Thomas Becket: Murder and the Making of a Saint (Installation view). British Museum

British Museum, London

20 May – 22 Aug 2021

by EMILY SPICER

The rise and fall of Thomas Becket is a tale of friendship and betrayal, ambition and murder, a medieval saga that echoes down the centuries like footsteps ringing out along the gothic cloisters of Canterbury Cathedral. An exhibition at the British Museum revels in the twists and turns of this gory tale, which famously sees the eponymous priest slain by four bloodthirsty knights, his brains spilled in the name of vengeance.

Becket was born in Cheapside, London, a stone’s throw from St Pauls Cathedral, to parents who had emigrated from northern France. He was considered dashing and intelligent; he was also quick-witted and brimming with ambition. As a young man, he found work as a clerk to the Archbishop of Canterbury and, such was his talent for legal wrangling and diplomatic matters, the archbishop recommended him for the position of Chancellor to the new king, Henry II. Henry took a liking to Becket and the two became close friends.

Detail showing the castration of Eilward of Westoning. Miracle window, Canterbury Cathedral, early 1200s. © The Chapter, Canterbury Cathedral

This exhibition sets the scene brilliantly, with evocative items from Becket’s London. A pair of cow’s shin bones, worn smooth through use, were, the text explains, strapped to the feet and used as ice skates on the frozen marshes of Moorfields. There are also stone carvings from buildings – entwined beasts biting each other’s tails and toothy depictions of dogs representing breeds we would be unlikely to recognise today.

In addition to making Becket Chancellor, Henry II, in a bid to increase his control over church matters, appointed his friend to the position of Archbishop of Canterbury, the most senior ecclesiastical role in the land. It seemed the perfect solution. Becket, we are told, had led a largely secular life, and would, Henry reasoned, have no qualms about fulfilling the king’s wishes and limiting the church’s power in matters of state. But Becket was no one’s puppet and soon the two were at loggerheads.

There are some truly spectacular manuscripts in this exhibition attesting to Becket’s enthusiasm for his new role. He collected and commissioned religious manuscripts, and a copy of the New Testament, made around 1162, is thought to contain the only surviving contemporary image of the new archbishop. Here he is, dressed in glorious blue robes, his hand raised in a gesture of benediction. At about this time, Becket rejected his chancellorship and stood against the king in matters that saw the state interfering in the realm of the church. Their relationship disintegrated and Becket fled to France for six years.

On his return, in 1170, he excommunicated a number of bishops who had supported the king, which sent Henry into a rage. Four of his loyal knights, on hearing Henry’s outburst, rode to Canterbury to arrest Becket. What happened next is as infamous a part of English history as the Battle of Hastings. When Becket resisted the knights’ attempts to seize him, one of their number sliced off the crown of his head. More blows ensued and eventually the priest’s brains were scattered across the cold flagstones of the cathedral’s altar.

Reliquary casket showing the murder of Thomas Becket. Limoges, France, about 1180-1190. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Becket’s violent murder, which had happened in such a holy place, immediately sent shockwaves through the country and then through Europe. Just three years after his death, he was canonised. A reliquary chest made in Limoges, France (1180-90), depicts the moment the first knight’s sword strikes the archbishop’s head, the slender protagonists rendered in gleaming copper, against a background of blue enamel. The scene above shows Becket’s body as it is lowered into a tomb. To the right, two angels carry his soul to heaven.

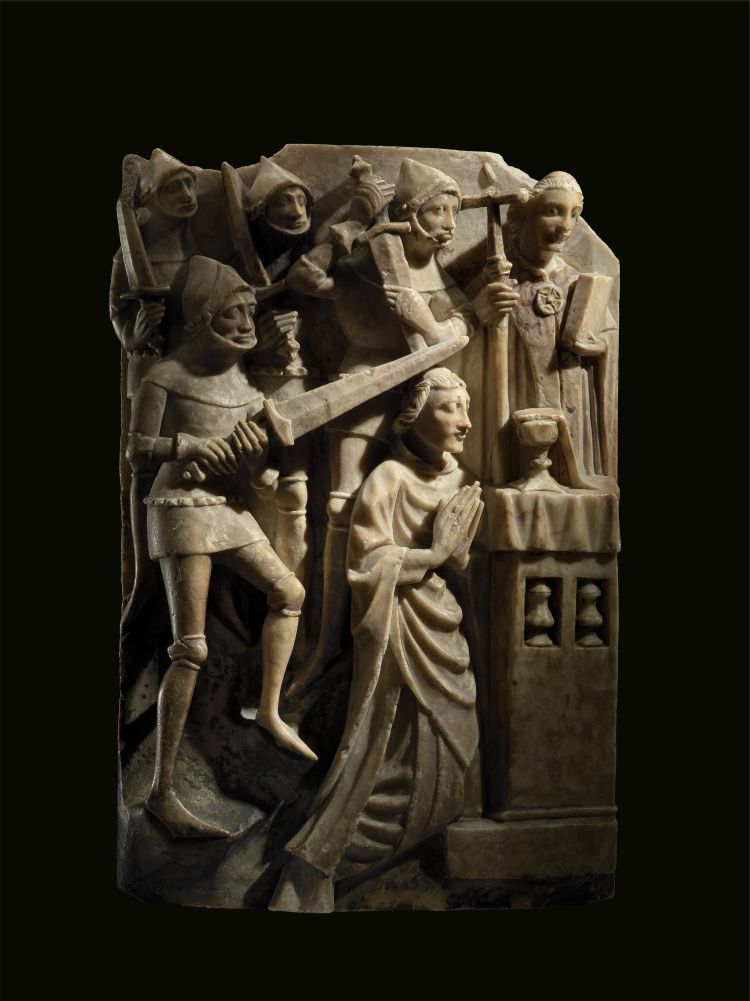

Alabaster panel showing the murder of Thomas Becket. England, around 1425-50. © The Trustees of the British Museum

For a while there were more English churches dedicated to Becket than any other saint. One alabaster relief carving made for a church in the mid-1400s depicts the now familiar scene with enthusiasm. The murderous knights find Becket kneeling at the altar and raise their swords. Edward Grim, a visiting monk, who was injured in the fracas, bears witness to the murder. Perhaps because this frieze was carved 300 years after the event, it lacks the gravity of early renditions, but none of the energy. The cartoony, bug-eyed assassins resemble players in a Shakespearean farce, but their delicately rendered features are full of character and detail. Centuries have passed, but the scene still warrants meticulous attention.

Henri de Flemalle, Reliquary statue of Thomas Becket. Liège, about 1666. © The British Jesuit Province

The cult of Becket grew and Canterbury Cathedral would become a site of pilgrimage to rival Jerusalem and Rome. The pilgrim’s journey (as playfully recounted by Geoffrey Chaucer) would conclude at Becket’s ornate, jewel-encrusted shrine. The shrine has long-since been destroyed, a victim of Henry VIII’s Reformation. But some of the sumptuous stained-glass that decorated the nearby windows have survived. There were originally 12 six-metre tall windows, each depicting miracles linked to Becket after his death. Several sections of these windows are on display here, backlit so we can appreciate their full technicolour glory. One panel tells the story of an unfortunate man who was relieved of his eyes and testicles as a punishment for stealing. Becket appears to the man in a vision and, on waking, he finds that his missing organs have been restored to him.

Skull relic and reliquary of Thomas Becket, 12th century. © British Jesuit Province

While Henry VIII revoked Becket’s sainthood in England – he was, after all, martyred for refusing to accept royal interference in church matters, an issue close to the Tudor king’s heart – he continued to be a popular saint in Europe. As England became a Protestant nation and split from Rome, English Catholics had to be creative about the ways they preserved Becket’s legacy. Many reliquaries were smuggled out of the country, including the last item on display here. Trussed up in a piece of red velvet and sealed within a little brooch-like repository, is a fragment of bone, reportedly a piece of the Archbishop’s skull.

Remarkably, this is the first major exhibition to explore Becket’s life and the cult that grew up after his death. With all its gory details, rich objects and excellent storytelling, this is not just a show for medieval buffs, but for anyone who enjoys intrigue and plot twists. His religious significance may have diminished since Henry VIII’s time, but this exhibition proves that his story has an enduring appeal.