Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s–1970s, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, 11 February – 12 May 2024. Photo: Joshua White / JWPictures.com.

by JILL SPALDING

It’s not that Black artists have been remaindered. Henry Taylor just left the Whitney, the Harlem Renaissance has taken over the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Mark Bradford has won this year’s Getty Award. In Los Angeles alone this past year, Derrick Adams showed at Gagosian, Steve McQueen at Marian Goodman, Njideka Akunyili Crosby at David Zwirner, Mr Wash currently showing at Jeffrey Deitch and James Fuentes at Geoffrey Holder. Nonetheless, dealer talk of slowdown signals that buying fever has peaked, joining Black art to the more permanent rank of Established.

Streaking now on the long comet tail from Seoul to the US are the arts of Korea, newly distinguished in the US from “Asian art” by the flurry of gallery and museum shows exhibiting traditional and new work heretofore unfamiliar. Astonishing, in a world so connected, how little we still know about Korean art, its culture, or even of Seoul, held the world’s new style capital for its K-pop and fashion week, and for New York Philharmonic’s music director, Jaap van Zweden, lost to the Seoul Philharmonic because the “whole art scene in South Korea is exploding”.

Speaking to our inattention, even the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco’s landmark 1979 exhibition 5,000 Years of Korean Art – although it opened us to Korea’s early mastery of gold, jade, celadon, landscape painting, and such pioneering innovations as the hangul alphabet (still held the most scientific system of writing) and a metal printing machine that preceded Gutenberg’s by 200 years – failed to ignite lasting interest. Subsequent markers, such as Goryeo Dynasty: Korea’s Age of Enlightenment; Leaning Forward Looking Back: Eight Contemporary Artists from Korea; and In Grand Style: Celebrations in Korean Art during the Joseon Dynasty, rarely travelled and garnered few reviews. Incredibly, according to the Philadelphia Museum’s Hyunsoo Woo, until 1995 no US museum had held any major Korean work. Until 1999 even the Metropolitan Museum of Art had no assigned Korean gallery nor – until a decade later, when Eleanor Soo-ah Hyun transferred there from the British Museum – a designated curator. And the nation’s first Korean-born museum director, Min Jung Kim, came to the Saint Louis Art Museum less than three years ago.

.jpg)

Minjae Kim, Ghost chair, 2023. Stained and lacquered Douglas Fir, acrylic paint, 32 x 145½ x 15½ in.

Fast forward and seemingly overnight, it’s all things Korea. The out-of nowhere Korean Oscar-entry Parasite won for best foreign film, Squid Game went viral on Netflix, and renowned poet-essayist Cathy Park Hong has just given the prestigious Knight Foundation keynote address at Miami’s Institute of Contemporary Art. Lineages: Korean Art at the Met is running until 20 October; The Shape of Time: Korean Art After 1989 has just closed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; Perfectly Imperfect: Korean Buncheong Ceramics is showing now at the Denver Art Museum; at the Brooklyn Museum until 5 May is a collaborative brightly coloured clay fantasy by Do Ho Suh, who represented Korea at the 2001 Venice Biennale; the San Diego Museum of Art is showing Korea in Color: A Legacy of Auspicious Images until 3 March, and has just acquired a large work by next-gen artist Minjae Kim, whose recent solo show at Miami’s Nina Johnson gallery sold out.

,-2023.jpg)

Byron Kim, B.Q.O. 45 (Morning Burnoff), 2023. Acrylic on canvas mounted on panel, 82 x 60 in (208.3 x 152.4 cm). Image courtesy James Cohan.

Los Angeles, home to the nation’s largest Korean population, has long been attentive. Storied galleries such as Commonwealth and Council have nursed a roster of Korean-born artists to maturity – many, like Kimsooja, Yong Soon Min and Byron Kim have been touchpoints for local artists since the 1980s. Leaving, for the most part, such greats as Lee Bul and Lee Ufan to museums, younger galleries are taking up the new generation – a surprising number adept at conflating traditional and western sensibilities and techniques with a mix of ceramics, painting, sculpture, found materials, performance and video.

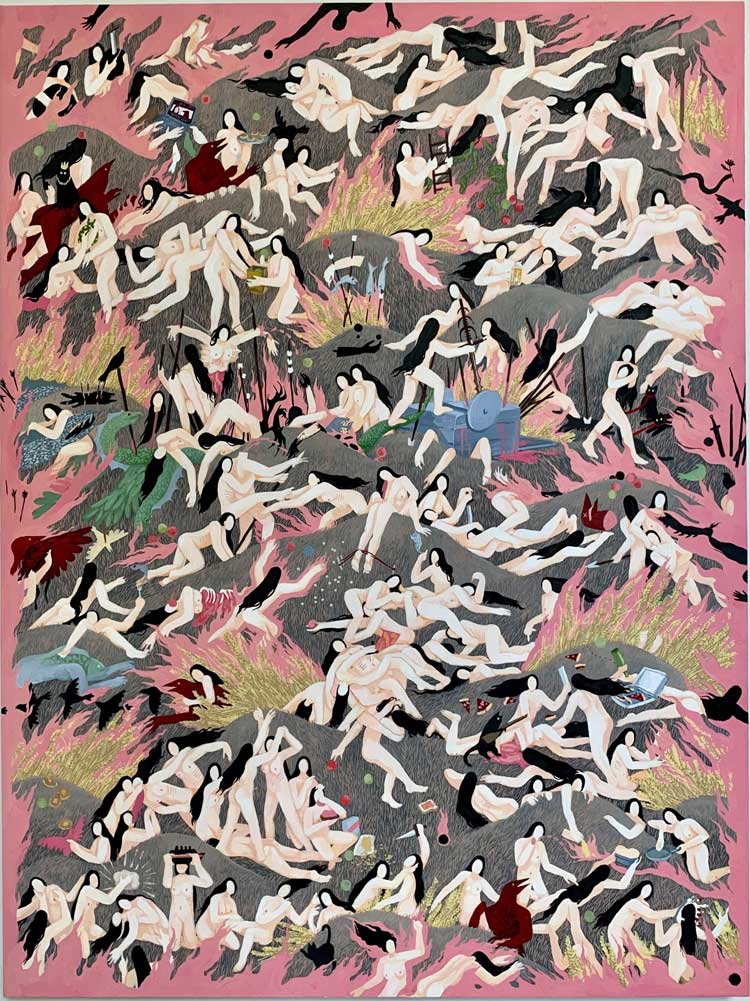

Kay Seohyung Lee, Fire, 2023. Gouache on birch panel, 30 x 40 in. Courtesy Yiwei Gallery.

Featured now at the Yiwei Gallery are large paintings by Kay Seohyung Lee, who is known for complex bodyscape explorations of her social, sexual and cultural identity, and surfaces built of unreliably organic materials (the one fashioned with sourdough collapsed). Also trending are Ken Gun Min’s colour-saturated, homoerotic, subversively cross-cultural depictions and, showing now at Albertz Benda, Sarah Lee’s eerie, imaginary landscapes composed of light, shadow and the stylised avatars of trees, hills, and lakes.

Sarah Lee, Among Trees, 2023. Oil on canvas, 50 x 52 in (127 x 132 cm). Image courtesy Albertz Benda.

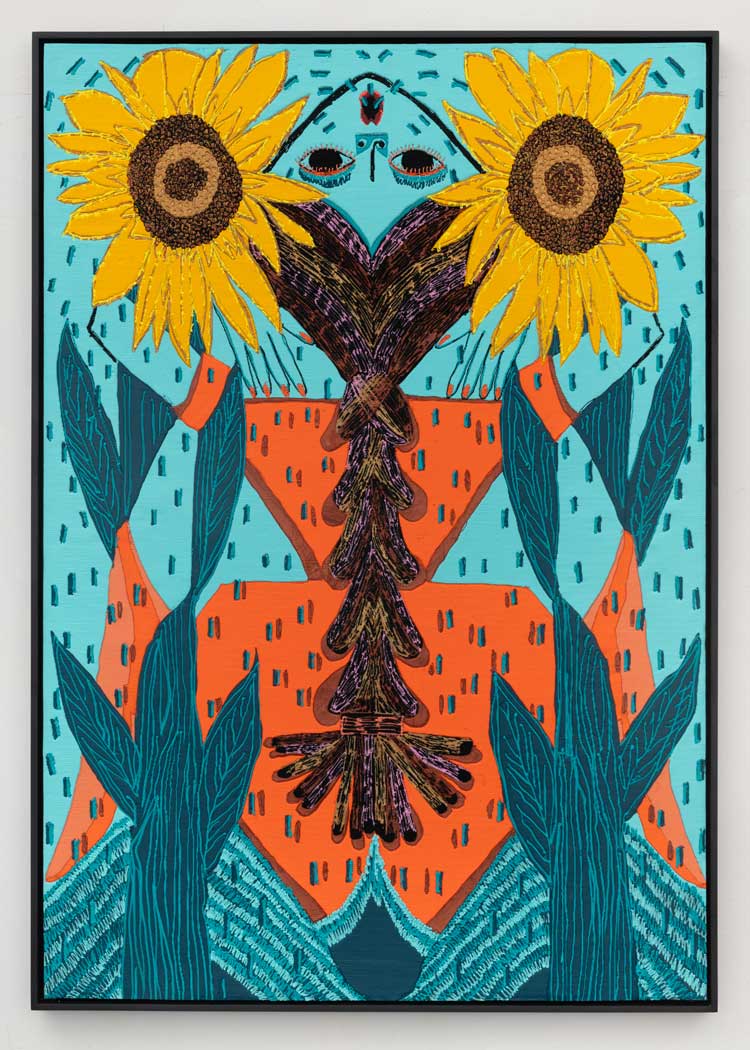

A must-view is the dazzling group of Summer Wheat’s 2023 collect-now vibrant paintings at Nazarian/Curcio: nothing derivative about those sunflowers (Fountain with Sunflowers) or those cubist ladies (Fountains) who could be from Avignon but that they negotiate water not stairs. Will you walk out with those stand-alone portraits of shoes swirled with bees? Or with Holes for its deft interplays between background and foreground, hollows and solids, fabric and flesh?

Summer Wheat, Fountain with Sunflowers, 2023. Acrylic paint and gouache on aluminum mesh, framed, 69 ¾ x 48 ¾ in (177.2 x 123.8 cm). Image courtesy the artist and Nazarian / Curcio.

Lingering longest in memory, Make Room follows a showing of Guimi You’s pleasantly out-of-focus landscapes with Youngmin Park’s luminous oil paintings – the medium, she says, that offers her the most options (“which types of oils, solvents, glues and what thickness of pigment”) to best express the formative human and animal iterations of her roleplay in the two vertical systems she experienced growing up in Korea. At once obligated and powerful, she was “the tail” of a hierarchical family dominated in descending order by her grandparents, parents, seven aunts and older siblings, and “the head” of their eight dogs, 15 cats and big carp – a bifurcation rendered on canvas with vivid entanglements of the two worlds, and resolved only by leaving Seoul for New York – a move that speaks for her generation of artists who find “Paris and London so old-school now”.

Youngmin Park, Closer, 2024, Oil on wood panel, 4 x 20 in (each panel is 4x4 in) Image courtesy the artist and Make Room, Los Angeles. Photo: Daniel Greer.

Those preferring to play it safe with mid-career artists are focusing on ceramicists Jennie Jieun Lee and Eun-Ha Paek; painters Yoo Geun-Taek, Sun Woo, Dabin Ahn, and Sinae Yoo; sculptors (in porcelain and soap respectively) Yun-Hee Toh and Meekyoung Shin; and multimedia artists Dew Kim, Kang Seung Lee, Young Joo Lee and Raejung Sim.

Speaking to Korean art’s commercial appeal, both Felix and Frieze LA 2024 art fairs did well with the tried-and-true and the young. At Lehman Maupin, wood totems by veteran sculptor Kim Yun Shin, who will be anchoring the Korean Pavilion at the forthcoming Venice Biennale.

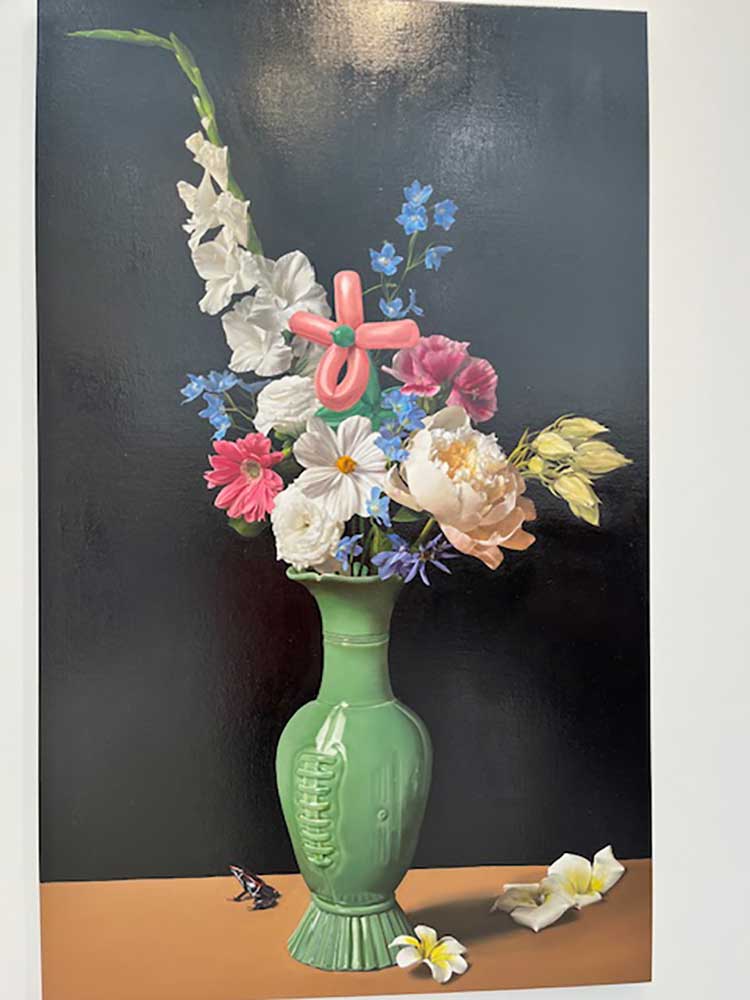

Kim Sung Yoon, Flowers in the Neo-Celladon Ball-Shaped Bottle, 2023. Oil on linen, 57.3 x 35.2 in (145.5 x 89.4 cm). Photo: Jill Spalding.

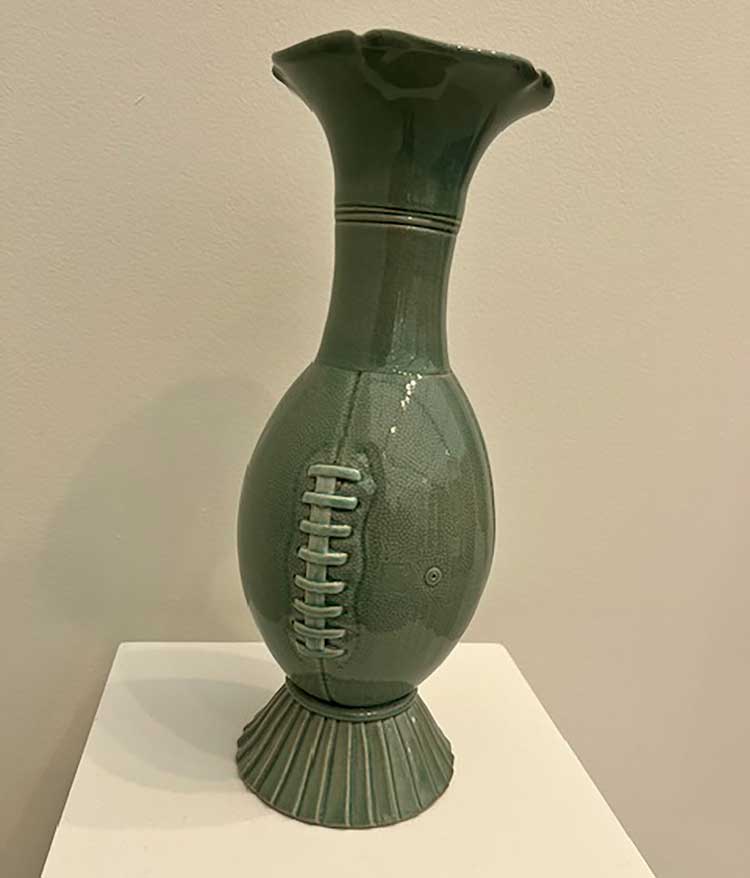

Yoo Eui Jeong, Neo-Celladon Ball-Shaped Bottle, 2020. Celadon, 15 x 5.9 dia in (38 x dia 15 cm). Photo: Jill Spalding.

At Hyundai, Kim Sung Yoon’s luminous flower paintings paired with their witty vases, by Yoo Eui Jeong. At Commonwealth and Council, an air-carving installation by Suki Seokyeong Kang (known for massive groupings of hinged, floated or stand-alone sculptures inspired by traditional forms such as Korea’s gridded musical notation) flanked Lotus L Kang’s visceral renderings of bio-disintegration (“metaphoric states of becoming and unfixity”) – four-metre-long suspended, light-prone emulsion paper “skins” and cast-aluminium mungo beans, cabbage, human cavities and membranes.

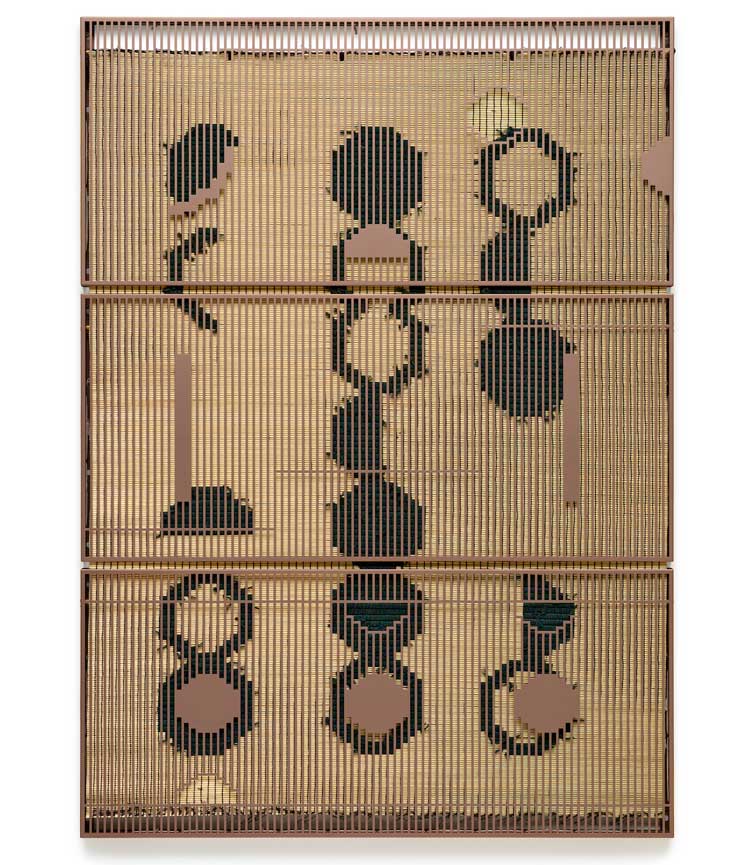

Suki Seokyeong Kang, Mat 120 × 165 #21-24, 2021. Painted steel, woven dyed Hwamunseok, thread, wood frame, brass bolts, leather scraps, 69 x 49.75 x 2 in (175 x 126 x 5 cm). Image courtesy Commonwealth and Council.

Lotus L. Kang. Molt (New York-Woodridge-Los Angeles-), 2022-24. Tanned and unfixed film (continually sensitive), spherical magnets, Approx 142 x 50 in (361 x 127 cm); approx. 112 x 50 in (85 x 127 cm); installation dimensions variable. Image courtesy Commonwealth and Council.

Although for the most part fresh and original, the work of these artists was not born sui generis. To better understand what informed it, head to Los Angeles County Museum of Art. First, browse the catalogue of its 2023 landmark exhibition, The Space Between: The Modern in Korean Art – an exposition of foreign influence on Korean artists between 1897 and 1965 – then visit its Korean gallery (the largest in the US). On view until 30 June is Korean Treasures from the Chester and Cameron Chang Collection, 35 objects that speak to high craftmanship and the influence of Buddhism and Confucianism. A primer of sorts, it serves as an introduction to contemporary Korean practice. More instructive is the museum’s wider collection. Learn here of the early mastery of form and line carried forth in so much of what is being done now. Find exquisite examples of sculpture and metalwork from the Silla kingdom’s gilded magnificence, the Paekche kingdom’s refined floral designs and jade carvings, the Goryeo dynasty’s unparalleled celadon (918-1392), and the Joseon dynasty’s misty landscape paintings (1392-1910) – all of which echo through latter-day work. Most impacting, South Korea’s defining art movement, Dansaekhwa, the aesthetic of monochrome minimalism – a deceptive simplicity born of freedom from Mongol occupation, seen as the missing link between the arts of China and Japan and a marking influence on succeeding generations.

Only with this grounding in Korea’s traditional arts can one fully appreciate the radical rupture documented by the top show in town, Only the Young: Experimental Art in Korea, 1960s-1970s, at the Hammer Museum until 12 May. A movement seemingly erupted out of nowhere, post-Korean-war “experimentalism” was developed as pushback against western modernism (post-impressionism, cubism, surrealism and fauvism) introduced from abroad by the end of Japanese occupation. Resolved to replace all the “isms”, seen as so-over, and to overthrow the entrenched art establishment, a group of self-named experimental artists and collectives, foremost among them the 38 shown here, created so-called “laboratory art” – a subversively messaged visual language that proved as revolutionary for Korean art as did abstract painting for western art. They walked chickens through flour, sandpapered cloth panels, formed drenched writing paper into balls of pulp, and dematerialised art with site-specific installations that presented nature as a medium.

How radical it must have seemed, this precipitous move to liberate artmaking from old tropes! To rethink sculpture, form and materials were denatured and given cryptic specificity. To destroy the structure of “picture”, traditional painting ceded to multidimensional surfaces and innovative uses of quotidian materials such as plastic and clay. Han Youngsup applied the “Korean-ness” of decorated architecture (dancheong) and concrete to abstract painting and Hyong-keun applied Korean minimalism. Moon Bokcheol brought Korea’s lost tradition of folk art to lowly items like gourds (once plentiful but now rare), which he painted and orbited on the canvas like planets. Lee Seung-taek reimagined the folding screen as sliced mulberry paper panels suspended from tree branches, and the urban skyline as a row of massive painted earthenware jars.

More ambitious were efforts to radically out-modern western modernity with a vision unique to Korea. Materials, portraiture, optics and assemblage would be completely rethought. Not all were successful. The striped geometrics of Suh Seung-Won’s oil painting Simultaneity 67-1 (1967), the serigraphs of Song Burnsoo’s Crayola-coloured Take Cover I, II, III, IV and V (1974), the wall-mounted neon columns of Kang Kukjin’s Visual Sense 1, II (1968), and the op art illusion manifested in Lee Seung Jio’s Nucleus F-G-999 (1970) were pioneered respectively by Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, Dan Flavin and Victor Vasarely. And although tying objects is a Korean tradition, even the great Kim Kulim’s 2021 tied Guggenheim too closely recalls (and not as homage) Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s revolutionary Wrapped Kunsthalle in Bern.

Lee Seung-taek, Torso, 1978. Photo: Jill Spalding.

More innovative were Sung Neung Kyung’s upside-down nonsensical maps; Choi Boonghyun’s life-sustaining IV tubing embedded in canvas, and Lee Seung-taek’s ceramics, stones and bronze torso, tied to transform an existing object “from a shape to a condition”.

More compelling still were the conceptualists (“experimental” a conceptual term as applied to practices that upended art as a fixed system), who engaged nature’s materials – wood, rock, fire, wind – to convey light, space and impermanence. Such was Lee Kun-Yong, whose struggle to free himself from “the tyranny of the future that stifles the present” manifests with a tree pulled up by its roots and entire fields burned to ashes. Shin Hakchul who, before launching the “people’s” movement (minjung), crafted nature – thorny branches wrapped with thread; a dead potted plant fixed to the canvas – to reveal life’s hidden meaning. And Lee Kang-So, whose elaborately staged videos of himself behind the glass he is painting on until we no longer see him question the relation of artist and viewer to art usually viewed frontally.

Boldest were the activists who, in the face of increasing repression, created art from discarded or found materials to denounce dislocation, poverty and war. Such are Nam Sanggyun’s framed cigarette butts and burnt matches and Lee Taehyun’s Command 1 (1967), its head a gasmask and body a backpack. Ha Chong-Hyun layered barbed wire over jute to denounce prison camps; Sung Neung Kyung framed excised sections of newspapers to call out censorship.

Ensuing military crackdowns on the political disruption of efforts “too avant garde to look like art” pushed art to “insanity”. Lee Seung-taek floated burning canvases downriver to flag neighbourhoods sacrificed to highways; Kang Kukjin and Jung Kungja dug their own graves and buried themselves up to the neck to accuse the establishment of killing them, and Kim Kulim drew attention to the burning of rice paddies and farmlands for pest control by cutting triangles into vast grasslands and torching the rest.

Most in-your-face were the “happenings” – spontaneous, often chaotic eruptions and performances billed as “doing art”, “anti-art” and “total art” – that were staged with whatever they could lay hands on, even the onlookers. Undertaken initially to out-rival those developed in New York, they were flamed by increasingly repressive regimes to render searingly visual the fallout of social inequity, incarceration, disappearance and death. As documents lined up on a wall they seem remote now but how brave were those efforts in the face of the escalating brutality.

,-1982.jpg)

Park Hyunki, Untitled (TV Stone Tower), 1982. Video, colour, silent, CRT monitor, stones. Dimensions variable. Guggenheim Abu Dhabi. © Park Hyunki. Photo courtesy of Guggenheim Abu Dhabi.

Most memorable are the stand-alone works freed from agenda by their timelessness. Foremost among them is Park Hyunki’s Untitled (TV Stone Tower) (1982), a brilliant riff on star artist Nam June Paik’s famed TVs-as-commodity that speaks to the experimentalists’ enduring influence.

A seminal show in that this revolutionary conclave of artists and collectives moved the needle of art history, Only the Young is essential viewing. Unless you are versed in what gave rise to them, it may not move the needle for you, but as an eye-filling lesson on what catapulted Korean art into the 21st century, it should not be missed. It is rare for a teaching show to be so visually gripping.