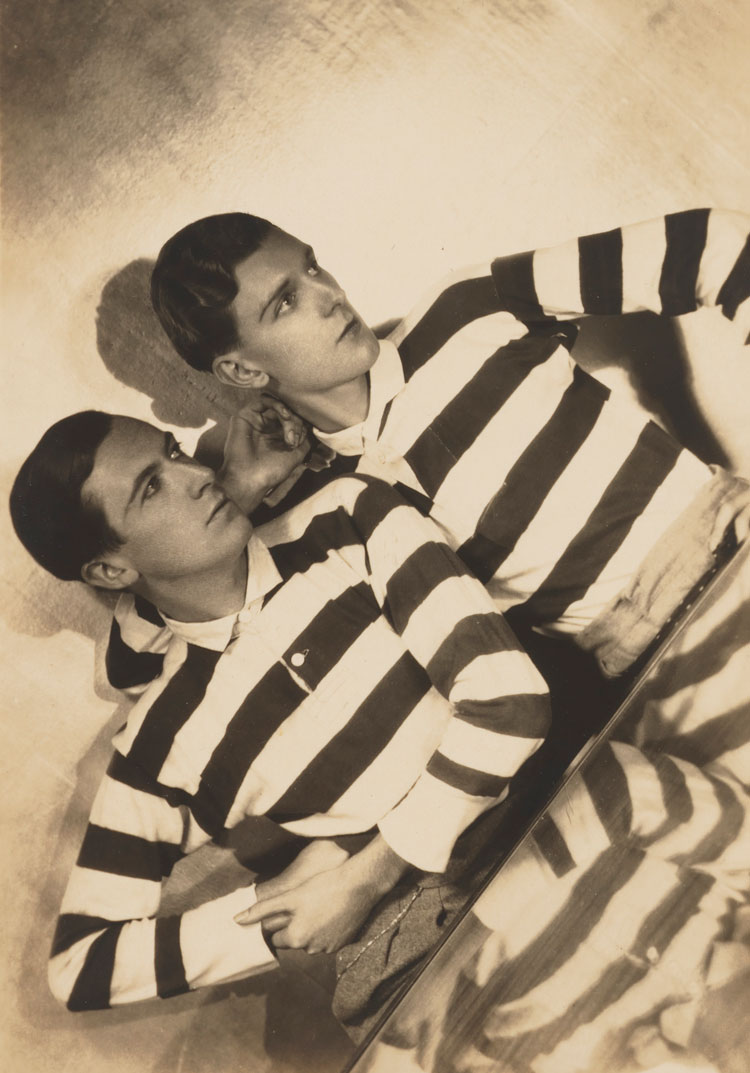

The Bright Young Things at Wilsford by Cecil Beaton, 1927. © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive.

National Portrait Gallery, London

12 March – 7 June 2020

(In line with UK government guidance, the National Portrait Gallery will temporarily close from 18 March 2020 until further notice, to help contain the spread of Covid-19 and ensure the safety and wellbeing of visitors and staff.)

by BETH WILLIAMSON

This exhibition focusing on the early years of Cecil Beaton (1904-80) and his circle in the 1920s and 30s is charming, uplifting and full of fun. Beaton’s friends and acquaintances make vibrant appearances in his photographs, as well as scrapbooks and drawings, in a manner that makes us want to know more about them and their relationships.

Anna May Wong by Cecil Beaton, 1929. © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive.

They were known as the “Bright Young Things”, among them the actress Anna May Wong (1905-61), the artist and stage designer Oliver Messel (1904-78) and the socialite Stephen Tennant (1906-87). The exhibition also includes portraits by other artists and friends of Beaton’s – Rex Whistler (1905-44), Henry Lamb (1883-1960) and Augustus John (1878-1961) – and we begin to sense something of the dialogue between the various sitters and artists. These are a group of young people enjoying life, appreciating themselves and each other for what they are rather than what society might expect.

Nancy and Baba Beaton by Cecil Beaton, 1926. © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive.

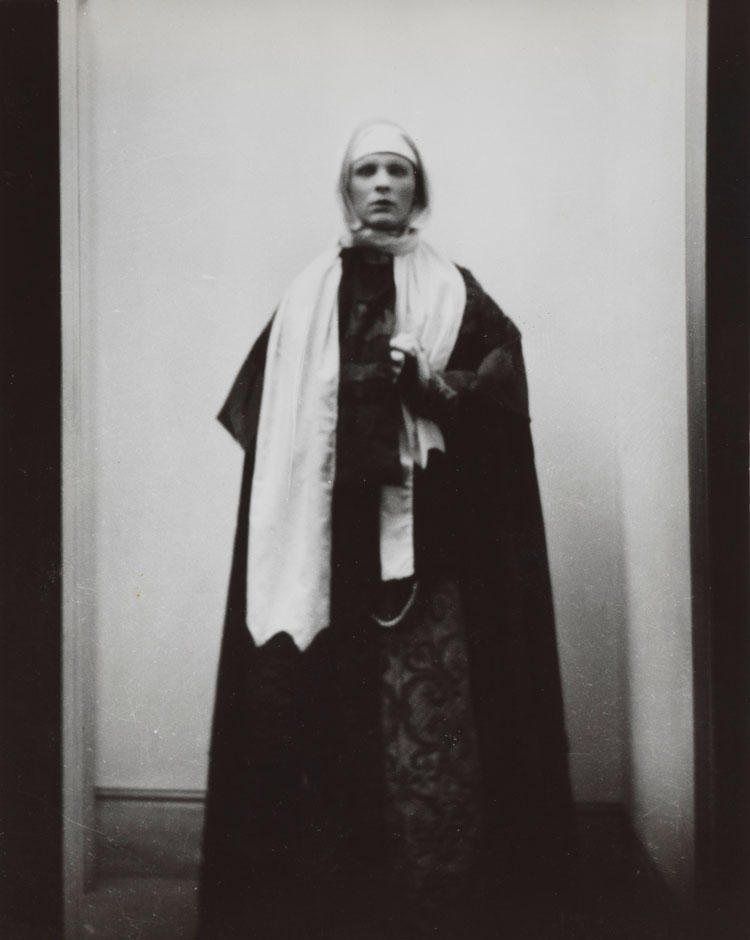

Beaton’s first photographic subjects were members of his family, especially his sisters Nancy (1909-99) and Baba (1912-73). These photographs featured performance and masquerade as Beaton reimagined his sisters in images such as Baba Beaton as the Duchess of Malfi (1926). The influence of other photographers was important, too, as we can see in Nancy and Baba Beaton Reflected in a Piano Lid (1926), a pose Beaton borrowed from photographer Helen Macgregor, one of British Vogue’s chief photographers, whom he had visited in April that year.

Edith Sitwell at Sussex Gardens by Cecil Beaton, 1926. © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive.

By Beaton’s own admission, his time at Cambridge University was a failure academically. However, his activities as an actor and designer for theatrical societies flourished while he was there. When he returned from Cambridge to London in 1925, Beaton worked hard to establish himself among an aristocratic and adventurous group of patrons. Among those patrons were the poet Edith Sitwell (1887-1964), her brother, Osbert Sitwell (1892-1969), and Lady Hazel Lavery (1880-1935), wife of the painter Sir John Lavery (1856-1941).

Most of the photographs seen in this exhibition were taken by Beaton on a Kodak A3 folding camera that he was given in 1916 on his 12th birthday. He used it almost exclusively up to and including his first years at Vogue, where he was under contract from 1926. It is always a joy to see an artist’s tools and materials and so thrilling to see Beaton’s camera in this exhibition. Screened close to this artefact of Beaton’s photography is another – a home movie, or rather extracts from a home movie, made in 1928. For three minutes and 13 seconds, Beaton and friends perform and frolic at the Buckinghamshire home of Lady Cynthia Mosley (1898-1933), known as “Cimmie”.

Cecil Beaton and Stephen Tennant by Maurice Beck and Helen Macgregor, 1927. National Portrait Gallery, London.

Many of the Bright Young Things appeared in Beaton’s first book, The Book of Beauty (1930). Two figures above all were important to Beaton in the 20s and 30s – Tennant and Rex Whistler. Both of these young men were included in Beaton’s arrangement of The Lancret Affair, at Wilsford Manor in 1927. In what is probably the best-known portrait of the Bright Young Things, they appear in costumes reminiscent of the style of the French rococo artist Nicolas Lancret (1690-1743).

Cecil Beaton by Paul Tanqueray, 1937. National Portrait Gallery, London. © Estate of Paul Tanqueray.

While Beaton transformed the appearance of his sitters, he transformed his own appearance, too, writing: “I don’t want people to know me as I really am, but as I am trying and pretending to be.” He acknowledged the influence on his work of others including Man Ray (1890-1976) and Curtis Moffat (1887-1949). The exhibition includes two stunning portraits of Beaton by Moffat and fellow photographer Olivia Wyndham (1897-1967) that use Moffat’s trademark coloured paper (red and green, in these instances) and textured board.

With strong established friendships and patrons, Beaton’s social circles expanded quickly, bringing him readily into contact with some of the most successful writers, musicians, dancers and actors of the time. A trip to New York in 1928 further earned him the support of American Vogue. His exhibition at London’s Cooling Galleries the previous year had been tremendously successful, all helping to build his reputation not only as a portrait photographer, but also as a social commentator.

George ‘Dadie’ Rylands as the Duchess of Malfi by Cecil Beaton, 1924. © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive.

Moving between London and rural locations, the Bright Young Things used both city and countryside for their social gatherings. When Beaton acquired Ashcombe, his own country home, he was truly a member of the group. His summer party there in 1937, jointly hosted with his close friend Sir Michael Duff, had 300 guests. It took the form of a fête champêtre, a garden party in the style of an 18th-century French court. For Beaton, it was a performance, and he and his guests dressed in costume. The photographs are dazzling.

In 1939, Beaton’s career took a new direction when he received an invitation to photograph Queen Elizabeth. During the second world war he became a photographer for the Ministry of Information and travelled the world in his role. Over the course of his career, Beaton won three Oscars and in 1968 was the first living photographer to have a retrospective in any British national museum. In 1972, he was knighted.

Edward Le Bas as Mrs Vulpy in The Watched Pot by Cecil Beaton, 1924. © The Cecil Beaton Studio Archive.

Beaton’s rather serious career from 1939 onwards came in the wake of the fun and frippery of the Bright Young Things years remembered in this exhibition, which is beautifully and thoughtfully designed. The swags and flourishes of architectural features built in to the schema are entirely appropriate and the gold, silver, burgundy and green colour themes in different rooms and spaces are perfect. The Bright Young Things would surely feel entirely at home here.