Museu D’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Barcelona

7 April – 25 September 2017

by HARRIET THORPE

Essentially, Akram Zaatari’s artistic practice takes the form of a photographic archive. This archive is at once his medium and his subject – theoretical and physical, subjective and objective, a work in progress and a final product. Zaatari, born in Sidon, Lebanon in 1966, founded the archive The Arab Image Foundation, in 1997 in Beirut, with fellow artists Fouad Elkoury, Walid Raad and Samer Mohdad. It is a non-profit organisation that aims to preserve and understand photography from the Middle East, North Africa and the Arab diaspora. The archive of 600,000 photographs, collected from the mid 19th century onwards, capture a period when western values of modernisation began to permeate society in the Middle East.

Blurring the lines between photography, film, archiving, curating, theory and art, Zaatari began working with the archive, collecting photographs, researching photographers, compiling series of photographs, responding to images, exploring photographers through film, and abstractly using the photographs as objects in themselves. This artistic experimentation consequently revealed alternative histories to those captured, such as that of image-making and photography as practice or how identity and self-representation have developed. His work challenges what we might read from a photograph.

Curated by Hiuwai Chu and Bartomeu Marí at Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Against Photography – An Annotated History of the Arab Image Foundation tells the story of the AIF from the beginning, by way of a timeline, and presents an edit of Zaatari’s work over the past 20 years. It is an “annotated history” because Zaatari plays the role of a conscious and critical editor. Working with the archive, he adds side notes, pulls threads together, and reframes the photographs in new ways, joining the dots across decades.

In the series A Photographer’s Shadow (2017), Zaatari groups 28 framed works that have the photographer’s shadow cast across the image. The abstract grouping stretches across the mid-20th century when cameras became more available and people began to experiment – the shadow series shows both novice practitioners operating cameras and photographers experimenting with abstract notions of portraiture.

In the series The Vehicle (2017), Zaatari groups images of Arab families pictured with cars in the desert. Scans of the backs of the photographs are like postcards, scrawled with handwriting and revealing personal histories. One photograph, of three sisters posing with a car, says on the back: “Not always on a camel, also on the BMW.” In another, titled Outing to Becharreh, North Lebanon, 1932, a family is posing piled on the bonnet of a car. As with the shadow portraits, Zaatari is more interested in how people represent themselves through photography than in the subject matter. He worked on a preceding series, The Vehicle: Picturing Moments of Transition in a Modernising Society (1999), which informed this more recent one, because he was interested in examining mobility, leisure and class through the photographs. Perhaps even more revealing are the works in the series The Construction of Class (2017), which show portraits of upper-class families on holiday in Cairo, in which lower-class workers appear to disappear towards the edges of the photographs – holding the tethers of camels, with which the tourists pose, their faces darkened through contrast and their bodies merging with those of the camels.

While some photographs are taken by unknowns, other photographers were sought out by Zaatari for the collection. In the Vehicles series, a photograph of four men standing in the Syrian desert beside a car with a bundle of suitcases tied to its roof was taken by Jibrail Jabbur (1900-91), a photographer and professor of Arabic literature and semitic studies at the American University of Beirut. Jabbur authored the seminal book The Bedouins and the Desert: Aspects of Nomadic Life in the Arab East, originally published in Arabic and then published in English in 1995, in which he ordered his investigation around four subjects: the desert, the camel, the tent and the Bedouin. Zaatari is particularly interested in Jabbur because his photographs document domestic and societal culture in Syria and across the Middle East. Interestingly, we also see Jabbur’s shadow cast across the Syrian desert in the series A Photographer’s Shadow.

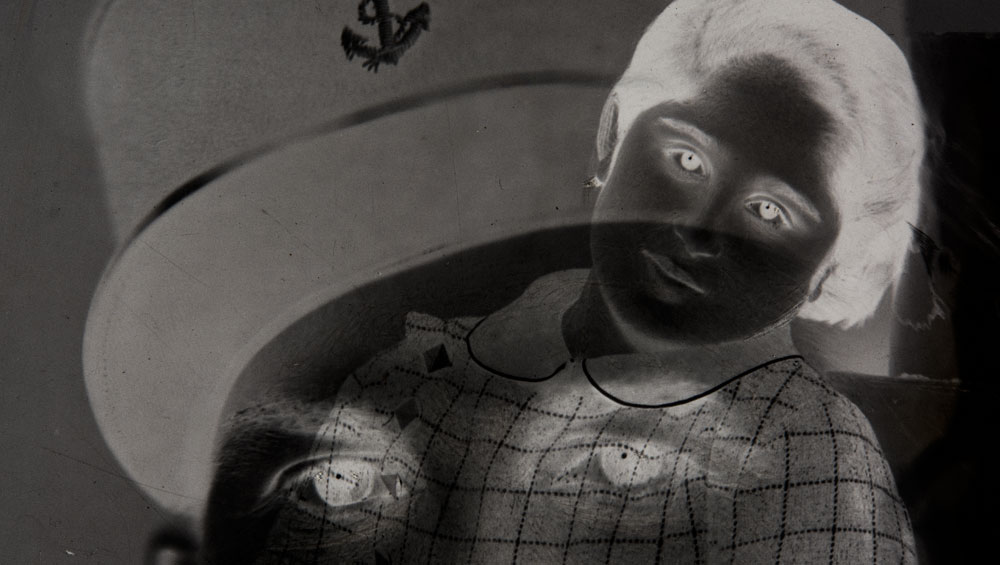

Another person Zaatari is interested in is Van Leo (1921-2002), an Armenian-Egyptian photographer whose family fled from Armenia during the genocide, to Cairo where Van Leo would later set up his own photography studio after becoming enthralled by the cinematic images coming out of Hollywood. Using strong lighting to create a high-contrast black-and-white effect, he began by photographing actors from the opera for free to build his reputation, and then photographed wealthy families, foreign residents and Egyptian celebrities such as Omar Sharif and Loula Sedki, capturing the aspirational glamour of Cairo’s artistic elite. He is also known for a series of 400 self-portraits he took of himself between the ages of 20 and 40 disguised as different characters, from a second world war pilot to a Saudi sheikh, to Jesus, as well as various female characters.

Van Leo captured a time in Cairo when gender and identity were being questioned and explored. Alongside a documentary-style interview that Zaatari conducted with Van Leo in 2001, a series of photographs showing an Egyptian woman gradually stripping off her clothes one by one is displayed. This is a commission that was paid for by the woman herself.

Zaatari responds with his own series, Van Leo’s Footnotes (2017), in which he makes three diptychs with Van Leo’s photographs of the actors Dalidaand Rushdy Abaza, and an unknown Italian woman. Zaatari paints blocks of colour fading from dark to light on to the black-and-white photographs as a gesture to Van Leo’s artistry. Even well after colour photography became widely used, Van Leo remained committed to traditional lighting and developing techniques.

In 1999, Zaatari met photographer Hashem el Madani, who was born in 1928 in Lebanon, and began his longest running project with the AIF, collecting Madani’s photographs taken from the early 1950s at his studio, Studio Shehrazade in Saida, Lebanon. Yet Zaatari also worked on building an intimate portrait of Madani himself. In both of the works Objects of Study/Studio Shehrazade – Reception Space (2006) and Twenty-Eight Nights and a Poem (2010), Zaatari instead turned the lens back on Madani, photographing his studio in the first work and objects from it in the second, capturing his practice through his tools and his working environment. In the film Nota Final (2014), Zaatari documents an encounter he had with Madani. The two men sit in a darkened room at a computer talking and watching the screen together. There is something casual and familiar about the scene and it feels as if Zaatari is trying to capture something very human, the layer of life that is often lost when a photograph is displayed in a gallery or printed on paper.

In the work On Photography, People and Modern Times (2010), Zaatari compiles filmed interviews with photographers and shows them on an old television, which is an object in the film. Set in the AIF, the film shows an archive assistant placing photographs from the collection on a white table, revealing them, exchanging them and replacing them with new ones, to tell a story as the photographers speak. There is beauty in the organisation of the objects and the heaviness of the analogue film camera that sits nearby on the table. Zaatari reveals the aesthetic of the archive itself, displaying its materiality like a documentary of a documentary.

The exhibition uncovers constant reminders of the physicality of the archive. An empty facsimile slide box and empty folders show traces of the archive’s nature as a physical carrier of information. The work Archive Fever (2017) even illustrates the 2008 reorganisation of the archive, when a new methodology was put in place to save space, through a display of the new formation of archive boxes. The physicality of the photographs is similarly explored in the series Sculpting with Time (2017), where details from negative reels of film are projected and lit up across the walls. The crops, which Zaatari reshot with his camera, frame details of faces, textures, glances and forms. The works open up the possibility of a photograph being a completely abstract form and also reiterate ideas of reframing and requestioning images.

Zaatari’s alternative methods of working with photography and film reveal new narratives that attempt to broaden and intensify our understanding of history. He proves that an archive is not necessarily chronological, or straightforward, and engages his combination of visual and analytical skills as an artist, in collaboration with the exhibition format, to provide a complex and revealing way of understanding the modern social history of the Middle East.