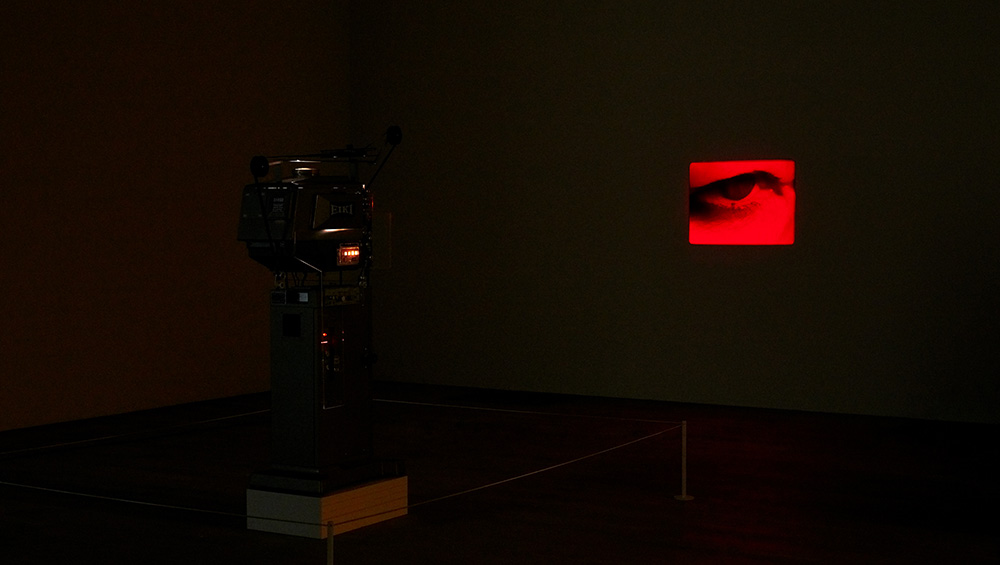

Steve McQueen, Charlotte, 2004, installation view, Tate Modern, 2020. © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery © Photo: Luke Walker.

Tate Modern, London

13 February – 11 May 2020

by BETH WILLIAMSON

The artist and film-maker Steve McQueen (b 1969) is known for his uncompromising vision of the world. Engaging with the social and political conditions of life, he does not shy away from difficult subjects or balk at unpalatable truths. Quite the opposite: “I’m interested in a truth, I cannot put a filter on life. It’s about not blinking,” says McQueen. It is inevitable that his films often do not make easy viewing, but that is the point.

This exhibition at Tate Modern focuses on McQueen’s work since 1999, the year he won the Turner Prize with film and video work. McQueen has also directed four feature films since 2008, including the award-winning 12 Years a Slave (2013). I really appreciated the openness of the layout of this exhibition with just 14 works spread out and with plenty of space to engage directly with each work.

Steve McQueen, Static, 2009, video still. © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery.

The vertiginous Static (2009) spins you until you are dizzy. It hits you immediately you enter the exhibition space as much with sound as with vision. The film is shot from a helicopter circling the Statue of Liberty in New York harbour, shortly after it reopened in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks. The sound of the helicopter blades is mesmerising and dominates the ambient sounds of other McQueen films being screened and the whirring of a projector close by. It is disorienting to have our viewpoint continually shifted, and the close quarters at which we see Liberty focuses our attention on the welded seams of metal and the green, oxidised copper surfaces.

While such materiality suggests permanence and stability, the continually shifting viewpoint, together with the timing in the wake of September 11, suggest otherwise. At times, however, the material figure of Liberty was a strong contrast for the two-dimensional diagrammatic body depicted across the gallery space in Once Upon a Time (2002).

Steve McQueen, Once Upon a Time 2002 and Static 2009, installation view, Tate Modern, 2020. © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery © Photo: Luke Walker.

The image here of a stylised human body showed skeleton, organs and venous system. This was one of a sequence of 116 slides originally used by Nasa to represent life on Earth. The series as a whole shows workers, childbirth, cities, nature and chemical formulae. This utopian vision fails to include any hint of disease, conflict or poverty.

In Charlotte (2004), we see a closeup of the eye of British actor Charlotte Rampling while McQueen’s finger moves around it, pulling at tender skin and briefly brushing the eyeball. Rampling’s eye adjusts and readjusts to the movement of McQueen’s finger, much as the camera lens adjusts and focuses. Bathed in red light, the scene is a meditation on the act of looking. It might also be considered as a reference to the eye-cutting scene in the Luis Buñuel film Un Chien Andalou (1929). However, the exhibition’s curator, Clara Kim, suggests that Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera (1929) might be a more apt comparator for Charlotte since both McQueen and Vertov are interested in “the sentient possibilities of the camera” in their respective films. Kim’s argument is a sound one and there is further evidence in McQueen’s Cold Breath (1999), where the closeup is on the artist’s own nipple, gently caressed then violently pulled – flesh as material.

Steve McQueen, Exodus, 1992-97, video still. © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery.

While this is not a chronological exhibition, it is bookended chronologically by Weight (2016) and Exodus (1992/97). In Exodus, McQueen’s earliest film, he tracks the progress of two men carrying palm trees through Brick Lane market in east London, sticking with his subjects despite the obvious difficulty of keeping them in view. Weight (2016) is a mesmerising sculpture. It was first shown at HM Prison Reading, where Oscar Wilde was imprisoned, as part of an exhibition recognising the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality in the United Kingdom. A gold-plated mosquito net is draped over a metal prison bed, creating a tension between the ideas of protection and confinement. The bare simplicity of the bed points to the naked vulnerability experienced in spaces of confinement while the exquisite sensitivity of the gold mosquito net gestures to the need for protection.

Steve McQueen. Ashes, 2002-2015, video still. © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery.

Ashes (2002-15) is perhaps the most poignant work in this exhibition. McQueen created the film as a tribute to a young fisherman called Ashes whom he first met and filmed in 2002. Years later, when he discovered Ashes had been killed, McQueen created this film by combining old and new footage. On one channel, Ashes is shown in his boat, smiling and progressing confidently towards the horizon and his future. The other channel shows his tombstone being built and his memorial plaque being etched. Meanwhile, two male voices are heard telling the story of Ashes’ death at the hands of drug dealers. There is an economy of means at play here as workmen quietly and calmly build Ashes’ tomb from concrete, then paint it white before adding the memorial plaque. The film is poetic, elegiac and calm in the face of a life cut short.

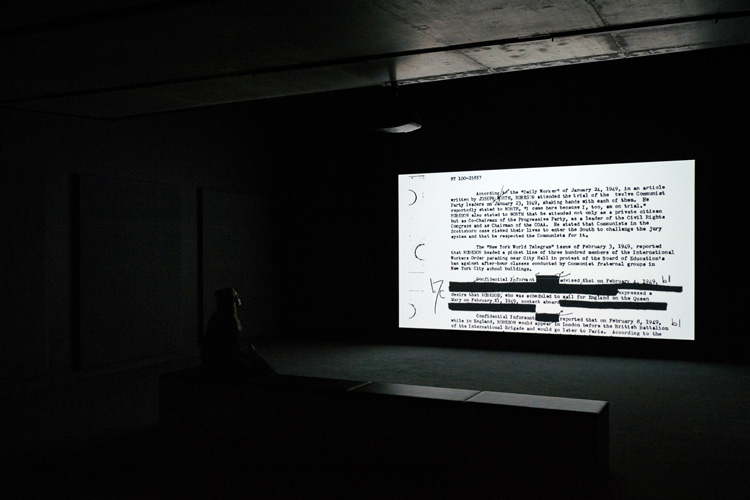

Steve McQueen, End Credits, 2012, installation view, Tate Modern, 2020. © Steve McQueen. Courtesy the artist, Thomas Dane Gallery and Marian Goodman Gallery © Photo: Luke Walker.

The longest work in the exhibition is End Credits (2012-ongoing). Dedicated to the African American actor, singer and civil rights activist Paul Robeson (1898-1976), the video of digitally scanned documents runs for more than five hours while the audio running time is an astonishing 42 hours (and growing as McQueen adds more documents). Robeson was put under surveillance by the FBI from 1941 and his work was blacklisted until two years after his death. Tens of thousands of documents from his FBI file (recently declassified), complete with annotated redactions, scroll through the image frame, much like the end credits of a film. Two voices read from the documents, but unsynchronised with what is shown on the screen. Even watching for 10 or 20 minutes will give you a strong sense of what Robeson was up against. As in all the films in this exhibition, McQueen’s attendance to his medium is key. In films that shake, stir and surprise, the camera always gets up close and personal in one way or another. I do not often have the patience for artist’s films, but this is an exhibition I will be revisiting.

• McQueen’s portrait of London through the format of the school class photograph, Steve McQueen: Year 3, is also on show at Tate Britain, until 3 May 2020.