John Henry Lorimer. Flight of the Swallows, oil on canvas, 1906 (detail). City Art Centre, Edinburgh Museums and Galleries. Photo: Eion Johnston.

City Art Centre, Edinburgh

6 November 2021 – 20 March 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

The work of John Henry Lorimer (1856-1936) is something of an enigma. Highly skilled in his handling of paint, his work has been largely disregarded. Before this exhibition at Edinburgh’s City Art Centre, I have to confess, I had not looked closely at his painting. However, the collection of almost 50 oil paintings, watercolours, sketches and objects displayed here really is fascinating for all sorts of reasons. As the first exhibition of Lorimer’s work since his death in 1936, it is a celebration of his skills and creativity, and the glow of light that seems to emanate from his canvases is at the centre of that celebration.

John Henry Lorimer. Hush, oil on canvas, 1905. Touchstones Rochdale Art Gallery.

Known for his portraits and genre scenes, Lorimer, astonishingly, produced almost 400 oil paintings, including 130 portraits, in his lifetime. Portraits were his mainstay, allowing him to earn a living and spend time on the Edwardian interiors, scenes of family life and light-filled landscapes that he loved. As a young man, he was taught by William McTaggart (1835-1910) and George Paul Chalmers (1833-78) at the Royal Scottish Academy and first exhibited there when he was just 17 years old. He later studied with Carolus-Duran (1837-1917) in Paris for a short time in 1884, and travelled to see galleries across Europe in France, Germany, Holland, Italy and Spain, but always returned home to Scotland.

The Lorimer Family. Photo courtesy of a Private Collection.

The Lorimer family acquired Kellie Castle in Fife, on the east coast of Scotland, in the summer of 1878 and the castle and its grounds feature in many of Lorimer’s paintings as he painted most of them from his turret studio at Kellie. The artist would have been just 21 years old when the lease to the castle was secured that summer and the family set about restoring the castle building.

John Henry Lorimer. Pot Pourri, oil on canvas. Private Collection. Photo: Nick Haynes.

As the exhibition’s co-curator, Charlotte Lorimer, has said: “History tends to remember the rebels. But there is also a place for the quiet craftsmanship of artists such as John Henry.” That quiet craftsmanship is exactly what we can see and experience in this exhibition. John Henry Lorimer was no rebel, but he never associated himself with any artistic group or movement, choosing instead to work alone. His work is presented through the lens of five themes – light, identity, family, femininity and home – themes that make the scenes and sentiments in this exhibition feel familiar and that is thanks to co-curators Charlotte Lorimer and David Patterson. Patterson regards the artist as “technically brilliant” and says: “His elegant interiors and light-filled landscapes will uplift everyone’s spirits during the winter months.” It is true that the uncannily realistic glow of light from Lorimer’s paintings was somewhat heartening on the damp November day I visited. That the paintings are also accompanied by some of the actual objects represented in them, including a chair, a mirror and a cradle, gives a stronger sense of the spaces they occupied.

John Henry Lorimer. Flight of the Swallows, oil on canvas, 1906. City Art Centre, Edinburgh Museums and Galleries. Photo: Eion Johnston.

The exhibition includes the enchanting The Flight of the Swallows (c1906) and Spring Moonlight (1896), both of which have been voted as favourite paintings of Scottish audiences over the years, and you can see why. The Flight of the Swallows has a Peter Pan feel to it and Lorimer’s handling of light in this picture is astonishing. This painting, embodying all five of the curatorial themes, acts as an anchor of sorts for the exhibition and is thought to have been inspired by the departure of Lorimer’s sister Alice from Kellie Castle one autumn. After a summer at Kellie Castle, Alice and her children, like swallows, would have made a September voyage south from Scotland, returning to Guyana where her husband lived and worked. It might be brimming with sentimentality, but it is also overflowing with the artist’s love for his sister and her children. His heartache at their imminent departure from Kellie is palpable in the light and shadow that enfolds their figures in this painting. All dressed in white, the figures almost seem to float, their ethereal presence illuminated by the window, and its reflection.

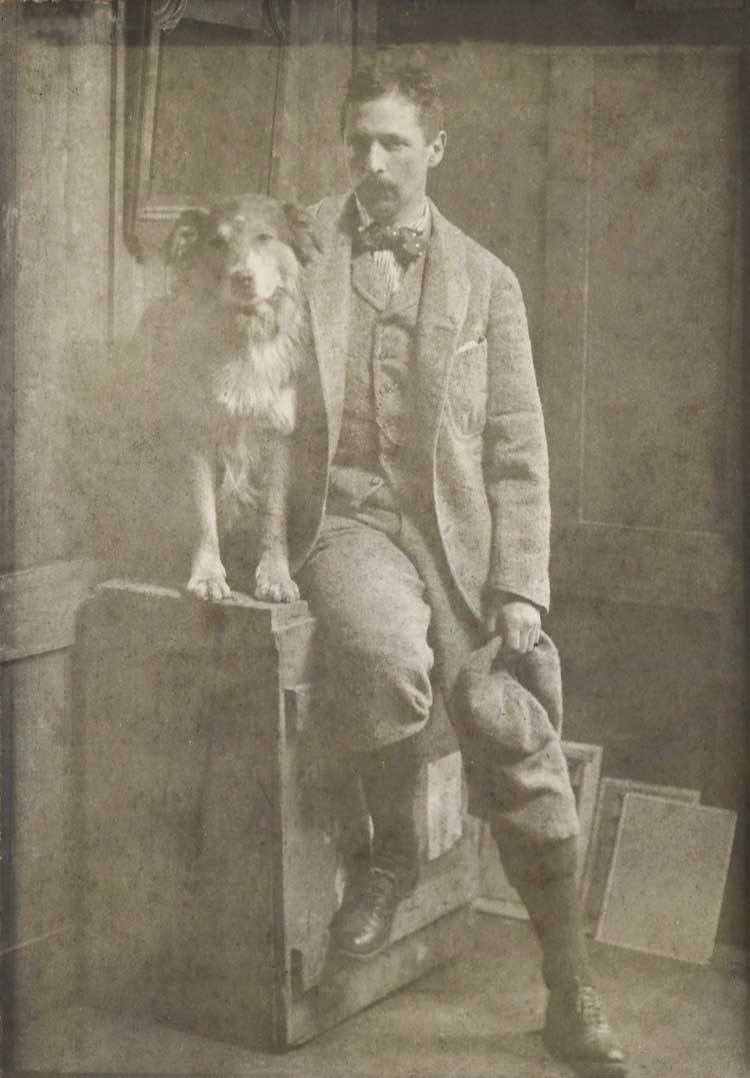

John Henry Lorimer with his dog Burleigh. Photo courtesy of a Private Collection.

Lorimer’s family and friends were important to him and often appeared in his paintings. His older sister Hannah, known as Lorrie, sat for several of his paintings, including a double portrait. The artist’s parents and his youngest brother, Robert, were the focus of Lorimer’s early portraits. Mother’s, sisters and nieces were not the only important female figures in the artist’s life. The family nanny and housemaids were important, too. This importance can be seen in paintings such as Housework’s Aureole (1916). In this painting, a housemaid quietly sweeps an upper landing area with an unseen window casting light on the wall beside her. The radiant glow cast by the window lends a sacred feel to an otherwise secular scene, and housework takes on new importance.

John Henry Lorimer. The Eleventh Hour, oil on canvas, c1894. Private Collection. Photo: Nick Haynes.

Joanna Herbert, born in Guyana and employed by the artist’s sister Alice to care for her six children, visited Scotland from Guyana on numerous occasions and remained part of the family for 40 years. Herbert appears in Lorimer’s Lullaby (1889) and Grandmother’s Birthday (1893). The latter was the first painting by a Scottish artist to be bought by the French government and is usually stored at the Musée D’Orsay in Paris. It hasn’t been displayed since 1989, so it surely deserves to be seen again now.

As much as Lorimer’s paintings cast a warm glowing light over visitors to the exhibition, it is more than a purely visual experience. There is a lively audio guide including dramatised readings of family letters and memoires, as well as a series of 12 original poems inspired by the artist’s paintings and original music too. The short film included in the exhibition also has an interesting story. The script was written by Lorimer’s great niece, Esther Chalmers, about 50 years ago, rediscovered among archival papers, and produced for the exhibition. Still, the paintings remain the stars of the show, and none more so than The Ordination of the Elders in a Scottish Kirk (1891). Six elders gather around the minister and the Bible. By depicting them dressed in black with heads slightly bowed, Lorimer emphasises their reverence for God and the church. The scene is lit from above, reflecting on their heads and shoulders, as if to underline the weight and seriousness of the commitment they are undertaking. For me, this is emblematic of Lorimer’s handling of light, a tool to convey all sorts of messages from the ethereal presence of relatives about to depart, to the innocence of a child, from the vagaries of the weather to the weight of spiritual matters. Light was an essential material for Lorimer, one that is shared generously in this exhibition. The warm glow of sunlight with which he fills his interiors might seem impossible, but it is precisely what visitors will take home with them when they leave this exhibition.