Michael Takeo Magruder with Drew Baker (3D visualisation & programming), Imaginary Cities — NYC (11062471656), 2019. Real-time virtual environment (Unity3D) with soundscape (Flash), infinite duration. Photo: David Steele © Michael Takeo Magruder.

British Library, London

5 April – 14 July 2019

by JOE LLOYD

The library is an institution in flux. From time immemorial, libraries have served as repositories of that which has been written and recorded, stored in material form. As digital media has created new ways of conceiving an archive, queries have arisen as to how a library can best seize on, and adapt to, these shifts. For the British Library, which contains the vast accumulated holdings of a nation, there is an additional question: how to present such changes to the public?

Enter Michael Takeo Magruder (b1974), an artist who uses digital technologies to create works shaped by data, and his exhibition Imaginary Cities. Born in the US but now based in the UK, Magruder studied biological science, and his output has a scientist’s interest in processes and systems. Since turning to art in the late 1990s, he has featured in about 280 exhibitions including, Manifesta 8 in Murcia. Magruder’s most recent work has tended towards weighty themes, including family separation at the US-Mexico border and the travails of refugees from the Syrian war.

Michael Takeo Magruder, detail of Imaginary Cities — Paris (11097701034), 2019. Algorithmically generated mono prints on 23ct gold-gilded board. Photo: David Steele © Michael Takeo Magruder.

For the British Library, he has created four new pieces in response to the library’s digitalisation schemes. In 2013, the library’s new Labs department digitalised 65,000 19th-century books, before using a custom programme to extract maps, illustrations and photographs. These were then placed on a Flickr Commons account called 1 Million Images from Scanned Books (which is exactly what it sounds like), an enormous, enthralling collection of material.

Magruder’s project takes as its starting point four maps from this resource. He initially wished to present cities from across the world, but finally settled on four western metropoles, because of their relatively comprehensive level of detail. Readers have always left remnants on texts and images: marginal notes, accidental tears, skin cells. With digital matter, a different sort of trace survives. “When an archive becomes digital and is opened to the world,” Magruder says, “it becomes a ‘living’ structure that is constantly changing as people connect to it, use it and leave traces of themselves.” He then monitored the metadata – user interactions, such as page views, zooming in, favouriting and tagging – around these images, and used it to create an artwork for each. Echoing the British Library’s bridging of the material and the digital, all the works use traditional craft techniques, such as woodwork and gilding, alongside VR simulation and algorithmic design.

Installation view of Michael Takeo Magruder, Imaginery Cities at the British Library. Photo: David Steele © Michael Takeo Magruder.

The four chosen maps, displayed in a vitrine, are fascinating things with which to get acquainted. There is London in 1834, still easily recognisable today, as it sprawls into newly built suburbs to the north and south. The Paris of 1872 is, unsurprisingly, even closer to the 21st-century city, with the medieval quarters cut through by Baron Haussmann’s relentless boulevards; newly built squares create orderly lacunas in the capital’s closely clustered streets. The two American maps are more startling. New York City, depicted in 1766-67, but published later, is still a fledgling outpost at the tip of Manhattan, a pocket of conurbation that quickly gives way to farmland. And Chicago in 1874, three years after its cataclysmic fire, is depicted not by built structures but through the relentlessly gridded pattern of its roads, which to these European eyes seem almost too rigidly regular to be navigable.

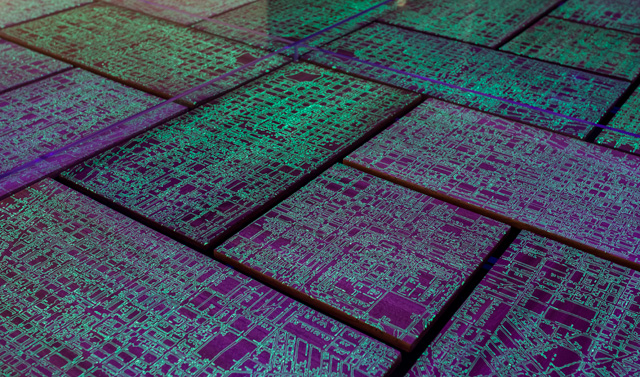

Michael Takeo Magruder, detail of Imaginary Cities — Chicago (11107522893), 2019. Laser-engraved spate hardwood with UV light-reactive inlay. Photo: David Steele © Michael Takeo Magruder.

Magruder’s responses to these maps – or rather his responses to users’ responses to these maps – are varied in material and techniques. Chicago is transformed into a “physical data structure” composed of 20 wooden panels, arranged together like a jigsaw puzzle. Magruder has used the online map’s metadata to create a complicated, circuit board-like web of vectors, extending apparently infinitely. Bathed in UV light, these lines glow with a sickly lichen green. The city both thrusts out expansively and appears to moulder. The wooden boards, an element taken from traditional craft, has something of a grounding effect on this otherwise eerie work. Magruder’s take on Paris, meanwhile, is tantalisingly otherworldly. The French capital is represented by four glimmering monoprints, set on gilded cotton board. Generated by algorithms, they turn the City of Light into a series of symmetrical kaleidoscope images, pivoting out from a central point. Repeated localities – the green lung of the Champ de Mars, for instance – becomes akin to a reoccurring motif on an abstract painting..

While Chicago and Paris are represented in static pieces, London and New York play with temporal shifts in metadata. The former comprises a triptych of LEDs in silver-gilded frames, as well as a murky algorithm-created sound piece. Each screen shows greyscale fragments of late Georgian London distorted and layered on each other to form a chaotic mulch, which continuously shifts, based on user interaction data from the entirety of 2018. It turns the city into a punishing, repressive labyrinth; I’m reminded of William Cobbett’s phrase The Great Wen, which referred to London as a cyst-like swelling, or William Blake’s “charter’d streets” and “blackning church[s]”.

Installation view of Michael Takeo Magruder, Imaginery Cities at the British Library. Photo: David Steele © Michael Takeo Magruder.

Magruder also grants New York a sinister aspect, with a large-scale video and virtual reality work, newly rendered each day based on the online map’s server application. It glides you through and above the streets of a dystopian plane of stripped-down Empire State buildings, over the course of a day-night cycle. It’s the most developed piece in terms of technology, but aesthetically the least compelling, lacking the visual intricacy of the other three or a clear connection to the fledgling New York in the source map.

Several discrete elements have been interwoven to create these artworks: historical urban maps, interaction data from their digitalisation, craft processes and various technologies. This tangle of parts, as well as the gaps in one’s understanding of just how Magruder applied his data to arrive at particular works, somewhat muffles the exhibition’s voice. Why is London so grey and Chicago illuminated by UV light? What does the Rorschach inkblot-like Paris say about the city? But Imaginary Cities is not really an exhibition about the cities themselves, nor is it entirely about the final outcome. It is about the way something as seemingly intangible as online metadata can be harnessed into a physical artwork, and it is about the artistic possibilities that data offers for the archive. And on these points, Imaginary Cities is crystal clear.