Antonio Calderara. Senza titolo, 1951. Watercolour on paper, 12 x 15 cm (4 3/4 x 5 7/8 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Lisson Gallery, London

6 July – 20 August 2022

by TOM DENMAN

Lisson Gallery’s exhibition of the works of the Italian postwar painter Antonio Calderara (1903-78) seeks to chart the artist’s drawn-out, and not always consistent, progression from figuration to abstraction, by spotlighting examples of the figurative precursors to the pared-down geometric compositions for which Calderara is better known. In 1934, with his wife, Carmela, and baby daughter, Gabriella, Calderara moved from Milan to the shores of Lake Orta in the Piedmont region of northern Italy, soon settling in the village of Vacciago. As such, his artistic development is framed by his home life – marked by the tragedy of his daughter’s death at the age of 11, in 1944 – and fondness for the Piedmontese landscape, both of which constitute his main subjects. More than a formalist trajectory, the exhibition is interesting for the clues it contains to the intimacy and vulnerability strongly felt even in Calderara’s purest abstractions. If Calderara’s figurative base eventually dissolved, this did not diminish any of his work’s emotional attachment to it.

Antonio Calderara. Senza Titolo, 1958. Oil on wood, 23.5 x 30 cm (9 1/4 x 11 3/4 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

One is first struck by the tiny scale of each work (apart from the framed sequence of watercolours, not one of them exceeds 30cm in breadth). One the one hand, the scale contrasts with the sense of limitlessness pervading his later landscapes and abstractions, and yet such limitlessness is evoked by a diminishment to nothingness – increasing minimalism, the dissolution of form into colour and “light” – in tune with the works’ material insubstantiality. This metaphysical paradox (a general facet of minimalism that is especially pronounced here) governs the way many of the works disappear into formlessness while also taking form. A boat on the horizon in Senza Titolo (1958) keeps the image on the side of figuration, but what if it sailed beyond the threshold?

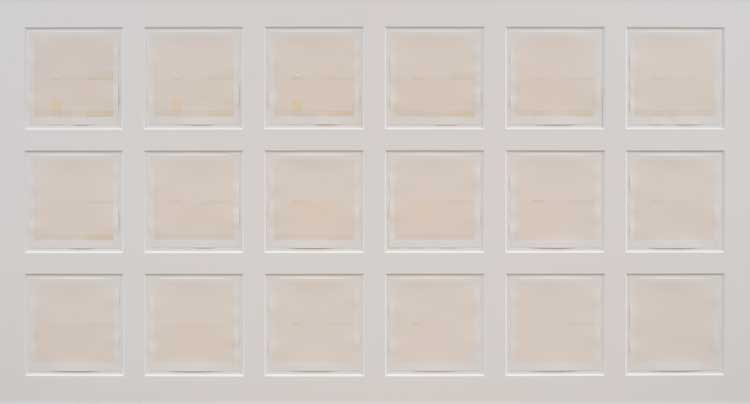

Antonio Calderara. Storie del lago d'Orta, 1976. Watercolour on paper, Framed: 74.5 x 134.5 x 3.5 cm (29 3/8 x 53 x 1 3/8 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

In the sheet in the bottom right corner of Storie del Lago d’Orta (1976) – a sequence of watercolours further contemplating the abstract potential of the horizon – is a blank square, nothing, but it could equally be light, the “source of everything”. Combined with the works’ diminutive scale (and with them being widely spread on the gallery’s walls), this doubleness creates suspense, which heightens our attention. The eye is encouraged to break reality down to its formal and material components; that is, to do the work of abstraction.

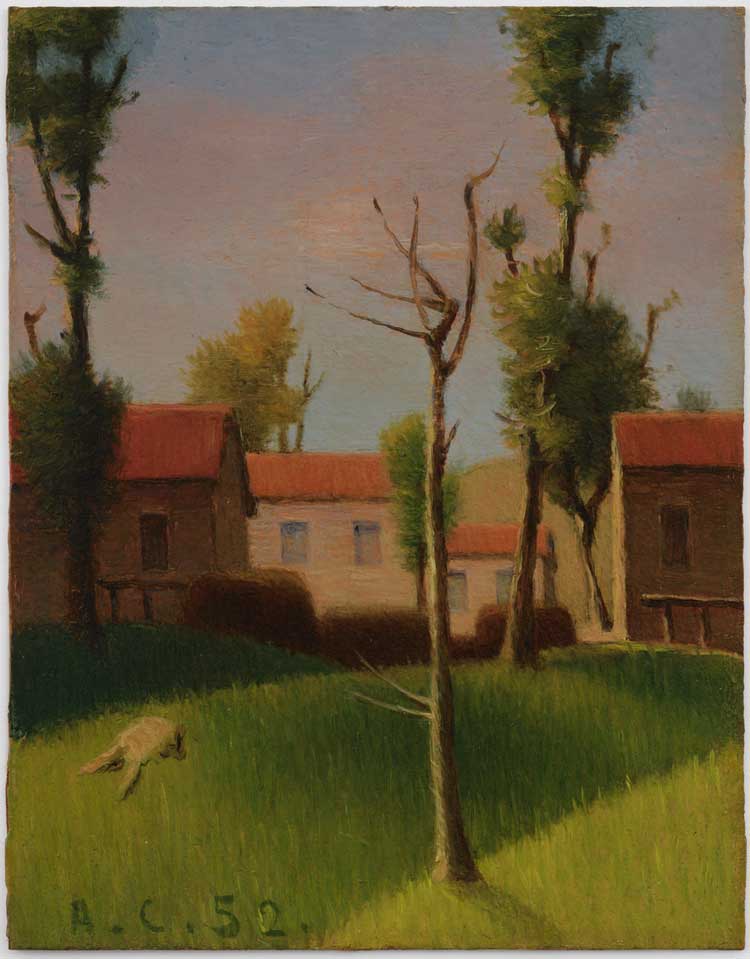

Antonio Calderara. Al Mottarone, 1952. Oil on board, 18.2 x 14.1 cm (7 1/8 x 5 1/2 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

In the earlier oil paintings, we become acquainted with the painter as he battles with the question of what painting is. There is conflict in his layering and almost obsessive overworking of brushstrokes in these works, resonating somewhat with the ghoulish-looking trees in the foregrounds of Il lago d’Orta (1949) and Al Mottarone (1952). And what is that animal in the bottom left corner of the latter work, literally leaping into formlessness?

Antonio Calderara. Natura morta, 1950. Oil on board, 12 x 17 cm (4 3/4 x 6 3/4 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

In the Giorgio Morandi-esque Natura Morta (1950), Calderara explores the contingency of depiction; the subjects struggle to hold on to their identity, the paint spinning them into an agglomeration of non-objective forms.

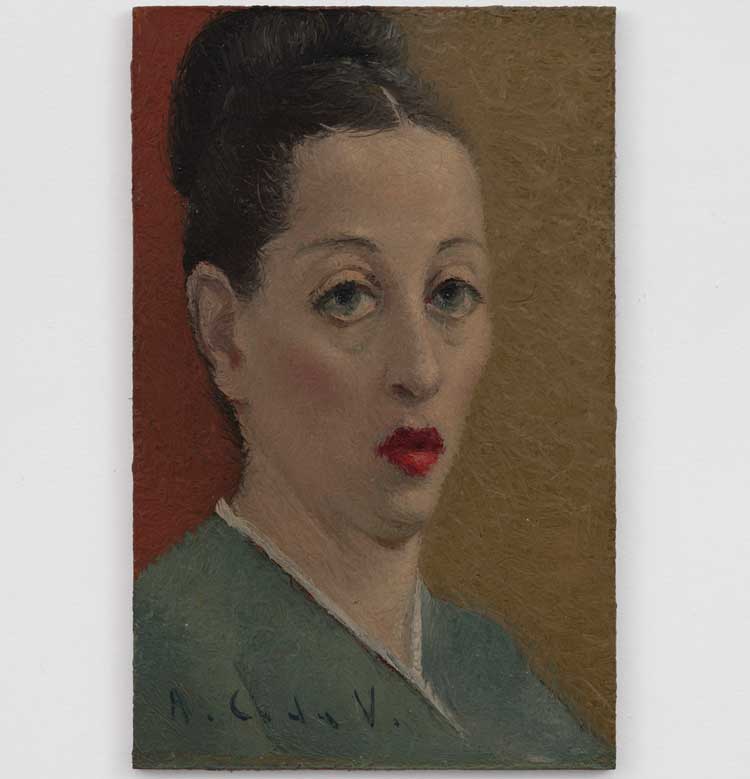

Antonio Calderara. Testa di donna, 1948. Oil on board, 17 x 10.8 cm (6 3/4 x 4 1/4 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Such conflict is especially affecting in the 1948 portrait of his wife (Testa di Donna). Here, Carmela herself seems to be an agent in the painterly struggle, as if her dismissive expression – or, more accurately, the artist’s perception of it – were unsettling any fluid relation between form and mimesis.

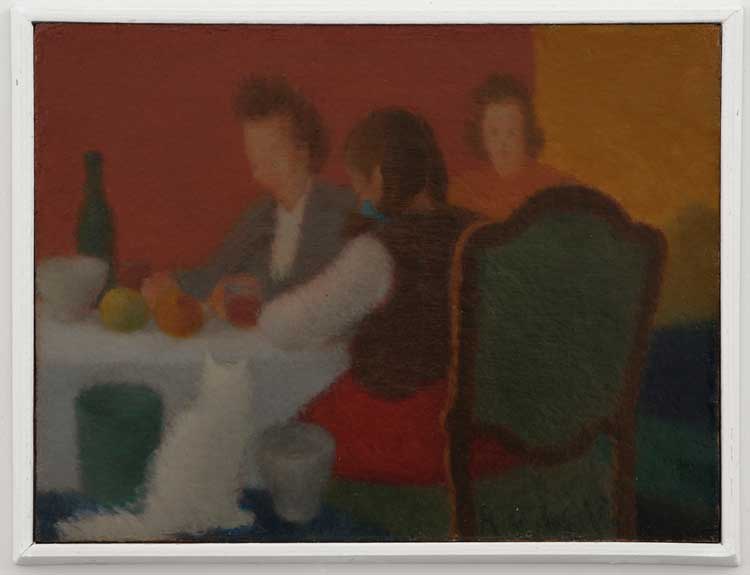

Antonio Calderara. Senza titolo, c1950. Oil on board, 15 x 20 cm (5 7/8 x 7 7/8 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Senza Titolo (c1950) is yet more moving. The brushwork is quieter, as befitting its melancholic and ethereal subject. The girl with her back to us is his daughter, already dead six years, who sits opposite Carmela, while a family friend (identified as Anna Maria Azzoni, who was also their secretary) sits in the background. Even without knowledge of the daughter’s death, there is pathos in this scene, evoked by the artist’s distance from it. This is partly social distance, delineated by the gender divide (especially given the period) and the witty alignment of the artist-viewer’s gaze with the cat’s; and a compositional one, brought about mainly by the figures’ absorption. But it is also temporal, about memory and remembrance, about daydreaming and fantasy, the blurring of contours resonating with the conjuring and fading of images in the mind. Intentionally or otherwise, the thick glaze of varnish on the surface (unique in this show) animates this poignant separation, at once sealing the moment, the memory, and acknowledging its inaccessibility.

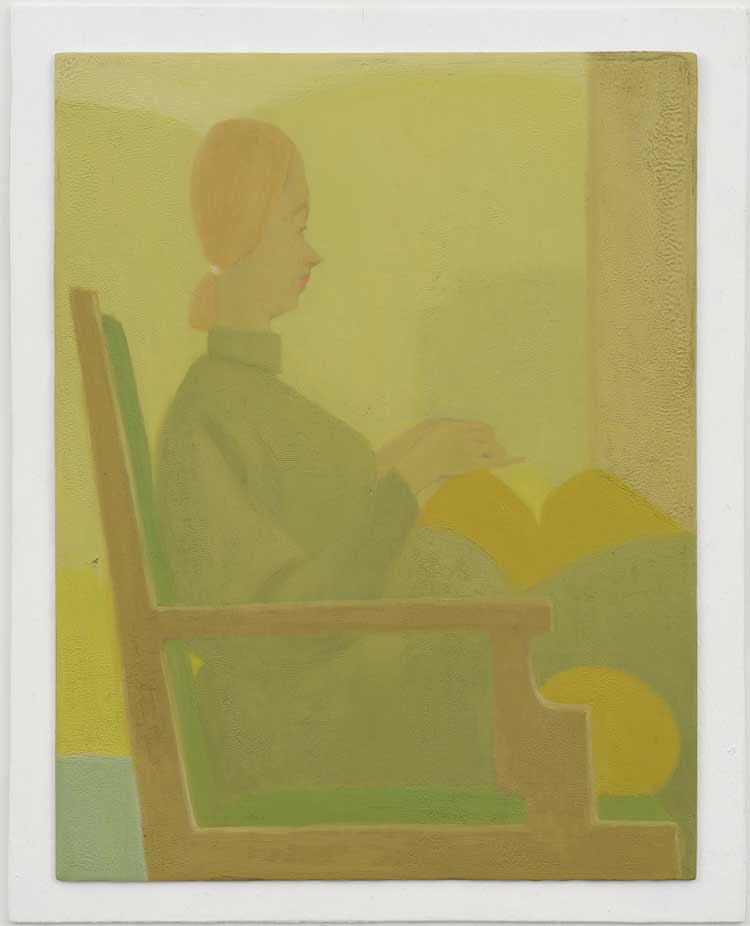

Antonio Calderara. Maternità, 1953. Oil on board, 18.1 x 14.1 cm (7 1/8 x 5 1/2 in). © Estate of Antonio Calderara. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Emotional memory threads through Calderara’s formal experiments. Maternità (1953), which calls to mind Georges Seurat, depicts his wife pregnant with their daughter – almost a decade after Gabriella’s death. Why did he choose such a poignantly heartfelt subject in what might ultimately be a study in geometric composition? Carmela’s green bump is part of a configuration of imbricated curves, as is the yellow fabric she appears to be knitting – something for the future (and past) baby? Knowledge of the artist’s biography enhances a pathos that is already there: in the stillness, the melancholy hues; a pregnant woman on the brink, not of giving life, but of becoming engulfed in form, which is at once an emotional buffer and imbued with uncanny nostalgia. Il Lago d’Orta (c1967) includes a handwritten note beneath the image indicating that it is a study of a work executed 10 years previously. Consisting of overlapping right-angled shapes in blue wash, the work is almost completely abstract. Yet, by giving us the title, the inscription not only indicates its figurative base, but brings us into contact with the artist – we are with him looking at the lake, and remembering looking at the lake.

There is palpable sense of release in his works from the early 1950s onwards, as the oil paintings become flatter and more diffuse, reflecting his experiments with watercolour. If the more laboured oil paintings leading up to this point evoke conflict, here Calderara has found resolution, harmonising materiality with the dissolution of subject matter. In Riva Valdobbia (1957) and Senza Titolo (1958), the subjects yield to the forms they become in paint, culminating in Proporzioni Rettangolari in Verticali (1959-60). The latter presents itself as an abstraction consisting of four rectangles of varying shades of white and very faint blue, colour and form following figuration by gradually dissolving into light. But it is difficult to see this work without remembering the boat and promontory in Senza Titolo (1958) and whatever we might see in Il Llago d’Orta (c1967) in the previous room, both of which are chromatically similar. Again, the artist’s presence is palpable, and not just in relation to other works. The rectangles do not quite meet each other, leaving a visible ridge of paint between them and a fraction inward from the edge of the board. The fluctuating edges maintain the sense of the shoreline, while their imperfection metonymically signals the artist’s vulnerability.

The history of abstraction typically narrates a formal evolution in which the appearance of real-life phenomena serves as the originary basis of the new form. The archetype is Piet Mondrian, whose impressionistic depictions of striated branch formations allegedly metamorphosed into his now-iconic grids. Calderara’s admiration of Mondrian evinced in a poem that he dedicated to him. However, the younger painter departed from Mondrian by disobeying both the stricture of expunging individuality and locality, and the Greenbergian teleology according to which pure abstraction was the height of modernism. The centrality of emotional memory in Calderara’s work, and his tendency to revise and revisit, mean that his story resists such teleological framing. Take Storie del Lago d’Orta (1976), one of his last abstractions that still takes the lake as its premise. At a glance, it could be mistaken for a linear sequence charting the breakdown of form into nothingness or light. But the “histories” of the title are plural. A single sequence cannot be read, and there seems to be an unfathomable leap between the “final” squares and the blank one, as if the artist were aware of an inevitable ending – and it cannot be ignored that he died two years later – but unable to fully determine how to reach it.