Stanley Whitney: Paintings. Installation view, Galerie Nordenhake, 2018. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin / Stockholm. Photograph: Gerhard Kassner.

Berlin, Germany

27-29 April 2018

by KRISTIAN VISTRUP MADSEN

“Please don’t tell me about any more young talented painters,” my young talented painter friend told me. “It really stresses me out.” It is true that once you start noticing, they are everywhere. And not just in those dusty blue-chip galleries where, in the seemingly interminable post-medium years, they tackily persisted in spinning cash from canvas. No, we are talking young dealers, chic dealers, project spaces and degree shows: painting is back, and Berlin’s Gallery Weekend proved a great opportunity to survey its return.

That is, if it ever truly went away. For while the past decade in contemporary art has been broadly defined by the hybrid forms of artists such as Camille Henrot, Ed Atkins and Hito Steyerl, at Frankfurt’s Städelschule, for instance, professors Michael Krebber and Monika Baer have continued their explorations of the boundaries of painting, and have continued, also, to influence the next generation. As the many shows of mature painters this weekend evidence, the surge of interest in this traditional medium among younger artists didn’t come out of nowhere – it has just been lying dormant while we rode out the various “post-”s.

Monika Baer. Barely titled (day), 2017/2018. Metal pigment, mineral pigments, acrylic, rigid foam on canvas, 230 x 190 cm (90 1/2 x 74 3/4 in). Courtesy the artist and Galerie Barbara Weiss, Berlin. Photograph: Gunther Lepkowski.

In Baer’s new exhibition Die Einholung at Galerie Barbara Weiss – as could be said for all of the German artist’s oeuvre – we witness painting’s struggle for legitimacy play out. Barely Titled (Day), 2017-8, a large canvas of abstract pastels, seems to have the colour of light itself. On the right side of the picture, a reddish whirl, and, on the left, a kaleidoscopic flicker, this work is almost entirely pret a manger, save for a bone of foam, an irritating glitch lining a contour at its centre. As ever in Baer (b1964, Freiburg), a small detail has derailed our consumption. In other works in the same suite that detail is a piece of fractured mirror, or a stucco droplet. In the series of yellow monochromes, it is the small metal device vying for the status of utility on the edge of the frame. In this way, Baer offers with one hand and deprives with the other, making for a body of work that consistently deepens as you come back to it. In Dachsmaske (2017), the wrinkled paper under the perfect pencil drawing, at first, is a point of contention, and since its most gratifying moment, its very reason. This is what distinguishes the sensual from the sexy: it takes time to get into it.

Stanley Whitney. Red, 2017. Oil on linen, 244 x 244 cm. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nordenhake Berlin / Stockholm. Photograph: Gerhard Kassner.

The stacked colour grids of Stanley Whitney (b1946, Philadelphia) at Galerie Nordenhake take no time to get into. More like a good pop song, Whitney’s paintings are as much about the initial appeal of the catchy hook as the relationship you develop with it over the years as you listen again and again. The work titled Red (2017), say, is obviously not just red, but what red would sound like as a song, and that song translated into a painterly composition; the feeling of red, red as refrain. Other titles are taken from musical lyrics: Western Wind from Bob Dylan’s Boots of Spanish Leather, Coney Island Baby from Lou Reed. And like the careers of these artists, Whitney’s spans five decades of sticking to his own tune, and sticking with his medium for better or worse. Music for your ears, these paintings, like the best evergreen anthems, are companions for life.

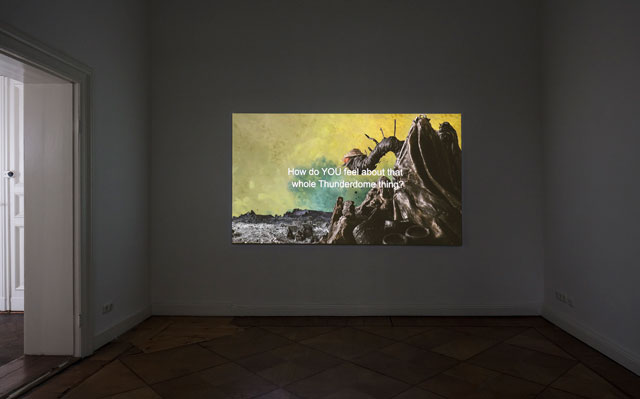

Peter Wächtler. Thunderdome has fallen, 2018. Exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and Lars Friedrich, Berlin. Photograph: Timo Ohler.

The exhibition by Peter Wächtler (b1979, Hanover) at Lars Friedrich’s gallery in Charlottenburg also has some of Reed and Dylan’s lonesome-traveller ethos. The centrepiece of Thunderdome Has Fallen is a stop-frame animation of a dragon in a straw hat flying over a Warhammer-esque landscape made out of plaster and chicken wire. Accompanying the winged creature is a poem relayed in deadpan sans serif across the screen, telling tales of missing the children (just a little) interspersed with continued references to the elusive “thunderdome”. More drunk dad in hotel bar than Lord of the Rings, however, Wächtler’s is a humorous portrait of the epic mundanity of life. Dramatic clouds exploding in the sky, an effect created by filming ink poured into an aquarium from below, aesthetically tie in a mesmerising series of paintings in the other room: hot-pink dolphins tumbling through fluorescent turquoise and petroleum hues. Their childish iconicity elegantly expands the sentiment of the video; the everyday as a sad and funny cocktail in beautiful colours.

Peter Wächtler. Untitled (cloud), 2018. HD-Video, 10:36 min. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Lars Friedrich, Berlin.

Painting as more than strictly a technique, but an attitude, as in Wächtler, a way of welding a certain type of depth or ambience beyond the canvas, was abundant also in a group exhibition curated by the artists Anna Lucia Nissen (b1985, Berlin) and Alex Rathbone (b1987, Middlesex, UK) inside their Schöneberg flat. Don’t Come In, as its title ironically advises, features a who’s who comprised mostly of recent Städelschule graduates and participants in the Berlin Program for Artists. In Emma Ilija Wyller’s (b1987, New York) engrossing painting in murky blues and smooth pink marble sculpture, the painterly logic of monochromatic abstraction is the impetus behind both works – in the end, riffs on modernist tastefulness that are themselves greatly enticing. In a work by Maximilian Kirmse (b1986, Berlin), a plastic portable toilet from a building site by the artist’s studio is elevated to a pointillist style, exemplifying the kind of dry humour that underscores the whole display. Nissen herself contributed a ceramic sculpture of a cigarette pack, decorated with the very recognisable mouth of the British PM Theresa May. The words “How do we do this???” are projected on to the sculpture, one in a row of absurd excerpts from May’s Brexit speech. But like the usual tobacco product death threats, on this spring day, her words fall on deaf ears.

Rochelle Goldberg. Installation view. Photograph: Kristian Vistrup Madsen.

In Moabit, the project space Éclair celebrated its first anniversary with Pétroleuse, an impressive show by the American sculptor Rochelle Goldberg (b1984, Vancouver). How fitting to end a painting roundup by an artist working so thoroughly within a different medium. Because Goldberg’s is really sculpture at a rare peak, her sensitivity to the relations between textures, objects and space impeccable. The exhibition takes as its starting point the punishment of a group of women falsely framed for arson in Paris in the early 19th century. Against this narrative frame, the backroom has been transformed into a miniature landscape of dimly lit herds of tuberous roots and orange peel cast in bronze, an atmosphere reminiscent of the abject fantasy world of the Polish master Alina Szapocznikow. By contrast, and in spite of Goldberg’s pedestrian choice of materials, the front space has a defiantly monumental feel: set on coffee-coloured carpeting, an army of ornamental glass bowls filled with water are caught, as if suffocating, under a thin sheet of sheer plastic weighed down with gold sequins. The gold mosaic wall is always here, I kept telling new visitors, but it has never looked as good as it does now.

On Sunday afternoon, after a marathon of about 20 exhibitions, I made sure there was no content on view at Trust, another project space with an academic digital culture bent, before I joined its sunset BBQ. Over grilled pineapple, a friend said to me that, while visually appealing, painting is the most difficult mode of art making to find words for. And as with that statement the weekend drew to a close, I made the decision – all matters of trend and questions of the waning or return of this or that medium aside – to indulge in my personal obsession. “On the contrary,” I replied, “I think painting begs for writing.”