.-You-Mountain,-You-River,-You-Tree,-2022-1000.jpg)

Barbara Gamper, Somatic encounters - earthly matter(s). You Mountain, You River, You Tree, 2022. Performance at Vallunga, Selva Gardena. Commissioned by Biennale Gherdëina 8. Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo.

Ortisei and assorted locations around Val Gardena, Italy

20 May – 25 September 2022

by VERONICA SIMPSON

The alpine region in early summer is a true delight, especially the extraordinary landscape of the Dolomites in north-eastern Italy. As the green, pine-clad peaks of the South Tyrol give way to this Unesco World Heritage-protected mountain range, with its distinctive, grey, rocky protuberances thrusting upwards into the clouds like fat, gnarly fingers, its dominance in your field of vision is mildly terrifying but utterly exhilarating. It is an excellent location for an art festival that asks us to think about how we care for our fellow planetary “beings” (or “more than human beings” as the new eco-activism terms them), such as mountains, animals, plants and rivers. This notion draws on the legal designation of “personhood”, which has become increasingly important for environmental activists around the world, in their battle to protect the wonders of nature from human excavation, extraction and exploitation.

The Biennale Gherdëina has been celebrating culture and nature in this location since 2008 – though, to be clear, its main base of Ortisei is a few kilometres from the Unesco-protected site in the Vallunga nature park. The biennale started as a collateral event for 2008’s Manifesta 7, with just five artists, but it has grown incrementally since, in artist contributions and profile. This year, the programme is stepping up another gear, in its expansion beyond Ortisei into the neighbouring valleys, and in the escalation of curatorial star-power.

Biennale Gherdëina 8. Martina Kyriaki Goni and Giles Round, exhibition view at Sala Trenker, Ortisei, 2022. Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo.

This year we see a pairing of Lucia Pietroiusti, the Serpentine Gallery’s strategic consultant for ecology, and Filipa Ramos, who is a writer and curator and the director of the Contemporary Art Department in Porto. They have chosen carefully from a wonderfully eclectic artist portfolio of eco-activists and radical thinkers, some of whom are also artists from this region. With the theme Persones Persons, the idea is to elevate nature in all its forms to become much more of a participant in this year’s biennale - and in our thinking in general. As the curators say in the catalogue introduction: “Dialoguing with the alpine valleys, mountains and skies of Ladinia [the local name for the region] and celebrating the multitude of living forms – human, animal, vegetal, mineral, mycological persons – that populate them, the stories of Persones Persons are told … through exhibition, encounters, performances, songs, storytelling, hugs, books and other streams of exchange.”

The works selected, from about 24 artists or artist entities (some work as collectives or in couples), address one or both of the two main strands, to do with personhood (as outlined above), plus “transhumance” – the seasonal movement of people and animals across a territory, or, as Pietroiusti put it at the opening: “The way the relationship between animals and landscape shapes the landscape over time.”

Biennale Gherdëina 8, exhibition view at Sala Trenker, Ortisei, 2022. Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo.

This is not the kind of biennale where random international artists (or their works) are helicoptered in to adorn and embellish the local terrain. This team ensured that any participants who are not based in the region had time to spend in the mountains to evolve their response, becoming, says Pietroiusti: “Fine-tuned to the local differences … attuned to the weather, the shape of the clouds, to the way the trees change, how the animals move, how the water rises and falls.” Two local artists were also selected from a range of makers working in the region – one of whom, Bruno Walpoth, was also in the 2014 iteration - and all artists were taken on workshop visits and encouraged, where possible, to collaborate with the artists and artisans based there. The intention of the biennale’s founder and director, Doris Ghetta, was that the festival should enrich local artists’ practice through exchanges with international artists, as well as representing the region’s own home-grown assets and attributes.

Biennale Gherdëina 8. Exhibition view at Sala Trenker, Ortisei, 2022. Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo.

And so to the artists’ responses. First, the curators take us to the civic centre building in Ortisei, the Sala Trenka. Here, one large ground-floor space and a room to its rear have been prepared for an exhibition of 10 artists. These are probably the works that the maximum number of people will engage with during the four months of the biennale, so this is where the festival’s spirit and intentions must be most clearly articulated.

Sadly, in 2021, after they were selected, two of the artists on show here died: Etel Adnan and Jimmie Durham. In response, Pietroiusti declared a wish to dedicate the Biennale Gherdëina to their memory. The work of Durham, a poet, sculptor, activist for Native American rights, countercultural icon and winner of the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award at 2019’s Venice Biennale, features twice here, either side of the entrance. To the left, Une Blessure par Balle (2007) offers us a large, varnished slice of a tree, laid on one end, looking almost ready to be turned into a rustic table. However, museum-style, features from the tree’s “life story” are ringed and labelled: “a bullet from the second world war”, a “worm hole”, etc. Through its material, its imagined or real narrative, and through the presence of that worm, there are several resonances with the idea of “more than human beings”. This work is on loan from the collection of the contemporary art museum Museoin in the city of Bolzano, about an hour’s drive away, where a smaller, companion exhibition has been mounted on its ground floor – part of an undoubtedly necessary trail of teasers and incentives to encourage visitors to the biennale from across the region.

-installation-shot.jpg)

Jimmie Durham, Ghost in the Machine, 2005. Installation view. Image courtesy Biennale Gherdëina 8.

On the other side of the entrance stands another Durham work: a cast of an antique sculpture of the goddess Athena, strapped by a rope to a fridge (Ghost in the Machine, 2005). I suppose as a mythical figure, Athena is also a more than human being - tethered to domesticity is how I read it, but also perhaps conjuring implications around the way the fridge has become an object of worship, far more revered and idolised than our ancestral gods or myths.

Simone Fattal, Wounded Warrior, between two Etel Adnan works. Installation view. Image courtesy Biennale Gherdëina 8.

The Lebanese-born Adnan, creator of eloquently expressive films, books, poems, paintings and textiles, is represented by two of her customarily minimal landscapes, one with a sun rising, the other setting. These are placed in triangulation with Wounded Warrior (1999), a sculpture by Simone Fattal, a very poignant arrangement, given that Fattal is now mourning the loss of Adnan as her partner and champion. This figure expresses much of what Adnan movingly summarised, in a piece quoted in the catalogue: “When Simone Fattal faced her first chunk of clay, she did not hesitate. Her fingers, ie the deepest forces of her mind, made out of this muddy mass a person standing … She recreated in one stroke the first man of prehistoric times, and she created him standing. She created not an object but a surge, a movement, an essential movement, the one which separates the human species from the animal world, that is, at the same time, akin to him.”

Beyond Durham’s battle-scarred timber, are two large and colourful works by Martina Steckholzer. These were inspired by cave paintings, as well as ancient cosmologies of animals and references to astrological beings that ancient charts have imposed over the stars to represent astral bodies and constellations (in a kind of intellectual “colonisation of the stars”, as Ramos says). These two works dialogue with the two adjacent embroideries by Britta Marakatt-Labba, depicting celestial and earthly elements, symbols and diagrams, seemingly delineating a pathway to the heavens.

Marakatt-Labba’s family herded reindeer in northern Sweden, and she has lived as part of the Sami community, and with just the slant of her stitching and choice of thread she conjures up extraordinary textures – the pelt of animals, the silhouette of trees - a skill that comes as much from thousands of hours of embroidery practice as from the close looking and observation of the landscape and animals around her. The landscapes evoked in two further works nearby are also startling in the way they conjure a vivid sensation of place, plants and creatures: one with reindeer and a sledge surging across a white landscape, with a deep blue sky above them; the other featuring the shimmering branches of embroidered trees on a midnight-blue landscape and white sky.

Marakatt-Labba’s reindeer are good company for Judith Hopf’s concrete sheep, three of whom stand on a pink platform nearby. Part of her Flock of Sheep (2016) work, also from Bolzano’s Museion collection, their bulky, solid and yet endearing forms – with simple, sheep faces drawn in charcoal – were moulded from cardboard boxes as part of a protest at the wasteful quantities of packaging used by international retail giants. They are also a commentary on our sheep-like consumer behaviour as we and our purchases hurtle blithely around the globe, without a care for our impacts.

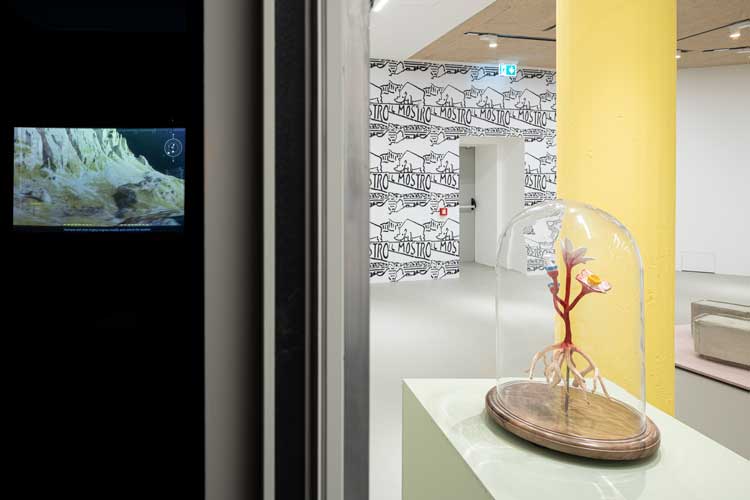

Giles Round, Il mostro, 2022. View at Hotel Ladinia, Ortisei. Commissioned by Biennale Gherdëina 8. Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo.

That corner is something of an animal enclave, if you include Giles Round’s Il Mostro wallpaper: this UK-based graphic artist has helped to define the typography and palette of the biennale’s posters, literature and exhibitions, using the valley’s signature colours of pale green, blue, pink and yellow. The wallpaper depicts a mythological animal he has imagined for the region, in the form of a rhino. It is plastered repeatedly across one wall and emerges in another installation down the hill, where Round imagines a whole souvenir industry in tribute to this mythical local beast, rendered in wooden toys typical of the local artisan industry, and displayed in a tribute to the rather wacky, folksy souvenir shopwindows nearby, under the brand Leonardo.

The installation in this room that has lingered longest and most hauntingly in my mind is that of Kyriaki Goni. The Mountain-Islands Shall Mourn Us Eternally (Data Garden Dolomites) (2022) is in three parts, comprising CGI animation, wooden sculpture and prints. A powerful speculative work, part fiction, part fact, for the CGI, Goni conjures up an “oracle”, from the regional plant Saxifraga depressa, which addresses the human audience on behalf of all species. Using graphs and simulations, it shows how global warming is forcing certain plants to retreat further and further up the mountain until – inevitably – they become extinct. It warns us that the same fate awaits us, while giving a fragile kind of hope (for rebellion, resistance or legacy?) by informing us of a decentralised alliance of “technoshamanic interspecies communities” that are being spread around the planet and preserving their digital memories in plant DNA, as “data gardens”. Embedding data in plant DNA sounds like pure fiction, but is, apparently, a current scientific research project. The calm, very empathetic English female voice of this oracle – entirely AI – spookily strikes just the right balance between fatalistic and sympathetic, articulating a feeling of alarm and mourning for a very plausible future. How can you mourn something you have not yet lost? There should be a word for that, as Pietroiusti says – and yes, I did Google it, but what came up, “anticipatory grief”, doesn’t nearly cover it.

The three silkscreen prints by Goni that stand outside the screening room were taken from drawings that informed her scripting and thinking process, but the curators insisted they be used in the display. The image of tall, craggy, very Dolomite-esque mountains leaning in to each other to mourn the loss of their human companions (as per the title) is an image I won’t easily forget. The wooden sculpture of Saxifraga depressa shown here, museum-style, under glass, was carved and painted with the help of one of the aforementioned local craftsmen – someone who normally paints religious scenes for churches and buildings. He used an unlikely mix of different paints and pigments, and told Goni he had never done anything so strange. Its otherworldliness is very much part of its appeal.

The final work in this room, The Quilt of All Beings (2022) created by Angelo Plessas, comprises an imaginary, sun-headed creature of many arms, multiple mythologies and species, but Plessas’s video work The Meditation on All Beings (2022), in a screening room further down the hill, is far more compelling, being hilarious and profound, silly and mesmerising in equal, trippy parts.

There is certainly a coherence and connection between all these works, despite a layering of narratives that could spin off in a multitude of directions, and the mixture of ethereal, conceptual, digital and esoteric works enriches the experience rather than diminishing it. Furthermore, the exhibition recruits our curiosity for further exploration. As for the works spread elsewhere, the choreography of their arrangement ensures serendipitous encounter, and the sites prove a trail worth following, though some works seem weirdly out of place. One such example is Karrabing Film Collective’s The Family and the Zombie (2021), which sits in a basement space off the high street, in the Hotel Ladina. It relates ancient stories of Antipodean colonisation, land appropriation and pollution that clearly have some thematic relevance to this setting, though its Australian wilderness location seems at odds. However, when we are told that one of their number (Elizabeth A Povinelli, the single non-indigenous Australian in the troupe, who plays the titular Zombie) hails from this region, its selection makes more sense.

Having set the tone with the initial exhibition, the biennale’s impact is enriched by encounters that bring us closer to the nature around us. There are two works in the Unesco world heritage site in Vallunga, where the startling beauty of the landscape can be appreciated free of roads, residential excavation and inhabitation. Here, Eduardo Navarro has conjured a most unlikely looking plant out of concrete (an unfortunate choice of material, really) and green paint. It has a door that enables you to enter the igloo-esque space at its base and listen “like the plants would listen” to the surroundings through the structure’s tall, flower-topped funnels. More intriguing and immersive – and infinitely lighter in their footprint – are Barbara Gamper’s textile banners. Gamper, a performance and textile artist, as well as a practitioner in somatic therapy (an alternative therapy that uses movement, breath and attention to unlock embodied patterns and traumas) these days prefers to hand over the physical performance to her audience. Three of her textiles are placed at different points around the landscape – one near a river, the other in the open, another by trees – and they carry specific instructions on things we can pay attention to, both outside and inside our bodies, which relate to different aspects of this space, and its botanical, geological and archaeological qualities. They are accompanied, via a QR code, by her SoundCloud meditations. The textiles, on unvarnished wooden poles, will fade and weather over the four months. Nothing about this is meant to be intrusive, though I love the idea that gentle, spontaneous, visitor performances will be a regular sight, as they lie down to commune with the earth or stroke and embrace the surrounding trees, as instructed by Gamper’s pre-recorded meditations.

There is an apparently captivating walk (which, sadly, I did not have time to experience), devised by Alex Cecchetti, which involves four trained guides (of whom Cecchetti is one), clad in specially designed costumes dyed with natural pigments, bringing visitors along specific mountain paths, drawing attention to the flora and fauna, visiting a yurt he has designed for the festival, and connecting with the elements.

Memory Garden Ritual, performance by Ignota. Opening of Biennale Gherdëina 8, 21 May 2022. Photo: Tiberio Sorvillo.

In another spectacular location, the Castel Gardena, an ancient and crumbling medieval structure overlooking the Fischburg valley, artworks percolate the semi-ruined courtyard and garden. There is an intriguing circular formation (Memory Garden, 2022, by Ignota) filled with the healing plants of the region, about which we are informed in a captivating little booklet (Seeds) which the same artists (Sarah Shin and Ben Vickers) have produced, offering up wisdom, healing rituals and recipes also working with cycles of the moon. Regular live performances are scheduled, for this and other pieces throughout the festival’s duration. Tucked into a courtyard staircase there is a brilliantly funny, but also wistful, animation by artist and musician Lina Lapelyte, whose narrative sees many of the wooden animals that populate the region’s souvenir shops shuffling off their shelves and out along the roads and streets, to finally break free in the meadows and mountains, accompanied by a wonderful chorus of humans imitating their baas, moos, bleats and cluckings.

Bruno Walpoth, Pinnochio at Castel Gardena. Image courtesy Biennale Gherdëina 8.

But most haunting of all is a pale, wooden figure of Pinocchio, made at human scale, and perched high in an alcove in the courtyard – like the religious figures that adorn its fading facade. It has two scorched and semi-destroyed feet. This is the work of the aforementioned local artist Bruno Walpoth, who feels his Pinocchio has something to tell us of this moment: “The Earth is on fire, and we are lying to ourselves.” Indeed.

By rights, work of this quality, in this setting, should provoke deep interrogations and could inspire long-term adjustments away from our less sustainable habits. But given its remote location, many visitors will have flown to visit the biennale, and will have to make further special journeys by car to see some of the most captivating works, none of which will be doing the environment any good. I am sure I won’t be the only one left with a lingering sense of enrichment laced with guilt. Now, surely there’s a word for that …