Albrecht Dürer. Christ among the Doctors, 1506 (detail). Oil on panel, 64.3 x 80.3 cm. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid (1934.38). © Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid.

The National Gallery, London

20 November 2021 – 27 February 2022

by BETH WILLIAMSON

It has been nearly 20 years since any significant UK exhibition of the work of Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528). Born in Nuremberg, Germany, he remains one of the most prominent artists of the European Renaissance. This exhibition at the National Gallery uses Dürer’s travels to take visitors on a journey through a phenomenal range of works, most of which have not been displayed in Britain before. More than 100 paintings, drawings, prints and documents together tell the story of the artist’s travels: to the Alps and Italy in the mid-1490s, to Venice 1505-07; and to the Low Countries 1520-01. These three significant journeys brought him into contact with other artists, people and places that seem to have fired his intellectual curiosity and artistic imagination.

After Albrecht Dürer. The Painter’s Father, 1497. Oil on lime, 51 x 40.3 cm. © The National Gallery, London.

Dürer’s early travels were like those of many young artists. He trained first with his father, before being apprenticed to Michael Wolgemut, a painter and woodcut designer. Dürer’s The Painter’s Father (1497) is shown in the form a 16th-century copy but still conveys a strong sense of the dignity of the Hungarian goldsmith who settled in Nuremberg in 1455. Following his initial training, Dürer first travelled along the path of the Rhine, visiting towns along the way. On his return to Nuremberg, he set out again, this time over the Alps. By 1500, he was well-established and respected as an innovative printmaker. His woodcut from the Apocalypse of 1511 (originally published in 1498) is quite simply astounding.

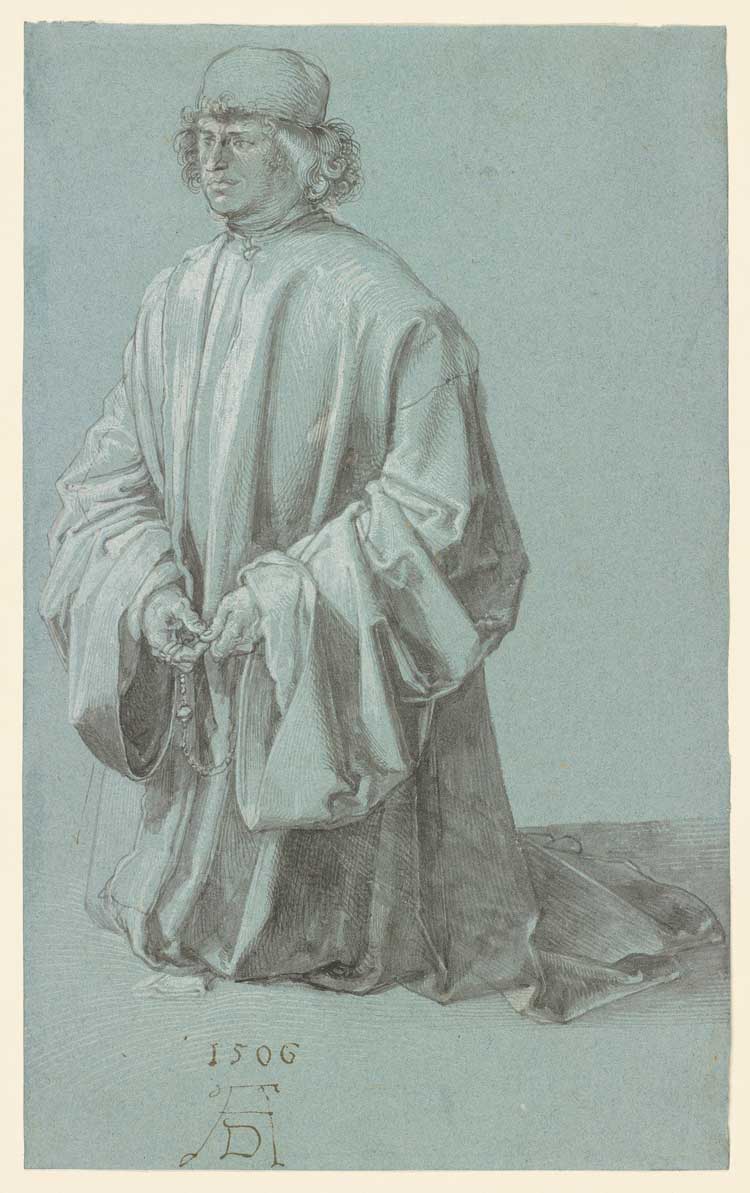

Dürer’s travels to Venice in 1505-07 are recorded in his epistolary exchange with his close friend and leading humanist in Nuremberg, Willibald Pirckheimer. He also recorded his friendship in Venice with Giovanni Bellini, noting: “[He] is very old and yet he is the best painter of all.” While Dürer’s reputation for printmaking was secure, some Venetian painters were critical of his ability to handle colour. His altarpiece the Feast of the Rose Garlands was his riposte to them. Christ Among the Doctors (1506) was painted at this time, too, and is shown in this exhibition along with one of Dürer’s studies for the painting. Hand with Book (Study for Christ among the Doctors), from c1506, was created on paper made from blue rags. Dürer made other drawings on this light-blue paper while in Venice, including the beautiful study Kneeling Donor (1506), also on show. You begin to get a sense of his connections in Venice and how that influenced his painting and related works.

Albrecht Dürer. Kneeling Donor, 1506. Brush and black ink and wash, with white opaque watercolour, with pen and dark ink, on blue paper, 32.4 x 19.8 cm. The Morgan Library & Museum, New York. Purchased by Pierpont Morgan (1837–1913) in 1909. © The Morgan Library & Museum, New York.

Dürer’s interest in painting waned and when he returned home from Venice, he was employed by Emperor Maximilian I, making large woodcuts for him, as well as portraits. Following Maximillian’s death in 1519, Durer travelled north to Aachen and to the Low Countries. It was at this time, too, that he became interested in the beliefs of Martin Luther, who had challenged the authority of the Roman Catholic church. Dürer was welcomed at his different destinations: “In Brussels, I ate, lodged and drank with my Lords of Nuremberg, and they would take nothing from me for it. Likewise in Aachen, I ate with them for three weeks, and they took me to Cologne and here, too, would accept no payment.” With this level of support, he was free to focus on developing his printmaking.

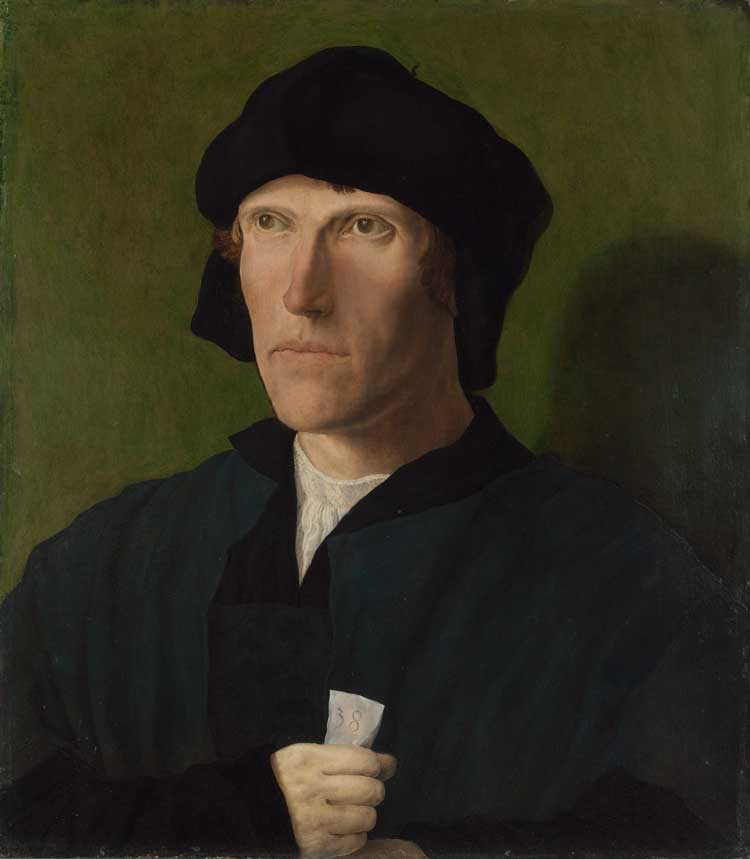

Lucas van Leyden. A Man aged 38, about 1521. Oil on oak, 46.7 × 40.8 cm. Presented by the children of Lewis Fry in his memory, through the Art Fund, 1921. © The National Gallery, London.

Dürer visited the artist Quinten Massys while in Antwerp and Massys’ Portrait of Aegidius (Pieter Gillis) (1517) is on display here alongside Dürer’s work of the period. Also, on display is A Man aged 38 (c1521) by Lucas van Leyden, a printmaker known to Dürer. Works such as Jan Gossaert’s Elderly Couple (c1520) and Massys’s Desiderius Erasmus (1517) help to represent the artists and people he encountered at this time. It was not just the people, but the material fragments of the place itself that was important to Dürer, as can be seen in his Portrait of a Young Man with a Hat (probably 1518). The drawing is made on Venetian paper retained from his earlier travels. While the hat is typical of Augsburg in Germany, visited by Dürer in 1518, it is known that he also met people from Augsburg in the Low Countries. This portrait, then, is a good example of where different journeys and influences come together in a single work.

Quinten Massys. Desiderius Erasmus, 1517. Oil on oak panel, 50.5 x 45.2 cm. Lent by Her Majesty The Queen. Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020.

Albrecht Dürer. Lady from Brussels, 1520. Pen and brown ink, 16 x 10.5 cm. The Albertina Museum, Vienna (3161). © Albertina, Vienna.

In Antwerp, a centre for international trade, Dürer met people from all over the world. He observed and recorded his impressions of people, animals and townscapes. His sketches in pen and iron gall ink, and in silverpoint, often did not survive. In this exhibition. a selection of those sketches shows the range of subjects he encountered from Lady from Brussels (1520) to Two Livonian Women (1521), from Sketches of Animals and Landscapes (1521) to Bust of an Old Man (1520-1). Here we get a sense of a lively environment with an ever-shifting international community, and a cosmopolitan city that Dürer found stimulating and was receptive to.

Albrecht Dürer. Two Livonian Women, 1521. Pen and brown ink, watercolour, 18.4 × 19.5 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris (20DR). © RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / Thierry Le Mage.

It is inevitable that some of Dürer’s artistic exchanges were more important to him than others. Joachim Patinir and Gerard David were two of those artists whose work interested him. Patinir was a skilled landscaped painter as his River Landscape with Saint Christopher (date unknown) shows. David’s The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donor (probably 1510), on display in this exhibition, may have been a source of influence for Dürer’s own painting of the Virgin and saints at this time.

Gerard David. The Virgin and Child with Saints and Donor, probably 1510. Oil on oak, 105.8 x 144.4 cm. Bequeathed by Mrs Lyne Stephens, 1895. © The National Gallery, London.

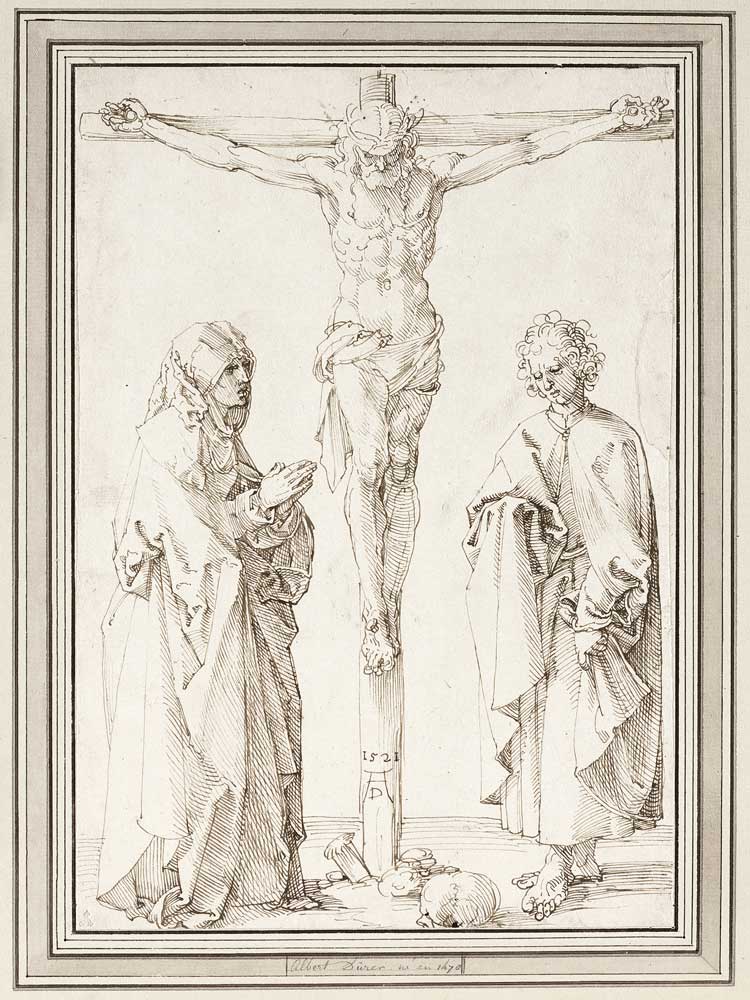

While he was in the Low Countries, Dürer began to experiment with new ways of conveying the crucifixion story, an experiment that continued on his return home. At this time, he was acutely interested in the ideas of Luther. In 1517, Luther published his 95 Theses, and the adoption of his views had a significant impact on the production of religious imagery. Dürer’s The Crucifixion (1521), for instance, is pared-back with a focus on Christ on the cross.

Albrecht Dürer. The Crucifixion, 1521. Pen with brown ink, 32.3 x 22.2 cm. The Albertina Museum, Vienna (3169). © Albertina, Vienna.

This is a fascinating exhibition that demonstrates the importance of encounters with people, places and ideas for Dürer’s paintings, drawings and printmaking. I really appreciated how his diverse encounters were brought together, showing points of reference, sources and influences afresh through his work and the work of other artists. Ultimately, it is about the importance of travelling elsewhere with open eyes and minds, and using those experiences to record observations, both on journeys and at home, in innovative ways.