Duke Riley, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Praise Shadows Art Gallery. © Duke Riley. Photo: Edward Boches for Praise Shadows Art Gallery.

by MARIE POHL

Plastic bottles bobbing in the oceans, plastic bags hanging in trees, plastic cups tossed on the sidewalks of our streets, the invasion of single-use plastic is everywhere. Most people don’t think about it too much. It is inconvenient, and relationship issues, or health problems, job cuts, increased rents and rising living costs trouble their daily lives. But plastic pollution does trouble the Brooklyn-based artist Duke Riley, who confronts the unpopular truth about it in his exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash. Riley created an entire maritime museum featuring more than 250 artworks made out of plastic litter found in New York waterways, three films, large ink drawings, stunning mosaics, a wallpaper and a gigantic chandelier.

His show sends a loud message about one of the most pressing environmental threats. In 2017, the Center for International Environmental Law estimated that plastics could account for 20% of our oil consumption by 2050. Much of that plastic never arrives in recycling plants. It gets dumped into the rivers and oceans. About half of the Earth’s oxygen is produced in the ocean, mostly by plankton, which also capture carbon. Microplastics severely affect the development of plankton. Not to mention that microplastics are in the air now, so we breath in plastic.

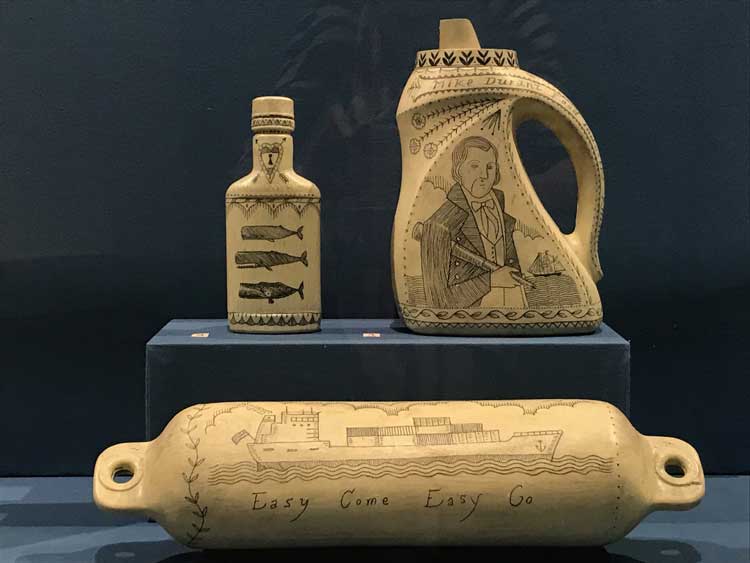

Political Pottery (selected items listed): Pitcher, c1805, unknown artist. Glazed earthenware, 23.8 × 22.4 × 10.2 cm. Brooklyn Museum; Bequest of Caroline Low and Charles T. Pierce. Photo: Brooklyn Museum; Right Pitcher, c1800, porcelain, enamel, gilding. Brooklyn Museum; H. Randolph Lever Fund; Plate, Netherlands, c1690, glazed earthenware, 34 cm, Brooklyn Museum, Museum Collection Fund; Napoleon Jug, 1895, porcelain, belleek ware. 24.8 x 11.4 cm, Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Dr Marion Reilly; Various scrimshaw objects by Duke Riley: Painted salvage plastic, ink and wax. From Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum, 2019-22. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view at Brooklyn museum: Photo: Danny Perez.

The singer Nina Simone said: “An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times. I think that is true of painters, sculptors, poets, musicians … I choose to reflect the times and the situations in which I find myself. That to me is my duty.”

Other artists have addressed the problems with plastic in their work. Singapore-based Tan Zi Xi takes the viewer underneath a blanket of plastic waste suspended from the ceiling in her installation Plastic Ocean (2016). Yet Riley adds another vital instrument to his environmental wake-up symphony, one that plays a significant part in much of his art: the historical lens. He challenges our perspective on the present by referencing the past.

Riley is mostly known for creating public spectacles he calls “public interventions.” In 2007, the artist was featured on the front page of the New York Post: “SUB MORON – Submarine nuts invade B’klyn ship.” Riley had been arrested for approaching the cruise ship Queen Mary 2 in a homemade replica of a submarine from the American Revolution. He later exhibited various artworks in his installation After the Battle of Brooklyn (2007) at Magnan Projects art gallery in New York. He was drawing a parallel between the US war of Independence and the US war on terror. The civil liberties Americans fought and died for were now under attack by national security measures such as the Patriot Act. On his website, Riley describes his role in the project as a “mythical liberator (who) resurfaces from the bottom of the harbour centuries later to restore a derailed national objective.”

Studio International visited the artist in his studio in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Riley’s studio is on the second floor of the Agger Fish Building that sits right on the East River, an enormous warehouse with corrugated-metal walls, cloudy glass windows and a giant, rusty hangar door.

On the day of the interview the warehouse is empty and a quiet, rainy Friday afternoon mood fills the big space. The silence extends into Riley’s studio. The artist is alone and working. He wears a knitted hat, a sweater and jeans. He looks like a docker, or a fisherman.

The SUB MORON New York Post cover is framed on the wall. A boxing bag swings from the ceiling. Old tapes are scattered across his desk. He is drawing on them. “We were doing a deep clean and I found a bunch of old tapes,” he says. “Rather than throw them out, because I don’t have anything to play them on any more, I decided to turn them into art. They’re going to be scrimshaw tapes.”

1: Duke Riley. No.355 of the Poly S.Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum, 2022. Painted salvage plastic, ink and wax. Courtesy of Duke Riley. 2: Unknown Maker, Scrimshaw Whale’s Tooth, circa 1830, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Museum Collection. 3: Unknown Maker, Scrimshaw Whale's Tooth, circa 1830-60, Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Museum Collection. Photo: Marie Pohl.

Scrimshaw is one of the many mediums Riley has mastered and works in. It references a tradition of art made by whalers that began in the late 18th century. On their long voyages, they would engrave pictures, portraits or lettering into whale bones, whale teeth or walrus tusks, accentuating their imagery with ink pigments.

Riley’s current exhibition features more than 200 scrimshaw works, blue and black ink drawings on stained bone-white plastic objects that he collected on beaches around New York city. The pieces include lotion tubes, brushes, a shuttlecock, a snorkelling fin, a single flip-flop, a legless lawn flamingo and a deodorant stick.

Duke Riley, set of three scrimshaw, No. 57-P, 37, and 81-P of Poly S.Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum 2019-22. Painted salvage plastic, ink, wax. Photo: Marie Pohl.

The plastic trophies are elegantly presented in glass cases in Riley’s fictional Poly S Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum. (Polystyrene is the petroleum-based material used for making plastic cups, packing materials and take-away containers, among many other things.) Next to his modern-day treasures, Riley placed a Napoleon mug from 1895, a plate from the Netherlands from about 1690, and other period pieces he chose from the Brooklyn Museum’s 19th-century scrimshaw and antiques tableware collection.

By setting these waste products on museum pedestals, he shows us what our society contributes to history. But rather than directing his criticism at the public, Riley directs it at a handful of individuals who are perpetuating the overload of single-use plastic. He refers to powerful businessmen, lobbyists and politicians by name. The fact that these wealthy and influential tycoons also fund institutions like the Brooklyn Museum, does not scare off Riley. Anne Pasternak, the museum’s director, fittingly described him to the New York Times as “the George Carlin of the art world”.

Marie Pohl: You depict CEOs of large corporations on many of your plastic containers. Why did you decide to portray them in the scrimshaw medium?

Duke Riley: When I was making a connection between plastic, fossil fuels and scrimshaw on whale teeth, or on other products made from whale bones during that time period, I was thinking about how these teeth are engraved with portraits of men who profited from the whale oil industry. You can see them in different maritime museums around New England, or really all around the world; they often depict the portraits of ship captains, or ship owners. Here in the north-east, it was usually prominent people of Nantucket or New Bedford. The people who are remembered today, who are immortalised, are the men that almost drove whales to extinction. I thought about how archaeologists will discover our plastic long after we’re gone, and that the people who are responsible for its existence should be immortalised on our bottles.

Duke Riley. Snorkeling Fin, No. 31 of the Poly S. Tyrene Memorial Maritime Museum, 2021. Painted, salvaged plastic, ink and wax. Courtesy of artist. Unknown maker, England. Bottle, circa 1750. Glass, sea animal encrustations. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Wunsch Foundation, Inc.

MP: You made portraits of: Mike Durant, president of the Food Industry Alliance of New York State; James Quincey, head of the Coca-Cola Company; Edward Breen, executive chairman of the chemicals company DuPont; and Ronald Sugar, a former CEO of the oil company Chevron, and currently on the boards of Apple and Uber. How did you choose your culprits?

DR: I did a lot of research. I will probably add more people as time goes on. Those men stuck out as the most noteworthy culprits for various reasons. Many of them have a lot of money and good PR. When you look them up, you find all this nice stuff written about them, all the good that they’ve done for the environment. You have to look into these things carefully.

MP: Did the whalers only portray rich profiteers?

DR: Not only. Some people who might have been very talented might have got paid to make certain portraits. There’s probably some of that. A lot of pieces also show maritime scenes. I thought a lot about that, too.

MP: You were born and raised in Boston, and grew up visiting places like the New Bedford Whaling Museum in Massachusetts. How long have you been doing scrimshaw?

DR: In some ways as far back as the early 1990s when I was in art school. I was tattooing folk art scenes on to dead fish.

MP: You are also a tattoo artist, which entails a similar kind of detailed, fine-lined drawing style.

DR: I built my own tattoo machine in 1991, and then I started studying under other tattoo artists around 1993. I have my own shop, in Greenpoint.

MP: You told the New York Times last year that the tattoo shop has allowed you to stay independent, “to not make any bad decisions”, by which you meant that you didn’t have to make bad art for good money.

DR: Yes, off and on I was always doing tattoos.

MP: Is it true that you live on a boat?

DR: For about half the year, and the majority of the work for the show at the Brooklyn Museum was done on a boat. I move around between Massachusetts and Rhode Island, pretty much from May through October. I make the scrimshaw and fishing lures on the boat. The bigger work, I make here in the studio.

MP: Do you fish a lot?

DR: We fish right here in the East River on our lunch breaks, and we eat the fish. In the fall, we were catching a lot of blackfish, tautog.

MP: You eat fish from the New York harbour? You’re not afraid they may be contaminated?

DR: I don’t think they’re any more poisoned than the meat people are buying that’s been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, which is loaded with hormones and drugs.

[Riley’s exhibition opens with a tutorial-like video, in which the artist teaches the visitor how to make a fishing lure. The show is installed on the fourth floor, where the museum’s period rooms are located. Before entering Riley’s maritime world of plastic, one passes a rococo revival parlour and a gothic library behind thick glass. Admiring the upholstered chairs, ornate table legs and mahogany veneer bookcases, one already hears Riley’s luring voice echoing from the video into the hallway – like a voice speaking to us from the future.

It is interesting to note that when these American Interiors (1850-80) opened in 1953, the Brooklyn Museum was the first major museum to present architectural settings from the second half of the 19th-century. The densely furnished period rooms stood in stark contrast to the minimalist fashion of the 1950s – they were even considered bad taste. And it was at that time that plastic began to flood into American homes. DuPont’s slogan called for “Better Things for Better Living ... through Chemistry”. In 1948, DuPont sponsored full-colour ads for Earl Tupper's tumblers manufactured from polyethylene, a plastic developed for insulating electrical wiring in wartime devices.

Seventy-five years later, in his three-minute film Welcome Back to Wasteland Fishing Episode One (2019), Riley holds a salvaged tampon applicator up to the camera and explains how to turn the plastic tube into a fishing lure. Then he gets on his boat, and we watch the artist catch a fish with this homemade-tampon-applicator-bait.

A pegboard exhibits a collection of these lures in a variety of colours, as in a real fishing store. Each lure comes with a small roll of fishing line; each lure also has a hook and that significant eye found on real lures. The eye enhances the lifelike illusion of the lure. Fish detect colour, particularly in clear water. They see short distances and use their vision to escape predators and find food. Riley cut the bottom of his tampon applicators into stripes so that they resemble tiny squid. He calls them High Low Fluke Rig Lures and titles the pegboard Duke the Fisherman’s High Quality Fluke Rigs Made in the USA™ (2022). (He seems to favour long titles.)

.jpg)

Monument to Five Thousand Years of Temptation and Deception (I), 2020. Salvaged, painted plastic and mahogany. Courtesy of the artist and Praise Shadows Art Gallery, MA. © Duke Riley. Photo: Will Howcroft for Praise Shadows Art Gallery.

The artist explores the lure motif even further in a series of wall case installations, such as Monument to Five Thousand Years of Temptation and Deception I (2020). Here, the lures are made from plastic forks, lighters, hair clips, combs, pop-on nails, or pregnancy tests as seen in Mother Ocean (2020). One can spend hours deciphering these objects, each armed with that catchy, deceiving eye. It’s a fun game. But the artist’s message is fierce.

Duke Riley. Mother Ocean, 2020. Salvaged, painted plastic. Courtesy of the artist. © Duke Riley. Photo: Duke Riley Studio.

The wall text explains that fishing lures were used in China and in Egypt 2,000 years ago. “It was an anthropological breakthrough when humans first harnessed another animal’s own predatory desire against itself to catch and kill it.” Today, fish misinterpret plastic litter for food, often fatally ingesting it. Our plastic is killing the animals we eat, and it is killing the ecosystems we need to survive. Humans are lured by the “convenience of cheap, disposable single-use items”, and we are “similarly trapped on a path to our own self-destruction”. Our societies are hooked on the lure of convenience like captured fish.

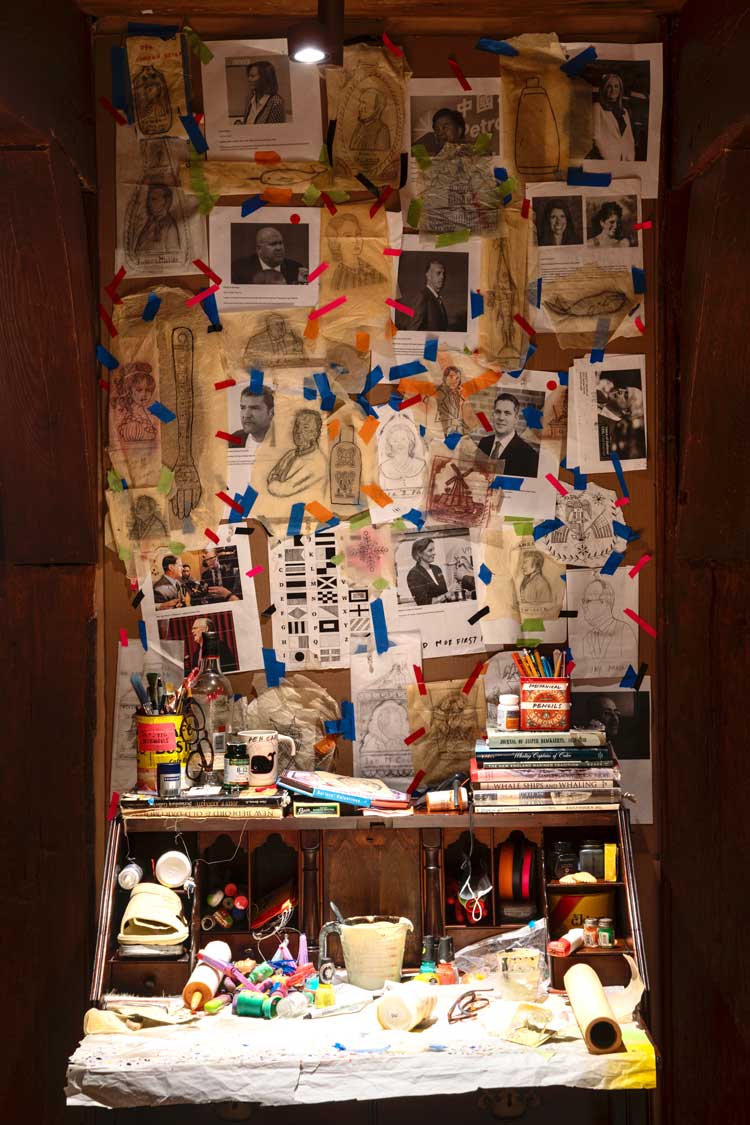

Duke Riley, Installation view of writing desk inside historical home, in DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash, Brooklyn Museum, 2022-23. Photo: Danny Perez.

Later in the show, a replica of Riley’s desk gives insight into the materials he uses to make these lures and his other works. On the wall behind the desk hang Riley’s notes and sketches, and pictures of various culprits, such as Governor Jay Nixon speaking out against the ban of plastic in Missouri. On the desk are a pile of colourful plastic objects, glue, pencils, several pairs of his glasses, a bottle of B12 vitamins and a pack of smoked oysters. Books are stacked on it too, one on New England maritime traditions, another on whaling, and a book about sailors’ valentines, which Riley has recreated as huge mosaics.]

DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash, installation view. Brooklyn Museum, 2022-23. Left: Sailor’s Valentine: Duke Riley, Order Here Prescription History, 2019, found plastic mosaic on panel, 168.9 × 168.9 × 10.2 cm, courtesy of the artist; Right: Sailor’s Valentine: Duke Riley, I am Delicious, Come on Get Your Money’s Worth, 2020, found plastic mosaic on panel, 170 × 170 cm, courtesy of the artist. Photo: Danny Perez.

MP: Why are the sailors’ valentines shaped like octagons?

DR: Whalers used to bring back these little octagonal boxes from voyages and give them to loved ones. Inside, they had little mosaics made out of seashells with messages of love. The whalers probably bought them at gift shops. It’s a sort of maritime folk art that I grew up seeing when I was younger and have referenced in my work over the years. As time went on, I began making larger versions of them. I used to make them all out of shells. Gradually, I started incorporating more plastic to reflect the beach conditions where I find fewer shells and much more plastic.

MP: How much plastic do you collect?

DR: In order to get the volume, enough colours to make a working palette, we sort through 20,000 tonnes of trash a year. We’re constantly sorting trash into different categories of shape and colour. When you think about the fact that many of those objects were probably made by other artists, who were paid by corporations to come up appealing designs for customers, it’s not a big surprise that you should be able to reuse them to make art that’s appealing to look at.

.jpg)

Duke Riley. I’m Delicious, Come on Get Your Money’s Worth, 2020 (detail). Found plastic trash includes dental picks, tampon applicators, syringes. Photo: Danny Perez.

MP: When did you start making art with plastic?

DR: I would say that for most of my work, before I even went to art school, I was always using salvaged materials to make art. I was trying to be resourceful. And then, my work has always revolved around the urban waterfront, the space where water meets land. Over the years, more plastic has been surfacing on the beaches and on the waterfront. There is a constant perpetuation in our society to produce more and more products. As quickly as people can think of banning old ones, new ones are being forced on us.

I started to think about all that along with climate change. Things started to feel like they were becoming more of an immediate concern in my own thought processes in my daily life. They started to take over the focus of my work. I witness the growing instability of the landscapes and the long term psychogeographical effect on the people in the surrounding areas. Then you see the weather patterns change, and you start thinking about how things will continue to change over time.

MP: You made a chandelier out of miniature plastic liquor bottles.

DR: The chandelier, yes, it’s not accurate to the period of the room it’s placed in, but I think it still fits. I wanted to do something that felt like an intervention into that room. I’ve always liked chandeliers. I love walking down the Bowery and looking into the windows of the stores selling chandeliers. I decided to make one out of little nip bottles [miniatures]. It’s the most common type of trash you find when you’re cleaning the beach. When I was a kid, they were all made of glass. Now it’s all plastic. But since the show has been up, people are pushing for a ban on plastic nip bottles in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut and New York. So, hopefully, we will be seeing fewer of them.

Décor à la Duke: doilies and Boozalier, a chandelier made from plastic liquor bottles. Photo: Danny Perez.

MP: The chandelier, Boozalier (2022), hangs in a room inside the Jan Martense Schenck house. You also exhibit work in the Nicholas Schenck house. These two 17th-century homes have the oldest architecture in the period room collection of the Brooklyn museum. Did you have permission to use these spaces freely?

DR: Originally, I was only supposed to do interventions inside the Schenck houses. But they were not accessible, visitors couldn’t walk into them. They were blocked off, and only had these little viewing windows. The idea was to maybe sprinkle some of my scrimshaw bottles around the living quarters. But you wouldn’t have been able to see them. Then the pandemic happened. The show was postponed for about a year. During that time, I was continuously making more and more work. We had several meetings and talked about expanding the show, giving it more impact. So, it just kind of kept growing and growing.

Installation: A historic home, now with everlasting plastic. Mosaic: Just Plain Forever, 2019, Shell mosaic on panel in mahogany, framed: 125.73 × 125.73 cm. Courtesy of Laura Lee Brown and Steve Wilson, 21c Museum Hotels. Photo: Danny Perez.

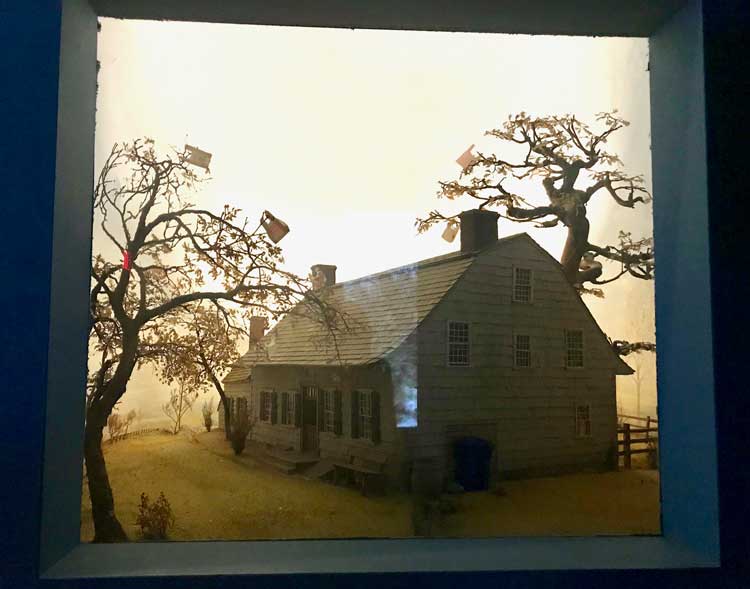

Albert Fehrenbacher. Model of Nicholas Schenk House, 1970. Modified by Duke Riley, 2021-22. Brooklyn Museum, prop1-29.1283. Photo: Marie Pohl.

MP: I found a very small work particularly moving, a tiny model of the Nicholas Schenck house, made by the German artist Albert Fehrenbacher, which you slightly modified.

DR: The model attempts to give context. You see the house on its original site by the water by Jamaica Bay, from where it was removed. I made miniature plastic bags, and some trash, and we hooked up a fan so the bags would be blowing in the breeze.

MP: Could you talk about Erika? That’s another powerful piece.

DR: Erika was the name of an oil tanker that sank off the coast of Brittany, France, in 1999 and dumped a lot of oil into the ocean. I was thinking about the destructive nature of fossil fuels, the insanity that goes on, trying to move liquid, whether that be fuel or bottled water, across the oceans, and the different catastrophes that happen around the world.

Erika, 2021. VCT. 162.6 x 254 x 10.2 cm. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Marie Pohl

MP: What is the white sky made from?

DR: The frame is made with shotgun shells and drink stirrers. The image itself is made of vinyl composite tiles. I used to go around collecting old tiles out of dumpsters in Brooklyn. There was a place called Bergen Tiles that closed down at some point where I raided the dumpster 10 years ago. I got boxes of these old tiles. Also, when they were renovating buildings around Brooklyn in the 90s, dumpsters were just filled with this stuff. I would collect it, more because it was cheap, but it is all plastic, and it was all destined for landfill.

Duke Riley, To Determine Whether or Not Things Were Getting Better or Worse, 2010. Ceramic, glass and vinyl composite tile on two wood panels, 83.8 x 289.5 cm. An Invitation to Lubberland, MOCA Cleveland, 2010. Courtesy of Duke Riley Studio.

MP: Mosaics make up an integral part of your oeuvre. There are especially beautiful ones in An Invitation to Lubberland, your exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland in 2010, another project in which history plays an important role.

DR: Most of my projects deal with ocean fronts. Then I was asked to go out to Cleveland. When I was driving around and exploring the city, I found this little inlet into the Cuyahoga River. Someone told me there used to be a hobo encampment from the 1850s to the 1930s, and that a serial killer had started preying on the hobos who lived alongside the creek, in an area called the Kingsbury Run. The city and Eliot Ness tried to catch the killer, but were not able to.

MP: Eliot Ness, the notorious prohibition agent who brought down Al Capone?

DR: Yes, but Ness could not catch the Cleveland torso murderer. So, he and the city decided to burn down the encampment and bury the Kingsbury Run underground. The river no longer exists, you can just sort of see an outlet where it drains into the Cuyahoga. The project involved a lot of research around that incident, which happened during the Great Depression. Part of it involved the census the US government used to carry out, to count how many itinerant hobos were travelling across the country, as a barometer to see how the economy was doing. I dressed up as a census man and went around by freight train, doing a sort of modern-day hobo census count and documenting the whole process. The other part involved breaking into the sewage system, and by using maps from the library, geological maps, along with Google satellite images and old city planning maps, I tried to figure out where the river went and follow it to its precipice. The project referenced hobo folklore and the Big Rock Candy Mountain. It was largely symbolic.

MP: How do you choose your projects?

DR: I have lots of different ideas. I’d say out of 10 things that I propose, write out, plan, or submit to some institution, probably one actually happens. I think, for me, with any art project, there has to be a certain amount of unknown. If I know the exact outcome of what I am doing, it feels like, what’s the point of doing it? There has to be a certain amount of stimulus or fear when going into something, so that you know it’s going to be worthwhile. It’s not that you know it’s going to be good, it’s more about what you don’t know. Then it’s something I want to do. I have to have some sort of feeling usually, with anything that I am doing, this could really be terrible, then I want to do it.

After the Battle of Brooklyn, 2007. Photo documentation of intervention. Photo courtesy of Duke Riley Studio.

MP: Like for your project After the Battle of Brooklyn (2007), where you re-enacted the world’s first submarine attack? You built a replica of the Turtle, a submersible vessel that attempted to attach an explosive to a British flagship during the American War of Independence. You steered your replica in the direction of the cruise ship Queen Mary 2. But you were arrested by the coast guard before you could reach the arriving ship.

DR: As an artist, you’re trying to push boundaries and push further into the unknown, and if it doesn’t feel like I am doing that it’s not the right project.

MP: You were arrested for terrorism?

DR: I was held for a little while. Not too long. I was sort of on a terror watchlist. The case is still open. When it comes to things that involve Homeland Security, they can just leave something open for as long as they want. It’s part of the Patriot Act.

MP: Do you run into the law a lot with your projects? There was this story about you infesting one of Donald Trump’s hotels with bedbugs?

DR: There was a project that was made. A corporation was formed and bought by another corporation, which was bought by another corporation and one of those corporations produced a film that happened to take place in a Trump hotel. That film may or may not have involved live bed bugs. Any problems that may have occurred due to that film company’s production probably should be taken up with that film company. That’s about all that I know about it.

Stills from video I (Havana). Number 1 of three-channel-video documentation of cigar smuggling for Trading With The Enemy, August – November 2013. Photo: courtesy of Duke Riley Studio.

MP: Another outlaw project was Trading with the Enemy in 2013.

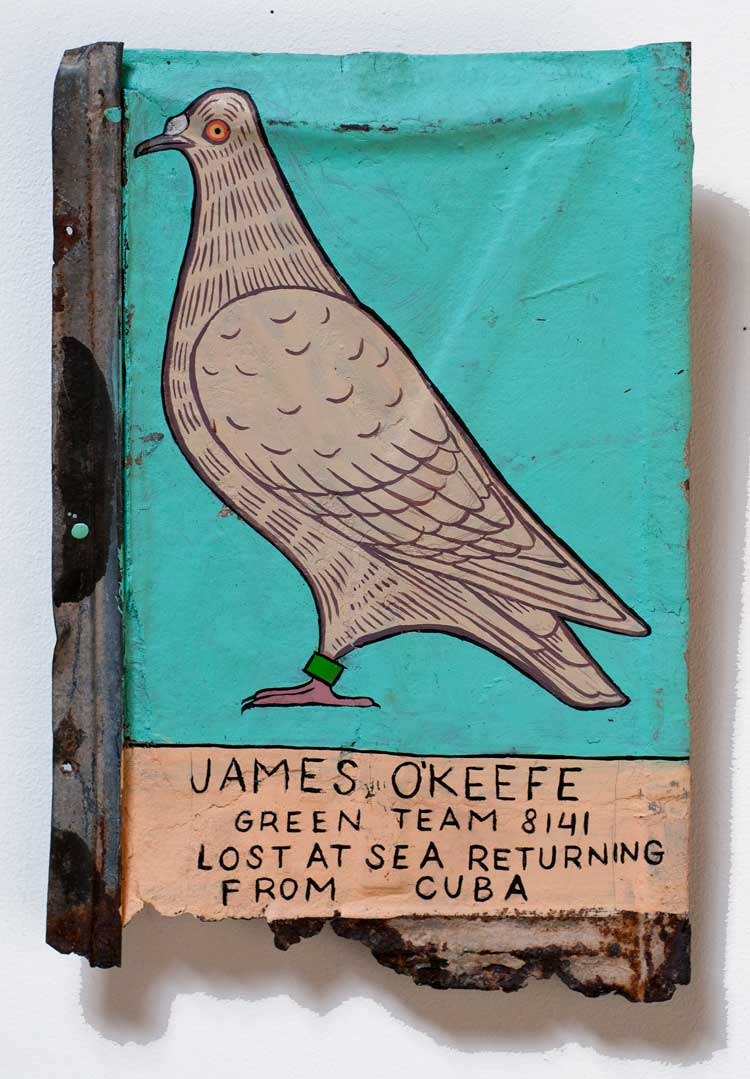

DR: I had 50 pigeons in the project: 25 were trained to fly and smuggle Cuban cigars from Cuba to Key West in Florida and they were all named after famous American smugglers. The other 25 birds were trained to carry small cameras, so I could document the process and prove that I did it. Those were all named after different film-makers who had had trouble with the law.

MP: Such as Roman Polanski. So, you started working with pigeons long before you did your epic performance piece Fly By Night in 2016?

DR: In my early 20s I lived in a pigeon coop. Pigeons have always been involved in my work. Trading with the Enemy was the first major pigeon project, the first notable project, I suppose. And while I was training the pigeons in Cuba, someone, who was working in a bookstore, gave me this second world war manual. It included several chapters about flying pigeons at night. I started thinking about that. Although I didn’t use the manual to train the pigeons to fly from Cuba to Key West, it piqued my interest in flying birds at night. So, I started to think about Fly By Night.

Duke Riley, The Smugglers (James Okeefe). Reclaimed roofing tile and gouache, 35.56 x 22.86 cm. Artwork shown at See You at the Finish Line. Presented by Magnan Metz Gallery, 1 November – 25 January 2014. Photo courtesy of Duke Riley Studio.

MP: How do you train these pigeons?

DR: I spoil them rotten and, as long as I treat them nice, they’re very, very smart, and they love learning new things. People have been training pigeons to fly between Cuba and Key West for hundreds of years. It’s very common in Cuba. During pigeon races, if the wind changes and pigeons get blown off course, they end up in Key West. Training them to fly at night was more difficult. That was a long process, especially training that many birds.

Duke Riley, Fly By Night. Presented by Creative Time, 7 May – 19 June 2016.

MP: For Fly By Night you trained 2,000 pigeons to fly into the New York sky, each bird equipped with a small LED lamp. The flock circled over the harbour at dusk, giving the public an unforgettable show of moving lights. You later repeated the performance in London.

DR: I started in the fall of 2015 and the first New York show opened in mid-May 2016. We had around eight months to train the pigeons.

MP: You did the performance right here, by the river in front of your studio.

DR: It was how I found the studio. I met the guy, who holds the lease on this building. He is a fishmonger, a fish broker, and I worked in the fish business as a kid, and we connected over that and I was looking for a space.

MP: Would you consider New York your home?

DR: New York? Yeah. I mean, I have been here since 1997. The city has changed significantly, in some ways for the worse, but a lot of the issues people have with these changes, you will pretty much find them in every other city around the world. In many of the cities that I visit at least. I spend most of my time between Red Hook and the Navy Yard, that’s my general realm. I live in this sort of weird bubble – sort of stuck in time.

MP: What is your favourite piece in the exhibition?

DR: I don’t have one. I am constantly switching from one medium to the next, so it never gets boring. One day I am working on scrimshaw, next day I am working on valentines, or mosaics, or videos. I switch it up and kind of bounce around.

Riley has to get ready for another meeting. Our hour passed in a heartbeat. His work is so rich and versatile, from dramatic performances to poetic mosaics, to quiet, refined scrimshaw works. I didn’t get to ask him about his drawing A Semi-Subjective Map of the Glorious Gowanus Canal from the Colonial to Post-Industrial Eras (2021). It tells the story of the Brooklyn estuary that was repurposed as an industrial canal in the mid 19th-century, and today is one of the most contaminated bodies of water in the United States. The Gowanus Canal tested positive for gonorrhoea in 2007, and contains benzenes, PCPs and lead. Typically for Riley, he delivers his devastating message in a beautiful work of art. Even the study for the piece, Tidal Fool (2022), which is also exhibited, is breathtaking. Hundreds of curling waves overlap, and each wave lifts a new waste product to the surface, a can of Bud Light, a drink from Shake Shack, a Covid test …

Riley’s exhibition had such an impact on the administrators at the Brooklyn Museum that they changed the cafeteria supplies to minimise single-use plastic, and altered the water fountains to make it easier to refill reusable bottles. And Riley keeps going. His Instagram shows a video of him stepping on a pile of Crocs and other plastic sandals on the beach. The caption reads: “If anyone is working on a biodegradable or kelp-based flip-flop, I’d be happy to do a drawing collaboration ‘cause there sure are a helluva lot of these washing up on the beach.”

• Duke Riley: DEATH TO THE LIVING, Long Live Trash is at the Brooklyn Museum until 23 April 2023.