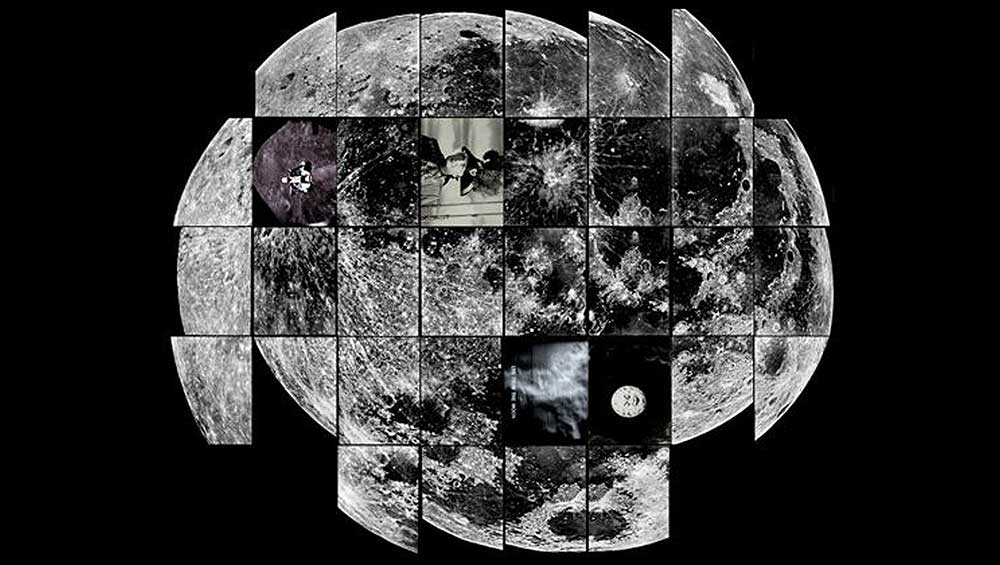

Clea T. Waite, Moonwalk. Experimental film with sound design by Helga Pogatschar, 2010/202.

The National Arts Club, New York

14 December 2021 – 6 January 2022

by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

An informative and timely, but regretfully short-lived, exhibition at the National Arts Club in New York was dedicated to century-old ideas of escaping the seeming chaos of our earthly existence and the exploration of the cosmic universe. Curated by Natalia Kolodzei of the Kolodzei Art Foundation, which is dedicated to collecting art from Russia and the former Soviet Union, the exhibition comprised more than 40 works by 25 artists, most of whom are from this region. The exhibition was the concluding part of a larger project of Cyfest-13, an international festival of media art, which opened at the Made in NY Media Center by the Independent Filmmaker Project in Brooklyn in December 2019, shortly before the Covid-19 pandemic. The festival’s theme marked the 60th anniversary of man’s first flight into the cosmos, and several original photographs of cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin’s first public appearance, at Vnukovo Airport in Moscow, after his flight on 12 April 1961 were on display.

Leonid Lazarev, Moscow. Vnukovo. Yuri Gagarin. April 14, 1961. Black and white photograph, edition 2/10; Kolodzei Art Foundation.

The sense of excitement emanating from these images was almost palpable: a crowd of photographers vying for the best shot of the historic scene; Nikita Khrushchev and other members of the Soviet government paying homage to the man who dared to risk his life to explore the unknown; Gagarin himself, smiling widely and visibly relaxed, marching towards them, ignoring his untied shoelace flapping about. Leonid Lazarev (1937-2021), who took these pictures, recalled that when Gagarin emerged from the plane: “His appearance, his relaxed demeanour and his achievements created a magical attraction.”1 Lazarev’s photographs convey this sense of a unique moment and the enthusiasm of all those witnessing it.

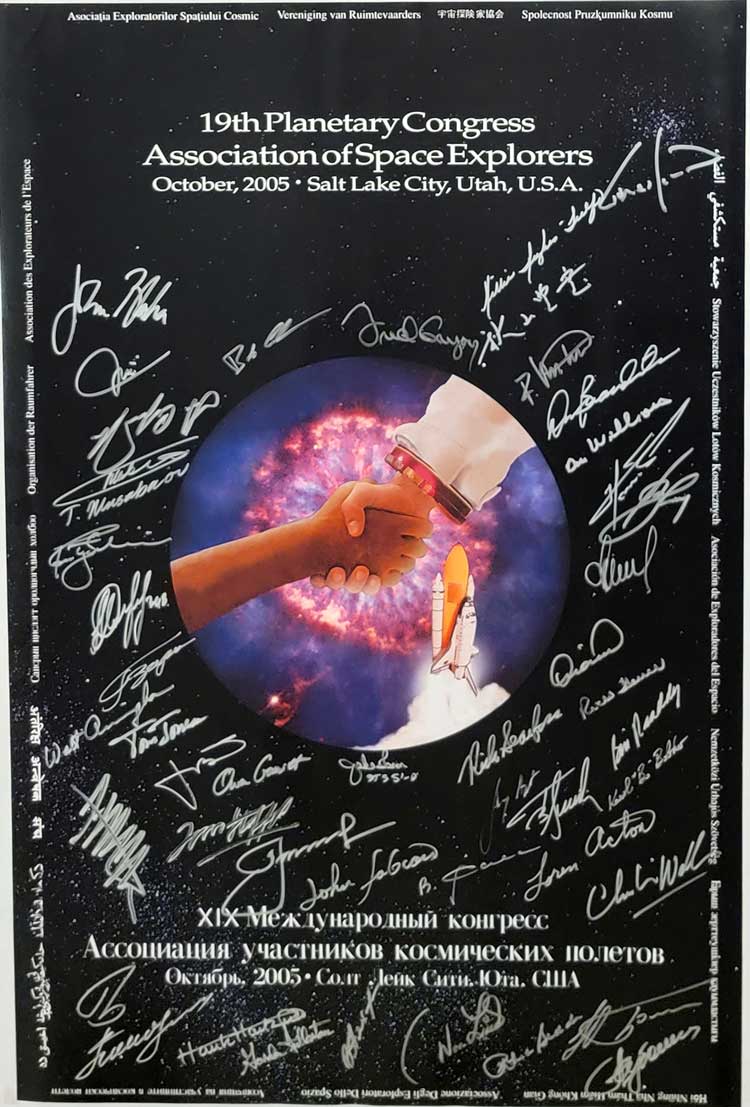

Poster for the XIX International Congress of the Association of Space Explorers, 2005.

Apart from Lazarev’s photographs, the documentary section of the exhibition also contains two works of art that made a journey into space and an Association of Space Explorers poster from its XIX International Congress, signed by a cohort of astronauts and cosmonauts. These images refer to journeys or events that involved travel into space and serve as the factual core of the exhibition. The rest of the show is devoted to artistic interpretations of the ideas of such travel, as well as explorations of more dystopian visions of our Earth plagued by natural and man-made disasters. The majority of the works belong to the Kolodzei Art Foundation, and date from the mid-60s to the early 2000s.

As Kolodzei explained in her article published in a special issue of the journal Leonardo dedicated to Cyfest-13, the ideas of the possibility of life in the cosmos and cosmic travel were articulated by Russian philosophers and religious thinkers as early as the middle of the 19th century. Their progenitor was Nikolai Fedorov (1829-1903), who believed that, in a technological age, it was possible to achieve human immortality and travel beyond the confines of the Earth.2 These ideas of “Russian cosmism” were inspired by scientific thinkers such as Konstantin Tsiolkovsky (1857-1935), who made calculations and draughted designs for rockets and space stations. Inevitably, they also influenced avant-garde artists and their adherents, Soviet nonconformists whose works are featured in the Kolodzei Foundation collection.

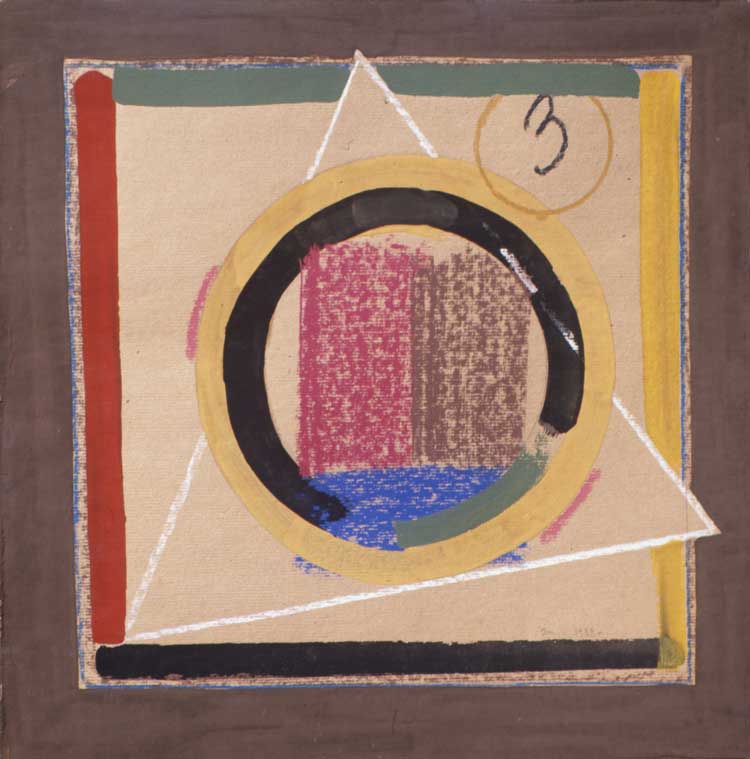

Eduard Steinberg, Composition, 1988. Tempera on cardboard; Kolodzei Art Foundation.

Foremost among these artists was Eduard Steinberg (1937-2012), who was influenced by the ideas of Russian religious thinkers as well as by the art of Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935), whom he admired as a “metaphysical” creator and whose geometric shapes he imbued with mystical and symbolic meaning. The geometry in Steinberg’s compositions reminds one of Malevich’s stark squares, triangles and circles, but Steinberg de-emphasises the materiality of the work’s faktura and gives it an air of a found object and an enigmatic symbol.

Francisco Arana Infante, Spiral #2, 1965. Tempera mixed media on fiberboard.

The central figure of Soviet nonconformism was Francisco Infante-Arana [known as Francisco Infante] (b1943), five of whose works are on display. Infante’s innovative kinetic works, which span the period from the mid-60s to the early 80s, explore the idea of the infinite, which, for him, was closely linked with that of the cosmos. The earliest of his works in the exhibition is Spiral #2 from 1965, which combines traditional and technologically enhanced materials, such as tempera and fibreboard. In it, we see a spiral of blinding light moving sinuously from the bottom to the top of a vertically oriented support. Seemingly abstract, it can also be seen to represent a continuous flow of energy – be it electricity or an imaginary physical substance flowing inside and across the surface of the painting.

Francisco Arana Infante, Artifacts, 1977. From the series The Life of the Triangle. Silver gelatin print. Kolodzei Art Foundation.

Infante’s later works, which he called “artefacts,” were “geometric objects” made by him and staged in nature. Infante and his wife, Nonna Goriunova (b1944), would place these light-reflective or transparent objects into natural settings, photograph them, then disassemble them. The works themselves existed as documentary records of momentary “events”. At first glance, this process resembles the contemporary practices of the avant garde in the United States, in which artists were recording their short-lived performative works by photographing them. However, rather than addressing the themes of female empowerment (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke), entropy (Robert Smithson), or industrial waste (Gordon Matta-Clark), Infante and Goriunova apparently strove to discover a “second reality” hidden in nature with the help of a man-made contraption.3 The artefacts included in the exhibition show a world transformed through human activity, not in a critical and destructive way, but in a productive and nurturing manner. Infante and Goriunova’s nature does not fall apart and disintegrate, but acquires a new, “cosmic” dimension through human intervention.

Clea T. Waite, Moonwalk (excerpt). Experimental film with sound design by Helga Pogatschar, 2010/2021.

The exhibition also features several outstanding contemporary pieces. One of them is Clea T Waite’s film Moonwalk, prominently displayed next to Lazarev’s photographs of Gagarin. Waite, an experimental film-maker and intermedia artist, is known for her interest in exploring the ways in which art and science can intersect and collaborate. She is also interested in creating immersive, embodied experiences. For this exhibition, Waite has done a lot of work to cut and refashion Moonwalk from an earlier film about the moon shown in a planetarium dome. The result is a 12-minute moving collage, presenting a comprehensive poetic story about our centuries-old fascination with the moon. Waite brings together news clips, documentary footage, popular songs, dances and a masterful narration of the ways in which the moon has been perceived and recorded in our imagination. For the artist, the piece conveys the universality of the moon as a symbol of reconciliation, a cosmic place where the space race and military confrontation of the cold war found the most peaceful resolution. Helga Pogatschar’s impressive original musical score imitates the way the moon might sound if it were to move, crack, or make any noise at all.

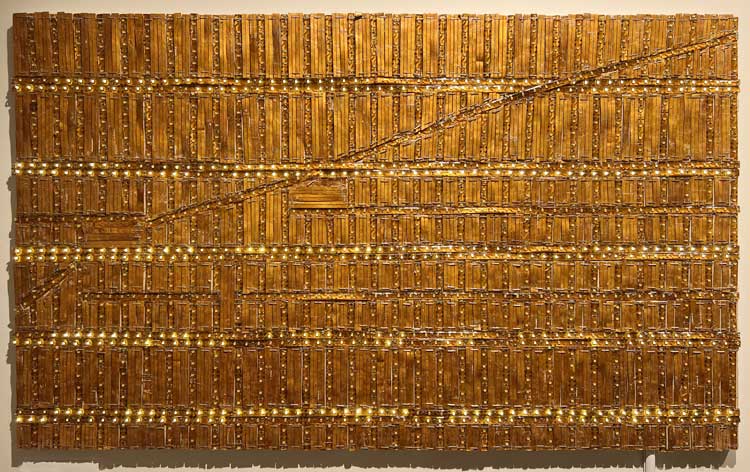

Alexandra Dementieva, New York. Re-lighting, 2021. Mixed media. Object made of recycled LED. Collection of the artist.

Poetic and utopian visions of space exploration presented in the works by Infante and Waite give way to more tempered views of our present and our future. Alexandra Dementieva, a Soviet-born artist who resides in Brussels, showed four new works from the series Re-lighting. Made from recycled LEDs, the works are maps of the four cities close to the artist’s heart – Brussels, New York, Gwangju and Maranola. These are cities where Dementieva lives, exhibits, works or has friends and other personal connections. The pieces are poignant and beautiful not only because, in their subject matter, they remind us of the passage of time and the places we love and leave, but also because the materials themselves – recycled LEDs – convey this sense as well. Dementieva managed to transform the most mundane material into a symbol of life and death. This work makes technological waste look beautiful, giving us a hope for resurrecting our planet.

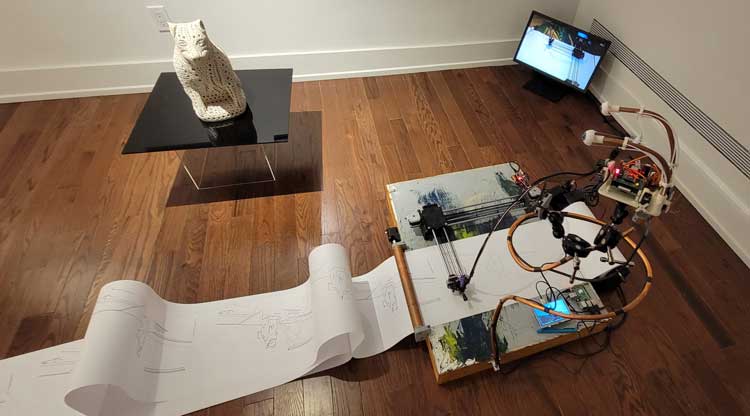

Anna Frants, Homage to Animal Cosmonauts / Astronauts / Space Travelers, from the series Artist’s Union, 2021. Installation.

Anna Frants (b1965), a co-founder of the not-for-profit cultural foundation St Petersburg Arts Project, the Cyland Media Art Lab and Cyberfest, contributed two pieces to the exhibition. In one, the installation Homage to Animal Cosmonauts / Astronauts / Space Travelers, from the series Artist’s Union (2021), a computer was programmed to draw the statue of a dog standing in front of the camera, paying homage to the animal that Soviet scientists decided to launch into space. Frants’ second installation, Peck of Salt (2019), refers to a Russian saying: “You never know anyone till you’ve eaten a bushel of salt with him,” meaning that you must spend a lot of time with a person and go through some hard times together before you can trust him. The work consists of a screen attached to a wall emitting “white noise”, visually and aurally. Below the screen is a constantly growing pile of sea salt. The longer the “white noise” flickers, the more the pile of salt grows. In her commentary for this work, the artist wrote: “Immigrants get accustomed and settle down in their new homeland with the passage of time … The white noise (a vast variety of events and emotions) turns into that very salt – bushel after bushel.” The meaning here is that after the initial confusion about the character of a person, eventually an understanding of his character emerges. People figure things out when given a chance.

Asya Dodina and Slava Polishchuk, Places of Silence. Caumsett II, 2021. Mixed media on canvas. Kolodzei Art Foundation.

Asya Dodina and Slava Polishchuk, a couple who emigrated from Russia after perestroika, presented a more austere and chaotic vision of the state of our world. In the two works on view from the series Places of Silence, the artists created images of emptiness, starkness and devastation. Dodina and Polishchuk’s images have heavy, wrinkled surfaces, coloured in infinite gradations between black and white. They look like post-apocalyptic deserted landscapes that have been devastated by volcanic eruptions, magnetic storms or hurricanes. The tumultuous and rough surface of these works recalls the exaggerated faktura of Russian futurist artists, such as David Burliuk (1882-1967). Burliuk, however, was paying attention to the brute materiality of paint, dragging his painting through the earth in order to build up the thickness of its surface. Dodina and Polishchuk use wet rice paper to achieve the sculpted, three-dimensional effect on the surface of their creations in order to better convey a sense of confusion, destruction and disenchantment.

Dodina and Polishchuk’s landscapes exist on the verge of representation and abstraction. The artists began working on Places of Silence shortly after the start of the pandemic, driving around familiar places in Long Island that habitually teemed with life, and seeing them empty and desolate. The shock of this sudden change was so profound that it inspired this series of paintings, which now contains about 160 paintings and works on paper. The two works on display in Cosmos and Chaos are the most abstracted of the series. Even though they were inspired by specific scenes in Long Island’s Caumsett State Park, they look as if they could have been glimpsed from the window of a space shuttle landing on a far-away planet. In any case, the works convey the sense of anxiety, uneasiness and fear – all that makes us want to escape into a universe governed by reason, where things make sense.

According to the curator, the long run of Cyfest-13, which began before the pandemic, made it possible for her to include works such as Dodina and Polishchuk’s that relate to it. The exhibition then becomes a testimony not only to the historic achievements of the human aspiration to conquer the cosmic universe, but to our ever-present anxiety about our failures to secure a safe and prosperous existence on our planet Earth. Cosmos and chaos remain linked in our imagination, just as they were for the ancient Greeks, who envisioned them as opposite but complementary forces, depending on one another for their existence. It reminds us that we should stand on the ground when we are looking up at the sky.

References

1 Road to the Stars by Natalia Kolodzei. In Leonardo, vol. 54, no. 1, 2021: pages 8-9.

2. Cosmic Inspirations and Explorations by Soviet Nonconformist Artists by Natalia Kolodzei. In Leonardo vol. 54, no. 4, 2021, pages 92-99. On the origins and development of Russian cosmism, also see Russkii Kosmism (Russian Cosmism) by Boris Groys, Ad Marginem Press, Moscow, 2015.

3. Cosmic inspirations, op cit.