VALIE EXPORT, 2019. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London | Paris | Salzburg. Photo: Ben Westoby.

by ANNA McNAY

VALIE EXPORT (b1940, Linz, Austria) is one of the most significant artists in the field of performance and new media, and has been awarded the 2019 Roswitha Haftmann Prize. Her career, which spans five decades, has been pioneering in film, video and installation art. However, she is probably best known for her groundbreaking Aktions and performances of the late 1960s and 1970s, which introduced a new radical form of feminist art to Europe.

In 1980, EXPORT represented Austria at the 39th Venice Biennale (alongside Maria Lassnig). For her first exhibition at London’s Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, this installation has been brought to the UK, and is every bit as powerful now as four decades ago.

Studio International spoke to EXPORT ahead of the opening of her exhibition.

Anna McNay: Your exhibition at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in London is a recreation of your installation for the 39th Venice Biennale in 1980, comprising 17 large-scale photographs mounted on wooden panels from your series, Body Configurations (1972-76), centred around the monumental sculpture, Geburtenbett (1980): a large, rusted copper bed, a looped video recording of a Catholic mass playing from a television monitor at the bed’s head, and a pair of detached female legs with a stream of red neon running from between them. Tell me a bit about the ideas behind the creation of this installation at the time. I presume it was created specifically for the Venice Biennale? What was your biggest hope in terms of reception of the work at the time? Was this achieved?

VALIE EXPORT: It is not a replica of the installation shown at the 39th Venice Biennale in 1980, it is the installation that was shown at the 39th Venice Biennale. At Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, the room is shown in the exact same way it was exhibited at the biennale.

It is not a large rusty copper bed either, but rusty construction steel. The bed part is made from blank structural steel profiles with industrial metal bed springs, covered with epoxy resin, which results in a wax-like surface; the female belly with spread legs consists of glass-fibre-reinforced synthetic resin. The neon tubes are made of red ruby glass.

VALIE EXPORT. Geburtenbett, 1980. Wedge, rusted steel structure. Bed: steel frame with bedsprings covered with polyester; Women's legs: fibreglass reinforced with synthetic resin;

Upholstery: stainless steel; Fluorescent tubes: red ruby glass. Video: sound, monitor, DVD, looped, 150 x 470 x 165 cm (59.06 x 185.04 x 64.96 in). © VALIE EXPORT/ Bildrecht 2019. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London | Paris | Salzburg. Photo: Ben Westoby.

The female abdomen and the spread legs grow out of the bed part, which has a wax-like surface. I had also thought about making a bed from wax – a wax mattress – but that would not have exposed the metal bed springs. Wax melts, too, and I wanted to preserve the character of the material.

The female legs are not actually detached as the belly and legs grow from the bed. The red ruby glass tubes symbolise the blood that flows from the female body.

The video shows a part of the Catholic Mass, namely Communion, in which, through the blessing of the host and the consecration of the wine, the body of Christ is metaphorically born. It is a divine birth, of Christ and the body of Jesus, in contrast to the birth of a human being, which is associated with the pain of the female body.

There is also a video on show, Remote, Remote (1973), in which I injure my fingers and I dip the bleeding fingers in milk, metaphorical for breast milk.

The installation is concerned with the representation of the female body in nature, in architecture through body configurations, and about the abstract representation of the female body on the birthing bed, with the bed as a symbol of both childbirth and of death. The host, which unlike the male body, can be “conceived” again and again by the priest in the Holy Mass, enters the human body through cannibalistic consumption.

The room at the biennale was created specifically for the biennale. I believe that the confrontation I wanted to express was achieved, even though, at that time, it was still very early on for dealing with such cultural confrontations.

AMc: You were educated in a convent until the age of 14. Do you still hold the Catholic faith, or has your work, in part, been a rebellion against this?

VE: I have no Catholic faith, I have left the Church. My artworks are still a rebellion against the Catholic faith.

AMc: Geburtenbett translates literally as Birthbed. So the idea of transubstantiation, or at least of creating life, is fitting. But presumably the identity-less female legs – those of the mother – have nothing to do with the Virgin Mary, but more to do with everywoman?

VE: Yes, the female abdomen with the legs, as I said before, has to do with every woman.

AMc: The red neon streak of blood must have been extremely provocative at the time, since female bodily fluids, especially blood (most especially menstrual blood) remain virtually taboo even today. You have said of your work that it is both aggressive and provocative: “My art was aggressive … aggression is provocation, and my viewers do not have to think like me, but they have to be provoked into forming their own opinions, their own reactions.” In what ways do you feel you were aggressive with your work?

VE: I certainly triggered aggressive responses through this work, because it does not have any mysterious pretence, but deals with the breaching of taboos. What you quote above is still valid for me. The more one tries to analyse the work of art, to reflect on it, the more one enters the work of art, attacks, and takes possession.

AMc: Do you think it is harder to be provocative in art today? Have artists lost the ability to shock?

VE: I don’t think so. We are all shocked by the conditions that prevail on our planet.

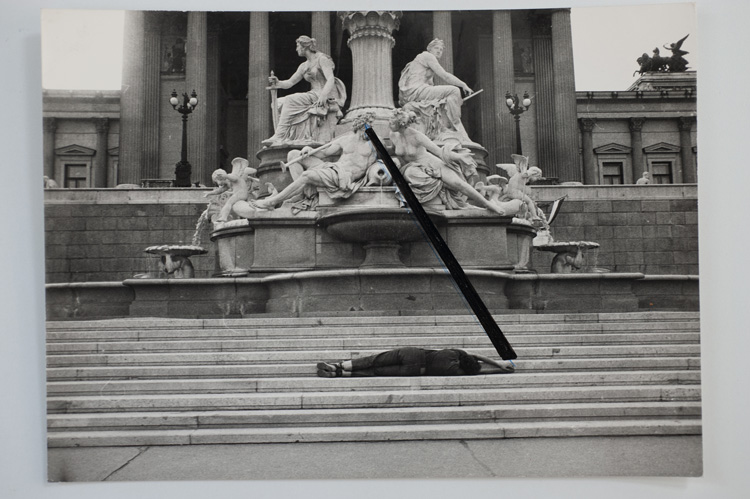

VALIE EXPORT. Starre Identität, 1972 / Print 1980. B/W silver gelatine print on baryta paper laid on chip board, 140 x 220 cm. © VALIE EXPORT/ Bildrecht 2019. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London | Paris | Salzburg. Photo: Ben Westoby.

AMc: Your Body Configurations images see you contort your body into shapes – triangles, rectangles, etc, marked with a black outline – and fold yourself along and around architectural structures. How did you go about producing these works? Did you work with someone behind the camera, or did you set it up to take yourself?

VE: I took the images of the body configurations partly by myself. For other configurations, I also had Polaroids taken by a photographer. We discussed them and determined the perspective and so on. These are also self-presentations.

AMc: Were all your photographs of a clothed body? What difference would it have made were they not?

VE: The bodies were all dressed. It was not my aim to show a naked female body in nature or architecture. It should be the everyday body in communication with the architecture.

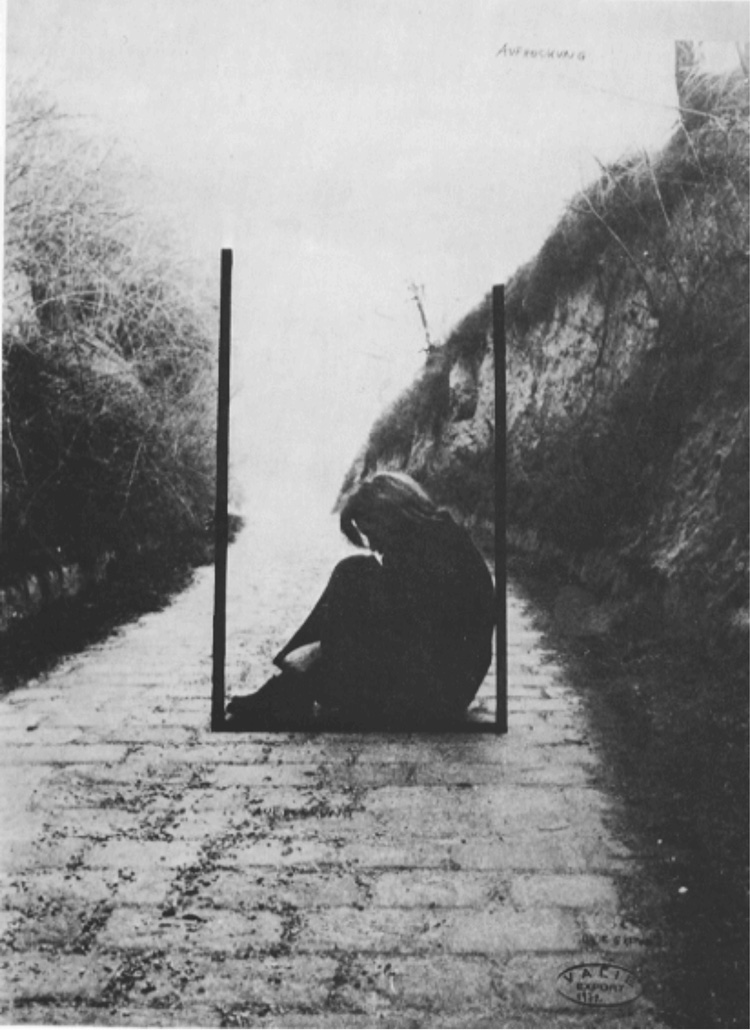

VALIE EXPORT. Aufhockung, 1972 / Print1980. B/W silver gelatine print on baryta paper laid on chip board, 230.5 x 170 cm. © VALIE EXPORT/ Bildrecht 2019. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London | Paris | Salzburg. Photo: Ben Westoby.

AMc: You have said that you associate architecture with the female body and set the architecture of the female body within the architecture of nature or the urban environment so that the body becomes an extension of the architecture. Do you draw a parallel between male power structures in urban architecture and the female spirit in nature?

VE: No.

AMc: How influenced were you by the land art movement that was taking place around the same time?

VE: I knew some land art works, but I was not influenced by them. Land art, arte povera, body art, conceptual art, etc all comprised the artistic expression of our time.

AMc: Do you believe we “build” our bodies in the form/shape/style we want them?

VE: No, I don’t believe that, because we don’t even know how we want our bodies to be. There are still so many unknown, unthought things, and for this reason we have so many different identities.

AMc: In a similar way, you “created” your own self as VALIE EXPORT, taking on a name of your choice, divorcing yourself from the patriarchal regime of passing on the father’s name …

VE: But I also wanted to expand and share my ideas …

AMc: While you have produced some works directly inflicting pain on yourself – for example, the short film Remote, Remote, mentioned above, in which you dig at your cuticles with a knife for 12 minutes, representing the damage inflicted on the female body that tries to maintain traditional beauty standards, you perhaps produced fewer such works than other feminist artists in the 70s, whose primary focus was the linking of the (female) body and pain – or even the (male) Viennese Aktionists. Do you not associate the (female) body with pain as much?

VE: I do also associate the female body with pain, but it’s not just about the body, it’s also about the female being, it’s about the psychological pain, etc.

Some time ago I received an invitation to take part in a competition for a memorial and commemoration site for Jewish victims of the Nazi regime in Austria 1938-45. I put a quote from Franz Kafka on my memorial: Das Einzig Reale ist der Schmerz (“The only real thing is the pain”).

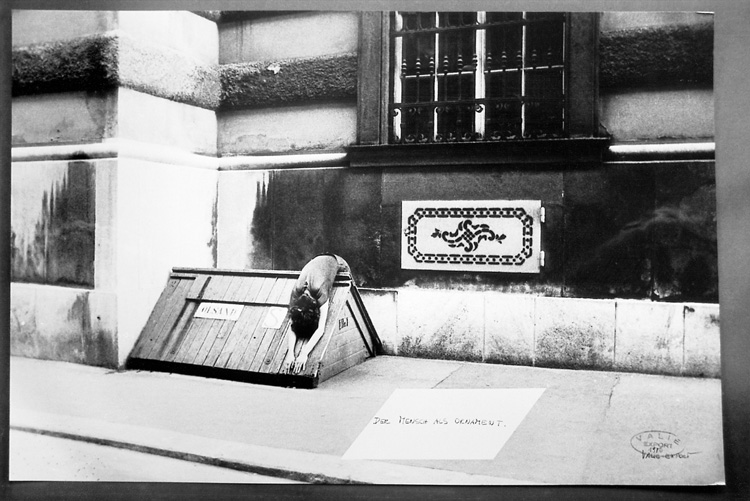

VALIE EXPORT. DER MENSCH ALS ORNAMENT, 1976 / Print 1980. Black and white silver gelatin print on baryta paper laid on chip board, 139 x 220 cm. © VALIE EXPORT/ Bildrecht 2019. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London | Paris | Salzburg. Photo: Ben Westoby.

AMc: An example where you put yourself at risk, and at the mercy of your audience, was Tapp und Tastkino (1968), where you walked the street with a small “cinema” with curtains around your naked upper body, and invited people to come and touch you. Tell me a little more about this work. Were you fearful of how people might respond? Was there a noticeable difference between the response of men and women?

VE: I didn’t put myself at risk with the performance and I wasn’t afraid. If anything, the visitors – namely the audience’s pairs of hands – were more afraid of “entering”’ the cinema. There was no difference between men, women and children. They could all enter the cinema for 33 seconds.

AMc: Perhaps your other best-known work is Aktionshose-Genitalpanik (1969) – so seminal that Marina Abramović selected it as one of her Seven Easy Pieces (2005). First, tell me about the making of this work, which has become legendary in its own right.

VE: I showed the performance Genitalpanik in a cinema. The photo series with the machine gun was created later.

AMc: Were you happy for Abramović to recreate the work? How different was the response to this recreation in 2005, in a museum setting, to your original Aktion in 1969? How do you understand this change in response?

VE: I gave Marina my approval to re-enact Aktionhose-Genitalpanik, but it makes a difference whether it is performed in public in 1969 or in a museum in 2005 – the social context is completely different.

VALIE EXPORT. ELONGATION, 1976 / Print 1980. B/W silver gelatine print on baryta paper laid on chip board, 82 x 56 cm. © VALIE EXPORT/ Bildrecht 2019. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London | Paris | Salzburg. Photo: Ben Westoby.

AMc: Certainly the setting must be key. You were always adamant that your Aktions were always performed outside of galleries and conventional art spaces. Was your desire to reach a wider and unprimed audience?

VE: Maybe.

AMc: What have you seen change over the past four decades in terms of feminist artists subverting and challenging the male gaze?

VE: When I have appeared naked in performances, I have noticed that the naked body is no longer viewed with such a voyeuristic gaze.

AMc: How much easier do you think it is to be a female artist today than when you set out?

VE: It’s easier, but still very difficult.

AMc: How difficult was it for you to become successful? What were some of the early way markers of your success?

VE: I once said that success is rocky. I think I was very analytical about my artistic expression right from the start.

AMc: At what point did you feel you had made it as an artist on the international stage? Was it difficult to be taken seriously for your art, rather than just for a woman causing outrage and provocation?

VE: I don’t know when that point was. There wasn’t a point as such. It depends whether you’re talking about my conceptual art, photography, performance, installations, or objects …

AMc: Finally, are you still making art today?

VE: Yes, of course. I am working on a big dome in which my video Würfelspiel (Dice Game) will play. It is a very intense video in high resolution – an exciting work with many possibilities.

• VALIE EXPORT: The 1980 Venice Biennale Works is at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, London, until 25 January 2020.