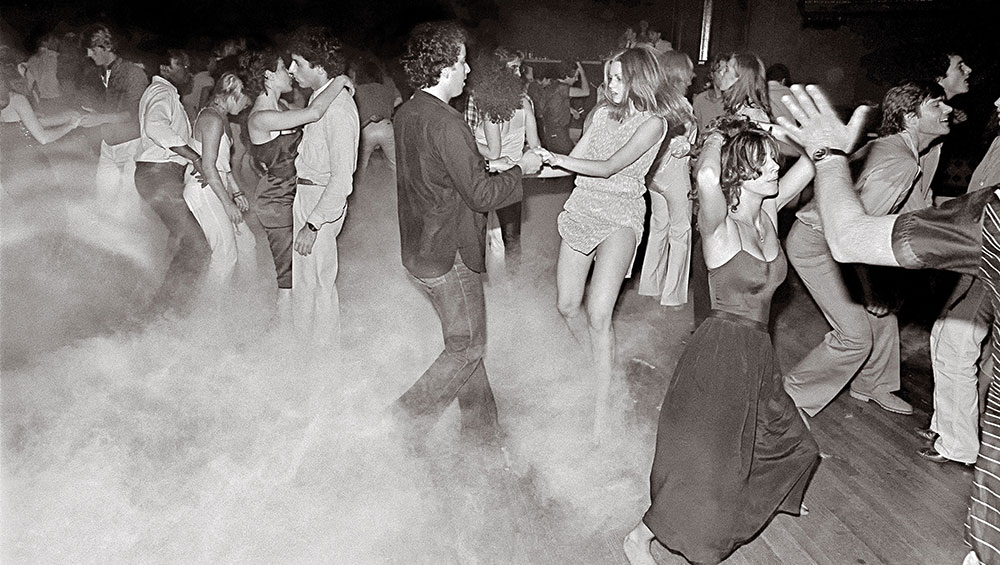

Bill Bernstein, dance floor at Xenon, New York, 1979. © Bill Bernstein / David Hill Gallery, London.

V&A Dundee

1 May 2021 – 9 January 2022

by CHRISTIANA SPENS

From lighting and performance to set, sound and interior design, and from the intersections and influences of art, music, fashion and film, Night Fever: Designing Club Culturereveals the ways in which this culture, or rather subculture, which is epitomised by its ephemerality and at times, secretiveness, is a unique part of society.

Featuring clubs from the 1960s onwards, in cities from Dundee to Beirut, and from New York to Manchester, Night Fever shows how these spaces nurture fringe communities through groundbreaking and experimental design, giving rise to creativity and kinship. Featuring clubs such as Manchester’s The Haçienda, Berlin’s Berghain, Detroit’s The Mothership, and Glasgow’s Sub Club, Night Fever also shows how culture has been formed in these experimental communal spaces, which are at once inclusive and exclusive, and the importance of seeing the artistic as well as hedonistic aspects of nightlife. In particular, through highlighting these particular venues, the exhibition demonstrates what these subcultures meant (and continue to mean) to communities and individuals whose identities, desires and visions don’t have other outlets or spaces in which to thrive.

Sub Club SoundSystem at BAaD (Barras Art and Design), Glasgow, summer 2019. Courtesy Brian Sweeney.

Developed in a collaboration with the Vitra Design Museum and the Design Museum, Brussels, Night Fever does an excellent job of showing how nightclubs are essentially ”designed experiences”, fusing many art forms to create a fleeting, immersive moment that is progressive and subversive, and so often an experimental, avant-garde space in which other creative projects are sparked and nurtured.

As Leonie Bell, the new Director of V&A Dundee, pointed out, the opening of Night Fever after a year of club closures gives a “deeper poignancy and meaning” to an exhibition that shows how “joyful, immersive, spectacular and emotional” club nights can be, and the implicit cultural loss we have experienced as a result of the pandemic.

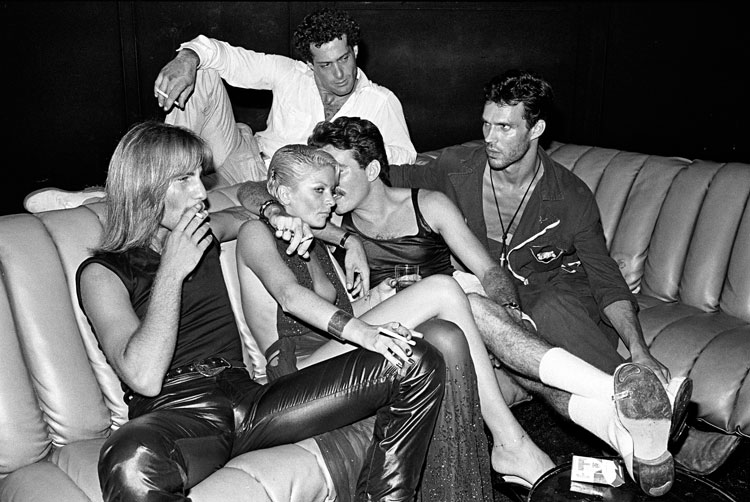

Guests in conversation on a sofa, Studio 54, New York, 1979. © Bill Bernstein, David Hill Gallery, London.

There is also a cautious optimism to this exhibition, however. As the chief curator at the Vitra Design Museum, Jochen Eisenbrand, said: “We find that there were other times of crisis after which nightlife experienced a real boom.” Noting how clubs have popped up in struggling cities and towns – giving examples of post-industrial spaces, or the “cracks of the urban fabric” after the fall of the Berlin wall – he said they have found abandoned buildings and “used them and repurposed them for something else”. There is a recuperative and transformative essence to the history of club design, the spirit of which is needed now more than ever.

Akoaki, Mobile DJ Booth, The Mothership Detroit, 2014. © Akoaki.

Beginning with the word FEVER in neon lights and proceeding chrono-thematically through the decades and their key themes, the exhibition explores myriad connected design influences and innovations, from the spatial building typology that emerged with Italian disco in the 1960s to the influence of film and comics that saw bars fashioned into spaceships and UFOs. Going through the 70s and 80s, and featuring clubs such as Studio 54 in New York, and Taboo and Blitz in London, the exhibition also features a red carpet with mannequins in dresses designed by Halston (who is the subject of a new biopic starring Ewan McGregor), one of the most celebrated designers to be associated with club culture at that time.

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture, mannequins wearing Halston dresses, 1970s, installation view, V&A Dundee. Photo: Michael McGurk.

It then explores the backlash sparked when this glamorous form of club culture became commercialised, and the emergence of more subversive spaces alongside collaborations with artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring and Leigh Bowery in the 80s and 90s. Eisenbrand said that clubs became “epicentres for experimentation … [their] ephemeral nature meant that you could try and then put away again”. He cites Area in New York: “They really staged a complete world there according to themes – temporary sets, for six weeks, which were then torn down again … These were times when things were not published on the internet, so there was more privacy.” This also meant, however, that these performances and designed worlds were truly fleeting, with no records left.

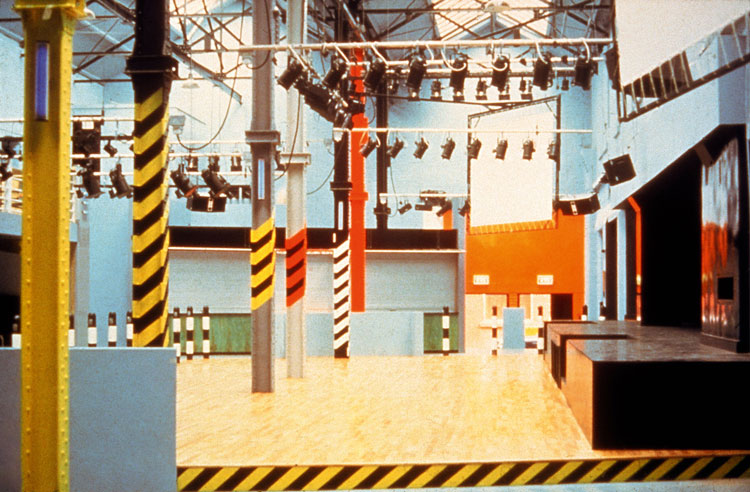

Interior view of Haçienda, Manchester. Courtesy of Ben Kelly.

One exception to this, however, was The Haçienda, open from 1982-97, from which a disco ball, bollards, and even part of the floor, were collected when it closed down. These objects and mementoes form a rare element of an immersive, at times archaeological, study of nightlife. These details of a lost time are displayed like religious artefacts, cultish and magical on that account.

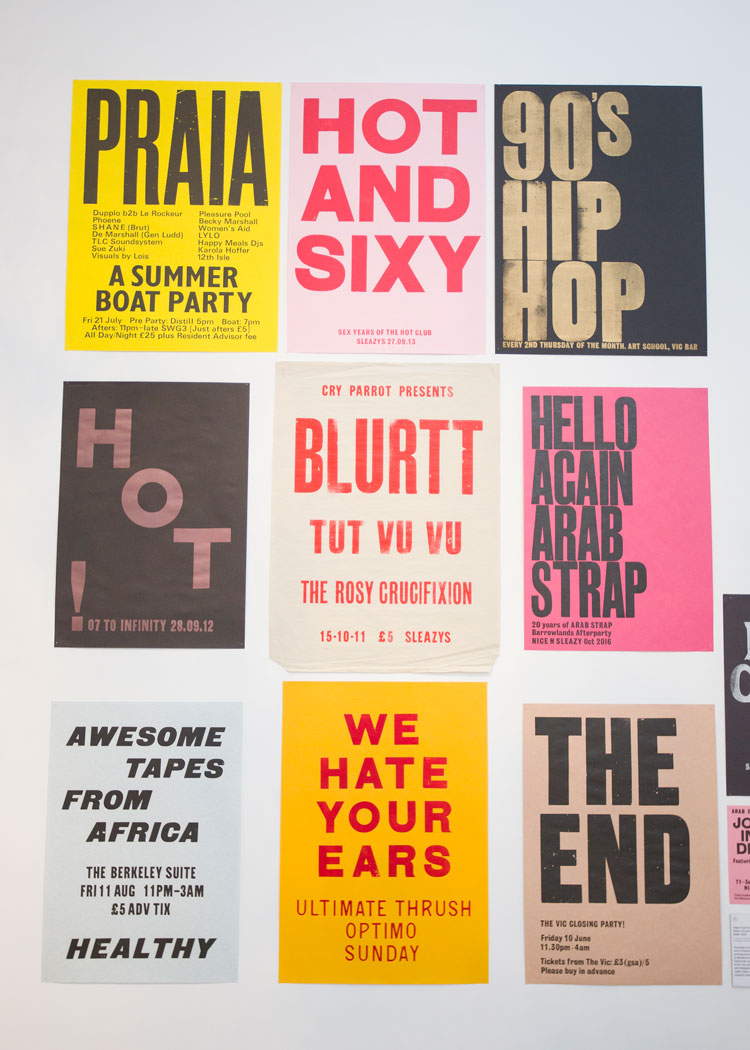

Scottish club posters by Edwin Pickstone, 2006–18. Courtesy of Edwin Pickstone / The Glasgow School of Art. Photo: Michael McGurk.

In the final section of the show, devoted to Scotland, there is a collage of photos and memorabilia – including posters, flyers, Polaroids, jackets, a tasselled tartan dress and handwritten notes – saved from legendary clubs such as the Sub Club and Optimo (Espacio) in Glasgow, Club 69 in Paisley, Fever in Aberdeen, and Rhumba Club (which existed in multiple forms and locations). Showing the distinctly Scottish subculture that emerged in the 90s particularly, this section also reveals the crucial links between the musicians and designers in Scotland and those in Chicago, Detroit and Europe, at that time. Epitomising a DIY attitude, and real kinship, as well as an international outlook and artistic awareness, the Scottish section shows, as the show’s curator, Kirsty Hassard, said, that clubs are “cultural venues as well as design venues”, providing key opportunities for people to access the arts in a grassroots, subversive and communal way.

Night Fever: Designing Club Culture, installation view, Scottish club culture section, newly curated by V&A Dundee and Mairi MacKenzie of Glasgow School of Art. Photo: Michael McGurk.

At a time when, in Dundee especially, several local clubs, such as the Reading Rooms and Underworld Café, shut down even before the pandemic, this part of the exhibition is a tribute to the real cultural significance of these institutions, putting them in a wider international, artistic context, but never forgetting the personal, intimate roots. Screening Tim Knights’ film, Hold Me, which montages crowd-sourced footage to capture moments in Scotland’s club history, this final chapter underlines the nostalgia and social significance of club culture, which, for so many, is a way of life and love as much as it is a gateway to a lifetime engagement with many forms of art and design. With clubs globally at a tipping point, Night Fever brings this creative industry out into the light, revealing spaces of innovation, experimentation and creative freedom that will be crucial to our society’s resurgence, recovery, artistic freedom and happiness in years to come.