reviewed by BETH WILLIAMSON

This book is the first of its kind in any language to explore the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement in the context of the international Arts and Crafts movements. The Young Poland movement arose in the 1890s, a time when, astonishingly, Poland had been an invisible country for almost 100 years. From the late 18th-century, Poland was subject to a series of successive partitions dividing it between Russia, Austria and Prussia, so that the country disappeared from the map of Europe for 123 years. In the wake of failed military uprisings, culture became a way of preserving Poland’s threatened national identity. Young Poland encompassed a blossoming of the applied arts and the rebirth of crafts, taking inspiration from nature, history, rustic traditions and craftsmanship to express patriotic sentiments and values.

Zofia Kogut. Shawl, made in the Kraków Workshops, 1921. Batik-decorated silk, 216 x 47.5 cm. Image courtesy National Museum in Kraków. © NMK Photographic Department.

This generously illustrated publication sets out the history of the artists, designers and craftspeople whose work came to define Young Poland. More than 250 illustrations include ceramics, furniture, textiles, wood carvings, stained glass and children’s toys as well as public, domestic and church interiors. Included for the reader’s delight are images of bespoke nursery furniture, an embroidered chasuble, ceramic stove tiles, a “Devil” Christmas tree decoration, handbound books, Polish kilims, bookcases, armchairs, paintings and much more.

Bronisława Rychter-Janowska. Avenue of Birches, 1910. Wall hanging. Woollen cloth, pieced work and appliqué, 97 × 145.5 cm. Image courtesy National Museum in Kraków. © NMK Photographic Department.

The book’s authors argue that the period of Young Poland shared essential similarities with the British Arts and Crafts movement, and that it was the Arts and Crafts philosophy that fired the movement’s patriotic ideology and the national endeavour to regain Polish independence. Although Young Poland’s visual aesthetic was self-sufficient, searching, as it did, for a characteristic national style and identity, it was also diverse as it looked to the rest of Europe including Britain, especially the Pre-Raphaelites and the ideals of John Ruskin (1819-1900) and William Morris (1834-96). The reception of Ruskin’s work in Poland began in the 1890s and was initially based on translations of writings about him by Robert de La Sizeranne (1866-1932). Indeed, there was a cultural exchange between Poland and Britain when, in 1848, the members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood included a Pole, Tadeusz Kościuszko (1746-1817), on their list of inspirational heroes, what they called “Immortals”.

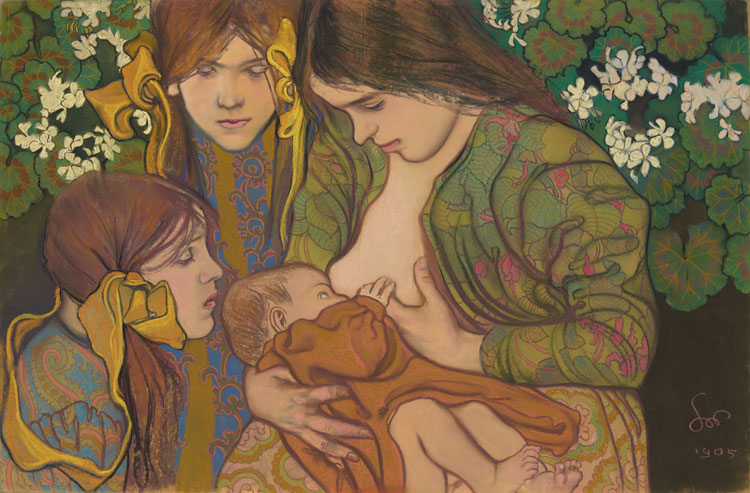

Stanisław Wyspiański. Maternity, 1905. Pastel on paper, 58.8 × 91 cm. Image courtesy National Museum in Kraków, © NMK Photographic Department.

Stanisław Wyspiański (1869-1907), a key figure of the Young Poland movement, was Morris’s counterpart. Nature and history were key subjects for both men and they shared a belief in the equal status of fine and decorative arts. Like Morris, Wyspiański was a polymath and both men created a huge variety of work, including respected writings, and advocated for the preservation of historic buildings. Wyspiański also helped to establish the Polish Applied Arts Society in 1901, the equivalent of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society in Britain.

The Zakopane style of architecture and interior decoration, drawing on the building techniques and traditions of local people who lived at the foot of the Tatra mountains, arose from Young Poland. Stanisław Witkiewicz, the founder of Zakopane style, considered these traditions to be the essence of “Polishness”. He apparently developed the style before becoming aware of Ruskin and Morris. Witkiewicz corresponded with Ruskin in 1899, sending him photographs of Zakopane style schemes.

Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska. Illustration for a Fairy Tale, 1914. Watercolour on paper, 23 × 35 cm. Image courtesy Museum of Literature, Warsaw.

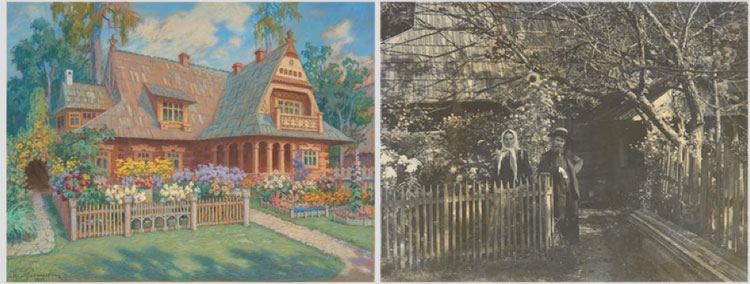

Less studied artists of the Young Poland aesthetic are also examined in this book, in particular Karol Kłosowski (1882-1971) and Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska (1891-1945), whose distinctive roles, we are told, have often been overlooked. Kłosowski was a sculptor and woodcarver, painter, textile designer and paper cutter. His Silent Villa (Willa Cicha) is a Zakopane style Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art, that typifies the Arts and Crafts philosophy. Kłosowski first moved to the village of Zakopane in 1896 and married Katarzyna Sobczak (1866-1915) in 1907, moving into his wife’s house, so Sobczakówka became the Silent Villa (Willa Cicha) where he lived until his death in 1971. The wooden house was developed bit by bit into a “commodious family seat” in the Zakopane style.

Left: Karol Kłosowski’s drawing of the Silent Villa dated 1941, showing the house and the garden after all extensions and alterations, 59 × 72 cm. Right: Photograph of Karol Kłosowski and his wife Katarzyna in front of the Silent Villa, taken presumably between 1907 and 1915. Private Collection. By Descent from the Artist © NMK Photographic Department.

Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska was known for her poetry and watercolour paintings that included fantastical elements inspired by Polish folk traditions. This is the first time these aspects of her work have been examined. Her fellow poet Beata Obertyńska (1898-1980) recalled this of Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska’s painting: “Herbs, seeds, grasses , leaves and flowers – supernaturally enlarged and incredibly accurate in line and mood, yet transmuted by her in her own way into enchanted thickets, seabeds, haze or smoke, often swarming with creatures, half-human, half-insect, fantastically drawn into the tangle of this cabalistic botanical labyrinth.” In this way, the natural became supernatural in her paintings.

Willa Koliba, designed by Stanisław Witkiewicz, 1892–3, with west extension wing designed by Tadeusz Prauss, 1901. Image courtesy Tatra Museum, Willa Koliba © Dawid Moździerz.

The sheer range of work to emerge from the Young Poland movement is staggering – ceramics, furniture, textiles, wood carvings, stained glass, toys, interiors and, of course, paintings. Even within these different modes of making, there is great diversity of style. If we consider Young Poland painting, the subject matter came from metaphors of the nation, spirituality and religion, history and nature. I have already mentioned Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska’s supernatural subjects. Vlastimil Hofman (1881-1970) referenced Renaissance composition and iconography, stylised for his native Poland, such as in Madonna with a Starling (1909), in which the Madonna is dressed in folk costume. Jan Rembowski (1879-1923), on the other hand, painted Highlanders Marching (1909-10), showing Highlander men, women and children marching at dawn, looking ahead, a metaphor for Poland’s march towards independence. As part of a painting cycle for the Dłuski sanatorium in Zakopane, Rembowski’s painting is also a good example of Young Poland’s integration of the fine and decorative arts. Leon Wyczółkowski (1852-1936) painted Giewont (1898), a mountain whose silhouette appears as a sleeping man, a symbol of national existence for Poland in the same way that Fujiyama is a symbol for Japan.

National and international, arts and crafts, decorative and functional, serious and playful, Young Poland is a fascinating movement, whose artists deserve more attention. It has to be hoped that this book and the forthcoming exhibition at the William Morris Gallery in London will garner greater interest and draw in the attention they deserve. The book is well-researched and beautifully illustrated. With such diverse work within a single movement, the illustrations take on particular importance. It provides a helpful overview of the movement, its key people, places and ideas. Then, a series of seven studies of objects and crafts practices provides more in-depth perspectives. This book can certainly stand on its own, but the intellectual and aesthetic journeys it maps out mean that the desire to see the objects themselves is overwhelming, so I look forward to the exhibition.

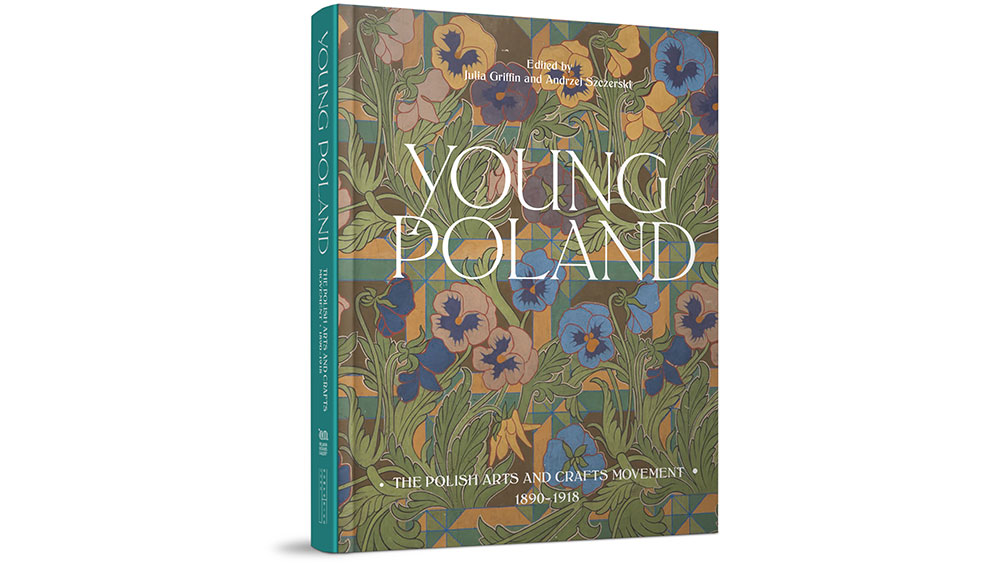

• Young Poland: The Polish Arts and Crafts Movement, 1890-1918, edited by Julia Griffin and Andrzej Szczerski, is published by Lund Humphries, price £40.

• The related exhibition, Young Poland, will be on view at the William Morris Gallery, London, in autumn 2021.