Honolulu Museum of Art

7 September 2017 – 21 January 2018

by LILLY WEI

The works of Philip Guston, Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still, among others, appear somewhat anomalous off the palm-planted courtyard of the Honolulu Museum of Art (HoMA). Although these masters of abstract expressionism seem ubiquitous, they are not often shown in Hawaii in full force. Even less often are they shown – if at all – in tandem with their Asian-American counterparts, several of whom lived and worked in New York in the movement’s heyday and beyond. They might easily have rubbed shoulders with each other at exhibitions and in the bars and cafes favoured by artists at a time when the art world was much smaller. This connection and its visual reverberations are what drives Abstract Expressionism: Looking East from the Far West, curated by Theresa Papanikolas, the museum’s recently appointed deputy director of art and programmes.

Franz Kline (American, 1910‒1962). Corinthian II, 1961. Oil on canvas. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Bequest of Caroline Wiess Law. © 2017 The Franz Kline Estate / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

It is a story that is more nuanced than has been acknowledged, and one that excited Papanikolas’s curiosity as she adds another intriguing chapter to the history of the New York School. This one, told from the perspective of the mid-Pacific, draws the greater part of its energy and appeal from its Asian-American artists, many of whom eventually returned to Hawaii. Quite a few are fervently admired local celebrities, but are not widely known elsewhere although they should be.

Satoru Abe (American, born 1926). The Idol, 1958. Welded copper and bronze. Honolulu Museum of Art, Gift of the Hawaii Community Foundation, Keiji Kawakami Art Foundation Fund, 1992. © 2017 Satoru Abe.

Two such stars are the sculptor Satoru Abe, who makes elaborate metal constructions in all sizes from a range of materials with the precision of a jeweller, and the painter Tadashi Sato, who progressed from architectonic or cubist-like compositions to more evanescent forms and the spiritual. His ethereal later paintings are awash with pale blues, greens and whites in a state of gentle flux, their lightness seeming to hover on the surface of the canvas. It is not a stretch to realise that they, and the other Hawaiian artists represented here, add credibility to the show for local audiences as much as the other way around. And for those who are not familiar with them and their work, there is the heady excitement of discovery.

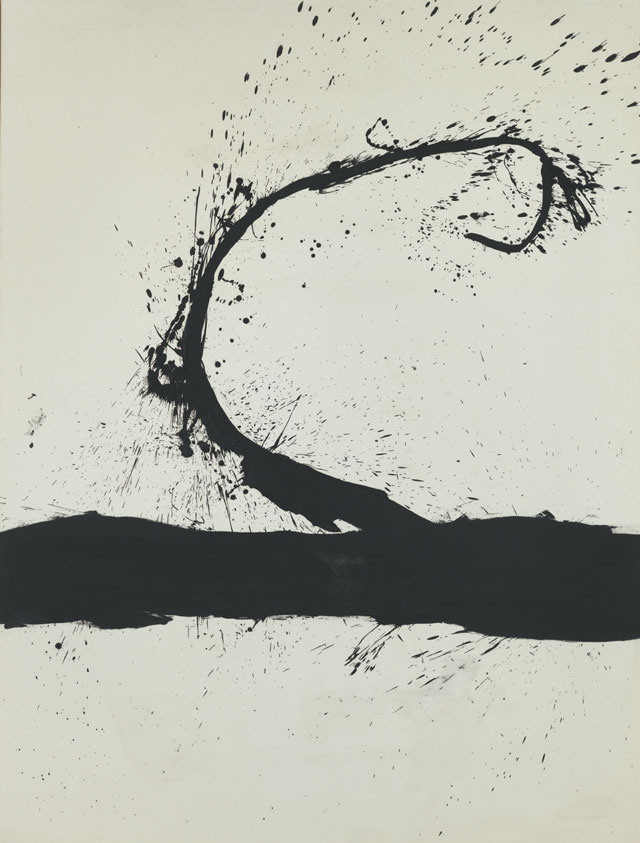

Robert Motherwell (American, 1915‒1991). Untitled, 1963. Oil on canvas. Honolulu Museum of Art, Gift of The Contemporary Museum, Honolulu, 2011, and purchased with funds given by Persis Corporation and gift of the Dedalus Foundation. Art © Dedalus Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Cannily chosen and installed by Papanikolas, the exhibition’s 45 works of art, which include paintings, sculptures and drawings, are a pleasure in terms of sheer numbers. They provide a comprehensive but not overwhelming introduction to the exhibition’s theme of abstract expressionism as an amalgam of east and west; here, each work carries weight and can be attended to. Presented as a dialogue between works rather than in chronological order, almost half of them are from the museum’s own collections, the majority dating from the 1950s and 60s. Just less than half of the 37 artists in the show are abstract expressionism’s A-listers (white, male and of European heritage), most of whom lived and worked in New York. Happily among them are two artists who are not quite as often included: Richard Pousette-Dart and Mark Tobey, both represented by strong works. Savage Rose (1951) is a roughly textured, saturated, colour-rich painting of insistently repeating bands by Pousette-Dart, who has attracted renewed interest lately. And from the museum’s holdings come two finely grained, “white writing”, monochrome drawings and a drawing of a faceted, vertical object that suggests coloured glass by Tobey, who was smitten by Asian aesthetics and philosophies, and is also the focus of renewed appreciation.

One standout from the Asian-American side is an exquisite, multi-lobed, woven mesh wire hanging sculpture from c1958 by Ruth Asawa, one of only three women in the show. (The role of women and women of colour is another long-overdue chapter in the abstract expressionist narrative that is currently being reexamined and expanded). Asawa, too, is beginning to receive her due after decades of neglect. Her recent, critically acclaimed solo at David Zwirner in New York was a knockout. The two works by Isamu Noguchi, the best known of the Asian-American artists here, are from the 60s, one a signature stone shape, in this case red travertine, and the other in cast bronze, both smaller works that respond to the pictorial images around them. It is of particular interest to compare Noguchi’s treatment of form and space with that of Asawa, who more fully integrates her sculptures with the space and is dependent on transparency and line. Noguchi, on the other hand, separates his sculpture from the space more emphatically, demarcating more clearly the boundary between solid and void. Another female artist is Tseng Yuho, also known as Betty Ecke (who died in September this year). Her collage is of extraordinary delicacy and shot through with glimmering flakes of cut gold, a technique common in traditional Chinese and Japanese art.

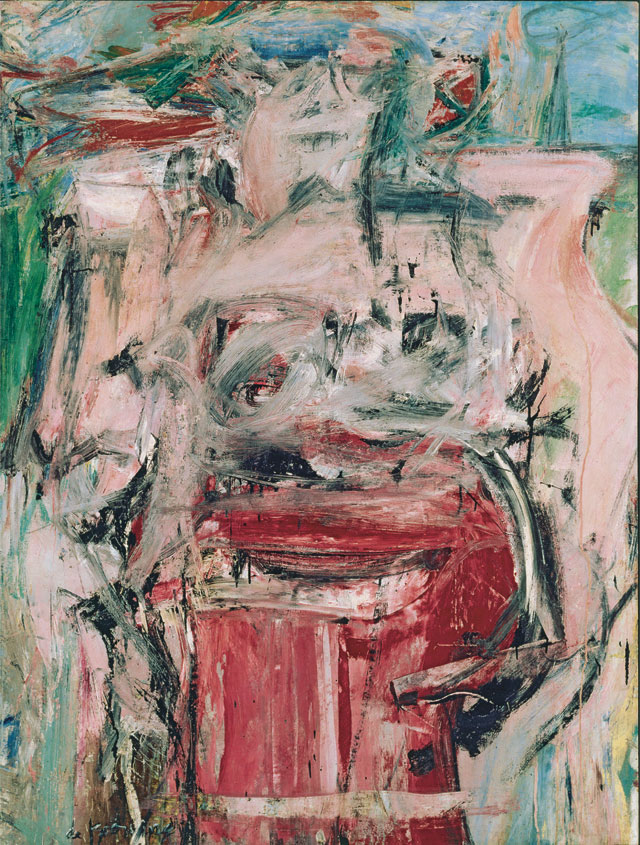

Willem de Kooning (American, 1904‒1997). Woman as Landscape, 1954‒5. Oil on canvas. Collection of Barney Ebsworth. © 2017 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Other artists base their work on the flex and momentum of calligraphic line, and it is a pleasure to compare that of Saburo Hasegawa to Guston’s in a 1963 ink drawing, or to the bold, painted signature slashes of Kline, or De Kooning’s forceful black swipes from Waves, a 1960 lithograph series. Morita Shiryū’s tumbling shapes seem related to Motherwell’s curled, flickered arc, which breaks away from its horizontal base like a wave beckoning ardent surfers. And Tetsuo Ochikubo’s All Things Exist, c1960-70, echoes Adolph Gottlieb’s Edge, 1972, while George Miyasaki’s lushly expressive brushwork is in sync with that of Pollock, de Kooning and a voluptuous pre-figurative Guston.

Some of the questions this juxtaposition inevitably encourages viewers to think about are: Who influences whom? Who is appropriating from whom? Are the Asian-American artists inspired by abstract expressionists, or are they drawn to the Asian elements of the style, in turn appropriated from Chinese, Japanese and other non-western art and culture, from calligraphy, Sung painting and Zen Buddhism, from John Cage and DT Suzuki, from the Gutai artists and Sung painting? And where does east become west and vice versa? When do peripheries become the new edge? When does Hawaii become its own centre in the Pacific, its gaze turned toward Asia as much, if not more, than to the mainland of the United States and towards Europe? Narratives proliferate as art becomes more global, more inclusive, more layered, and who gets to tell that story? Papanikolas gives us one intriguing recounting and it can be assumed that there will be many more to come, here and elsewhere.