by JANET McKENZIE

Craig Gough (b1938) grew up in Perth, Western Australia, where he attended art school and teacher training college (1958-65). He had achieved much success with exhibitions, teaching and art criticism before moving to Melbourne in 1974, to take up a lectureship in painting at Caulfield Institute of Technology (now Monash University). In Melbourne, his work caught the attention of Patrick McCaughey, then director of the National Gallery of Victoria, who included Gough’s work in numerous key exhibitions, and the British abstract artist John Walker (b1939), who was dean at the Victorian College of the Arts (1982-86). Their opinions played an important role in his career. In 1994, after 20 years in Melbourne art schools, Gough retired early to paint full time. Since then, he has lived between the towns of Castlemaine and Maldon in central Victoria, with his partner and fellow artist, Wendy Stavrianos.

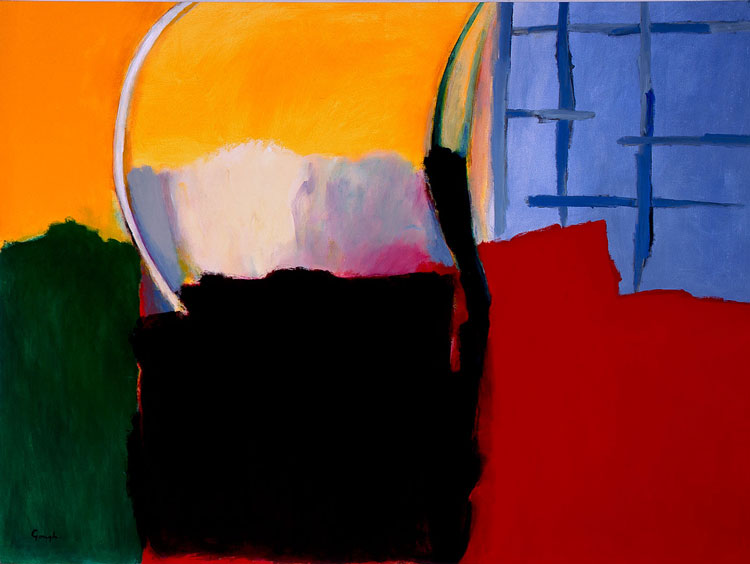

Craig Gough. Blue Space 3, 2007. Acrylic on canvas, 183 x 274 cm. © the artist.

His powerful abstract work has received many awards and art prizes. In 1988, he was awarded the residency at Arthur Boyd’s studio in Italy, where many Australian artists, through Boyd’s generosity, were able to work for three months in the heart of Tuscany, close to Florence, Pisa, Lucca and San Gimignano. Gough and Stavrianos have travelled extensively through much of Europe and the US – particularly New York – enabling concentrated study in museums. More recently, Gough has travelled to China and Japan. His works are held in major public galleries, corporate, institutional and private collections in Australia and overseas.

Janet McKenzie: Looking at your powerful drawings from the 1970s, when you first moved to Melbourne from Western Australia, I thought they shared the energy of subject matter and method with Jan Senbergs (b1939, Latvia; arrived in Australia in 1950) and Peter Booth (b1940, England; arrived in Australia in 1958). They were both important artists to migrate to Australia. Were you conscious of their work?

Craig Gough: When I first arrived in Melbourne from Perth, I became aware of the Melbourne artists who were working in the other art schools there. There were a number of artists who lived near me in Sandringham: Roger Kemp, Fred Cress, Alun Leach-Jones, Sandra Leveson, Clive Murray-White, John Davis, David Wilson and Steve Spurrier. I found out later, that we were referred to as the “Hampton mafia” (Hampton being the adjoining suburb). We saw each other from time to time. I didn’t meet Senbergs, or see his work, until much later.

Craig Gough. Sandringham 111, 1982. Acrylic on paper on canvas, 152 x 358 cm. National Gallery of Victoria collection. © the artist.

Through the 70s, I was working in an abstract manner of colour field or lyrical abstraction begun in Perth. By the late 70s, I started working more figuratively and tonally and I feel that my darker palette was a reflection of living in Melbourne with a very different climate from that in Perth. I lived close to the water, on Port Phillip Bay, and returning home from work and looking down to the water and the palm trees silhouetted against the setting sun became my subject. I was given a large roll of paper, the industrial waste material from a plastics factory. It was 152cm wide and plasticised on one side only, so was ideal for working in acrylics, once I had cut a length (around four metres) and stapled it to the wall.

Craig Gough. Walmer 2, 2006. Acrylic on canvas, 183 x 284 cm. © the artist.

I chose the large horizontal format as I felt that it suited my subject. I was able to begin work straight away and changing media from oil to acrylic was really liberating. I made a decision to do each work in one sitting without reviewing it the next day. I wanted to avoid being fussy, so I just stapled another sheet on top and started another work. The change in media and the speed of execution, plus a combination of a lot of acrylic line drawing into the paint surface and constant overlays might explain the energetic aspect of these works and the accompanying drawings in charcoal that you are referring to. All these works were done from memory of what I had experienced looking down the street and living in the area.

Craig Gough. Sandringham, 1982. Acrylic on paper on canvas, 152 x 358 cm. Curtin University, Perth WA collection. © the artist.

Thinking back now, it was a passionate response to what I had seen, and a bit crazy. I wasn’t thinking commercially. Having been given the paper meant there was no expense incurred, so I was not concerned with anything other than making the images (around 20 of them). It was what I needed then. I continued working on this paper with subsequent other ideas, because I liked the process and what the finished works looked like. Later, I found a way to adhere the finished paintings to canvases.

The Sandringham works were each completed in four or five hours, and I usually started at about 8pm or later, as I had family duties, such as reading stories to the children. The nights were my studio time, and once or twice I worked all through the night and went to work the next day. I don’t know how I managed that then, but I guess I was driven by an inner compulsion. Many other artists I knew who worked in art schools were also night workers.

JMcK: John Walker was an important figure in your career around this time?

CG: John Walker and I both showed at the Christine Abrahams Gallery in Melbourne in the 80s. When I exhibited my Sandringham works (1983), John said he would like to swap a work with me, though, sadly, he returned to America before that happened. His own exhibition there, later that year, was of his Alba paintings, with his wonderful juicy paint. It had a big impact. Like many artists in Australia, my partner, Wendy Stavrianos, travelled from interstate to see the show and she and I still talk about his work and what a brilliant and inspiring artist he is and a very generous man. At the Knoedler Gallery in New York, in 1988, we were lucky to see his exhibition A Theater of Recollection: Paintings and Prints, which had travelled from the Boston University Art Gallery.

Craig Gough. Sandringham No 23, 1983-4. Acrylic on paper on canvas, 152 x 305 cm. Private collection. © the artist.

I usually saw John only at exhibition openings and he invited me to talk to his students at the Victorian College of the Arts , but his example via his work was extremely important to me and the brief conversations I had with him kept me on track. I have only come into contact with a small number of people who have demonstrated to me the idea that painting is a very serious pursuit. John’s dogged persistence model has kept me focused.

Craig Gough. Spatial Red, 2013. Acrylic on canvas, 137 x 198 cm. © the artist.

JMcK: The large scale of many of your abstract paintings plays an important role in how the viewer shares your creative processes. How did your immersive canvases evolve?

CG: The desire to work large was conditioned by my own experience initially. While I’m painting, I feel that I’m in the work, inside it! It’s a full-body thing that is obviously not the same as working small, which I also do. The larger work allows for big gestures, which I am a part of – whereas the small hand gesture produces an object that needs to be looked at more closely. I suppose you could say if the work is about colour, you need to express this with big expanses of it. I want to be overpowered by the work. When I did the large works on paper, it was also about letting go and immersing myself in them.

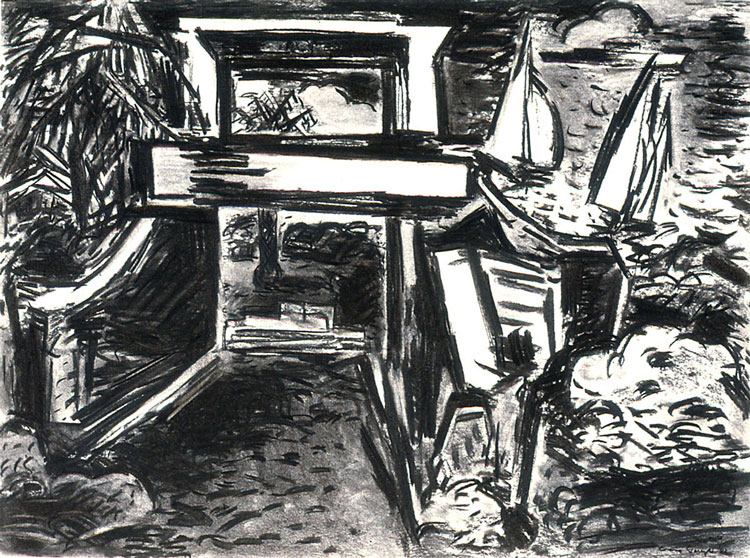

Craig Gough. Rotunda, 1982. Charcoal on paper, 56 x 76 cm. Private collection. © the artist.

For a viewer, it’s a different experience. I feel that when a viewer comes in contact with my large paintings, they will feel confronted by them and will feel something different from looking at a small work, which is more like looking at an object. I guess I want the viewer to feel that they are looking at a painting rather than a decorated object or an embellished form. I don’t want to corrupt the motif by using some kind of special effects to demonstrate cleverness. Each work begins as an exploratory process that aims to discover something else about the subject, as it moves toward being a painting.

JMcK: Your work shares the immediacy of the drawn mark and the metaphysical abstract language that alludes to music and poetry. Can you explain how you have felt apparently at ease in both forms of visualisation?

CG: In my early 20s, I played the saxophone semi-professionally in jazz groups. Now, I listen a lot to jazz while I am painting. For me, improvisation in painting is a lot like jazz. You have a group of chords that have a particular sequence and there are special rhythms and you need to improvise, to come up with a coherence of the idea that produces a special unity, even though you take a lot of liberties. Although my paintings are not sounds, I would hope that the works have a special identity as a picture – a painting – and not just an object. Not very many people can fully understand jazz. It’s not just bouncy toe-tapping rhythm or something played on unusual instruments or whatever. It is much deeper than that. It can take something prosaic and make it into something that is really extraordinary. You have to really listen to it. Abstract paintings expect the viewer to really look as well. In my case, I would hope that the viewer is really looking and becoming absorbed in the work, not trying to find the figurative form hiding in there somewhere.

Craig Gough. Primary Garden, 2006. Arylic on canvas, 183 x 244 cm. © the artist.

In 1977, I had an exhibition of lyrical abstract paintings in a Melbourne gallery. I had a jazz group at the opening and I “sat in” for a small part playing my saxophone. I gave the paintings titles alluding to jazz, such as: Be Bop, Riff, Jam Session, Downbeat. So if you were looking for the figurative form, the title wasn’t going to help you. I would like to think that I am bringing to my paintings the same form of emotion and improvisation that jazz offers.

JMcK: You have not scaled down your vast paintings in your 80s? Can you describe why you continue to work on such large canvases?

CG: Madness! I can’t stop from continuing to seek out the resolution in the next work. I am fortunate that I am able to function (in my head), as though I was still in my 30s or 40s although perhaps not as agile? It’s what I do! I couldn’t imagine what my life would be like if I wasn’t painting and drawing. That means taking a subject and doing something to it, then something else, and something else. Of course, many artists have done this over centuries. I am thinking of Paul Cézanne’s variations of Mont Sainte-Victoire or Henri Matisse’s dancers.

Craig Gough. Arrangement in Blue, 2004. Acrylic on linen, 152 x 198 cm. Private collection New York. © the artist.

JMcK: Arrangement in Blue (2004) would appear to refer to Wassily Kandinsky’s musical notations and to the history of abstraction in the early 20th century; Structured Field (2004) to aspects of an internal life, to architectural space, to a particular place or moment. Is it possible to explain your preoccupations then and now?

CG: Both of these works derive from the same subject matter. Then, as now, in current works, they began as inspiration from my garden. Those paintings came from looking at a veranda pole that had a wisteria vine going up and around it. Other elements are like the triangular roof of a garden shed, a low wall and garden steps. I’m quite happy with your interpretation, because you have seen these works as paintings and not illustrations of the garden. The garden offers an endless number of forms to start me off on a quest, making a large number of works. I guess my choices have brought me to where I am. I continue to find the garden a place where I can explore painting. Fortunately, the subject is close at hand.

Craig Gough. Structured Field, 2004. Acrylic on linen, 183 x 198 cm. © the artist.

I’m unlike some people, who feel they need to travel vast distances to discover subjects that they wish to paint. An important element in my thoughts is my own naivety. You might refer to this as “handwriting”. It is unique to every one of us. We were all taught to write, but our own naivety comes to the fore and is immediately recognisable. It’s the most precious element an artist has. It’s a unique look unlike anyone else. I’m not sure that this is an issue for those artists who work as photo-realists. Handwriting is like personal fingerprints or DNA.

Craig Gough. Dialogue, 2014. Acrylic on linen, 91 x 107 cm. © the artist.

JMcK: Two paintings: Dialogue (2014) and Garden Colour Construct (2019) allude to art as being an essential form of communication and to the manner in which artists work with a set of formal components – colour, shape, composition, line. Can you describe these two works?

CG: Both of these are relatively recent works and began from looking at the garden. Yes, they do have those formal qualities. Colour, shape composition and line are my current preoccupations and, although they were done a few years apart, they share the same attitude. A musician friend once described jazz improvisation as “the same chords with different fingering”. I seem to have been painting the same picture over and over again, trying to find something else to say about it. I’m still excited by what I am doing.

Craig Gough. Garden Colour Construct, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 152 x 167 cm. © the artist.

JMcK: How has the pandemic affected the way you are working?

CG: Luckily, the pandemic has hardly affected me in my work in the studio. But going to galleries and exhibitions has had to be curtailed during the long period of the shutdown. Social distancing is my default position anyway.