Hélio Oiticica, installation view, Lisson Gallery, Bell Street, London, 26 April – 25 June 2022. © Estate of Hélio Oiticica; Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

by ALLIE BISWAS

As one of Brazil’s most trailblazing artists, Hélio Oiticica (1937-80) was already making radical contributions to the historic Rio de Janeiro-based Grupo Frente while still a teenager. Navigating modernist art through the lens of his Latin American origins, the sculptor and painter, whose practice also encompassed performance and writing, surpassed the minimalist tendencies of mid-century European abstraction with works that exuded the exuberance of his homeland. The initial gouache paintings exhibited by Oiticica in Grupo Frente’s first exhibition in 1954 soon evolved into compositions on paper that relied on printing techniques, presented at the collective’s subsequent showcase the following year. Ceaseless experimentation would continue to frame Oiticica’s approach for the next 25 years, resulting in a far-reaching body of work that maintained a lucid throughline.

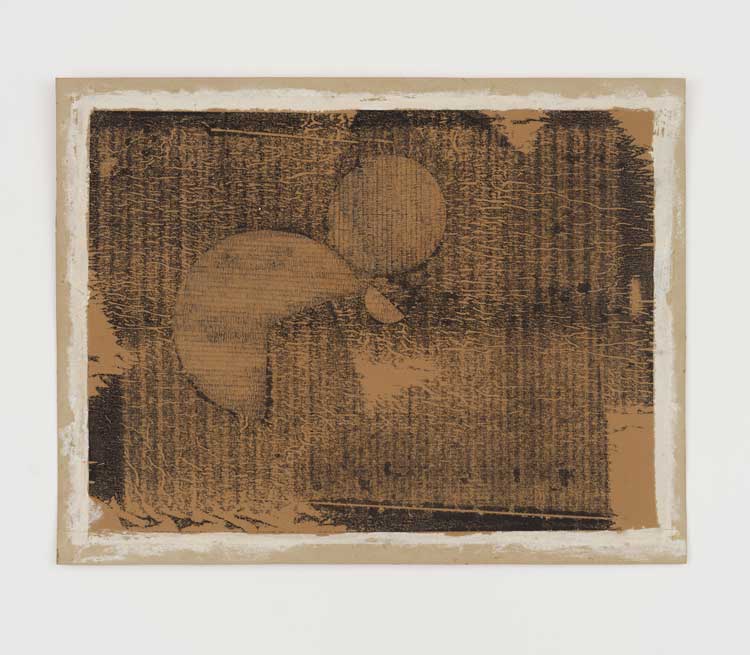

Hélio Oiticica. Untitled (Grupo Frente), 1955. Carbon print and gouache on paper, 25 x 32.6 cm (9 3/4 x 12 3/4 in). © Estate of Hélio Oiticica, Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

A selection of the artist’s works, covering the full expanse of his oeuvre, is currently on view at Lisson Gallery, marking the first Oiticica exhibition in London since Tate Modern’s 2007 show, Helio Oiticica: The Body of Colour. The curator Ann Gallagher, who organised both these exhibitions, spoke to Studio International ahead of the opening at the Lisson Gallery.

Allie Biswas: The exhibition offers a clear trajectory of Oiticica’s practice, including his first works, gouache-on-board paintings made in the early 1950s; the more streamlined Metaesquemas series of flatly painted shapes produced at the end of the 1950s, along with his Spatial Reliefs; followed by the Bólides that were created during the 1960s. The show culminates with a Penetrable made in 1979, the year before Oiticica’s death. Did you feel that an overview was important, given that Oiticica’s work hasn’t been shown in London for more than a decade?

Ann Gallagher: Hélio Oiticica: The Body of Colour, the exhibition that originated at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, was shown at Tate Modern in 2007. It was an extremely comprehensive survey of Oiticica’s work, although concentrated on the period up to 1970. Of course, since then, there have been several other museum surveys internationally that have covered both the range of the artist’s work and focused on particular aspects. This, in comparison, is a modest exhibition, but, yes, I was conscious that a new generation in London and the UK may not have seen any work by Oiticica, and that those who had seen the Tate Modern exhibition or individual works in other shows, may have been curious to experience works from the full span of his career.

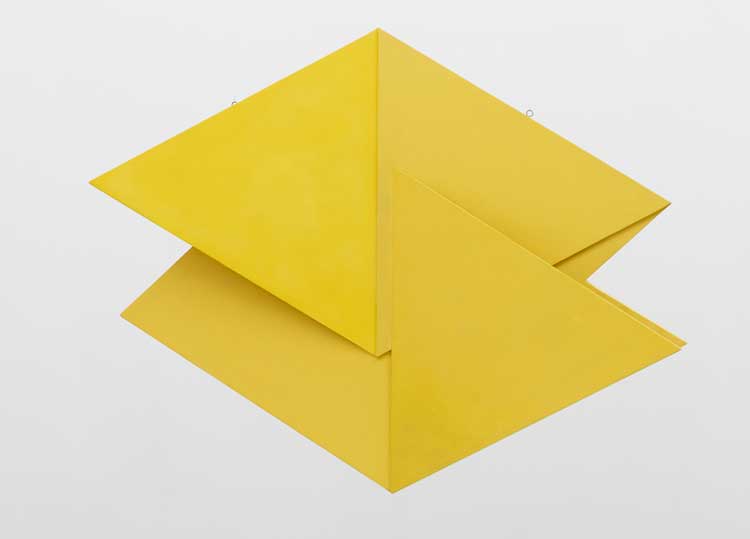

Hélio Oiticica. Relevo Espacial (Spatial Relief), 1959-60. Polyvinyl acetate resin on plywood, 98 x 120 x 25.5 cm (38 1/2 x 47 1/8 x 10 in). © Estate of Hélio Oiticica, Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

Space dictated that it was not possible to include film and other large-scale installations from the New York years (1970-78), nor any of the amazing public installations – such as the Magic Square series, conceived during that time – but it felt important to include works from the final years spent in Rio, when Oiticica continued to be extremely productive. We decided to include the film HO by Ivan Cardoso (1979), a film the artist was evidently very pleased with, since it enabled us to include Helio himself in the exhibition, as well as fellow artist Lygia Clark, and many other friends and fellow dancers. It also allowed us to introduce the sound, rhythm and movement that were such a vital aspect of the work.

Hélio Oiticica, installation view, Lisson Gallery, Bell Street, London, 26 April – 25 June 2022. © Estate of Hélio Oiticica; Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

AB: Oiticica first establishes himself as an artist after studying with Ivan Serpa at the Museum of Modern Art Rio, and, subsequently, associating with the influential Grupo Frente, which Serpa led, along with Mário Pedrosa and Ferreira Gullar. His work is included in the group’s second exhibition in 1955. Would it be right to understand Oiticica’s later affiliation with the Concrete movement, which had first developed in São Paulo, and then been adopted by artists in Rio, as a way for him to realise the objectives of his work? The Penetrables, begun in 1960, embody Oiticica’s idea of art as a lived experience; something to be activated by the viewer.

AG: Of course, Serpa clearly encouraged all forms of experimentation and individual thought. I think it would be fair to say that an evolution of concrete art was prevalent in Rio and São Paulo at this time, but with very different inflections. The fact that the Rio-based artists were less rigid in their adherence to the concretist principles, as defined by São Paulo-based artists (though this is, of course, an over-simplification of the range of opinions), and that these differences were theorised in texts by Gullar and Pedrosa, made it inevitable that a rupture would occur, and lead to the founding of the Rio-based neo-concrete movement. This advocated a less scientific, more phenomenological approach, and an independence of artistic creation “to express complex human realities”, as stated in the 1959 manifesto. This was very much in accord with Oiticica’s own thinking, and in a remarkably short period of time his work developed from two-dimensional painting into three dimensions – to the Nuclei that required active participation from the viewer – and culminated in environments that required immersion and interaction: the Penetrables from 1960.

Hélio Oiticica. B34 Bólide bacia 01 (B34 Basin Bólide 01), 1965-66. Plastic, earth, and rubber gloves, 15.3 x 63.7 x 40.8 cm (6 x 25 x 16 in). © Estate of Hélio Oiticica, Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

AB: The artist’s only retrospective in his lifetime took place at the Whitechapel Gallery, opening in February 1969, which he referred to as “the Whitechapel experiment”, and he remained in London throughout that year, also taking up an artist residency at the University of Sussex during this time. How do you think his experiences of living in England impacted on his work? Was he mixing with other artists here?

AG: In 1965, Oiticica’s work had been shown in Soundings Two at Signals Gallery (1964-66) and that same year he met Guy Brett and Paul Keeler of Signals at the 8th São Paulo Bienal. He was to have had a solo exhibition at this important London gallery, and after it closed, in 1966, it was due to Brett’s quiet but persistent advocacy that the exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery eventually took place. Although David Medalla was away at the time, Oiticica met members of the Exploding Galaxy shortly after his arrival in London in December 1968, including Jill Drower and Edward Pope. His time in London during “the Whitechapel experiment”, and also while in Brighton, seems to have been very important and fruitful for him. Although he had spoken of “the impossibility of experiences in galleries and museums” in this retrospective exhibition, he was able to incorporate many different bodies of older, recent and new work, showing them in relation to one another, in a mise en scène that became a project in itself, rather than a conventional survey exhibition. During this time, he continued to theorise much of his thinking, particularly on the concepts of “creleisure”and “subterraneo”,and from London he travelled to Paris, and to a symposium in California with Lygia Clark.

From his writings and letters, and documentation collected in the book Oiticica in London (2007), we can understand he made many friends. London would also have seemed an extremely free and exciting place at the time, particularly for artists and musicians, and especially in comparison with the growing intolerance and political oppression under the regime in Brazil by that time. Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil joined Oiticica in London in 1969, following their imprisonment and exile from Brazil.

Hélio Oiticica. B01 Bólide caixa 01, Cartesiano (B01 Box Bólide 01, Cartesian), 1963. Acrylic on wood, 32 x 21.2 x 20.7 cm (12 1/2 x 8 1/4 x 8 1/8 in). © Estate of Hélio Oiticica, Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

AB: Colour is a central component of Oiticica’s work. Does the function of colour change as his work develops from the two-dimensional “constructions” of the 50s, which were probably influenced by Piet Mondrian and Paul Klee, to the sculptural Bólides (1963-69), in which glass and wood vessels incorporate brightly coloured pigments or are painted in intense hues? Many of the Bólides served as memorials or homages to other artists, including Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, as well as to Oiticica’s father, who died in 1964.

AG: Colour remained a central component throughout Oiticica’s work. The research of the early years and the theories on colour he developed and articulated in his writings, particularly in the article Colour, Time and Structure [published in the newspaper Jornal do Brasil] in 1960, emphasised colour’s intrinsic relationship with light (especially white, yellow, orange and red), its manifestation as tonality, as well as its relationship with space, duration, movement and structure.

Hélio Oiticica. B04 Bólide caixa 04 ‘Romeu e Julieta’ (B04 Box Bólide 04 ‘Romeo and Juliet’), 1963. Oil with polyvinyl acetate emulsion on wood and plywood, 59.5 x 83.5 x 40 cm (23 3/8 x 32 3/4 x 15 3/4 in). © Estate of Hélio Oiticica, Courtesy Lisson Gallery

Beyond this, he went on to address nuclear colour in installations of multiple parts, and colour in relation to architecture in various larger-scale environments. He experimented with different textures, and with the Bolides he first introduced found objects and the incorporation of found materials, such as plastic containers, or existing pigments – for example those his father had used to make paintings, which he included in the Bolide he dedicated to his father after his death. Of course, his Homage to Mondrian Bolide makes obvious reference to the colour palette of the artist he so admired, as do other works dedicated to past and contemporary artists. Oiticica was always generous in his respect for, and praise of, other artists, both from recent history and his own near contemporaries.

Hélio Oiticica. PN 28 Penetrable, Nas Quebradas, 1979. Wood, brick, metal, nylon mesh, metal mesh, roof tile, plastic and jute, 357 x 450 x 310 cm (140 1/2 x 177 1/8 x 122 in). © Estate of Hélio Oiticica, Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

AB: The installation, Nas Quebradas (1979), forms the centrepiece of the exhibition. Did viewers of Oiticica’s Penetrable works, when they were initially exhibited (presumably in museums), physically engage with them as he had intended? Are the projects he developed for public spaces (executed or otherwise) the ultimate expression of his ideas relating to art as an act of participation?

AG: Nas Quebradas was first shown in the Espacio Galpão in São Paulo in 1979. Oiticica’s assistant on the project was Cecilia Ribeiro, whom he had met when she was assigned to assist him at Mitos Vadios (Stray Myths), a collective poetic event organised in 1978 by Ivaldo Granato, held as a form of protest against the first and last São Paulo Bienal of Latin American Art. As Cecilia kindly explained to me recently, Oiticica arrived in São Paulo with very detailed plans of the work, with very specific ideas for the materials to be used, including the particular yellow he wanted included, all of which they then had to source. That version of the work was destroyed after the exhibition, but those detailed plans have enabled future iterations to exist.

As for the more extensive architectural proposals, unrealised in the artist’s lifetime, the first I saw was in 2000, shortly after the unveiling of Magic Square 5 in the gardens of the Museu do Açude in Rio (recently restored), guided by the project’s curator, Marcio Doctors. I was absolutely stunned by it and all that it encompassed: the “suprasensorial”, the embodiment of colour, and an artwork inviting true social engagement. I have enjoyed experiencing the same reaction in friends and colleagues who encountered another version of the same work at Inhotim, in another wonderful setting. While every single body of work produced from Oiticica’s teenage years onwards was outstanding in terms of its radicality and invention at the time produced, the later Penetrables conceived for public spaces are indeed the ultimate expression of his ideas in that they fulfil his own prediction when he wrote: “Through the unity of architecture, sculpture and painting, a new plastic art’s reality will come forth.”

• Hélio Oiticica is at the Lisson Gallery, London, until 25 June 2022.