Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. Wild Knots hang over a lane of blue glass bricks. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

Petit Palais, Paris

28 September 2021 – 2 January 2022

by ANA BEATRIZ DUARTE

“Newton’s binomial is as beautiful as the Venus de Milo. The truth is few people notice it,” said the Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa, reuniting maths (and science) and art, long broken apart by the philosophical western tradition that they are separate, even opposite, disciplines. But science and art, says the award-winning mathematician Cédric Villani, “are like two selective mirrors reflecting reality, and ourselves. At times, the reflections converge.”

The Narcissus Theorem, by the French artist Jean-Michel Othoniel, on display until January 2022 at the Petit Palais in Paris, makes a clear statement about this convergence. “The Narcissus Theorem is truly about re-enchantment and the theory of reflections that I developed for nearly 10 years with the help of the Mexican mathematician Aubin Arroyo,” says the artist in an interview with the exhibition’s curator, Christophe Leribault. Indeed, the show is a theory – or rather a “theorem” – about beauty.

Jean-Michel Othoniel, Gold Lotus, 2019. Photo: Claire Dorn / Courtesy of the Artist & Perrotin © Jean-Michel Othoniel / Adagp, Paris, 2021.

Othoniel and Arroyo have been partnering since 2015. The result of this exchange between art and maths is shown in Wild Knots, the main section of The Narcissus Theorem apart from the garden.

In 2011, a friend of Arroyo’s showed him an advertisement for Othoniel’s exhibition at Centre Pompidou. Othoniel’s knots, then called nodes, were already there. He had got to these forms inspired by the French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who built up from a mathematical figure, the Borromean rings, to think about the intersection between the imaginary, the symbolic and the real.

A section from one of Arroyo’s projections of Wild Knots.

The artist and the mathematician finally met in person in 2015. Arroyo was struck by the incredible similarity of Othoniel’s sculptures to the visualisations of maths theories that he was creating. “It was amazing to see the sculptures in vivo. I could see myself reflected in it, not only the beads reflecting one another, as in the computer images I produce. That’s the main difference between our work: my projections are pure and clean, free from external elements.”

Installation view, Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. © Othoniel / ADAGP, Paris 2021. © Photo: Claire Dorn / Courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

Arroyo’s images are visualisations of theorems of so-called wild knots. The poetic name comes from topology, a relatively young branch of mathematics, dating from the end of the 19th century, while its construction comes from another branch of mathematics, dynamical systems, which studies the evolution of phenomena over time. Arroyo explains: “The study of the infinite repetition of some simple rules, such as reflections in a mirror, shows us different representations of infinity. For example: between two parallel mirrors facing each other, we can ‘see’ two different infinities, one on each side. In the case of reflective sphere necklaces, all these infinities draw a curve that is infinitely knotted: and that is, precisely, a wild knot.”

Reflected Narcissus: one can see multiple selves reflected in the sculptures. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

The resemblance to the concept in art history of “mise en abyme” (placed into the abyss) is no coincidence.

There are more than six billion types of catalogued knots – all of which are considered “tame”, that is, they enclose a finite number of intersections. A wild knot, on the other hand, is, so to say, tameless, and thus very difficult to translate into images. For nearly two decades, this has been Arroyo’s endeavour (and, intuitively, also Othoniel’s).

Their partnership has resulted in a book, in 2017, an exhibition at the Centro Cultural Kirchner, in Buenos Aires, in 2019, another one, this year, at the Arsenal Art Contemporain, in Montreal, and, finally, this one at Petit Palais, the first time the wild knots have been displayed in France.

Installation view, Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

The exhibition includes about 30 shapes in shimmering coloured glass spheres created by Othonial based on Arroyo’s studies — all in the low-lit ambience that has been named the Grotto of Narcissus. Some hang from the ceiling at different heights over a lane of blue mirrored bricks. There, the visitor can investigate multiple reflections along a string of pearls, on the bricks and on other knots. Another set, in contrast, is placed on pedestals, where the spheres create a sacred aura reinforced by the shadows reflected on the ceiling, generated by spotlights placed on the floor.

Paintings in black ink resemble the glass spheres just in front of them, but might also be another tribute to flowers, just like La Rose du Louvre, his artwork commissioned in 2019 by the most-visited museum in France.

A set of objects produced during the pandemic lockdowns hangs on the walls, contrasting with the “river” of wild knots. Precious Stonewalls is made up of blocks of regular glass bricks intersected by light, projecting deformed, coloured shadows on the white wall: a mix of minimalism forms and baroque light.

.jpg)

Agora (2019), in The Grotto of Narcissus: a place to hide from the outside world. In the background, Precious Stonewall (2021). Installation view, Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

Bricks, not spheres, still in glass, serve as building blocks for Agora, a cave that visitors can enter. Though the name, coming from the Greek name for a place of assembly, might imply an invitation to speak, most only sit in contemplation.

Indeed, Othoniel may be switching his geometric form of preference. Bricks are front and centre in this show. Blue River, a monumental installation of 1,000 light-blue glass bricks made by Indian craftsmen, covers the steps of the impressive art nouveau entrance of the museum, creating the sensation of a cascade.

.jpg)

Blue River (2021), an in-situ installation for the Petit Palais, an art nouveau building designed for the Universal Exhibition of 1900. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

This is the first instance of a dialogue this in situ exhibition establishes with the architecture and history of Petit Palais (“small palace” in French), built for the Universal Exhibition of 1900 by architect Charles Girault. Other site-specific examples are found in the palace’s garden. There, golden necklaces and rings hang on trees or float over the garden’s three basins, in the form of lotus flowers, described by the French media as like something out of a fairytale.

Installation view, Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. © Othoniel / ADAGP, Paris 2021. © Photo: Claire Dorn / Courtesy the artist and Perrotin.

Although the yellow pieces may remind the visitor of the legend of Narcissus, who fell in love with his own beauty reflected in water and was turned into a flower on his death, the myth gains a more powerful, less literal interpretation with the silver-pearl knots positioned along the half-circle colonnade enclosing the mosaic floor and painted-ceiling of the peristyle of the Petit Palais.

The multiple-layer reflections of a Wild Knot on the top of a mirrored pedestal. Installation view, Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

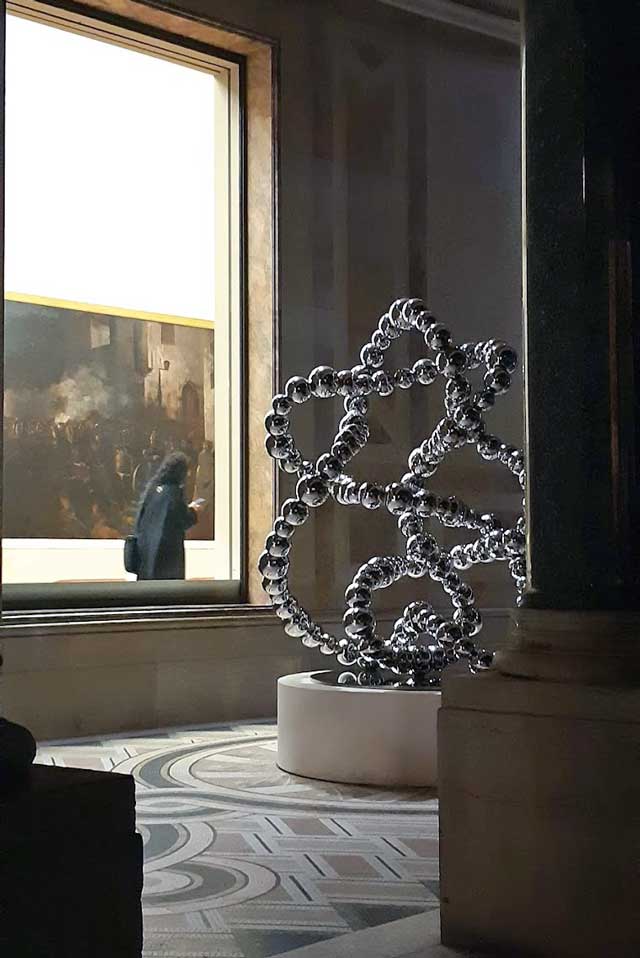

This time, Othoniel chose to use stainless steel, again on mirrored pedestals. The colour is gone and the reflections in contrast are even clearer. On each pearl, the visitors can see themselves, the vegetation and the fin-de-siècle architecture. Placed by the windows, the pearls can even reflect the Courbets and Dorés from inside. An infinite number of infinities are then generated. And they keep changing, depending not only on the viewer’s angle, but also on the amount of daylight and the position of the artificial lights around them. Voilà their metamorphosis – another high point of The Narcissus Theorem. Once again, we are back to the knots, here called mirrored knots. Indeed, the fact that Othoniel has opted for stainless steel might reflect, so to say, his encounter with Arroyo’s mathematical samples, which are exempt from the (lyrical) imperfections that arise when human hands build them following the artist’s specifications.

A dialogue between Pompiers Courant à un Incendie (Firemen running to a blaze), by Gustave Courbet, 1851, from the Petit Palais permanent collection, and one of Othoniel’s pieces, 2021. Installation view, Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

Beauty has been a central subject throughout Othoniel’s career: either denying it at first, by means of gloomy sulphur (in French, “soufre” can mean both sulphur and suffer) sculptures, such as the ones seen at Kassel Documenta in 1992, or, as now, looking for what he calls a re-enchantment.

By his mid-career retrospective My Way, at Centre Pompidou, in 2011, Othoniel had already transitioned into the light, fragile, sensual and flexible domain of the glass. That is when the “enchantment” entered his Paris atelier, meaningfully called La Solfatara (after the Latin name for sulfur) and located at Rue de la Perle (Pearl Street). Legendary fashion trademarks such as Cartier and Louis Vuitton have since commissioned or sponsored his work and a perfume by Diptyque paid homage to his work at the Louvre. Likewise, the Dior Foundation is sponsoring the exhibition at Petit Palais.

Although he has experimented with different materials (wax, sulphur, metal, obsidian and gold leaf) and formats (drawing, painting and embroidery), he is best known for his sculptures composed of mirrored glass spheres in the form of necklaces that are eventually twisted into knots.

A visitor at Petit Palais observes one of Othoniel’s giant necklaces. Installation view, Jean-Michel Othoniel: The Narcissus Theorem, Petit Palais, Paris 2021. Photo: Ana Beatriz Duarte.

To explore the properties of the glass, he has partnered with, and learned traditional techniques from, artisans from Murano, near Venice, and small towns in Mexico, Japan and India. He had undertaken a similar quest for ancient forms of sulphur and obsidian, then recreated in the laboratories of the International Glass Centre in Marseille. Revisiting, honouring and recreating old traditions and folklore have long been part of Othoniel’s techniques.

Recently elected to the French Fine Arts Academy, Othoniel is today a French darling. But his work is also internationally known for the public art he has authored. Apart from the “double crown” entrance he created at one of Paris’s busiest metro stations, other permanent works can be seen in Doha, São Paulo, New Orleans, San Francisco, Amsterdam, Shanghai and various cities in Japan. Most of these works are created especially for their specific location, in a dialogue with its history, architecture and landscape. Many include water, another of his malleable materials of preference.

Jean-Michel Othoniel shows how his golden strings are born

Mathlapse - Recipe for a Wild Knot