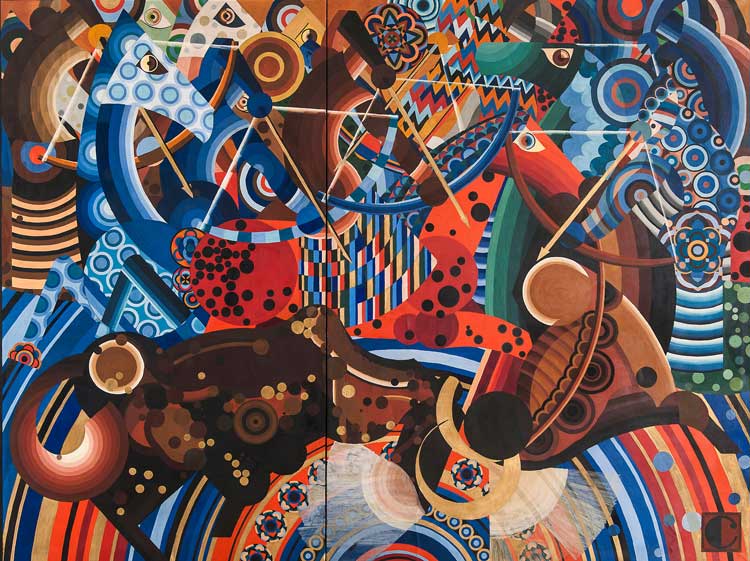

Sascha Wiederhold, Archers, 1928 (detail). Oil on cardboard on canvas, 204 x 240 cm. National Museums in Berlin, National Gallery, acquired in 2021 by the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation. Photo: Galerie Brockstedt © Sebastian Schobbert © legal successor Sascha Wiederhold.

Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin

2 July 2022 – 8 January 2023

by JOE LLOYD

Sascha Wiederhold’s Archers (1928) is a hunting scene like no other. The subject is quite conventional: bowmen on horseback surrounding their target, arrows pointed menacingly down for the kill. But this is where any familiarity ends. The painting is a kaleidoscope of swirling patterns and bright colours, a motley carnival. One horse has a pale blue head covered in target-like roundels in further shades of blue. A saddle is depicted as a patchwork of many-coloured squares. It is difficult to work out what prey the horsemen are shooting towards. The whole pulsates with sound and motion like a futurist canvas, and glimmers like the Orphic cubism of Sonia and Robert Delaunay. But the subject is oddly archaic.

Sascha Wiederhold, Archers, 1928. Oil on cardboard on canvas, 204 x 240 cm. National Museums in Berlin, National Gallery, acquired in 2021 by the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation. Photo: Galerie Brockstedt © Sebastian Schobbert © legal successor Sascha Wiederhold.

Archers was recently acquired by Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie, during the almost decade-long restoration of Mies van der Rohe’s landmark modernist building. When the museum reopened in 2021, it was hung in the foyer. It is the first work visitors see of the Neu Nationalgalerie’s unparalleled permanent collection of German modern art. It received a warm public reception. In light of this success, the museum has now devoted a temporary exhibition to the work of Wiederhold (1904-62), the first comprehensive retrospective. Whoever found the work and made the purchase must be proud indeed.

The phenomenon of the forgotten artist, languishing in subterranean collection stacks across the world until some curator digs them up, has become a constant of today’s culture industry. There is an almost indefinite supply of hidden geniuses to uncover: the number of artists who have remained in favour is minute compared to those who have been lost to the mists of time. Wiederhold is an interesting example because his disappearance from art history was, in part, elective.

Born in Münster and initially educated in Düsseldorf, Wiederhold moved to Berlin in 1924 to study. He was thrown out of the academy, however, after being caught sleeping inside it. Despite this calamity, he quickly found a place in the creative tumult of the Weimar-era capital. Herwarth Walden, the artist, editor and modern art promoter, exhibited him at his Galerie Der Sturm in 1925 and 1927, also showing his works in New York. Parallel to his Berlin career, Wiederhold designed sets for theatres in Magdeburg and Tilsit (now Sovetsk in Kaliningrad). But then, in 1933, the National Socialists took power. In 1937, the year modernist art was declared degenerate, Wiederhold hung up his brush and took a job as a trainee bookseller. He produced no further art, except for some small figure drawings made while he was a prisoner of war in 1946. In 1951, he and his wife opened their own bookshop in Moabit, a working-class area of West Berlin, which he ran until his death.

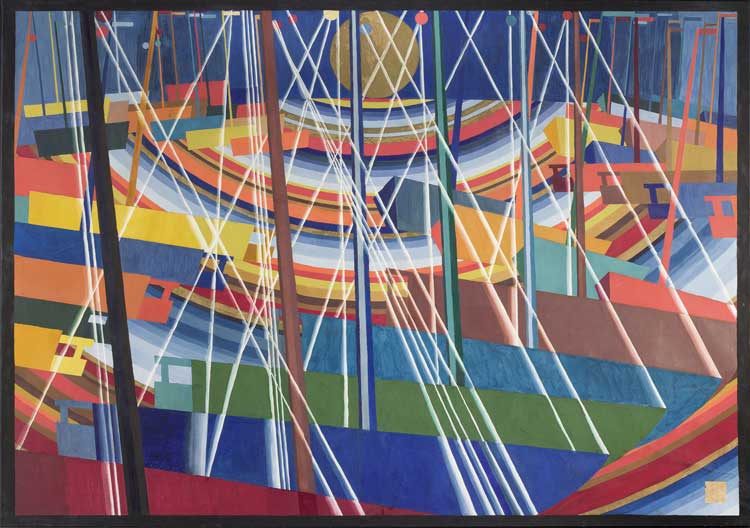

Sascha Wiederhold, Sailboats in the harbour, 1929. Oil, tempera and gold bronze on paper, laid down on canvas, 158 x 219 cm. Silard Isaak Collection, Carl Laszlo estate © legal successor Sascha Wiederd.

Wiederhold was rediscovered in the 1960s by the collector and dealer Carl Laszlo and featured in some small exhibitions in the 1970s, but did not find a significant audience. This seems surprising, given that his work shares remarkable affinities with the psychedelic art of that time. This is especially the case with his few surviving large-format paintings, of which Archers is one. These are exceptional works. Sailboats in the Harbour (1929), which uses oil, tempera and gold bronze on paper, features rows of block colour boats floating on a rippling sunset sea, their masts and rigging crisscrossing into the sky.

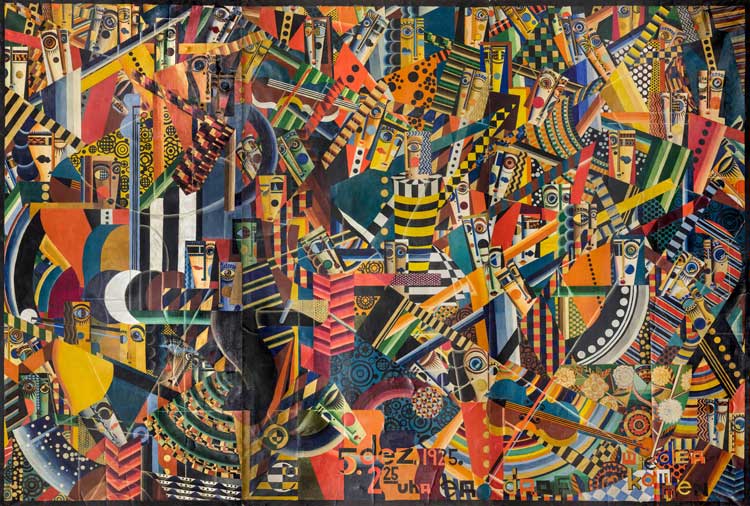

Sascha Wiederhold, Jazz-Symphonie, 1927. Oil, tempera, gold and silver bronze on paper, laid down on canvas, 306 x 456 cm. Silard Isaak Collection, Estate of Carl Laszlo, © Legal successor of Sascha Wiederhold, Photo: Thomas Bruns.

Even better are those works in which he explores music and dance. Jazz Symphony (1927), his largest work, presents a frenzy of musicians and dancers sprawled across a bar. At first, little appears to make sense, other than the strange, Fernand Léger-esque heads of the figures. On closer examination, instruments and parameters of the bar begin to appear. Wiederhold blends figurative and abstract painting elements, as well as decorative elements resembling applied arts, into a swirling cacophony. It is the two-dimensional equivalent of Walter Ruttmann’s film Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, from the same year, giving life to the rhythms of the modern metropol

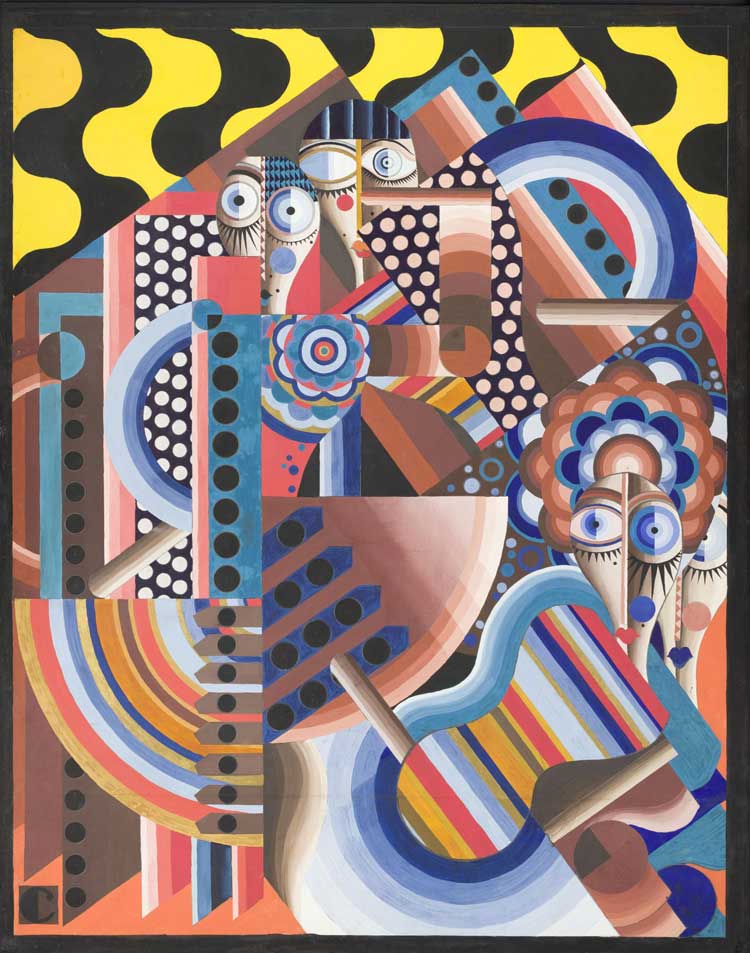

The theme of modern city life carries through to many of Wiederhold’s smaller paintings. In The Kiss on the Hand (1928), the titular amorous act occurs across a grid of rising skyscrapers, more like something from Metropolis than the mid-rise Berlin of the 1920s. The smaller works also highlight the element of the grotesque present in Wiederhold’s bizarre figures. In Dancer (1926), he presents fragments of heads with bulbous eyes, like mutilated fragments of Aardman Animations’ characters.

Sascha Wiederhold, Dancer, 1926. Tempera, gold and silver bronze on paper, laid down on canvas and plywood, 135 x 107 cm. Silard Isaak Collection, Carl Laszlo estate © legal successor Sascha Wiederhold.

Given the evident relish with which Wiederhold captured life in bustling motion, it might be surprising that he had such an affinity with set design, creating empty spaces to be filled by the action of others. Not that his designs are often empty. If his painting seem to pre-empt, in aesthetic terms at least, the psychedelia of the 60s, his set drawings resemble a postmodern beyond the wildest dreams of the Memphis Group. One, for Jack Larric’s Oelrausch, depicts a room covered in Delaunay roundels, another for Gogol’s Marriage, has constructivist swoops and spikes. Both have jagged, converted backgrounds redolent of expressionist cinema. In other sets, Wiederhold conjures shadowy woodlands, grand cafes, oppressive villas, ancient Egyptian palaces and labyrinthine city centres.

Sascha Wiederhold, Stage design for When We Dead Awaken by Henrik Ibsen, 2nd act: In the mountains, for the Stadttheater Tilsit, 1929/1930. Gouache, pencil, gold and silver bronze on paper, 40.6 x 41.3 cm. Silard Isaak Collection, estate of Carl Laszlo © legal successor Sascha Wiederhold.

One display contains eight successive sets for a production of Richard III, which show how Wiederhold intended the design to evolve throughout the scenes of the play, a fascinating study of the variety that can be achieved with a limited number of elements. The same could stand for Wiederhold’s oeuvre as whole, which, all of a piece, is a complete world in itself. After seeing his works in person, it would be difficult to mistake them for the works of anyone else. It is a shame that so little of such a fascinating artist survives. The 12 figure drawings from his brief period in a prisoner of war camp show that his unique style persisted after he had otherwise stopped work. But the remnants exhibited at the Neue Nationalgalerie alone should suffice to ensure Wiederhold’s reputation as a unique, talented chronicler of a society thrusting into modernity.

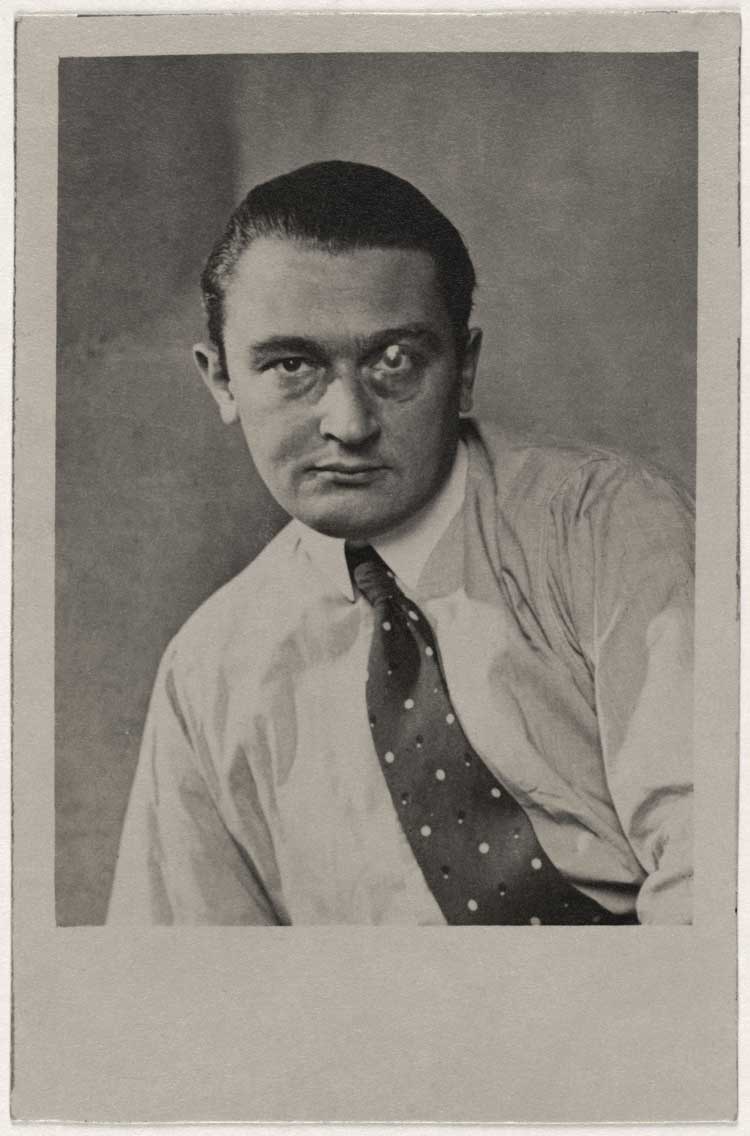

Portrait of Sascha Wiederhold. Repro: Anja Elisabeth Witte.