Installation view with Battle of the Invalids, 2017. Photo: Peter Jacobs © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

by NATASHA KURCHANOVA

Irina Nakhova (b1955, Moscow) is, perhaps, one of the best-known contemporary artists from Russia: she has exhibited internationally for more than 30 years and represented her home country, the first female to do so, at the 2015 Venice Biennale. Despite her international renown and her long-time residence in the state of New Jersey, Museum on the Edge, now at the Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, is Nakhova’s first museum exhibition and her first retrospective in the US. It comprises nearly 40 works that embrace all periods of her career, from the 1980s to the present day. Nakhova’s talent was first noticed at the start of the 80s, when she initiated a series of installations that she called Rooms, in which she converted her own apartment into a living painting, a space in which she could escape from the mind-numbing boredom of Soviet everyday reality. These projects were influential for a generation of Moscow conceptualists, including Ilya Kabakov (b1933), whose famous installation The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment (1988) would have been impossible without Nakhova’s Rooms. Her project for the Russian Pavilion at the 2015 Venice Biennale also involved work with the site-specific nature of the space – she painted an entire floor of the pavilion with a red-and-green camouflage pattern, brilliantly referencing Russia’s siege mentality and nationalist leanings, as well as her own installation history.

For her retrospective exhibition at Zimmerli, Nakhova has also worked with space, breaking up the traditional layout of the rooms and opening it up to accommodate her installations. As a result of her intervention, the ground floor of the museum looks completely transformed, reflecting the artist’s longing to get out of the confines of traditions and embrace experimentation. Studio International spoke to Nakhova shortly after the exhibition’s opening.

Natasha Kurchanova: You are a well-known artist with many important exhibitions under your belt, including solo shows at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts and the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. You also represented Russia at the 2015 Venice Biennale. How is the exhibition at Zimmerli Art Museum special for you?

Irina Nakhova: This exhibition is important because it is my first personal museum exhibition in the US.

NK: How did it come about?

IN: I worked on this exhibition for about a year. Jane Sharp and Julia Tulovsky, curators at Zimmerli, proposed this show to me. It was put together from works available in this country. In fact, I brought only one work with me from Moscow – Battle of the Invalids (2017). The rest of the works are from the Norton Dodge Collection at Zimmerli, or from my personal collection.

Installation view with Battle of the Invalids, 2017. Photo: John Tormey © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

NK: This retrospective makes it obvious that many of your works are related to museums.

IN: That’s how it turned out. I looked at the exhibition space and thought about how I could destroy it first and then remake it. I wanted the space to come alive in such a way that it would bring a new kind of experience to museum visitors here. Zimmerli is a good museum, but it has a specific function: as a university museum, it mostly serves a student population. I wanted to transform it into a museum of the 21st century by literally breaking its walls. Jane Sharp and Julia Tulovsky, as well as the director of the museum, Thomas Sokolowski, also wanted the same thing, and so I was able to implement my vision. This transformation was made possible by a large donation given to the museum last year, which also enabled publication of the catalogue.

NK: I think you succeeded in enlivening the space of the museum, just as you set out to do. Yours is one of the most memorable exhibitions I have seen there. Did you come up with its title as well?

IN: Jane Sharp proposed the title.

NK: So, what you have done in this museum is a continuation of your work with space in general, beginning with a series of Rooms in 1983, when you remade your own apartment several times. What kind of meaning does work with space have for you?

IN: If I am offered an opportunity to work with a space, then I think about how I can do that. Spaces differ from one another. For example, there are spaces that cannot be altered radically. Only a few alterations can be introduced into them to revitalise them, but that’s all. Then there are spaces that are absolutely dead, and they should be approached differently. Ordinarily, people do not think much of the spaces they inhabit. After all, they are ordinary – the apartment, the kitchen, the street, the swimming pool … But, beginning with the Rooms, the space I found myself living or working in became a very personal issue. I had to master it in a certain way. Everything located there had significance, and there are many gradations of meaning created by the things within.

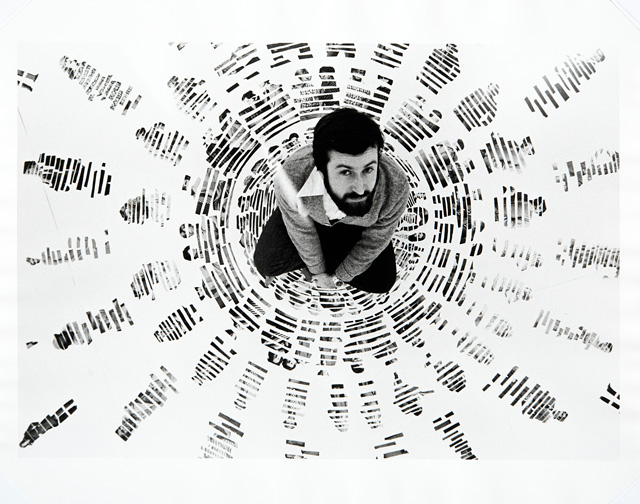

Irina Nakhova, Room No. 1, 1983. Gelatin silver print on paper. Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, Collection Zimmerli Art Museum. Photo: Peter Jacobs © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

Spaces are difficult to categorise because they can be spaces of remembrance, spaces of the past and spaces of the future. Each space reveals its possibilities to me. I know what may activate it. When a person is not familiar with an environment, then she finds herself in a challenging situation because she needs to adjust to this space, otherwise she does not know how to behave. If it is a challenge for the viewer, it is a challenge for me as well. So, I work with space in such a way that it becomes interesting for me. It is important for me at every turn that I feel compelled to relate to it, to work there, to feel comfortable in it. With my installation works, I want to convey that it is possible to be somewhere and feel differently because of that. I try to open up the appeal of the indefinite nature of space to the viewer. To do that, you have to activate all your senses – sight, hearing, touch, smell. This experience is not comparable to being in the Exploratorium [a museum in San Francisco that bills itself as “an ongoing exploration of science, art and human perception – a vast collection of online experiences that feed your curiosity”] because such things are for the kids. For adults, we are talking about their lives, not their fantasies. Their lives are an Exploratorium. It is interesting to have to explore things around you, both old and new, and question everything you see. When you find yourself in a space that is new and unexpected, you begin to think about it. It stimulates your brain, your sight: your entire body engages with this space.

Installation view with Skins, 2010, Queen, 1996, and Battle of the Invalids, 2017. Photo: John Tormey © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

NK: When I looked at this exhibition, I noticed that your works combine tactile and optical sensations. Sometimes, the works impel the viewer to touch them – as in Skins (2010). Sometimes, this opportunity is completely excluded – as in Gaze (2016-19). In Camping (1990), you painted ancient statues on army cots, optical sensations are superimposed on tactile ones doubly, in a sense – by transforming sculpture into a painting and by superimposing it on an object. Visual art has to do with vision, so your interest in optical sensations is well understood, but could you explain your persistent interest in tactility?

IN: I began my career as a painter. So, in the beginning, I was interested in illusion. Then, in Rooms, this illusion was applied to my works in three dimensions, which later came to be called installations. Visuality is more than the eye; it includes tactility, which is a primary sense. The world is very diverse; it does not include only visual sensations. This is why I diversify my work to the utmost possible degree, including audio pieces and sculpture apart from paintings and videos. My mode of expression depends on the nature of the project. It depends on the most effective way I can express my thought. I always incorporate new sensations into my work.

-edit.jpg)

Installation view with Camping (1990) and Seven Masterpieces, 2013. Photo: Peter Jacobs © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

NK: In this exhibition, dedicated to the museum as an institution, you have several works related to museums. For example, in Seven Masterpieces (2013), you came up with hilarious “museum guides”, which mix fact and fiction in providing explanations of non-existent works of art.

IN: Have you listened to them? They are very funny. They pertain to non-existent paintings that are supposed to be there. They are made-up funny stories. I like writing these fake stories that have some facts in it. It is fun. In their humour, the stories are similar to the ones in Skins. Like Skins, Seven Masterpieces references absurdities we encounter in our everyday life. I started doing them a long time ago, to highlight the importance of imagination in our psychological makeup. Some people ask me: “Are these real stories? Are these real skins?” I am open to any kind of interpretation with these works.

Installation view with Queen, 1996. Photo: John Tormey © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

NK: One of my favourite works in this exhibition is Queen (1996). Could you say a few words about it?

IN: This work was partly made in Detroit, where I lived at the time, and partly made in Sweden, for an exhibition celebrating the 600th anniversary of the Kalmar Union, which made Queen Margaret I the ruler of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. The union lasted more than 100 years and she is historically recognised as a great, strong leader. My idea was that we can understand certain things and historical phenomena only by looking at them from a distance. The Queen is almost a literal illustration of this phenomenon: you see her from a distance as a queen, but as you approach her to look closer, she turns into a giant phallus.

NK: Is the video next to it part of the work?

IN: It’s a short video, showing my hands at work on everyday tasks – cooking, cleaning, taking care of things – with very short visual inserts of a man running and sticking a pitchfork into a sack of hay with all his might. This video was made for the same exhibition, and it can be shown either together with Queen, as a commentary, or independently.

Irina Nakhova, video still from a work in Gaze project (2016-2019). Collection of the artist. © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

NK: The latest work in which you use video exclusively is Gaze (2016-19).

IN: I was invited to make an intervention at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow. And I came up with an idea that I thought was the most appropriate for a museum: how do I and other people look at a work of art, painting in particular. In creating these videos, I was trying to show how people concentrate their attention on various parts of a painting by making a part of the painting sharp and then moving the focus elsewhere on the canvas. I did not use any device that measured exactly how people view art: it is not a science project. I used my imagination instead. People are different and they see different things in the same object.

I like going to museums and finding life in dead objects. I would like viewers to experience the same excitement. I want my works to provoke personal findings and curiosity that engage them to experience the world in a new way. For me, the museum in general, and this museum in particular, is a lively space. It’s a space where I can think and put things together. I want to make it relevant to the present time.

NK: Could you comment on your work Battle of the Invalids? It is the centrepiece, of sorts, of the exhibition.

IN: I made this piece two years ago for the Pop/Off/Art gallery in Moscow. In that gallery, the installation could be viewed from above. These Invalids were battling with each other under the control and direction of the visitors who stood on a balcony above. There is no such balcony in this museum, so the visitors stand on the floor next to the work to control the moving figures. The work is a commentary on the absurdity and senselessness of our everyday life, which is the focus of my work. If you are living in this world, you cannot avoid its violence. In Battle of the Invalids, the invalids are on “wheelchairs”– platforms, operated by the viewers using joysticks. One of the triggers for the Invalids was my observation of Russian war veterans begging for money in Moscow subways. A mafia guy, who exploited them by taking the money they made, managed these disabled veterans. It was horrible to see.

On the other hand, an encounter with ancient sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art also evokes very strong sensations – they are also literally crippled by time and war. When I go to the Met and see many sculptures of different cultures and time periods, it is not always clear whether the objects are simple artefacts or high art. Sometimes, they are both, and this is how I see the Invalids.

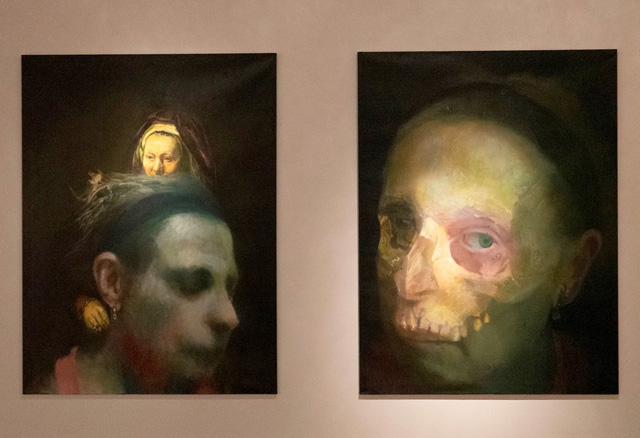

Installation view with Vanitas I and II, 2017. Photo: John Tormey © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

NK: What about your paintings?

IN: Some of them are my latest work, and you can see them in the room where Battle of the Invalids is installed. Like the previously mentioned videos, they relate to the subject of the gaze, especially Vanitas I and II (2017). My painting Kiss (2017) was inspired by François Boucher’s Hercules and Omphale (1730-1739). In all of these works, I wanted to address the subject of vanitas, the flow of time and the frailty of life, of our existence.

Irina Nakhova, Kiss, 2017. Diptych. Oil on canvas. Collection of the artist. Photo: Natasha Kurchanova © 2019 Irina Nakhova.

In Kiss, you see that certain details are emphasised, such as the nose, the ear and the lips. The eyes are closed. So, what we are looking at is directing us towards other senses, not vision. We have to think about the metaphoric meaning of this work and apply it to us as well: are our eyes closed as well, just as they are in the depicted figures? There are many correspondences of these paintings with the videos from Gaze.

These paintings are connected with each other. My big self-portrait as the skull – Vanitas 2 (2017) – is also one of the gazes. It was shown in the Pushkin Museum, but not here. It’s a commentary on time or eternity, rather.

NK: Also, at this exhibition, I was interested in seeing the works that were included in your first large one-person exhibition in the US, which took place in 1992 in the Phyllis Kind Gallery.

IN: I chose only a few works from the Phyllis Kind show, which contained a lot more reliefs, which you see here, and other works. For that show, I invented a fictional story as a narrative. It was a story from the future. It went as follows: a catastrophe descended on the gallery, and all the paintings and works contained therein turned into ruins. It was like a modern-day Pompei. So, I had pieces of paintings embedded in reliefs. The story was that archaeologists from the future discovered this part of the show. That exhibition also contained video works, which have since vanished. The video works imitated observational cameras, which supposedly captured a series of events that preceded the catastrophe. That exhibition was also dedicated to museums, I guess. It could be called Pompei of the Future.

NK: It seems that for you, this exhibition is a look at your work “in perspective” so to speak, considering its role in the context of a museum, as a museum object.

IN: I never think of my work as career-oriented or of myself as making a “career”, whether artistic or museum-based. Rather than a “career”, I call what happened to me a more or less lucky concatenation of circumstances. I do not get paid for what I do, so it’s not a career for me. Art is not a profession for me, but rather my way of being.

• Irina Nakhova: Museum on the Edge is at the Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers University, New Jersey, until 13 October 2019.