Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, installation view, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 19 April – 13 August 2023. From left to right: Indian Madonna Enthroned, 1974; Ronan Robe #4, 1977. Photo: Ryan Lowry.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

19 April – 13 August 2023

by ELIZABETH BUHE

A seated woman greets us in Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She is Indian Madonna Enthroned (1974), and wears long braids, a thicket of beaded necklaces, a wool shawl and beaded moccasins. Her pheasant-wing hands hold a seminal text on Indigenous religions, God is Red (1973) by Vine Deloria Jr, which articulates a framework of relation governed by reciprocity. Across her chest, the Madonna’s beating heart of corn enacts this thematic connection between living things.

Smith is often recognised as a painter, and many of the 136 works here are paintings in oil, acrylic, or both. But Indian Madonna Enthroned introduces the multimedia strategy of bringing together materials in a non-hierarchical manner, even if their messages seem contradictory, a key lesson of collage that guides the show. This maternal artwork’s messages are multiple and profound: she critiques the patriarchal organisation of imported Christianity; and, with the United States flag as a lap blanket and a leather strap across her back marked “Property of BIA”, referencing the Bureau of Indian Affairs, she also critiques the genocidal US ideology of settler colonialism. The Madonna’s most striking aspect is her own face and that of the child carried on her back, each an ink and graphite drawing on paper, framed behind a gilded frame’s glass. Smith seems to say: we are not exhibits in a natural history museum. We are alive; we are here; we are creating things. It is a declaration of Native survivance.

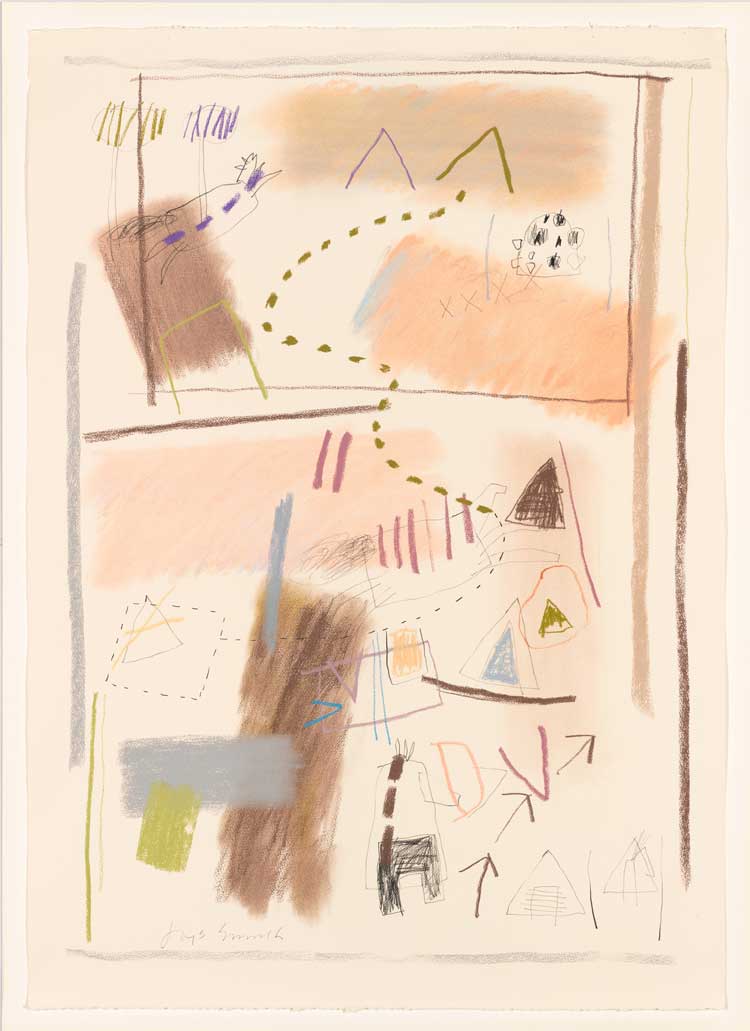

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Kalispell #3, 1979. Pastel and charcoal on paper, 41 3/4 × 30 5/8 in (106 × 77.8 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Altria Group, Inc. 2008.138. © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

Throughout the exhibition, Smith, who is a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai nation, succeeds in unsettling viewers’ naturalised frames of reference by offering history, geography and government policy through an Indigenous lens. She shows that treaties between colonisers and Indigenous people were flawed, histories were written inaccurately, and maps record arbitrary boundaries. In a gallery displaying her maps of the 50 states – perhaps her best-known body of work, begun in the 1990s – the overwhelming vertical runoff in blue, green, or orange paint of State Names Map I (2000) dissolves state borders, while only those state names that derive from Indigenous language are collaged to the canvas. This leaves some states, such as New York, unlabelled. Like the late 1970s pastel drawings such as Kalispell #3 (1979), of horses, tents and vegetation framed in loosely rendered grey or brown rectangles that trade the western convention of receding space for the flatbed space of the Plains people’s sled-like travois, these are maps of memory and experience rather than geopolitical boundaries.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Homeland, 2017. Oil and acrylic on canvas, 48 1/4 x 72 1/8 in (122.6 x 183.2 cm). Buffalo AKG Art Museum, New York; bequest of John Mortimer Schiff by exchange 2018:12. © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith. Photo: Tom Loonan and Brenda Bieger for Buffalo AKG Art Museum.

Here and elsewhere, Smith’s artistic strategy shows how strange and violent it is that non-Native people rarely question the appropriation of Native place names as a means of rationalising settler dominance. As the artist said in an interview recently: “I want everybody who walks in the gallery to say, ‘I don’t think I’ve ever seen a map shown that way.’” Her visual language is powerful and effective. Smith is explicit about where she stands and from where she speaks, and she is forthright about this standpoint in Homeland (2017), in which stunningly prismatic concentric circles and rays telescope to the location of the Flathead Reservation in Montana, where Smith grew up. Smith co-opts EuroAmerican cartography to prompt her viewers to see North America’s familiar outlines differently.

Installation view of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 2023. Photo: Matthew Carasella.

Smith returns to a set of icons in her work: horse, snowman, coyote, vest, trade canoe, US map, US flag. Of these, the latter two make the Whitney an especially apt location for the artist’s largest retrospective to date and the first retrospective of an Indigenous artist organised by this museum, given its institutional emphasis on the forward march of American modernism that captures quotidian life through figurative styles. In the 1950s, Jasper Johns used maps, targets and flags to show that artworks need not be mere images, but can function as the objects they represent. (Johns’ encaustic tiered Three Flags, 1958, is on view in a permanent collection show upstairs.) Smith masterfully pries icons from one context and places them in another so that their critiques signify differently. Since wall labels mention Johns sparingly and Robert Rauschenberg not at all, it seems the museum chose to avoid these overdetermined points of analysis so as not to reify them. A catalogue essay by Richard William Hill offers one interpretation by arguing that while Rauschenberg and Johns attempted to neutralise their content through collage, in Smith’s hands collage enacts a struggle for visibility. More specific than the work of exposing the constructed nature of our national history, then, Smith’s art realigns art history, an intervention that is especially significant because it is staged within the Whitney’s halls.

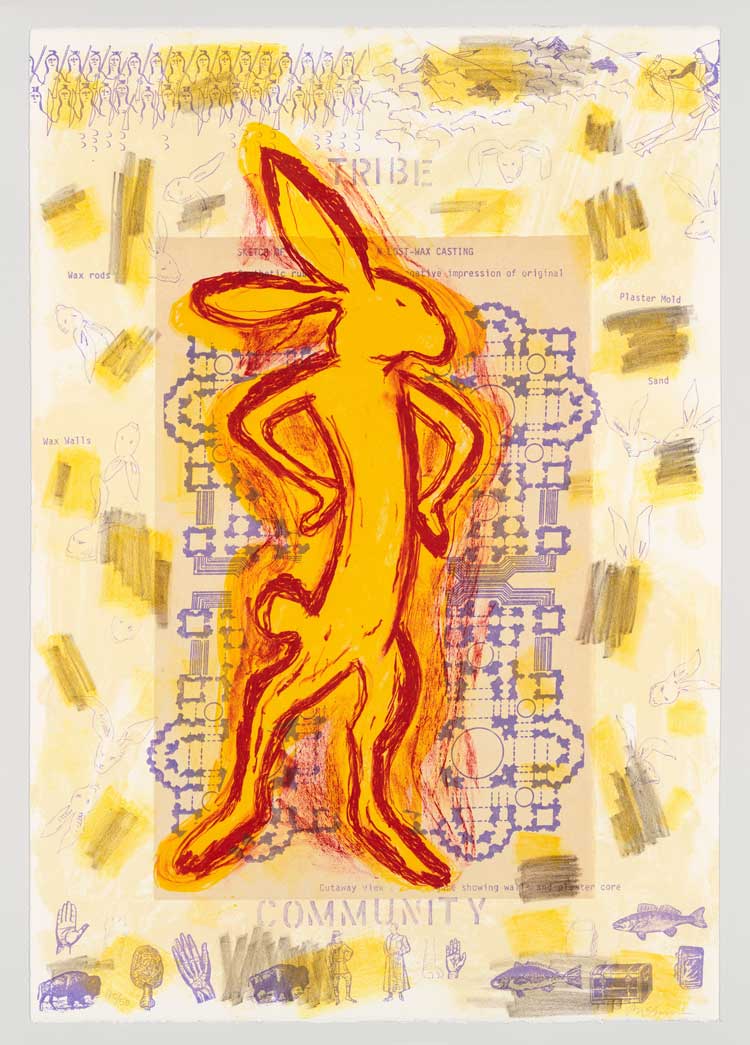

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Survival Suite: Wisdom / Knowledge, 1996. Lithograph with chine collé, 36 1/16 × 24 7/8 in (91.6 × 63.2 cm). Printed by Lawrence Lithography Workshop; published by Zanatta Editions. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Joe and Barb Zanatta Family in honor of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith 2003.28.1. © Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

The exhibition’s primarily thematic rather than chronological organisation owes to the strong internal coherence of Smith’s work, which consistently engages survivance, activism, kinship and critiques of imperialist and corporate chauvinism. Zigzag lines and pictographs populate the Petroglyph Park series of 1985-87, which mark Smith’s first artistic response to current events: a developer in Albuquerque, New Mexico, threatened to destroy a lava-rock cliff filled with ancient petroglyphs. In the early 90s, Smith’s visual language became more direct and her messages more biting. For instance, by repurposing the ubiquity of Barbie and paper dolls to her own ends, Paper Dolls for a Post-Columbian World with Ensembles Contributed by the US Government (1991) tells the story of settler colonialism. A pair of garments for parent and child speckled with pink and red dots is annotated “Matching Smallpox Suits for All Indian Families After US gov’t sent wagon loads of smallpox infected blankets to keep our families warm”, while a blue maid’s uniform prepares Barbie Plenty Horses to clean “houses of white people after good education at Jesuit school”.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights, 2015. Installation view, Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, 19 April – 13 August 2023. Photo: Matthew Carasella.

The following year, 1992, Smith made her first trade canoe painting, Trade (Gifts for Trading Land with White People), as an anti-celebration for the quincentenary of Christopher Columbus’s invasion. With the painting, Smith imagines loading up a canoe with mass-produced detritus and the ideologies attending this stuff to send it all back. From a chain above the canvas hang offensive children’s toys or sports memorabilia emblazoned with mascots. After being told that women could not be artists, Smith earned a degree in art education rather than studio art, and Trade and Paper Dolls show an incisive eye turned towards racist trinkets’ insidious pedagogical effects. Like the acid rain evoked by the silver spoons adhered to Rain (CS 1854), 1990, this, too, is a form of pollution.

Walking through the galleries, I paused at a modestly sized painting located near the show’s heart. Called Woman in Landscape (2021), this nude upright woman appeared like a messenger for the many truths Smith’s works speak. She interrupts a field of grey pictographs, palms held open and a large copper butterfly for a head. Printouts of the words “she”, “her” and “hers” float across the composition, merging contemporary conversations about pronoun usage with ancient matrilineal tradition and the sanctity of Mother Earth. What, I wondered, is the sound of a butterfly’s voice? We are listening for it.