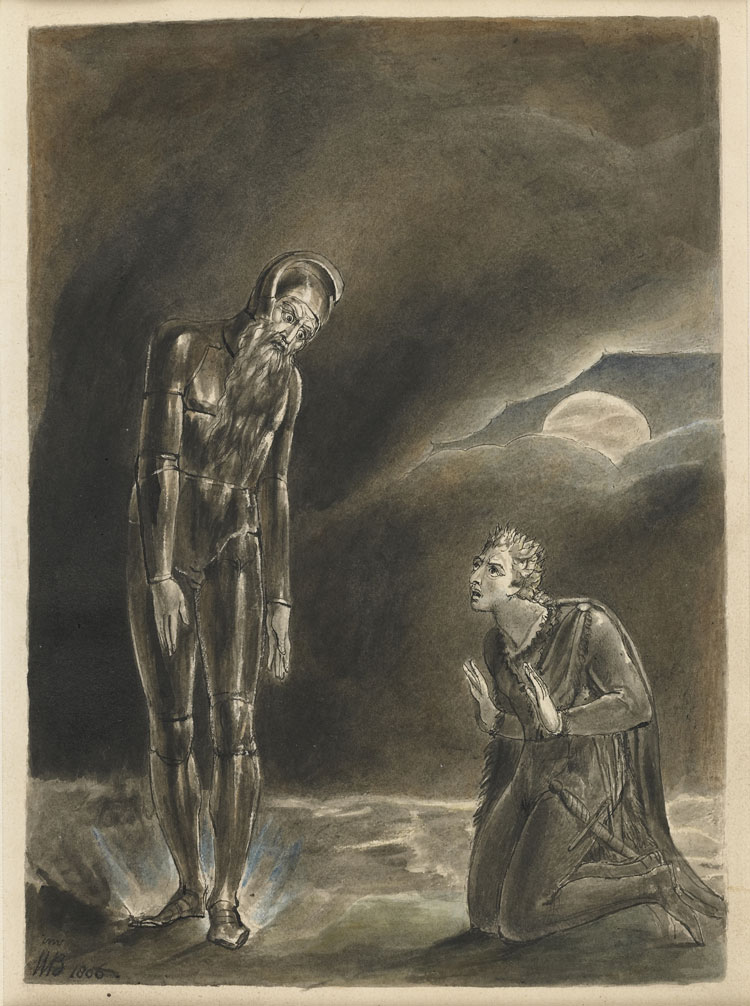

William Blake, Hamlet and his Father's Ghost, 1806.

For many others in the 19th century, ghosts were serious business. Death was all around. The prospect of contacting those yanked away by some sudden disease was appealing to many. This era gave birth to spirit photography – of which many fascinating examples are on show in Basel – where living people appear, joined by the phantoms of their loved ones. Many of these were money-making schemes. Others were more earnest. When he was not illuminating books or writing visionary poetry, William Blake practised as a medium. The Kunstmuseum has loaned a characterful drawing of iron age British chieftain Caratacus (c1819), one of the many historical luminaries that the poet seemed drawn to.

Georgiana Houghton, The Spiritual Crown of Annie Mary Howitt Watts, 1867. © Collection of Vivienne Roberts, London.

While we might assume that the rise of modern science and electric technology would blow away the paranormal cobwebs, it strengthened them. Telegraphs, telephones, radio and recorded sound all used invisible forces to aid communication. For mediums, the incorporeal world felt closer than ever. Many were talented artists, at least when guided by voices from beyond. Georgiana Houghton’s Spirit Drawings (1860s-70s) are astonishing collections of whorling, kaleidoscopic forms. A long, undated drawing by east London local Madge Gill (1882-1961), created under the influence of a spirit called Myrninerest, features a wall of faces emerging from textile-like patterns. French miner Augustin Lesage painted a Symbolic Composition of the Spiritual World (1923), a spectacular architectural fantasia decorated with elaborate motifs.

These figures were all marginal, cast as outsider artists (the German-born Agatha Wojciechowski, a decade younger than Gill, would buck the trend and be exhibited in her lifetime). Yet many respected figures wrote about their own encounters with the paranormal. Carl Jung attended seances, which he would later hold responsible for “the origins of all my ideas”. Once, while he was a student in 1898, a bread knife suddenly shattered into four pieces. He would keep the knife for the rest of his life, to remind him of unseen forces. In a 1923 letter, Thomas Mann described an encounter with a medium as a “completely convincing phenomenon”.

Ghosts, exhibition view, Kunstmuseum Basel, New Building. Photo: Julian Salinas.

Mann’s account has an erotic frisson, one not uncommon among ghostly encounters in the period. A c1927 sculpture by the Scottish symbolist George Henry Paulin, found in the dusty corridors of the Spiritualist Association of Great Britain, depicts a young female nude touched on the upper arm by a near-naked male spirit. Photos purporting to show ectoplasm – a sticky substance deemed to emanate from mediums in a trance – are often uncomfortably sexualised, particularly as the ectoplasm has a habit of exuding from the crotch. Little wonder that Mike Kelley, an artist of the irreverent and absurd, would later create his own Ectoplasm Photographs (1978), in which streams of cotton wool would emerge from his face.

Cornelia Parker, PsychoBarn (Cut Up), 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London. Photo: Julian Salinas.

Kelley is one of the postwar and contemporary artists featured to engage most closely with the history of mediums and manifestation. Another is Susan MacWilliam, whose disturbing video The Last Person (1998) restages the ectoplasmic encounters of the Scottish medium Helen Duncan, who in 1944 became the last person in Britain to be tried and convicted under the 1735 Witchcraft Act. Yet Kelley and MacWilliam share with many others an interest in the psychological aspects of ghostliness. The poet Emily Dickinson wrote that the human brain was more haunted than any house. Cornelia Parker’s PsychoBarn (Cut-Up) (2003) chops a replica of the Psychoset into pieces and hangs them along the walls. But although the house has been exploded, the sense of a lurking evil remains.

![Claudia Casarino, Desvestidos [Undressed], 2005. © the artist. Photo: Max Ehrengruber.](/images/articles/g/009-ghosts-2025/Claudia-Casarino-2025-09-16_s-nb-e2-r7-001.jpg)

Claudia Casarino, Desvestidos [Undressed], 2005. © the artist. Photo: Max Ehrengruber.

The most affecting room in the exhibition collects artists who use ghosts to explore human-inflicted trauma. In a work from 2005, Claudia Casarino has hung a set of diaphanous garments which float in the air like empty apparitions, juddering as passersby disturb the air. These forlorn, hard-to-place garments suggest the inherited trauma of their invisible wearers. Nearby, an Untitled 1922 text painting by Glenn Ligon sees the phrase I’m Turning Into a Specter Before Your Very Eyes and I’m Going to Haunt You reiterated down a 2-metre-long board. Gradually, the layers of text make the words invisible. The artwork re-enacts the process by which people with Aids disappeared.

Ryan Gander, Tell my mother not to worry, 2012. © Private Collection; Anish Kapoor, London. Photo: Julian Salinas.

For all this extending the ghost, the exhibition contains a good number of ghouls under sheets. Katharina Fritsch’s Gespenst und Blutlache (1988) is the most terrifying: a tall, thin polyester monolith that stands in an empty corridor, behind a pool of blood-red Plexiglas. Has it risen to avenge a violent act? Tony Oursler’s Pacman-sized Fantasmino (2017) is an anonymous cowl with moving digital eyes that oddly evoke sympathy. But perhaps Ryan Gander’s Tell My Mother Not to Worry (ii) (2012) – a funerary monument-like sculpture of a figure modelled on his daughter hiding under a bedsheet – best captures the ghost’s continuing contradictions. Does it depict a playful game or a mournful wraith, and should be we be afeared or affectionate? One day, we might all be such apparitions, gliding around, desperate for contact.