-1000.jpg)

Cathy Wilkes, Untitled (Possil, at Last), 2013. Courtesy of The Artist and The Modern Institute/Toby Webster Ltd., Glasgow. Photo: Cristiano Corte.

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

6 October 2023 – 7 January 2024

by JOE LLOYD

“On December 27, 1989, my mother wrote in her diary: ‘My mother died today.’” So wrote Sophie Calle in Autobiographies (2013), a series of text and photography works. “On March 15, 2006,” she continues, “in turn, I wrote in mine: ‘My mother died today.’ No one will say this about me. The end.” When Calle dies, the chain linking generation to generation will end. Her writing is so terse that the statement could equally read as one of regret or one of vindication. Ending a family line could be a loss or a victory, depending on the circumstance. It could be both at once. Calle’s dry ambivalence only affirms one thing for sure: that she had a family.

Families are everywhere. Almost everyone has one, at least at some point in their life. The type of connections one has to one’s family are almost infinitely varied, ever changing. Nan Goldin had a difficult relationship with hers, especially after her older sister killed herself during the artist’s childhood and her family fell into arguments. But in the 90s, Goldin photographed her mother laughing in a state of ecstatic joy, and her father smiling as he shaved, capturing them with raw sympathy. Chantal Joffe has tracked her family as it grows larger and older. In just a few works, we can see her daughter go from toddler to teen to young adult.

Chantal Joffe. Self-Portrait Combing Esme's Hair, 2009. Oil on canvas, 40.7 x 51 x 2.2 cm. © Chantal Joffe. Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro.

In recent years, the way in which families can be constituted has changed as well. Real Families uses artworks and objects to tell this story. It was curated by the psychologist Susan Golombok, the former director of the University of Cambridge’s vaunted Centre for Family Research. The centre specialises in empirical study rather than theorising, and has tracked how technology and changing social mores have massively expanded what families can be. Science has often led the way. The years between 1978 and 1986 saw the first children born through test-tube, egg donation and embryo donation. Governments have had to adapt to and control these advances and the ramifications they have for family structure.

.jpg)

JJ Levine. Alone Time 19 (from Alone Time series), 2021. Courtesy JJ Levine/ELLEPHANT Gallery.

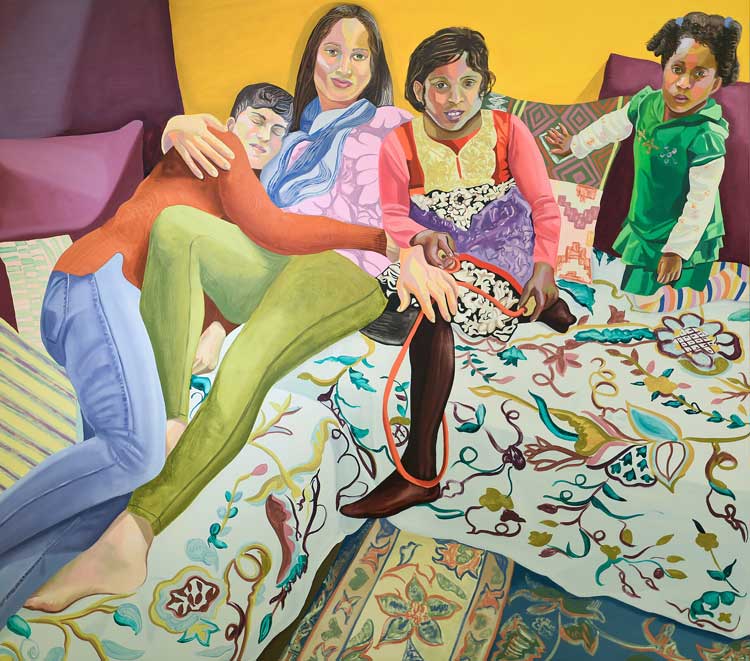

In Britain, there has been a blitz of legislation. Some laws have been progressive. The 1969 Divorce Reform Act made legal separation far easier. The 1987 Family Law Reform Act got rid of illegitimacy. And a trio of acts between 2002 and 2004 allowed adoption by same-gender couples, fully decriminalised homosexuality and allowed civil partnerships. Several of the artworks in the exhibition depict the results of these and similar shifts internationally, such as JJ Levine’s photograph of his family (2018) and Aliza Nisenbaum’s sprightly painting (2018) of a family with lesbian parents embracing on bed.

Aliza Nisenbaum. Susan, Aarti, Keerthana and Princess, Sunday in Brooklyn, 2018. Oil on linen, 145 x 162.6 cm. © Aliza Nisenbaum. Photo courtesy the Artist and Anton Kern Gallery, New York.

Yet there has also been conservative resistance to progress, most notoriously in Section 28 of the UK Local Government Act 1988, which prohibited the “promotion of homosexuality” and smeared same-gender parents as “pretend families”. Tabloid newspapers have rallied against surrogacy, single parents and LGBT couples, both arresting acceptance and echoing the fears of their readers.

Joshua Reynolds. The Braddyll Family, 1789. Oil on canvas, 238.1 x 147.3 cm. Courtesy of The Fitzwilliam Museum.

Real Families begins with a timeline outlining these transformations, along with a 1976 cover of the feminist magazine Spare Rib, campaigning for lesbian parents, and Joshua Reynolds’ portrait of The Braddyll Family (1789). This approach, with old and new placed cheek-by-jowl, continues throughout the exhibition, until a final room, which shines a spotlight on Joffe. Sometimes this works well. Joseph-Marie Vien’s 1749 painting Sarah Presents Hagar to Abraham could depict a biblical predecessor to surrogacy. A particularly well-conceived application of this approach comes in a section dealing with inter-family relationships across time. It includes four portraits of mother and child. The first is Joos van Cleve’s Virgin and Child (c1525-30) from the Fitzwilliam’s collection, a superb northern Renaissance version in which neither Mary nor Jesus has a halo, emphasising their early parallel. The mother smiles with tenderness.

Alice Neel. The De Vegh Twins, 1975. Oil on canvas, 96.5 x 81.3 cm (38 x 32 in). © The Estate of Alice Neel, Courtesy The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner. Photo: Malcom Varon.

Van Cleve is followed by a trio of modern and contemporary works that draw on this topos. Alice Neel’s painting Nancy and Olivia (1967) shows the painter’s daughter clutching her baby for dear life, her face charged with protectiveness and a hint of fear. Catherine Opie’s photograph Self Portrait/Nursing (2004) has the artist strike a defiant note. The word “pervert” can be seen scratched in her chest, a reference to her queer sexuality and the prejudice she and other lesbian mothers have faced. And Lena Cronqvist’s quietly shocking The Madonna (1969) depicts a mother made pale with the sheer exhaustion of rearing a newborn. This sequence speaks to the changing dynamics of families and the shifts in the function of art, from early modern devotion to confessional self-representation.

Zun Lee. Bedtime shenanigans with Carlos Richardson and his daughter, Selah. Harlem, NY, August 2012 (from the project, Father Figure, 2011-15), 2012. Copyright Zun Lee. All rights reserved.

But there are other selections, such as Sassoferrato’s The Holy Family (c1660-85) and, indeed, the Reynolds, that speak more of artistic choices than anything else. Reynolds’ group portrait includes only the family’s son, not their economically less-valued daughters. But there are plenty of examples from the time, including by Reynolds, where this is not the case. An anomaly comes to stand for a norm, for the more radical works of the present day to then shatter. This way of organising an exhibition – where the artworks are in service to already-established narratives – might reveal that it has been convened by researchers rather than curators. As might the prominence of wall text, which turns each work into evidence for pre-defined conclusion. The art is seldom allowed to speak for itself.

Paula Rego. Split, 2017. Pastel on paper on aluminium, 102 x 67 cm. © Ostrich Arts Ltd. Courtesy Ostrich Arts Ltd and Victoria Miro.

There is still much of interest, though. There are some fascinating objects, from a pair of 18th-century ceramic cradles given to newlyweds expressing hope for childbirth to one of the first vacuum desiccators for IVF, a delicate and beautiful thing. There are many inclusions that organically provoke thought, such as Miriam Schaer’s baby clothes (c2012) embroidered with prejudicial phrases women who cannot, or do not want to have, children often encounter. And the exhibition is unafraid to explore the resentments and cruelty that exists in some family units, whether speculatively – as in the case of Paula Rego’s late pastel Split (2017), where a stony-faced boy contemplates literally cutting his family apart with a knife – or demonstrably, as with Tracey Moffatt’s harrowing Scarred for Life (1994) series, where the artist recounts real stories of family-induced trauma in captioned photographs parodying Life magazine. Even as societal conception of a family expands, some things remain the same.